This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Surveillance of Ethiopian Women Athletes for Capital

Tracking Work from the Wrist: The Surveillance of Ethiopian Women Athletes for Capital Hannah Borenstein Duke University [email protected] Abstract This essay explores the proliferating uses of GPS watches among women athletes in Ethiopia. Aspiring and successful long-distance runners have been using GPS watches in increasing numbers over the past several years, rendering their training trackable for themselves, partners, coaches, sponsors, and agents located in the Global North. This essay explores how the transnational dimensions of the athletics industry renders their training data profitable to systems of capitalist accumulation while exploring how athletes put the emerging technologies to work to aid in their pursuit of succeeding in the sport and work of running. New Metrics In 2013, when I was first living with young sub-elite athletes at a training camp in Ethiopia, nearly all runners wore basic digital watches. Casio was the leading brand, but any watch that had a time setting, a few alarms, and, crucially, the start-stop function, was a critical instrument for long-distance running aspirants. Watches that could record splits—different intervals of training—were coveted, but by no means the norm. Thus, the metric that everyone used to discuss training was time. Recovery runs were spoken about in terms of hours run: “one- Borenstein, Hannah. 2021. “Tracking Work from the Wrist: Surveillance of Ethiopian Women Athletes for Capital.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 7 (1): 1–20. http://www.catalystjournal.org | ISSN: 2380-3312 © Hannah Borenstein, 2021 | Licensed to the Catalyst Project under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license Special Section: Self-Tracking, Embodied Differences, and the Politics and Ethics of Health twenty.” Speed sessions were broken down into minutes: “we did three minutes by eight with sixty seconds rest.” Athletes knew that this would need to be converted to kilometers for their performances, but conversations about training were discussed in terms of time. -

Kanhaiya Kumar Singh a PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS STUDY of ETHIOPIAN FOOTBALL DURING 2008-2018 Dr. Kanhaiya Kumar Singh, Assistant

International Journal of Physical Education, Health and Social Science (IJPEHSS) ISSN: 2278 – 716X www.ijpehss.org Vol. 7, Issue 1, (2018) Peer Reviewed, Indexed and UGC Approved Journal (48531) Impact Factor 5.02 A PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS STUDY OF ETHIOPIAN FOOTBALL DURING 2008-2018 Dr. Kanhaiya Kumar Singh, Assistant Professor Sports Academy, Bahirdar University, Ethiopia ABSTRACT The purpose of the study was to analyse the overall journey of Ethiopian National football at international level as well domestic level in last decade. In order to analyse the fact observation method has been used to collect data. Finding of the study reflects that Ethiopian national football is losing its position and credibility continuously in the last decade. It might be happened due to some socio-political issue the Ethiopian football federation, moreover for FIFA2014 Ethiopian national football team scored total 12 goals and conceded 21 goals and reached up to first qualifying round then Nigeria went to FIFA World Cup 2014. Further for FIFA 2018 (Russia), Ethiopian National Team reached up to second qualifying round and eliminated by COGO. Ethiopian Domestic football leagues are Premier League, Higher League and National League conducted every year, it is important to note that 70% winning position in Premier League went to one team i.e., Saint Gorge FC and rest 30% goes to other 15 playing teams. It clearly shows the lack of competitive balance in the most famous domestic league of a country. At the continent level in Champions League Country best domestic team scored 18th Rank out of 59 teams. In Super League (Winner of Champions League v/s Winners of Confederation Cup) Ethiopian football team has not seen anywhere. -

Backround Credits

1 BACKROUND Sport and Cooperation Network Foundation NGO with consultative status at the United Nations port Network started in 1999 with the aim of supporting Sand promoting health education and integration for children and youth in developing countries. Sport is used as a means of promoting peace and understanding in areas of conflict and refugees. Red Sports believes in the importance of sport as a core activity for human and social development, the values of effort, teamwork, and perseverance, as well as other social and health benefits make sport a powerful tool for development. It is with this belief and passion that Sports Network has carried out projects in Spain and abroad for over 13 years. Today, Sport Network has carried out 32 projects and 29 awareness integration in Spain, and has completed over 50 projects in 25 countries in Africa, Latin America and Central Europe. Awareness programs are conducted mainly in schools, sports clubs and universities. The purpose of these initiatives is to demonstrate how sport can help the Genta access to basic education, health care, promote integration in society and to promote peace and reconciliation in their communities in developing countries. Integration initiatives promoted intercultural exchange between the population of the host country and the immigrant community. CREDITS GRAPHIC DESIGNERS- Mary Austin & Donatas Jodauga 2 BACKROUND VISION Sport helps improve the lives of all people desfavorecidasy helps them to live in dignity, peace and better opportunities. MISSION We work with sports to promote education, health and integration of children and youth in developing countries. In conflict zones promote sport as a way to peace and understanding. -

Proceedings of the 16Th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies

www.svt.ntnu.no/ices16/ Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies Conference of the 16th International Proceedings Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies Volume 1 Volume 1 Volume Edited by Svein Ege, Harald Aspen, Birhanu Teferra and Shiferaw Bekele ISBN 978-82-90817-27-0 (printed) Det skapende universitet Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies Volume 1 Edited by Svein Ege, Harald Aspen, Birhanu Teferra and Shiferaw Bekele Department of Social Anthropology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, 2009 Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, ed. by Svein Ege, Harald Aspen, Birhanu Teferra and Shiferaw Bekele ISBN 978-82-90817-27-0 (printed) Vol. 1-4 http://www.svt.ntnu.no/ices16/ Printed in Norway by NTNU-trykk, Trondheim 2009 © The authors Table of contents Author index xv Preface xix Archaeology The Temple of Yeha: Geo-Environmental Implications on its Site Selection 1 and Preservation Asfawossen Asrat The Archaeology of Islam in North East Shoa 11 Kassaye Begashaw History A Miracle of the Archangel Uriel Worked for Abba Giyorgis of Gasəcca 23 Getatchew Haile Ras Wäsän Säggäd, a Pre-Eminent Lord of Early 16th-Century Ethiopia 37 Michael Kleiner T.aytu’s Foremothers. Queen Əleni, Queen Säblä Wängel and Bati Dəl 51 Wämbära Rita Pankhurst Ase Iyasu I (1682-1706) and the synod of Yébaba 65 Verena Böll Performance and Ritual in Nineteenth-Century Ethiopian Political Culture 75 Izabela Orlowska Shäwa, Ethiopia's Prussia. Its Expansion, Disappearance and Partition 85 Alain Gascon Imprints of the Time : a Study of the hundred Ethiopian Seals of the Boucoiran 99 collection Serge Tornay and Estelle Sohier The Hall Family and Ethiopia. -

PDF Download

Integrated Blood Pressure Control Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Knowledge and Attitude of Self-Monitoring of Blood Pressure Among Adult Hypertensive Patients on Follow-Up at Selected Public Hospitals in Arsi Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Integrated Blood Pressure Control Addisu Dabi Wake 1 Background: Self-monitoring of blood pressure (BP) among hypertensive patients is an Daniel Mengistu Bekele 2 important aspect of the management and prevention of complication related to hypertension. Techane Sisay Tuji 1 However, self-monitoring of BP among hypertensive patients on scheduled follow-up in hospitals in Ethiopia is unknown. The aim of the study was to assess knowledge and attitude 1Nursing Department, College of Medical and Health Sciences, Arsi University, of self-monitoring of BP among adult hypertensive patients. Asella, Ethiopia; 2School of Nursing and Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted on 400 adult hypertensive patients attend- Midwifery, College of Health Sciences, ing follow-up clinics at four public hospitals of Arsi Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia The data were collected from patients from March 10, 2019 to April 8, 2019 by face-to-face interview using a pretested questionnaire and augmented by a retrospective patients’ medical records review. The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 21.0 software. Results: A total of 400 patients were enrolled into the study with the response rate of 97.6%. The median age of the participants was 49 years (range 23–90 years). -

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 and Reassessment of Crop

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 And Reassessment Of Crop Production and Marketing For 2014/15 October 2015 Final Report Ethiopia: Bellmon Analysis - 2014/15 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Economic Background ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Poverty ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Wage Labor ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Agriculture Sector Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

2016 Olympic Games Statistics – Men's 10000M

2016 Olympic Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m by K Ken Nakamura Record to look for in Rio de Janeiro: 1) Last time KEN won gold at 10000m is back in 1968. Can Kamworor, Tanui or Karoki change that? 2) Can Mo Farah become sixth runner to win back to back gold? Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:01.17 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 1 Beijing 2008 2 2 27:02.77 Sileshi Sihine ETH 2 Beijing 2008 3 3 27:04.11 Micah Kogo KEN 3 Beijing 2008 4 4 27:04.11 Moses Masai KEN 4 Beijing 2008 5 27:05.10 Kenenisa Bekele 1 Athinai 2004 6 5 27:05.11 Zersenay Tadese ERI 5 Beijing 2008 7 6 27:06.68 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 6 Beijing 2008 8 27:07.34 Haile Gebrselassie 1 Atlanta 1996 Slowest winning time since 1972: 27:47.54 by Alberto Cova (ITA) in 1984 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Nat Venue Year Max 47.8 29:59.6 Emil Zatopek TCH London 1948 18.68 27:47.54 Alberto Cova ITA Los Angeles 1984 Min 0.09 27:18.20 Haile Gebrselassie ETH Sydney 2000 Second line is largest margin since 1952 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 27:01.17 Kenenisa Bekele ETH Beijing 2008 2 27:02.77 Sileshi Sihine ETH Beijing 2008 3 27:04.11 Micah Kogo KEN Beijing 2008 4 27:04.11 Moses Masai KEN Beijing 2008 5 27:05.11 Zersenay Tadese ERI Beijing 2008 6 27:06.68 Haile Gebrselassie ETH Beijing 2008 7 27:08.25 Martin Mathathi KEN Beijing 2008 Multiple Gold Medalists: Kenenisa Bekele (ETH): 2004, 2008 Haile Gebrselassie (ETH): 1996, 2000 Lasse Viren (FIN): 1972, 1976 Emil -

Elite Athletes

ATHLETES ELITE MEDELITIA INFOE & FASTATHL FAECTTSES TABLE OF CONTENTS ELITE ATHLETES ELITE ATHLETE ROSTER ............................................................................................ 28 MALE ATHLETE PROFILES Raji Assefa .............................................................................................................. 30 Diego Colorado ........................................................................................................ 32 Shami Dawit ............................................................................................................ 34 Jeffrey Eggleston ...................................................................................................... 35 Jimmy Grabow .......................................................................................................... 37 Jason Gutierrez ........................................................................................................ 38 Takashi Horiguchi ..................................................................................................... 39 Hiroki Kadota ........................................................................................................... 40 Tsegaye Kebede ....................................................................................................... 41 Bernard Kipyego ....................................................................................................... 43 Michael Kipyego ...................................................................................................... -

Economic Returns of Foliar Fungicides Application to Control Yellow Rust in Bread Wheat Cultivars in Arsi High Lands of Ethiopia

Current Investigations in Agriculture and Current Research DOI: 10.32474/CIACR.2021.09.000317 ISSN: 2637-4676 Research Article Economic Returns of Foliar Fungicides Application to Control Yellow Rust in Bread Wheat Cultivars in Arsi high lands of Ethiopia Alemu Ayele Zerihun* and Getnet Muche Abebele Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), Kulumsa Agricultural Research Center, Asella, Ethiopia *Corresponding author: Alemu Ayele Zerihun, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), Kulumsa Agricultural Research Center, Asella, Ethiopia Received: April 21, 2021 Published: May 17, 2021 Abstract Wheat yellow rust caused by Puccinic Striiformis f. sp tritici is the most widespread and destructive disease of wheat, especially in the highlands of Ethiopia. Application of foliar fungicides are important mechanisms to control wheat yellow rust disease. The activity was conducted at two experimental sites Meraro and Bekoji in 2018 main cropping season, in order to determine net returns of wheat yields from the application of fungicides. The aim of the study was to know net reruns obtained from the application of propiconazole and Thiophanate-methyl 310g/l +Epoxiconazole 187g/l fungicides with twice application frequency in four bread wheat cultivars with different resistance level, being susceptible, moderately susceptible, moderately resistant and resistant including Kubsa, Danda’a, Lemu and Wane against wheat yellow rust respectively in 2018. The positive net returns at Meraro, 12.66, 11.4, 8.39 and 7.65, and at Bekoji 12.14, 11.4, 7.92 and 5.18 on Kubsa, Lemu, Danda’a and Wane (susceptible, moderately susceptible, moderately resistant and resistant bread wheat varieties by the twice application of RexDuo respectively. -

Oromia Region Administrative Map(As of 27 March 2013)

ETHIOPIA: Oromia Region Administrative Map (as of 27 March 2013) Amhara Gundo Meskel ! Amuru Dera Kelo ! Agemsa BENISHANGUL ! Jangir Ibantu ! ! Filikilik Hidabu GUMUZ Kiremu ! ! Wara AMHARA Haro ! Obera Jarte Gosha Dire ! ! Abote ! Tsiyon Jars!o ! Ejere Limu Ayana ! Kiremu Alibo ! Jardega Hose Tulu Miki Haro ! ! Kokofe Ababo Mana Mendi ! Gebre ! Gida ! Guracha ! ! Degem AFAR ! Gelila SomHbo oro Abay ! ! Sibu Kiltu Kewo Kere ! Biriti Degem DIRE DAWA Ayana ! ! Fiche Benguwa Chomen Dobi Abuna Ali ! K! ara ! Kuyu Debre Tsige ! Toba Guduru Dedu ! Doro ! ! Achane G/Be!ret Minare Debre ! Mendida Shambu Daleti ! Libanos Weberi Abe Chulute! Jemo ! Abichuna Kombolcha West Limu Hor!o ! Meta Yaya Gota Dongoro Kombolcha Ginde Kachisi Lefo ! Muke Turi Melka Chinaksen ! Gne'a ! N!ejo Fincha!-a Kembolcha R!obi ! Adda Gulele Rafu Jarso ! ! ! Wuchale ! Nopa ! Beret Mekoda Muger ! ! Wellega Nejo ! Goro Kulubi ! ! Funyan Debeka Boji Shikute Berga Jida ! Kombolcha Kober Guto Guduru ! !Duber Water Kersa Haro Jarso ! ! Debra ! ! Bira Gudetu ! Bila Seyo Chobi Kembibit Gutu Che!lenko ! ! Welenkombi Gorfo ! ! Begi Jarso Dirmeji Gida Bila Jimma ! Ketket Mulo ! Kersa Maya Bila Gola ! ! ! Sheno ! Kobo Alem Kondole ! ! Bicho ! Deder Gursum Muklemi Hena Sibu ! Chancho Wenoda ! Mieso Doba Kurfa Maya Beg!i Deboko ! Rare Mida ! Goja Shino Inchini Sululta Aleltu Babile Jimma Mulo ! Meta Guliso Golo Sire Hunde! Deder Chele ! Tobi Lalo ! Mekenejo Bitile ! Kegn Aleltu ! Tulo ! Harawacha ! ! ! ! Rob G! obu Genete ! Ifata Jeldu Lafto Girawa ! Gawo Inango ! Sendafa Mieso Hirna -

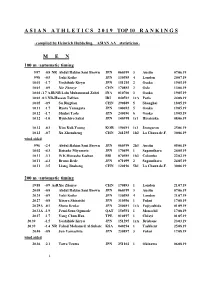

2019 TOP10-Rankings

A S I A N A T H L E T I C S 2 0 1 9 TOP 10 R A N K I N G S - compiled by Heinrich Hubbeling, ASIAN AA – statistician - M E N 100 m / automatic timing 9.97 +0.8 NR Abdul Hakim Sani Brown JPN 060399 3 Austin 07.06.19 9.98 +0.5 Yuki Koike JPN 130595 4 London 20.07.19 10.01 +1.7 Yoshihide Kiryu JPN 151295 2 Osaka 19.05.19 10.01 +0.9 Xie Zhenye CHN 170893 2 Oslo 13.06.19 10.03 +1.7 AJR/NR Lalu Muhammad Zohri INA 010700 3 Osaka 19.05.19 10.03 -0.3 NR=Hassan Taftian IRI 040593 1rA Paris 24.08.19 10.05 +0.9 Su Bingtian CHN 290889 5 Shanghai 18.05.19 10.11 +1.7 Ryota Yamagata JPN 100692 5 Osaka 19.05.19 10.12 +1.7 Shuhei Tada JPN 240696 6 Osaka 19.05.19 10.12 +1.0 Ryuichiro Sakai JPN 140398 1s1 Hiratsuka 08.06.19 10.12 -0.3 Kim Kuk-Young KOR 190491 1s1 Jeongseon 25.06.19 10.12 +0.7 Xu Zhouzheng CHN 261295 1h2 La Chaux-de-F. 30.06.19 wind-aided 9.96 +2.4 Abdul Hakim Sani Brown JPN 060399 2h3 Austin 05.06.19 10.02 +4.3 Daisuke Miyamoto JPN 170499 1 Sagamihara 24.05.19 10.11 +3.1 W.K.Himasha Eashan SRI 070595 1h3 Colombo 22.02.19 10.11 +4.3 Bruno Dede JPN 071099 2 Sagamihara 24.05.19 10.11 +3.5 Liang Jinsheng CHN 120196 5h1 La Chaux-de-F. -

Doha 2018: Compact Athletes' Bios (PDF)

Men's 200m Diamond Discipline 04.05.2018 Start list 200m Time: 20:36 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Rasheed DWYER JAM 19.19 19.80 20.34 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 20.08.09 2 Omar MCLEOD JAM 19.19 20.49 20.49 AR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 NR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 3 Nethaneel MITCHELL-BLAKE GBR 19.94 19.95 WJR 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM Hamilton 11.04.04 4 Andre DE GRASSE CAN 19.80 19.80 MR 19.85 Ameer WEBB USA 06.05.16 5 Ramil GULIYEV TUR 19.88 19.88 DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Bruxelles 16.09.11 6 Jereem RICHARDS TTO 19.77 19.97 20.12 SB 19.69 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria 16.03.18 7 Noah LYLES USA 19.32 19.90 8 Aaron BROWN CAN 19.80 20.00 20.18 2018 World Outdoor list 19.69 -0.5 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria 16.03.18 19.75 +0.3 Steven GARDINER BAH Coral Gables, FL 07.04.18 Medal Winners Doha previous Winners 20.00 +1.9 Ncincihli TITI RSA Columbia 21.04.18 20.01 +1.9 Luxolo ADAMS RSA Paarl 22.03.18 16 Ameer WEBB (USA) 19.85 2017 - London IAAF World Ch. in 20.06 -1.4 Michael NORMAN USA Tempe, AZ 07.04.18 14 Nickel ASHMEADE (JAM) 20.13 Athletics 20.07 +1.9 Anaso JOBODWANA RSA Paarl 22.03.18 12 Walter DIX (USA) 20.02 20.10 +1.0 Isaac MAKWALA BOT Gaborone 29.04.18 1.