Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (Takım Düzeyinde)

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (TAKIM DÜZEYİNDE) GÖKHAN AYDIN 2016 Editör : Gökhan AYDIN Dizgi : Ziya ÖNCÜ ISBN : 978-605-87432-3-6 Böceklerin Sınıflandırılması isimli eğitim amaçlı hazırlanan bilgisayar programı için lütfen aşağıda verilen linki tıklayarak programı ücretsiz olarak bilgisayarınıza yükleyin. http://atabeymyo.sdu.edu.tr/assets/uploads/sites/76/files/siniflama-05102016.exe Eğitim Amaçlı Bilgisayar Programı ISBN: 978-605-87432-2-9 İçindekiler İçindekiler i Önsöz vi 1. Protura - Coneheads 1 1.1 Özellikleri 1 1.2 Ekonomik Önemi 2 1.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 2 2. Collembola - Springtails 3 2.1 Özellikleri 3 2.2 Ekonomik Önemi 4 2.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 4 3. Thysanura - Silverfish 6 3.1 Özellikleri 6 3.2 Ekonomik Önemi 7 3.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 7 4. Microcoryphia - Bristletails 8 4.1 Özellikleri 8 4.2 Ekonomik Önemi 9 5. Diplura 10 5.1 Özellikleri 10 5.2 Ekonomik Önemi 10 5.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 11 6. Plocoptera – Stoneflies 12 6.1 Özellikleri 12 6.2 Ekonomik Önemi 12 6.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 13 7. Embioptera - webspinners 14 7.1 Özellikleri 15 7.2 Ekonomik Önemi 15 7.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 15 8. Orthoptera–Grasshoppers, Crickets 16 8.1 Özellikleri 16 8.2 Ekonomik Önemi 16 8.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 17 i 9. Phasmida - Walkingsticks 20 9.1 Özellikleri 20 9.2 Ekonomik Önemi 21 9.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 21 10. Dermaptera - Earwigs 23 10.1 Özellikleri 23 10.2 Ekonomik Önemi 24 10.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 24 11. Zoraptera 25 11.1 Özellikleri 25 11.2 Ekonomik Önemi 25 11.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 26 12. -

Wildlife Parasitology in Australia: Past, Present and Future

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Journal of Zoology, 2018, 66, 286–305 Review https://doi.org/10.1071/ZO19017 Wildlife parasitology in Australia: past, present and future David M. Spratt A,C and Ian Beveridge B AAustralian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BVeterinary Clinical Centre, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, University of Melbourne, Werribee, Vic. 3030, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Wildlife parasitology is a highly diverse area of research encompassing many fields including taxonomy, ecology, pathology and epidemiology, and with participants from extremely disparate scientific fields. In addition, the organisms studied are highly dissimilar, ranging from platyhelminths, nematodes and acanthocephalans to insects, arachnids, crustaceans and protists. This review of the parasites of wildlife in Australia highlights the advances made to date, focussing on the work, interests and major findings of researchers over the years and identifies current significant gaps that exist in our understanding. The review is divided into three sections covering protist, helminth and arthropod parasites. The challenge to document the diversity of parasites in Australia continues at a traditional level but the advent of molecular methods has heightened the significance of this issue. Modern methods are providing an avenue for major advances in documenting and restructuring the phylogeny of protistan parasites in particular, while facilitating the recognition of species complexes in helminth taxa previously defined by traditional morphological methods. The life cycles, ecology and general biology of most parasites of wildlife in Australia are extremely poorly understood. While the phylogenetic origins of the Australian vertebrate fauna are complex, so too are the likely origins of their parasites, which do not necessarily mirror those of their hosts. -

A Summary List of Fossil Spiders

A summary list of fossil spiders compiled by Jason A. Dunlop (Berlin), David Penney (Manchester) & Denise Jekel (Berlin) Suggested citation: Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2010. A summary list of fossil spiders. In Platnick, N. I. (ed.) The world spider catalog, version 10.5. American Museum of Natural History, online at http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/index.html Last udated: 10.12.2009 INTRODUCTION Fossil spiders have not been fully cataloged since Bonnet’s Bibliographia Araneorum and are not included in the current Catalog. Since Bonnet’s time there has been considerable progress in our understanding of the spider fossil record and numerous new taxa have been described. As part of a larger project to catalog the diversity of fossil arachnids and their relatives, our aim here is to offer a summary list of the known fossil spiders in their current systematic position; as a first step towards the eventual goal of combining fossil and Recent data within a single arachnological resource. To integrate our data as smoothly as possible with standards used for living spiders, our list follows the names and sequence of families adopted in the Catalog. For this reason some of the family groupings proposed in Wunderlich’s (2004, 2008) monographs of amber and copal spiders are not reflected here, and we encourage the reader to consult these studies for details and alternative opinions. Extinct families have been inserted in the position which we hope best reflects their probable affinities. Genus and species names were compiled from established lists and cross-referenced against the primary literature. -

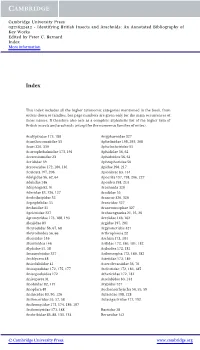

Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: an Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C

Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. Barnard Index More information Index This index includes all the higher taxonomic categories mentioned in the book, from orders down to families, but page numbers are given only for the main occurrences of those names. It therefore also acts as a complete alphabetic list of the higher taxa of British insects and arachnids (except for the numerous families of mites). Acalyptratae 173, 188 Anyphaenidae 327 Acanthosomatidae 55 Aphelinidae 198, 293, 308 Acari 320, 330 Aphelocheiridae 55 Acartophthalmidae 173, 191 Aphididae 56, 62 Acerentomidae 23 Aphidoidea 56, 61 Acrididae 39 Aphrophoridae 56 Acroceridae 172, 180, 181 Apidae 198, 217 Aculeata 197, 206 Apioninae 83, 134 Adelgidae 56, 62, 64 Apocrita 197, 198, 206, 227 Adelidae 146 Apoidea 198, 214 Adephaga 82, 91 Arachnida 320 Aderidae 83, 126, 127 Aradidae 55 Aeolothripidae 52 Araneae 320, 326 Aepophilidae 55 Araneidae 327 Aeshnidae 31 Araneomorphae 327 Agelenidae 327 Archaeognatha 21, 25, 26 Agromyzidae 173, 188, 193 Arctiidae 146, 162 Alexiidae 83 Argidae 197, 201 Aleyrodidae 56, 67, 68 Argyronetidae 327 Aleyrodoidea 56, 66 Arthropleona 22 Alucitidae 146 Aschiza 173, 184 Alucitoidea 146 Asilidae 172, 180, 181, 182 Alydidae 55, 58 Asiloidea 172, 181 Amaurobiidae 327 Asilomorpha 172, 180, 182 Amblycera 48 Asteiidae 173, 189 Anisolabiidae 41 Asterolecaniidae 56, 70 Anisopodidae 172, 175, 177 Atelestidae 172, 183, 185 Anisopodoidea 172 Athericidae 172, 181 Anisoptera 31 Attelabidae 83, 134 Anobiidae 82, 119 Atypidae 327 Anoplura 48 Auchenorrhyncha 54, 55, 59 Anthicidae 83, 90, 126 Aulacidae 198, 228 Anthocoridae 55, 57, 58 Aulacigastridae 173, 192 Anthomyiidae 173, 174, 186, 187 Anthomyzidae 173, 188 Baetidae 28 Anthribidae 83, 88, 133, 134 Beraeidae 142 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. -

Dippenaar MARION.Qxd

The biodiversity and species composition of the spider community of Marion Island, a recent survey (Arachnida: Araneae) T.T. KHOZA, S.M. DIPPENAAR and A.S. DIPPENAAR-SCHOEMAN Khoza, T.T., S.M. Dippenaar and A.S. Dippenaar-Schoeman. 2005. The biodiversity and species composition of the spider community of Marion Island, a recent survey (Arach- nida: Araneae). Koedoe 48(2): 103–107. Pretoria. ISSN 0075-6458. Marion Island, the larger of the Prince Edward Islands, lies in the sub-Antarctic bio- geographic region in the southern Indian Ocean. From previous surveys, four spider species are known from Marion. The last survey was undertaken in 1968. During this study a survey was undertaken over a period of four weeks on the island to determine the present spider diversity and to record information about the habitat preferences and general behaviour of the species present. Three collection methods (active search, Tull- gren funnels and pitfall traps) were used, and spiders were sampled from six habitat sites. A total of 430 spiders represented by four families were collected, Myro kergue- lenesis crozetensis Enderlein, 1909 and M. paucispinosus Berland, 1947 (Desidae), Prinerigone vagans (Audouin, 1826) (Linyphiidae), Cheiracanthium furculatum Karsch, 1879 (Miturgidae) and an immature Salticidae. The miturgid and salticid are first records. Neomaso antarticus (Hickman, 1939) (Linyphiidae) was absent from sam- ples, confirming that the species might have been an erroneous record. Key words: Araneae, biodiversity, Desidae, Linyphiidae, Marion Island, Miturgidae, Salticidae, spiders. T.T. Khoza & S.M. Dippenaar, School of Molecular and Life Sciences, University of Limpopo, Private Bag X1106, Sovenga, 0727 Republic of South Africa; A.S. -

Chewing and Sucking Lice As Parasites of Iviammals and Birds

c.^,y ^r-^ 1 Ag84te DA Chewing and Sucking United States Lice as Parasites of Department of Agriculture IVIammals and Birds Agricultural Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1849 July 1997 0 jc: United States Department of Agriculture Chewing and Sucking Agricultural Research Service Lice as Parasites of Technical Bulletin Number IVIammals and Birds 1849 July 1997 Manning A. Price and O.H. Graham U3DA, National Agrioultur«! Libmry NAL BIdg 10301 Baltimore Blvd Beltsvjlle, MD 20705-2351 Price (deceased) was professor of entomoiogy, Department of Ento- moiogy, Texas A&iVI University, College Station. Graham (retired) was research leader, USDA-ARS Screwworm Research Laboratory, Tuxtia Gutiérrez, Chiapas, Mexico. ABSTRACT Price, Manning A., and O.H. Graham. 1996. Chewing This publication reports research involving pesticides. It and Sucking Lice as Parasites of Mammals and Birds. does not recommend their use or imply that the uses U.S. Department of Agriculture, Technical Bulletin No. discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesti- 1849, 309 pp. cides must be registered by appropriate state or Federal agencies or both before they can be recommended. In all stages of their development, about 2,500 species of chewing lice are parasites of mammals or birds. While supplies last, single copies of this publication More than 500 species of blood-sucking lice attack may be obtained at no cost from Dr. O.H. Graham, only mammals. This publication emphasizes the most USDA-ARS, P.O. Box 969, Mission, TX 78572. Copies frequently seen genera and species of these lice, of this publication may be purchased from the National including geographic distribution, life history, habitats, Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, ecology, host-parasite relationships, and economic Springfield, VA 22161. -

Large Inter- and Intraspecific Variation in Heat Tolerance Across Trophic Levels of a Soil Arthropod Community

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Heated communities Franken, Oscar; Huizinga, Milou; Ellers, Jacintha; Berg, Matty P. Published in: Oecologia DOI: 10.1007/s00442-017-4032-z IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Franken, O., Huizinga, M., Ellers, J., & Berg, M. P. (2018). Heated communities: Large inter- and intraspecific variation in heat tolerance across trophic levels of a soil arthropod community. Oecologia, 186(2), 311-322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-4032-z Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 13-11-2019 Oecologia (2018) 186:311–322 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-4032-z HIGHLIGHTED STUDENT RESEARCH Heated communities: large inter‑ and intraspecifc variation in heat tolerance across trophic levels of a soil arthropod community Oscar Franken1 · Milou Huizinga1 · Jacintha Ellers1 · Matty P. -

Marine Insects

UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography Technical Report Title Marine Insects Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1pm1485b Author Cheng, Lanna Publication Date 1976 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Marine Insects Edited by LannaCheng Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, La Jolla, Calif. 92093, U.S.A. NORTH-HOLLANDPUBLISHINGCOMPANAY, AMSTERDAM- OXFORD AMERICANELSEVIERPUBLISHINGCOMPANY , NEWYORK © North-Holland Publishing Company - 1976 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,without the prior permission of the copyright owner. North-Holland ISBN: 0 7204 0581 5 American Elsevier ISBN: 0444 11213 8 PUBLISHERS: NORTH-HOLLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY - AMSTERDAM NORTH-HOLLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY LTD. - OXFORD SOLEDISTRIBUTORSFORTHEU.S.A.ANDCANADA: AMERICAN ELSEVIER PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC . 52 VANDERBILT AVENUE, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10017 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Marine insects. Includes indexes. 1. Insects, Marine. I. Cheng, Lanna. QL463.M25 595.700902 76-17123 ISBN 0-444-11213-8 Preface In a book of this kind, it would be difficult to achieve a uniform treatment for each of the groups of insects discussed. The contents of each chapter generally reflect the special interests of the contributors. Some have presented a detailed taxonomic review of the families concerned; some have referred the readers to standard taxonomic works, in view of the breadth and complexity of the subject concerned, and have concentrated on ecological or physiological aspects; others have chosen to review insects of a specific set of habitats. -

Nomina Insecta Nearctica Table of Contents

5 NOMINA INSECTA NEARCTICA TABLE OF CONTENTS Generic Index: Dermaptera -------------------------------- 73 Introduction ----------------------------------------------------------------- 9 Species Index: Dermaptera --------------------------------- 74 Structure of the Check List --------------------------------- 11 Diplura ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 77 Original Orthography ---------------------------------------- 13 Classification: Diplura --------------------------------------- 79 Species and Genus Group Name Indices ----------------- 13 Alternative Family Names: Diplura ----------------------- 80 Structure of the database ------------------------------------ 14 Statistics: Diplura -------------------------------------------- 80 Ending Date of the List -------------------------------------- 14 Anajapygidae ------------------------------------------------- 80 Methodology and Quality Control ------------------------ 14 Campodeidae -------------------------------------------------- 80 Classification of the Insecta -------------------------------- 16 Japygidae ------------------------------------------------------ 81 Anoplura -------------------------------------------------------------------- 19 Parajapygidae ------------------------------------------------- 81 Classification: Anoplura ------------------------------------ 21 Procampodeidae ---------------------------------------------- 82 Alternative Family Names: Anoplura --------------------- 22 Generic Index: Diplura -------------------------------------- -

Ectoparasites of the Critically Endangered Insular Cavy, Cavia Intermedia

International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife 4 (2015) 37–42 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijppaw Brief Report Ectoparasites of the critically endangered insular cavy, Cavia intermedia (Rodentia: Caviidae), southern Brazil André Luis Regolin a,*, Nina Furnari b, Fernando de Castro Jacinavicius c, Pedro Marcos Linardi d, Carlos José de Carvalho-Pinto e a Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria 97110-970, Brazil b Departamento de Psicologia Experimental, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo 05508-030, Brazil c Instituto Butantan, São Paulo 05503900, Brazil d Departamento de Parasitologia, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte 31270-901, Brazil e Departamento de Microbiologia e Parasitologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis 88040-900, Brazil ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Cavia intermedia is a rodent species critically endangered and is found only on a 10 hectare island off Received 22 September 2014 the southern Brazilian coast. To identify the ectoparasites of C. intermedia, 27 specimens (14 males and Revised 22 December 2014 13 females), representing approximately 65% of the estimated total population, were captured and ex- Accepted 23 December 2014 amined. A total of 1336 chewing lice of two species were collected: Gliricola lindolphoi (Amblycera: Gyropidae) and Trimenopon hispidum (Amblycera: Trimenoponidae). In addition, chiggers Arisocerus hertigi Keywords: (Acari: Trombiculidae) and Eutrombicula sp. (Acari: Trombiculidae) were collected from the ears of all Chewing lice captured animals. This low species richness compared to those for other Cavia species is expected for Gyropidae Insular syndrome island mammals. -

CATALOG of ENTOMOLOGICAL TYPES in the BISHOP MUSEUM Mallophaga

Pacific Insects Vol. 20, no. 1: 5-17 30 January 1979 CATALOG OF ENTOMOLOGICAL TYPES IN THE BISHOP MUSEUM Mallophaga By JoAnn M. Tenorio1 Abstract: This catalog lists the holotypes of 66 species and allotypes of 18 species of Mallophaga deposited in the Bishop Museum. Locality data are provided, as are corrected or confirmed host identifications, for many ofthe types. The Mallophaga collection in the Bishop Museum contains approximately 500 named species identified by specialists, preserved on some 6000 slides and in alcohol. The actual number of identified specimens is many more than would be indicated by the number of slides because of the practice of mounting a specimen of each sex side by side on the same slide. Much additional material is identified only to generic level. The bulk ofthe collection derives from New Guinea and the Solomons, the Pacific Basin, and the Oriental Region. Particularly extensive collections from New Guinea are still being studied and a large collection of Philippine Mallophaga is virtually unworked. This catalog includes holotypes and allotypes of all species actually or reportedly deposited in the Bishop Museum. The type collection comprises holotypes of 66 species, with allotypes associated with 18 of these. Paratypes are not included herein; the collection houses paratypes of more than 75 species. Approximately 72% ofthe primary types are from New Guinea and the Solomons. The format follows that outlined in the Introduction to the Bishop Museum En tomological Type Catalog by Radovsky et al. (1976). Names are listed as originally published and are entered alphabetically under families, also arranged in alphabetical order. -

Arachnides 88

ARACHNIDES BULLETIN DE TERRARIOPHILIE ET DE RECHERCHES DE L’A.P.C.I. (Association Pour la Connaissance des Invertébrés) 88 2019 Arachnides, 2019, 88 NOUVEAUX TAXA DE SCORPIONS POUR 2018 G. DUPRE Nouveaux genres et nouvelles espèces. BOTHRIURIDAE (5 espèces nouvelles) Brachistosternus gayi Ojanguren-Affilastro, Pizarro-Araya & Ochoa, 2018 (Chili) Brachistosternus philippii Ojanguren-Affilastro, Pizarro-Araya & Ochoa, 2018 (Chili) Brachistosternus misti Ojanguren-Affilastro, Pizarro-Araya & Ochoa, 2018 (Pérou) Brachistosternus contisuyu Ojanguren-Affilastro, Pizarro-Araya & Ochoa, 2018 (Pérou) Brachistosternus anandrovestigia Ojanguren-Affilastro, Pizarro-Araya & Ochoa, 2018 (Pérou) BUTHIDAE (2 genres nouveaux, 41 espèces nouvelles) Anomalobuthus krivotchatskyi Teruel, Kovarik & Fet, 2018 (Ouzbékistan, Kazakhstan) Anomalobuthus lowei Teruel, Kovarik & Fet, 2018 (Kazakhstan) Anomalobuthus pavlovskyi Teruel, Kovarik & Fet, 2018 (Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan) Ananteris kalina Ythier, 2018b (Guyane) Barbaracurus Kovarik, Lowe & St'ahlavsky, 2018a Barbaracurus winklerorum Kovarik, Lowe & St'ahlavsky, 2018a (Oman) Barbaracurus yemenensis Kovarik, Lowe & St'ahlavsky, 2018a (Yémen) Butheolus harrisoni Lowe, 2018 (Oman) Buthus boussaadi Lourenço, Chichi & Sadine, 2018 (Algérie) Compsobuthus air Lourenço & Rossi, 2018 (Niger) Compsobuthus maidensis Kovarik, 2018b (Somaliland) Gint childsi Kovarik, 2018c (Kénya) Gint amoudensis Kovarik, Lowe, Just, Awale, Elmi & St'ahlavsky, 2018 (Somaliland) Gint gubanensis Kovarik, Lowe, Just, Awale, Elmi & St'ahlavsky,