Tin Pan Alley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

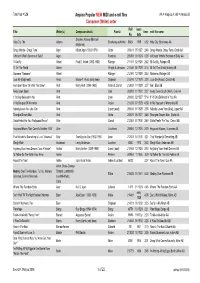

Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and E-Roll Files Composer

Total files = 536 Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and e-roll files AA = Ampico A, AB = Ampico B Composer (Writer) order Roll issue Title Writer(s) Composer details Pianist time midi file name No. date Stephen Adams (Michael Holy City, The Adams Brockway as Kmita 56824 1919 4:52 Holy City, Brockway AA Maybrick) Crazy Words - Crazy Tune Ager Milton Ager (1893-1979) Grofe 208611 05 1927 2:48 Crazy Words, Crazy Tune, Grofe AA I Wonder What's Become of Sally? Ager Fairchild 205191 09 1924 4:28 I Wonder What's Become of Sally AA I'll Get By Ahlert Fred E. Ahlert (1892-1953) Rainger 211171 02 1929 2:42 I'll Get By, Rainger AB I'll Tell The World Ahlert Wright & Johnston 211541 05 1929 3:14 I'll Tell The World (Ahlert) AB Marianne "Marianne" Ahlert Rainger 212191 12 1929 2:44 Marianne, Rainger AB Love Me (Deja) waltz Aivaz Morse-T. Aivaz (only item) Shipman 212241 12 1929 3:20 Love Me (Aivaz), Carroll AB Am I Blue? from "On With The Show" Akst Harry Akst (1894-1963) Arden & Carroll 212031 10 1929 3:37 Am I Blue AB Away Down South Akst Clair 203051 11 1922 2:37 Away Down South (Akst), Clair AA If I'd Only Believed In You Akst Lane 208383 02 1927 5:14 If I'd Only Believed In You AA In My Bouquet Of Memories Akst Arden 210233 07 1928 4:58 In My Bouquet of Memories AB Nobody Loves You Like I Do Akst Lopez (asst) 205531 01 1925 2:38 Nobody Loves You (Akst), Lopez AA Shanghai Dream Man Akst Grofe 208621 05 1927 3:48 Shanghai Dream Man, Grofe AA Gotta Feelin' For You "Hollywood Revue" Alter Carroll 212351 01 1930 2:49 Gotta Feelin' For You, Carroll AB Hugs and -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Manuel Y. Ferrer and Miguel S. Arévalo: Premier Guitarist-Composers in Nineteenth-Century California

Manuel Y. Ferrer and Miguel S. Arévalo: Premier Guitarist-Composers in Nineteenth-Century California John Koegel THE MUSICAL CAREERS of Manuel Y. Ferrer and vited soloists before both Mexican and non-Mexican Miguel S. Arévalo, the premier Mexican-American audiences. Arévalo and Ferrer also taught music to guitarist-composers in nineteenth-century California, pupils of diverse social and ethnic backgrounds. demonstrate that local Hispanic musicans continued Both exerted significant influence on musical 1ife in to represent Mexican cultural traditions advanta their respective areas of California. geously at a time when Anglo-American and Euro pean musicians dominated the state's forma] public Manuel Ygnacio Ferrer (born May 1832, 2 San performance scene. Though born in Mexico, both Antonio, Baja California?;3 died 1 June 1904, Oak- men lived most of their lives in California, Ferrer in 2 Reports published in 1904 immediately after Ferrer's death the San Francisco Bay area, and Arévalo in Los (including his obituary) give his birth year as 1832. The 1900 Angeles. Both toured throughout the state1 and fre Federal Census lists Ferrer's address at 5730 Telegraph Avenue, quently performed in their home cities, playing Mex Oakland (next door to his friend Spanish composer and pianist ican, European, and European-Arnerican music for Santiago Arrillaga). lt also gives his birth year as 1832 (1900 Mexican-American and English-speaking audiences. Federal Census: State of California, City of Oakland, enumer ation number 388, street number 8, lines 60-63). Ferrer and Arévalo were also published composers. 3 My search of the church records from San Antonio, Baja They moved easily between the Spanish- and En California failed to reveal the baptismal record of Manuel glish-speaking communities, often appearing as in- Ferrer. -

Maud Powell As an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 "The Solution Lies with the American Women": Maud Powell as an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C. Williams Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC “THE SOLUTION LIES WITH THE AMERICAN WOMEN”: MAUD POWELL AS AN ADVOCATE FOR VIOLINISTS, WOMEN, AND AMERICAN MUSIC By CATHERINE C. WILLIAMS A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Catherine C. Williams defended this thesis on May 9th, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Thesis Michael Broyles Committee Member Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Maud iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents and my brother, Mary Ann, Geoff, and Grant, for their unceasing support and endless love. My entire family deserves recognition, for giving encouragement, assistance, and comic relief when I needed it most. I am in great debt to Tristan, who provided comfort, strength, physics references, and a bottomless coffee mug. I would be remiss to exclude my colleagues in the musicology program here at The Florida State University. The environment we have created is incomparable. To Matt DelCiampo, Lindsey Macchiarella, and Heather Paudler: thank you for your reassurance, understanding, and great friendship. -

I Didn't Raise My Boy to Be A…” Mothers, Music, and the Obligations

GREAT WAR, FLAWED PEACE, AND THE LASTING LEGACY OF WORLD WAR I I “I DIDN’T RAISE MY BOY TO BE A…” MOTHERS, MUSIC, AND OBLIGATIONS OF WAR GUIDING QUESTION: How did the idea of a mother’s sacrifice impact how World War I was viewed? AUTHOR STANDARDS CONNECTIONS Jennifer Camplair CONNECTIONS TO COMMON CORE Lorena High School › CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2 Determine the central Lorena, Texas ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the WHY? relationships among the key details and ideas. Mothers had an enormous impact on the American › CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.4 Interpret words and public supporting the war. As women gained more phrases as they are used in a text, including determining political agency, their voices of approval or disapproval technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze for their sons' service were vital to the war effort. how specific word choices shape meaning or tone. › CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.5 Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and OVERVIEW larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or Using the cover and lyrics from two popular songs of stanza) relate to each other and the whole. the time, photographs, and primary source analysis, students will evaluate how popular culture sought to influence mothers’ support of the war and how the DOCUMENTS USED government recognized their sacrifice with Gold Star PRIMARY SOURCES Mothers’ Pilgrimages to their sons’ and daughters' final Leo Friedman and Helen Wall, “I Didn’t Raise My Boy To Be A resting places. -

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

Beowulf Beowulf Is Part of the Heritage of Every English-Speaking Person—The Eowulf Oldest Literary Work in Our Language

BEOWULF Beowulf is part of the heritage of every English-speaking person—the EOWULF oldest literary work in our language. Ken Pickering, who lives in the B shadow of Canterbury Cathedral, follows the epic poem closely, but with amusing anachronisms to make it meaningful and entertaining for modern theatregoers of all ages. Book and lyrics by “A stunning rock musical of unusually strong construction ... The score has some magnificent numbers, almost ‘rock-Wagnerian’ in concept.” KEN PICKERING (Amateur Stage) Music by Rock musical. Book and lyrics by Ken Pickering. Music by Keith Cole. Cast: 4m., 3w., extras. As the Vikings revel in the mead hall, the KEITH COLE monster Grendel enters and slays several warriors. Beowulf arrives, fights Grendel single-handedly, tears off the monster’s arm (really!—right there on stage!), and sends him home to die. Beowulf is hailed as a hero and marries Princess Hygd, and the revels begin again until Grendel’s mother, even more ferocious, comes for revenge. As a contrast to the ancient Viking story, Grendel is depicted as a punk rocker; his mother is “Big Mummy.” The play’s themes—the struggle against violence, vandalism and darkness, and the stupidity in assuming that affluence brings real security or satisfaction—are as relevant today as ever. The Viking blend of sheer energy and raw humor, hero worship and action are as familiar to the theatre, the football field, or the rock concert as they were to King Hrothgar in his great drinking hall of Heorot—why not join him there? The action takes place in the world of the Vikings in the 5th century A.D. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Sousa Cover the ONE.Qxd 24/7/08 2:38 Pm Page 1

Sousa cover THE ONE.qxd 24/7/08 2:38 pm Page 1 Chan 4535 CHANDOS BRASS FROM MAINE TO OREGON THE WILLIAMS FAIREY BAND PLAYS SOUSA MARCHES CONDUCTED BY MAJOR PETER PARKES CHAN 4535 BOOK.qxd 24/7/08 2:41 pm Page 2 Sousa Marches 1 Semper Fidelis arr. C.W. Hewitt 2:55 2 The Crusader arr. Peter Parkes 3:36 3 El Capitan March 2:33 4 The Invincible Eagle arr. Peter Parkes 3:47 5 King Cotton 2:58 6 Hands across the Sea arr. Peter Parkes 2:57 7 Manhattan Beach arr. C.W. Hewitt 2:25 8 Our Flirtations arr. James Howe 2:43 9 The Picadore arr. Peter Parkes 2:58 10 The Gladiator March 2:58 11 The Free Lance arr. Norman Richardson 4:33 12 The Washington Post arr. C.W. Hewitt 2:46 13 The Beau Ideal arr. Peter Parkes 3:36 14 The High School Cadets arr. John Hartmann 2:45 15 The Fairest of the Fair arr. Norman Richardson 3:50 16 The Thunderer arr. Harry Mortimer 2:57 17 The Occidental arr. Peter Parkes 2:55 18 The Liberty Bell arr. J. Ord Hume 3:49 19 The Corcoran Cadets arr. Peter Parkes 3:15 John Philip Sousa (1854–1932) 20 National Fencibles March arr. Norman Richardson 3:36 Royal College of Music 21 The Black Horse Troop arr. Peter Parkes 3:34 22 The Gridiron Club March arr. James Howe 3:38 23 The Directorate arr. Norman Richardson 2:38 24 The Belle of Chicago arr. -

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in His Early Songs

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in his Early Songs A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2011 by Kimberly Gelbwasser B.M., Northwestern University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 Committee Chair: Steven Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, millions of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe as well as the Mediterranean countries arrived in the United States. New York City, in particular, became a hub where various nationalities coexisted and intermingled. Adding to the immigrant population were massive waves of former slaves migrating from the South. In this radically multicultural environment, Irving Berlin, a Jewish- Russian immigrant, became a songwriter. The cultural interaction that had the most profound effect upon Berlin’s early songwriting from 1907 to 1914 was that between his own Jewish population and the African-American population in New York City. In his early songs, Berlin highlights both Jewish and African- American stereotypical identities. Examining stereotypical ethnic markers in Berlin’s early songs reveals how he first revised and then traded his old Jewish identity for a new American identity as the “King of Ragtime.” This document presents two case studies that explore how Berlin not only incorporated stereotypical musical and textual markers of “blackness” within two of his individual Jewish novelty songs, but also converted them later to genres termed “coon” and “ragtime,” which were associated with African Americans.