Bank and Investor Risk Policies on Soft Commodities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDANCE Position Management Regime for ICE Futures Europe

GUIDANCE Position Management Regime for ICE Futures Europe Soft Commodities September 2018 Copyright IntercontinentalExchange, Inc. 2015. All Rights Reserved www.theice.com Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Accountability Levels 4 3. Delivery Limits 5 4. Delivery Limit Exemptions 5 5. Aggregation 12 6. Enforcement 12 7. Changes to the Accountability Levels, Delivery Limits and Delivery Limit Exemption levels 13 Attachment 1 14 ICE Futures Europe – September 2018 Page 2 of 15 www.theice.com ICE Futures Europe Implementation of the Position Management Regime for ICE Futures Europe Soft Commodities 1. Introduction 1.1. In accordance with Rules A.2 and G.2 the Exchange may adopt such procedures as it deems appropriate to establish. With respect to Rule P.0A, this shall include procedures in respect of any specified delivery/expiry month of any Exchange Contract, or in the case of ICE Futures Europe London Cocoa and Euro Cocoa Contracts, a group of Exchange Contracts, or in respect of a combination of delivery/expiry months thereof, limits on the maximum open position that may be held by a Member for his own account or on behalf of his Client. 1.2. The purpose of this Guidance Document ("Guidance Document") is then to set out, pursuant to Rule P.0A, the procedures and associated guidance in respect of the regime for the monitoring and regulation of ICE Futures Europe London Cocoa and Euro Cocoa (for the purposes of this Guidance, “the Cocoa Contracts”), Robusta Coffee, White Sugar and Containerised White Sugar ( for the purposes of this Guidance “the Sugar Contracts”) and Wheat Futures and Options Contracts (collectively, the “Soft Commodity Contracts”). -

Introduction

THE IMPLEMENTATION LIMITATIONS OF AND ALTERNATIVE POLICY SOLUTIONS FOR INDONESIA’S REDD+ PROGRAM CONCERNING PEATLAND RESTORATION Sarah Guzick Student, Political Science Yale University Class of 2013 Nicholas Robinson Adjunct Professor, Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Yale University Recent increases in global demand for palm oil have resulted in rapid, widespread de- forestation in Indonesia, making Indonesia the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world. Although the Indonesian government has sought to pursue progres- sive environmental policies to curb deforestation, such as through REDD+, implementation has been hampered by legal loopholes, corruption and weak rule of law. This paper will examine two alternative carbon sequestration policies to REDD+: a drying up of the palm oil market and a buy-out of palm oil plantations. Introduction Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous country, is an archipelago of over 17,000 islands. It possesses 50 per cent of global tropical peatlands, where layers of forest debris of up to 15,000 years old accumulate be- cause they are too wet to decompose. These peatlands are a dual ecosystem, consisting of an acidic swamp base of perpetually submerged plants up to 15 m deep and tropical trees that grow on top of that swamp base. The 22 million ha of peat swamp forests in Indonesia are a storage source of carbon, sequestering in these wetlands 196 tons of carbon per ha, equivalent to 30 times as much carbon as above ground forests sequester.1 Because of these carbon stores, their role in climate change is incredibly important, because destruction of peatlands would release large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. -

Exploring Environmental Tradeoffs in Soft Commodity Production

Exploring Environmental Tradeoffs in Soft Commodity Production Jen Bowe, Kenny Fahey, Mallory McLaughlin, Julia Ruedig, Sheena VanLeuven, Jay Wolfgram March 2013-April 2014 Modeling Environmental Tradeoffs in Soft Commodity Production 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Transforming Markets: The 2050 Criteria .................................................................................. 5 Beyond The 2050 Criteria: Sustainable Sourcing....................................................................... 6 Commodity Sourcing and Environmental Tradeoffs .................................................................. 7 Project Goals and Objectives .......................................................................................................... 9 Research Methodology ................................................................................................................. 11 Research Sources....................................................................................................................... 11 Commodity Research ................................................................................................................ 12 Environmental Indicators .......................................................................................................... 13 Dimensions of Environmental Tradeoffs ................................................................................. -

Unilever's Palm Oil Grievance Tracker

Unilever’s Palm Oil Grievance Tracker Updated May 1, 2020 This document lists grievances that have been raised to Unilever with regards to our palm oil supply chain. Unilever defines a palm oil grievance as a complaint sent to Unilever about an alleged breach of our Sustainable Palm Oil Sourcing Policy (PDF | 167KB) and/or our Responsible Sourcing Policy (PDF | 9MB). Unilever works closely with our suppliers, grievance raisers, and other stakeholders to investigate and resolve issues within our supply chain in a timely, transparent, and effective manner. A. Direct suppliers¹ with supply chain grievances B. Third-party/indirect suppliers² with supply chain grievances 11 37 Supplier Name References Supplier Name References Supplier Name References 1 ADM A4, A6, B6, B16 1 Agra Bumi Niaga A6, B5 21 Korindo B15 2 Apical/Asian Agri A4, A7, B15, B18 2 Anglo-Eastern Plantations B11, B15 22 Laot Bangko B19 3 Bunge LC/IOI A1, A4, A6, A7, B6, B16, B18, B19 3 Austindo Nusantara Jaya B4, B15, B16, B18 23 Mulia Sawit Agro B18, B22 4 A4, A6, A7, A11, B6, B9, B15, B16, Cargill 4 Bintang Harapan Desa B13 24 Noble Group B8, B15 B18, B19 5 Emami Agrotech A9 5 Best Group B7, B22 25 NPC Resources B15 A3, A4, A6, A7, B4, B5, B6, B14, 6 GAR 6 BLD Plantations B18 26 PT Perkebunan Nusantara I B19 B15, B16, B19, B20 7 KLK A2, A7, B16 7 Bumitama B15 27 Pundi Lahan Khatulistiwa group B17 8 Louis Dreyfus A4, B16 8 CAA/First Resources B10, B18 28 Rimbunan Hijau B15 A4, A6, A7, B3, B4, B5, B6, B8, B10, Central Cipta Murdaya/ 9 Musim Mas 9 B15 29 Samling/Glenealy B15 -

Palm Oil Grievance Log Published November 2020

The Hershey Company’s Palm Oil Grievance Log Published November 2020 This log records grievances Hershey receives that are in direct violation of our Responsible Palm Oil Sourcing Policy and occur in our palm oil supply chain. The log will be updated on our website at the beginning of each month. The grievances listed are reported based on Hershey’s awareness at the time of publication. Grievance Log Updates In October 2020, one new grievance was raised to Hershey, related both to deforestation and/or peatland development and to human rights and labor abuses. Of the 32 grievances logged to date, four are being investigated, 20 are being monitored and eight are closed. Closed grievances may include those which resulted in the suspension of a company. In October 2020, Hershey issued no new No Buy orders. We currently have No Buy orders placed on 13 palm companies: 1) Indofood Agri Resources/ Salim Group – issued February 2018 2) PT Surya Panen Subur (SPS/SPS II) – issued November 2018 3) FGV Holdings Bhd (formerly Felda) – issued December 2018 4) Samling Group – issued April 2020 5) Mulia Sawit Group – issued April 2020 6) PT Indo Sawit Perkasa – issued June 2020 7) PT Indo Alam – issued June 2020 8) PT Laot Bangko – issued June 2020 9) Ciliandry Anky Abadi – issued August 2020 10) Indonusa – issued September 2020 11) PT Kallista Alam – issued September 2020 12) PT Permata Hijau – issued September 2020 13) Tunas Baru Lampung/Sungai Budi – issued September 2020 In October 2020, no suspended palm company was granted re-entry into our supply chain. -

Overview of the World's Commodity Exchanges – 2007

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Overview of the world’s commodity exchanges – 2007 Study prepared by the UNCTAD secretariat United Nations New York and Geneva, 2009 Overview of the world’s commodity exchanges – 2007 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat at: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of UNCTAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of this authorities or concerning the definition of its frontiers or boundaries. This document was prepared by Leonela Santana-Boado and Adam Gross of the UNCTAD secretariat, with substantial input and research assistance provided by Ms. Leticia Gennes Beltrán. The extensive contributions of Alexander Belozertsev to the sections on Russia and Ukraine are also gratefully acknowledged. Recent publications by the UNCTAD secretariat on the subject of commodity exchanges include “Overview of the world’s commodity -

Financialization and the Returns to Commodity Investments Scott Main

Financialization and the Returns to Commodity Investments Scott Main, Scott H. Irwin, Dwight R. Sanders, and Aaron Smith* April 2018 Forthcoming in the Journal of Commodity Markets *Scott Main is a former graduate student in the Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Scott H. Irwin is the Lawrence J. Norton Chair of Agricultural Marketing, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Dwight R. Sanders is a Professor, Department of Agribusiness Economics, Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Aaron Smith is a Professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California-Davis. Financialization and the Returns to Commodity Investments Abstract Commodity futures investment grew rapidly after their popularity exploded—along with commodity prices—in the mid-2000s. Numerous individuals and institutions embraced alternative investments for their purported diversification benefits and equity-like returns. We investigate whether the “financialization” of commodity futures markets reduced the risk premiums available to long-only investors in commodities. While energy futures markets generally exhibit a decline in risk premiums after 2004, premiums in all but one non-energy futures market actually increased over the same time period. Overall, the average unconditional return to individual commodity futures markets is approximately equal to zero before and after financialization. Key words: commodity, financialization, futures prices, index fund, investments, risk premium, storable JEL categories: D84, G12, G13, G14, Q13, Q41 Financialization and the Returns to Commodity Investments Introduction Several influential studies published in the last 15 years (e.g., Gorton and Rouwenhorst 2006, Erb and Harvey 2006) concluded that long-only commodity futures investments generate equity-like returns.1 This undoubtedly contributed to the rise of commodity futures from relative obscurity to a common feature in today’s investing landscape. -

What Drives Commodity Price Booms and Busts?

What Drives Commodity Price Booms and Busts? David S. Jacks and Martin Stuermer Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Research Department Working Paper 1614 What drives commodity price booms and busts?* David S. Jacks (Simon Fraser University and NBER) Martin Stuermer (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Research Department) November 2016 Abstract What drives commodity price booms and busts? We provide evidence on the dynamic effects of commodity demand shocks, commodity supply shocks, and inventory demand shocks on real commodity prices. In particular, we analyze a new data set of price and production levels for 12 agricultural, metal, and soft commodities from 1870 to 2013. We identify differences in the type of shock driving prices of the various types of commodities and relate these differences to commodity types which reflect differences in long-run elasticities of supply and demand. Our results show that demand shocks strongly dominate supply shocks. * The views in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System. Jacks gratefully acknowledges the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada for research support. We are grateful for comments and suggestions from participants at the Summer Meeting of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, at the Bank of Canada and Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas joint conference on commodity price cycles, at the Norges Bank/CAMP workshop, and at seminars at the Bundesbank and the European Central Bank. 1 JEL classification: E30, Q31, Q33, N50 Keywords: Commodity prices, natural resources, structural VAR 1. -

Burning Paradise the Oil Palm Practices of Korindo in Papua and North Maluku

Burning Paradise The oil palm practices of Korindo in Papua and North Maluku Commissioned by Mighty, the Korea Federation for Environmental Movements, SKP-KAMe Merauke and PUSAKA August 2016 Photo: Pristine forest in Papua © Greenpeace / Ardiles Rante, 2008 Photo: Korindo having cleared forest for oil palm in Papua © Mighty; 4 June 2016; Latitude 6°45'43.49"S, Longitude 140°48'27.70"E; Credit: Yudhi Mahendra 2 Colophon Aidenvironment report: Burning Paradise: The oil palm practices of Korindo in Papua and North Maluku Commissioned by: Mighty, the Korea Federation for Environmental Movements, SKP-KAMe Merauke and PUSAKA Date: August 2016 Mighty: Address: 2000 M St NW #720, Washington, DC 20036, United States. E-mail: [email protected] Cover photo: Smoke rising from burning wood rows in Korindo’s PT Berkat Cipta Abadi concession ©Ardiles Rante/Greenpeace; 26 March 2013 Aidenvironment Jalan Burangrang No. 18 Bogor 16153, West Java, Indonesia +62 (0) 251 837 1219 E-mail: [email protected] www.aidenvironment.org Aidenvironment is part of Stichting AERA, registered at the Chamber of Commerce of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, number 41208024 3 Burning paradise: The oil palm practices of Korindo in Papua and North Maluku Executive summary 5 Foreword 7 1. Korindo’s oil palm businesses 9 1.1 Plantations 9 1.2 Introduction to Papua 11 1.3 Introduction to South Halmahera 12 2. Practices and sustainability commitments 13 2.1 Practice: extensive deforestation 13 2.2 Practice: systematic use of fire to clear land 15 2.3 Practice: denial of community rights 18 2.4 Forests at risk of being cleared 20 2.5 Commitments 21 3. -

Bloomberg Link

Market Commentary 1 Energy 6 Bloomberg Commodity Outlook – May 2018 Edition Metals 9 Agriculture 14 Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM) DATA PERFORMANCE: 17 Overview, Commodity TR, Prices, Volatility Broad Commodities Taking the Bull Horns CURVE ANALYSIS: 22 Contango/Backwardation, - Commodity bull appearing young & vibrant vs. mature stock market Roll Yields, Forwards/Forecasts - Carry is a positive but crude oil prices remain extended MARKET FLOWS: 25 - Copper to gold: metals in bull-market transition with stocks Open Interest, Volume, COT, ETFs - Agriculture indicates early recovery from loss-of-faith lows - A potential commodities perfect storm is brewing for 2018 Gold Outlook Webinar – May 3, 10:00 EDT Commodity Investing Outlook Webinar – May 9, 11:00 EDT Data and outlook as of April 30 Mike McGlone – BI Senior Commodity Strategist BI COMD (the commodity dashboard) recipe for higher commodity prices. The nascent Commodity Bull Appears Young and commodity bull is gaining on the elderly stock-market Vibrant Vs. Mature Stock Market rally. A sustained dollar recovery is a key risk, but Performance: April +2.7%, YTD +2.3%, Spot +3.4%. unlikely. (Returns are total return (TR) unless noted) Commodities Looking Beyond April Dollar Gain. (Bloomberg Intelligence) -- Less than three years into a Despite a sharp recovery in the dollar, commodities' recovery, commodities are gaining momentum vs. the divergent strength in April indicates their outperformance decade-long rally in stocks. Favorable demand vs. supply vs. equities and bonds should accelerate. The 2018 and a multiyear price decline vs. bottoming equity-market increase of about 3% through April vs. a flat S&P 500 volatility from the lowest in decades should continue to may be just the beginning as the Bloomberg Commodity favor commodities. -

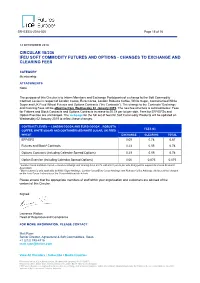

Circular 18/236 Ifeu Soft Commodity Futures and Options - Changes to Exchange and Clearing Fees

SR-ICEEU-2018-025 Page 15 of 16 14 DECEMBER 2018 CIRCULAR 18/236 IFEU SOFT COMMODITY FUTURES AND OPTIONS - CHANGES TO EXCHANGE AND CLEARING FEES CATEGORY Membership ATTACHMENTS None The purpose of this Circular is to inform Members and Exchange Participants of a change to the Soft Commodity Contract Levies in respect of London Cocoa, Euro Cocoa, London Robusta Coffee, White Sugar, Containerized White Sugar and UK Feed Wheat Futures and Options Contracts (“the Contracts”). The change to the Contracts’ Exchange and Clearing Fees will be effective from Wednesday 02 January 2019. The new fee structure is outlined below. Fees for Futures and Block Contracts and Options Contracts increase to £0.78 per lot per side. Fees for EFP/EFSs and Option Exercise are unchanged. The webpage for the full set of fees for Soft Commodity Products will be updated on Wednesday 02 January 2019 to reflect these changes. CONTRACT LEVIES — LONDON COCOA AND EURO COCOA1 , ROBUSTA FEES (£) COFFEE, WHITE SUGAR AND CONTAINERISED WHITE SUGAR, UK FEED WHEAT EXCHANGE CLEARING TOTAL EFP/EFS 0.09 0.78 0.87 Futures and Block2 Contracts 0.23 0.55 0.78 Options Contracts (including Calendar Spread Options) 0.23 0.55 0.78 Option Exercise (including Calendar Spread Options) 0.00 0.075 0.075 1 London Cocoa and Euro Cocoa — futures exchange and clearing fee is £0.79, with £0.01 per lot per side being paid to support the Cocoa Research Association. 2 Block contract is only applicable to White Sugar Arbitrage, London Cocoa/Euro Cocoa Arbitrage and Robusta Coffee Arbitrage. -

Metals Recovery Offsets Energy Decline

Market Commentary 1 Energy 3 Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM) Metals 5 Agriculture 7 Tables & Charts – February 2017 Edition DATA PERFORMANCE: 11 Overview, Commodity TR, Prices, Volatility Metals Recovery CURVE ANALYSIS: 15 Contango/Backwardation, Roll Yields, Offsets Energy Decline Forwards/Forecasts MARKET FLOWS: 18 Open Interest, Volume, - Up slightly in 2017 as of February, March may set the BCOM tone for 1H COT, ETFs - Narrowing crude oil and U.S. dollar ranges suggest a volatility pick-up soon - Reviving precious metals lead all sectors with industrials close behind, but appearing extended - Grains grind higher anticipating planting and the potential for some production normalization - Energy is largest index drag due to extended positions and plunging natural gas - Strong metals indicate reflation, but industrials outperforming is more favorable economically Mike McGlone – BI Senior Analyst; Commodities. BI COMD (the commodity dashboard) Broad Commodities Mark Time as S&P 500 Is Top Performer in 2017 Gold & Oil Battle for Leadership Performance: February +0.2%, YTD +.3, Spot 2.4%. (returns are total return (TR) unless noted) The Bloomberg Commodity Index, flat in 2017 on a total return basis and up 2.4% spot can be considered reflationary due to strong metals, but may have negative economic implications if precious continue to outperform. Precious metals, due to snap back from 4Q weakness, are up 10.5% in 2017 vs. 9.9% for industrial metals. MACRO OUTLOOK Some reversion of position and price extremes is at play, notably in energy, down 10.1%. Excessive optimism for Industrial Metals Lagging Precious Indicates Similar further energy-price gains accompanied by record open in Yields.