Thesis Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scramble for Land Between the Barokologadi Community and Hermannsburg Missionaries

The Scramble for Land between the Barokologadi Community and Hermannsburg Missionaries Victor MS Molobi https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7824-1048 University of South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article investigates the land claim of the Barokologadi of Melorane, with their long history of disadvantages in the land of their forefathers. The sources of such disadvantages are traceable way back to tribal wars (known as “difaqane”) in South Africa. At first, people were forced to retreat temporarily to a safer site when the wars were in progress. On their return, the Hermannsburg missionaries came to serve in Melorane, benefiting from the land provided by the Kgosi. Later the government of the time expropriated that land. What was the significance of this land? The experience of Melorane was not necessarily unique; it was actually a common practice aimed at acquiring land from rural communities. This article is an attempt to present the facts of that event. There were, however, later interruptions, such as when the Hermannsburg Mission Church became part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Southern Africa (ELCSA). Keywords: land claim; church land; Barokologadi; missionary movement; Hermannsburg; Melorane; Lutheran Introduction Melorane is the area that includes the southern part of Madikwe Game Park in the North West Province, with the village situated inside the park. The community of Melorane is known as the Barokologadi of Maotwe, which was forcibly removed in 1950. Morokologadi is a porcupine, which is a totem of the Barokologadi community. The community received their land back on 6 July 2007 through the National Department of Land Affairs. -

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 1 Table 1: Overview Executive Summary None uploaded. Country Program Strategic Overview Will you be submitting changes to your country's 5-Year Strategy this year? If so, please briefly describe the changes you will be submitting. X Yes No Description: test Ambassador Letter File Name Content Type Date Uploaded Description Uploaded By Letter from Ambassador application/pdf 11/14/2008 TSukalac Nolan.pdf Country Contacts Contact Type First Name Last Name Title Email PEPFAR Coordinator Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] DOD In-Country Contact Chris Wyatt Chief, Office of Security [email protected] Cooperation HHS/CDC In-Country Contact Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] Peace Corps In-Country Peggy McClure Director [email protected] Contact USAID In-Country Contact Joan LaRosa USAID Director [email protected] U.S. Embassy In-Country Phillip Druin DCM [email protected] Contact Global Fund In-Country Batho C Molomo Coordinator of NACA [email protected] Representative Global Fund What is the planned funding for Global Fund Technical Assistance in FY 2009? $0 Does the USG assist GFATM proposal writing? Yes Does the USG participate on the CCM? Yes Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 2 Table 2: Prevention, Care, and Treatment Targets 2.1 Targets for Reporting Period Ending September 30, 2009 National 2-7-10 USG USG Upstream USG Total Target Downstream (Indirect) -

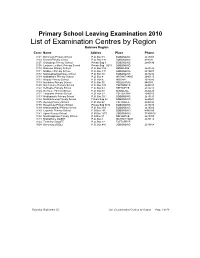

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Kgatleng SUB District

Kgatleng SUB District VOL 5.0 KGATLENG SUB DISTRICT Population and Housing Census 2011 Selected Indicators for Villages and Localities ii i Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 3 Table of Contents Kgatleng Sub District Population And Housing Census 2011: Selected Indicators For Villages And Localities Preface 3 VOL 5,0 1.0 Background and Commentary 6 1.1 Background to the Report 6 Published by 1.2 Importance of the Report 6 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone 2.0 Population Distribution 6 Phone: (267)3671300, 3.0 Population Age Structure 6 Fax: (267) 3952201 Email: [email protected] 3.1 The Youth 7 Website: www.cso.gov.bw/cso 3.2 The Elderly 7 4.0 Annual Growth Rate 7 5.0 Household Size 7 COPYRIGHT RESERVED 6.0 Marital Status 8 7.0 Religion 8 Extracts may be published if source is duly acknowledged 8.0 Disability 9 9.0 Employment and Unemployment 9 10.0 Literacy 10 ISBN: 978-99968-429-7-9 11.0 Orphan-hood 10 12.0 Access to Drinking Water and Sanitation 10 12.1 Access to Portable Water 10 12.2 Access to Sanitation 11 13.0 Energy 11 13.1 Source of Fuel for Heating 11 13.2 Source of Fuel for Lighting 12 13.3 Source of Fuel for Cooking 12 14.0 Projected Population 2011 – 2026 13 Annexes 14 iii Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 1 FIGURE 1: MAP OF KATLENG DISTRICT Preface This report follows our strategic resolve to disaggregate the 2011 Population and Housing Census report, and many of our statistical outputs, to cater for specific data needs of users. -

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief For further details contact Census Office, Private Bag 0024 Gaborone: Tel 3188500; Fax 3188610 1. Botswana Population at 2 Million Botswana’s population has reached the 2 million mark. Preliminary results show that there were 2 038 228 persons enumerated in Botswana during the 2011 Population and Housing Census, compared with 1 680 863 enumerated in 2001. Suffice to note that this is the de-facto population – persons enumerated where they were found during enumeration. 2. General Comments on the Results 2.1 Population Growth The annual population growth rate 1 between 2001 and 2011 is 1.9 percent. This gives further evidence to the effect that Botswana’s population continues to increase at diminishing growth rates. Suffice to note that inter-census annual population growth rates for decennial censuses held from 1971 to 2001 were 4.6, 3.5 and 2.4 percent respectively. A close analysis of the results shows that it has taken 28 years for Botswana’s population to increase by one million. At the current rate and furthermore, with the current conditions 2 prevailing, it would take 23 years for the population to increase by another million - to reach 3 million. Marked differences are visible in district population annual growths, with estimated zero 3 growth for Selebi-Phikwe and Lobatse and a rate of over 4 percent per annum for South East District. Most district growth rates hover around 2 percent per annum. High growth rates in Kweneng and South East Districts have been observed, due largely to very high growth rates of villages within the proximity of Gaborone. -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Botswana. Supervisor of Elections. . Report to the Minister of State on the General Elections, 1974

Botswana. Supervisor of Elections. Report to the Minister of State on the general elections, 1974. Gaborone, Government Printer [1974?] / 30p. 29cm. 1. Botswana-Pol. & govt. 2. Elections- Botswana. I • INDEX Page. Report to the Minister of State on the General Elections, 1974 Evaluation and Recommendations *"* Conclusion ...... 2 - • • • • 4 Title Appendix lA' A list of Constituencies, Polling Districts and Polling Stations showing the number of registered voters by constituency and polling station Appendix '/?' Authenticating Officers appointed in accordance with the Presidential Elections (Supplementary Provisions) Act >;• 12 Appendix 'C A list of Returning Officers for the Parliamentary Elections • ! l 13 Appendix Z)' A list of Returning Officers for the Local Government Elections .. ^ . 14 Appendix 'ZT Summary of the Parliamentary election results Appendix lF 17 A list of candidates in the Parliamentary Election showing the number of votes cast for each, number of votes in each constituency, and the majority gained by the winning can- didate and the percentage poll 18 Appendix '6" Summary of Local Government Election results by District or Town Council 20 Appendix 'IT A list of candidates in the Local Government election showing the number of votes cast tor each, the number of voters in each Polling District, the majority gained by the win- ning candidate, and the percentage poll / 22 Appendix T A list of political Parries registered under Section 149 of the Electoral Act 1969 30 Appendix ' J" A Report on-expenditure on the 1974 General Election 30 Sir, REPORT TO ™E MINISTER. OF STATE ON THE GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1974 SSSITOSSS: S.»=^^HS£s~rr?' Lo^l Government Election* become generally available to the public - - - > »S5S^S^as: • l^^sstsss^aSSSS^5^^-^-"5 5. -

I UNIVERSITY of BOTSWANA FACULTY of AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT of ANIMAL SCIENCE and PRODUCTION MILK PRODUCTION and CAPRINE MASTITIS

UNIVERSITY OF BOTSWANA FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL SCIENCE AND PRODUCTION MILK PRODUCTION AND CAPRINE MASTITIS OCCURANCE IN THE PRODUCTION STAGE OF THE GABORONE REGION GOAT MILK VALUE CHAIN BY WAZHA MUGABE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ANIMAL SCIENCE (ANIMAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS) JUNE 2015 i UNIVERSITY OF BOTSWANA FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL SCIENCE AND PRODUCTION MILK PRODUCTION AND CAPRINE MASTITIS OCCURANCE IN THE PRODUCTION STAGE OF THE GABORONE REGION GOAT MILK VALUE CHAIN BY WAZHA MUGABE A dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Animal Science (Animal Management Systems) Main Supervisor: Dr. G.S. Mpapho Co-Supervisors: Prof. J.M. Kamau Prof. S.J Nsoso Dr. W. Mahabile June 2015 ii ABSTRACT T1he first study was initiated with the objectives of analyzing the production stage of the goat milk value chain and prevalence of caprine mastitis and its impact on the value chain. The study was conducted in the Gaborone agricultural region of Botswana. The primary data was collected using a participatory survey from purposefully selected samples of 91 farmers, 4 traders and 220 consumers through self-administered questionnaires. The results show that 88% of the farmers were subsistence orientated meanwhile semi-commercial and commercial farmers constituted 11% and 1 % respectively. A mean milk yield of 1.18L /goat/ per day was produced across farms and this was mostly channeled towards the 88.6% of non-purchasing consumers for home consumption. The average lactation length in the region was 5.37 months, therefore affecting milk consumption and availability patterns. -

Daily Hansard 14 September 2020

DAILY YOUR VOICE IN PARLIAMENT THETHE SECOND THIRD MEETING MEETING OF THE OF FIRST THE SESSIONFIFTH SESSION OF THE OF THE ELEVENTWELFTH PARLIAMENTTH PARLIAMENT MONDAY 14 SEPTEMBER 2020 ENGLISHMIXED VERSION VERSION HANSARDHANSARD NO. NO: 193 198 DISCLAIMER Unocial Hansard This transcript of Parliamentary proceedings is an unocial version of the Hansard and may contain inaccuracies. It is hereby published for general purposes only. The nal edited version of the Hansard will be published when available and can be obtained from the Assistant Clerk (Editorial). THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP. (Tlokweng) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. -

The Case Study of Botswana Government Thesis

University of Derby Faculty of Business, Law and Computing PhD Racious Moilamashi Moatshe E-government Implementation and Adoption: The Case Study of Botswana Government Thesis Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 1st Supervisor Prof: Nikos Antonopoulos 2nd Supervisor Prof: Keith Horton October 2014 © Racious Moilamashi Moatshe, University of Derby 2014, All rights reserved 1 ABSTRACT The advancements in the ICT and internet technologies challenge governments to engage in the electronic transformation of public services and information provision to citizens. The capability to reach citizens in the physical world via e-government platform and render a citizen-centric public sector has increasingly become vital. Thus, spending more resources to promote and ensure that all members of society are included in the entire spectrum of information society and more actively access government online is a critical aspect in establishing a successful e-government project. Every e-government programme requires a clear idea of the proposed benefits to citizens, the challenges to overcome and the level of institutional reform that has to take place for e- government to be a success in a given context. E- government strategy is fundamental to transforming and modernising the public sector through identification of key influential elements or strategy factors and ways of interacting with citizens. It is therefore apparent that governments must first understand variables that influence citizens’ adoption of e-government in order to take them into account when developing and delivering services online. Botswana has recently embarked on e-government implementation initiatives that started with the e-readiness assessment conducted in 2004, followed by enactment of the National ICT policy of 2007 and the approval of the e-government strategy approved in 2012 for dedicated implementation in the 2014 financial year. -

CUSTOMARY COURTS (INCREASE of CRIMINAL JURISDICTION) ORDER, 1983 (Published on 16Th September, 1983)

Statutory Instrument No. 118 of 1983 CUSTOMARY COURTS ACT (Cap. 04:05) CUSTOMARY COURTS (INCREASE OF CRIMINAL JURISDICTION) ORDER, 1983 (Published on 16th September, 1983) ARRANGEMENT OF PARAGRAPHS PARAGRAPH 1. Citation 2. Increase of criminal jurisdiction of Customary Courts 3. Revocation of S.I. No. 68 of 1972 FIRST SCHEDULE SECOND SCHEDULE IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred on the President by section 11 (5) of the Customary Courts Act, the following Order is hereby made:- 1. This Order may be cited as the Customary Courts (Increase of Criminal Jurisdiction), Order, 1983. 2. The jurisdiction in criminal matters of each of the customary Increase erf courts specified in the first column of the First Schedule hereto, under criminal the district within which it has been recognised or established and within the area specified in the corresponding entry in the second courts։°inary column hereto, shall be that indicated by letters in the corresponding entry in the third column of the said Schedule, which letters refer to the maximum fines or sentences of imprisonment which may be imposed by the court and which are more fully indicated in the Second Schedule hereto. 3 . The provisions relating to punishment for rrini'rig1 Revocation contained in Kecogmtion and ustanushmenf of Customary ....Cpuru o f SJ. Notice, 1972, are hereby revoked. ' 68 oi 1972 FIRST SCHEDULE First Column Second Column Third Column Customary Court Area Criminal Jurisdiction Ngwato Tribal Authority Bangwato E Tribal Territory Senior Sub-Tribal Serowe F Authority Mahalapye