HANDEL OPERA in GERMANY, 1920-1930 Abbey E. Thompson a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert-Lortzing-Gesellschaft E. V. Februar 2009

Info Nr. 8 Albert-Lortzing-Gesellschaft e. V. Februar 2009 Albert-Lortzing-Gesellschaft e. V. gegründet 2001 Lortzings Wohnhaus, die Große Funkenburg, in Leipzig Info Nr. 8 Albert-Lortzing-Gesellschaft e. V. Februar 2009 2 Info Nr. 8 Albert-Lortzing-Gesellschaft e. V. Februar 2009 Liebe Mitglieder, endlich halten Sie wieder einen Rundbrief in den Händen. Ich freue mich, daß auch diesmal zwei Mitglieder unserer Gesellschaft Beiträge verfasst haben, die den wesentlichen Teil dieses Rundbriefes ausmachen. Darüber hinaus finden Sie erneut Original-Rezensionen einiger Aufführungen durch Mitglieder unserer Gesellschaft sowie weitere Informationen, die hoffentlich Ihr Interesse finden. Das wichtigste Ereignis 2009 ist sicherlich das Mitgliedertreffen in Leipzig und die aus diesem Anlass stattfindende Fachtagung der Musikwissenschaftlichen Abteilung der Hochschule für Musik Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Wir danken Herrn Prof. Dr. Schipperges sehr herzlich für die inhaltliche Planung und Organisation dieser Tagung. Ich wünsche allen einen schönen Frühling und freue mich, Sie bei dem Treffen in Leip- zig persönlich begrüßen zu können. Mit herzlichen Grüßen im Namen des ganzen Vorstands Ihre Irmlind Capelle Detmold, Ende Februar 2009 Impressum: Herausgeber: Albert-Lortzing-Gesellschaft e. V. c/o Prof. Dr. Bodo Gotzkowsky, Leipziger Straße 96, D – 36037 Fulda, Tel. 0661 604104 e-Mail: [email protected] Redaktion: Dr. Irmlind Capelle (V.i.S.d.P.) (Namentlich gezeichnete Beiträge müssen nicht unbe- dingt der Meinung des Herausgebers entsprechen.) © Lortzing-Gesellschaft e. V., 2009 Info Nr. 8 Albert-Lortzing-Gesellschaft e. V. Februar 2009 Info Nr. 8 Albert-Lortzing-Gesellschaft e. V. Februar 2009 Rosina Regina Lortzing geb. Ahles Die Suche nach ihrem Grab Ein Bericht von Petra Golbs Regina Rosina (geb. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

94. Bachfest Der Neuen Bachgesellschaft E. V. Sehr Geehrte Damen Und Herren

10.– 19.05.2019 94. Bachfest der Neuen Bachgesellschaft e. V. Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, zum zweiten Mal ist das Bachfest der Neuen Bach- gesellschaft in Rostock zu Gast. Eingebettet in das Doppeljubiläum „800 Jahre Hanse- und Universi- tätsstadt Rostock 2018“ und „600 Jahre Universität Rostock 2019“ wird das Bachfest unter der Schirm- herrschaft der Ministerpräsidentin Manuela Schwe- sig ein Höhepunkt der Jubiläumsfeierlichkeiten sein. Wir freuen uns, dass Bach-Interpreten von Weltrang unserer Einladung gefolgt sind und neben hiesigen Künstlern auftreten: Konzerte mit der Sopranis- tin Dorothee Mields, den beiden Preisträgern der Bach-Medaille Reinhard Goebel und Peter Kooij, den Organisten Ton Koopman und Christoph Schoener, den aus Mitgliedern der Berliner Philharmoniker bestehenden Berliner Barock Solisten, der Lautten Compagney BERLIN und vielen anderen verspre- 3 Vorworte chen ein abwechslungsreiches und hochkarätiges Programm. Eines der Hauptaugenmerke des Festi- 8 Konzerte vals gilt dem Dirigenten und Musikwissenschaftler Hermann Kretzschmar, der in Rostock mit seinen 50 Gottesdienste, Andachten „Historischen Konzerten“ die Grundlage für die regelmäßigen Bachfeste der NBG legte und 1901 in 56 Für Kinder und Familien Berlin das erste Bachfest leitete. In besonderer Wei- se wird der böhmische Komponist Antonín Dvorˇák 62 Lesungen, Tagungen, Vorträge gewürdigt und ich freue mich, dass sein „Requiem“, das „Stabat Mater“, die D-Dur-Messe, die „Biblischen 66 Service Lieder“ und andere Kompositionen zur Auffüh- rung kommen werden. Zudem macht unser Pro- grammkonzept die Bedeutungsvielfalt des Begriffes „Kontrapunkt“ zum Schwerpunkt. Das Fest selbst ist in mehrfacher Hinsicht kontrapunktisch angelegt. Neben den Aufführungen Bach‘scher Vokal- und Instrumentalwerke gehört die Erkundung selten zu hörender Kontrapunkte in das breit gefächerte Pro- gramm. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

The Return of Handel's Giove in Argo

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 1685-1759 Giove in Argo Jupiter in Argos Opera in Three Acts Libretto by Antonio Maria Lucchini First performed at the King’s Theatre, London, 1 May 1739 hwv a14 Reconstructed with additional recitatives by John H. Roberts Arete (Giove) Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani tenor Iside Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Erasto (Osiri) Vito Priante bass Diana Theodora Baka mezzo-soprano Calisto Karina Gauvin soprano Licaone Johannes Weisser baritone IL COMPLESSO BAROCCO Alan Curtis direction 2 Ouverture 1 Largo – Allegro (3:30) 1 2 A tempo di Bourrée (1:29) ATTO PRIMO 3 Coro Care selve, date al cor (2:01) 4 Recitativo: Licaone Imbelli Dei! (0:48) 5 Aria: Licaone Affanno tiranno (3:56) 6 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (3:20) 7 Recitativo: Diana Della gran caccia, o fide (0:45) 8 Aria: Diana Non ingannarmi, cara speranza (7:18) 9 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (1:12) 10 Aria: Iside Deh! m’aiutate, o Dei (2:34) 11 Recitativo: Iside Fra il silenzio di queste ombrose selve (1:01) 12 Arioso: Iside Vieni, vieni, o de’ viventi (1:08) 13 Recitativo: Arete Iside qui, fra dolce sonno immersa? (0:23) 14 Aria: Arete Deh! v’aprite, o luci belle (3:38) 15 Recitativo: Iside, Arete Olà? Chi mi soccorre? (1:39) 16 Aria: Iside Taci, e spera (3:39) 17 Arioso: Calisto Tutta raccolta ancor (2:03) 18 Recitativo: Calisto, Erasto Abbi, pietoso Cielo (1:52) 19 Aria: Calisto Lascia la spina (2:43) 20 Recitativo: Erasto, Arete Credo che quella bella (1:23) 21 Aria: Arete Semplicetto! a donna credi? (6:11) 22 Recitativo: Erasto Che intesi mai? (0:23) 23 Aria: Erasto -

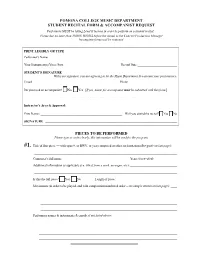

Student Recital/Accompanist Request Form

POMONA COLLEGE MUSIC DEPARTMENT STUDENT RECITAL FORM & ACCOMPANIST REQUEST Performers MUST be taking Level II lessons in order to perform on a student recital. Forms due no later than THREE WEEKS before the recital to the Concert Production Manager Incomplete forms will be returned. PRINT LEGIBLY OR TYPE Performer’s Name:__________________________________________________________________________________ Your Instrument(s)/Voice Part: Recital Date: _________________________ STUDENT’S SIGNATURE _________________________________________________________________________ With your signature, you are agreeing to let the Music Department live-stream your performance. Email _____________________________________________________ Phone ______________________________ Do you need an accompanist? •No •Yes [If yes, music for accompanist must be submitted with this form.] ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Instructor’s Area & Approval: Print Name: ____________________________________________________ Will you attend the recital? •Yes •No SIGNATURE ____________________________________________________________________________________ PIECES TO BE PERFORMED Please type or write clearly, this information will be used for the program. #1. Title of first piece — with opus #, or BWV, or year composed or other such notation (See guide on last page): ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Composer’s full name: _________________________________________ Years (born–died): ______________ -

Stadtarchiv Wuppertal ND 1 Marie-Luise Baum

Stadtarchiv Wuppertal ND 1 Marie-Luise Baum Inhaltsverzeichnis VORWORT .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 KORRESPONDENZEN ........................................................................................................................................... 5 LEBENSDOKUMENTE ......................................................................................................................................... 23 SAMMLUNGEN UND OBJEKTE .......................................................................................................................... 30 WERKE ................................................................................................................................................................. 43 Vorwort Vorwort Marie-Luise Baum, geb. am 21.05.1887 in Hadersleben, gest. am 07.06.1979 in Wuppertal, Bibliothekarin, Eh- renmitglied des Bergischen Geschichtsvereins und Verfasserin biographischer Arbeiten zur Wuppertaler Ge- schichte. Der Nachlass hat einen Umfang von 12 Archivkartons. Korrespondenzen ND 1 Nr. 81 Korrespondenz, Materialien und Beiträge 1790 - 1816; über Carl Aders (1780-1846) und die Familie Aders; (1823 - 1825; Originalbriefe von Angehörigen der Familie Aders 1923); 1938 - Alte Archivsignatur: NDS 1972 1 Karton 12 Nr. 61 Stammbaum von Johann Kaspar Aders; Kor- respondenz vor allem mit Prof. Dr. Hertha Marquardt betr. einen gemeinsamen Beitrag über Carl Aders, mit -

Christopher Ainslie Selected Reviews

Christopher Ainslie Selected Reviews Ligeti Le Grand Macabre (Prince Go-Go), Semperoper Dresden (November 2019) Counter Christopher Ainslie [w]as a wonderfully infantile Prince Go-Go ... [The soloists] master their games as effortlessly as if they were singing Schubertlieder. - Christian Schmidt, Freiepresse A multitude of excellent voices [including] countertenor Christopher Ainslie as Prince with pure, blossoming top notes and exaggerated drama they are all brilliant performances. - Michael Ernst, neue musikzeitung Christopher Ainslie gave a honeyed Prince Go-Go. - Xavier Cester, Ópera Actual Ainslie with his wonderfully extravagant voice. - Thomas Thielemann, IOCO Prince Go-Go, is agile and vocally impressive, performed by Christopher Ainslie. - Björn Kühnicke, Musik in Dresden Christopher Ainslie lends the ruler his extraordinary countertenor voice. - Jens Daniel Schubert, Sächsische Zeitung Christopher Ainslie[ s] rounded countertenor, which carried well into that glorious acoustic. - operatraveller.com Handel Rodelinda (Unulfo), Teatro Municipal, Santiago, Chile (August 2019) Christopher Ainslie was a measured Unulfo. Claudia Ramirez, Culto Latercera Handel Belshazzar (Cyrus), The Grange Festival (June 2019) Christopher Ainslie makes something effective out of the Persian conqueror Cyrus. George Hall, The Stage Counter-tenors James Laing and Christopher Ainslie make their mark as Daniel and Cyrus. Rupert Christiansen, The Telegraph Ch enor is beautiful he presented the conflicted hero with style. Melanie Eskenazi, MusicOMH Christopher Ainslie was impressive as the Persian leader Cyrus this was a subtle exploration of heroism, plumbing the ars as well as expounding his triumphs. Ashutosh Khandekar, Opera Now Christopher Ainslie as a benevolent Cyrus dazzles more for his bravura clinging onto the side of the ziggurat. David Truslove, OperaToday Among the puritanical Persians outside (then inside) the c ot a straightforwardly heroic countertenor but a more subdued, lighter and more anguished reading of the part. -

Raffaele Pe, Countertenor La Lira Di Orfeo

p h o t o © N i c o l a D a l M Raffaele Pe, countertenor a s o ( R Raffaella Lupinacci, mezzo-soprano [track 6] i b a l t a L u c e La Lira di Orfeo S t u d i o Luca Giardini, concertmaster ) ba Recorded in Lodi (Teatro alle Vigne), Italy, in November 2017 Engineered by Paolo Guerini Produced by Diego Cantalupi Music editor: Valentina Anzani Executive producer & editorial director: Carlos Céster Editorial assistance: Mark Wiggins, María Díaz Cover photos of Raffaele Pe: © Nicola Dal Maso (RibaltaLuce Studio) Design: Rosa Tendero © 2018 note 1 music gmbh Warm thanks to Paolo Monacchi (Allegorica) for his invaluable contribution to this project. giulio cesare, a baroque hero giulio cesare, a baroque hero giulio cesare, a baroque hero 5 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo (c165 3- 1723) Sdegnoso turbine 3:02 Opera arias (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , Rome, 1713, I.2; libretto by Antonio Ottoboni) role: Giulio Cesare ba 6 George Frideric Handel Son nata a lagrimar 7:59 (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , London, 1724, I.12; libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym) roles: Sesto and Cornelia 1 George Frideric Handel (168 5- 1759) Va tacito e nascosto 6:34 7 Niccolò Piccinni (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , London, 1724, I.9; libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym) Tergi le belle lagrime 6:36 role: Giulio Cesare (sung in London by Francesco Bernardi, also known as Senesino ) (from Cesare in Egitto , Milan, 1770, I.1; libretto after Giacomo Francesco Bussani) role: Giulio Cesare (sung in Milan by Giuseppe Aprile, also known as Sciroletto ) 2 Francesco Bianchi (175 2- -

Handel Arias

ALICE COOTE THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET HANDEL ARIAS HERCULES·ARIODANTE·ALCINA RADAMISTO·GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL A portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685–1749) 2 CONTENTS TRACK LISTING page 4 ENGLISH page 5 Sung texts and translation page 10 FRANÇAIS page 16 DEUTSCH Seite 20 3 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Radamisto HWV12a (1720) 1 Quando mai, spietata sorte Act 2 Scene 1 .................. [3'08] Alcina HWV34 (1735) 2 Mi lusinga il dolce affetto Act 2 Scene 3 .................... [7'45] 3 Verdi prati Act 2 Scene 12 ................................. [4'50] 4 Stà nell’Ircana Act 3 Scene 3 .............................. [6'00] Hercules HWV60 (1745) 5 There in myrtle shades reclined Act 1 Scene 2 ............. [3'55] 6 Cease, ruler of the day, to rise Act 2 Scene 6 ............... [5'35] 7 Where shall I fly? Act 3 Scene 3 ............................ [6'45] Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 (1724) 8 Cara speme, questo core Act 1 Scene 8 .................... [5'55] Ariodante HWV33 (1735) 9 Con l’ali di costanza Act 1 Scene 8 ......................... [5'42] bl Scherza infida! Act 2 Scene 3 ............................. [11'41] bm Dopo notte Act 3 Scene 9 .................................. [7'15] ALICE COOTE mezzo-soprano THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET conductor 4 Radamisto Handel diplomatically dedicated to King George) is an ‘Since the introduction of Italian operas here our men are adaptation, probably by the Royal Academy’s cellist/house grown insensibly more and more effeminate, and whereas poet Nicola Francesco Haym, of Domenico Lalli’s L’amor they used to go from a good comedy warmed by the fire of tirannico, o Zenobia, based in turn on the play L’amour love and a good tragedy fired with the spirit of glory, they sit tyrannique by Georges de Scudéry. -

Walter Frisch, Ed. Brahms and His World, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990

Document generated on 09/23/2021 8:36 a.m. Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes --> See the erratum for this article Walter Frisch, ed. Brahms and His World, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. 223 pp. ISBN 0-691-09139-0 (cloth), ISBN 0-691-02713-7 (paper) James Deaville Volume 12, Number 1, 1992 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014221ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1014221ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (print) 2291-2436 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Deaville, J. (1992). Review of [Walter Frisch, ed. Brahms and His World, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. 223 pp. ISBN 0-691-09139-0 (cloth), ISBN 0-691-02713-7 (paper)]. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 12(1), 149–154. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014221ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit des universités canadiennes, 1991 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ was not a first language. Descriptive accounts and, even worse, abstract ideas in several papers (especially those by Czechanowska, Reinhard, and Yeh) are unclear, seemingly muddied by the process of translation. -

Jonathan Leif Thomas, Countertenor Dr

The University of North Carolina at Pembroke Department of Music Presents Graduate Lecture Recital Jonathan Leif Thomas, countertenor Dr. Seung-Ah Kim, piano Presentation of Research Findings Jonathan Thomas INTERMISSION Dove sei, amato bene? (from Rodelinda).. George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Ch'io mai vi possa (from Siroe) fl fervido desiderio .Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) Ma rendi pur contento Now sleeps the crimson petal.. .. Roger Quilter (1877-1953) Blow, blow, thou winter wind Pie Jesu (from Requiem) .. Andrew Lloyd Webber Dr. Jaeyoon Kim, tenor (b.1948) THESIS COMMITTEE Dr. Valerie Austin Thesis Advisor Dr. Jaeyoon Kim Studio Professor Dr. Jose Rivera Dr. Katie White This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in Music Education. Jonathan Thomas is a graduate student of Dr. Valerie Austin and studies voice with Dr. Jaeyoon Kim. As a courtesy to the performers and audience, please adjust all mobile devices for no sound and no light. Please enter and exit during applause only. March 27,2014 7:30 PM Moore Hall Auditorium This publication is available in alternative formats upon request. Please contact Disability Support Services, OF Lowry Building, 521.6695. Effective Instructional Strategies for Middle School Choral Teachers: Teaching Middle School Boys to Sing During Vocal Transition UNCP Graduate Lecture Recital Jonathan L. Thomas / Abstract Teaching vocal skills to male students whose voices are transitioning is an undertaking that many middle school choral teachers find challenging. Research suggests that one reason why challenges exist is because of teachers' limited knowledge about the transitioning male voice. The development of self-identity, peer pressure, and the understanding of social norms, which will be associated with psychological transitions for this study, is another factor that creates instructional challenges for choral teachers.