A Source Analysis of the Ruijing Lu ("Records of Miraculous Scriptures"), by Koichi Shinohara 73 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kasāya Robe of the Past Buddha Kāśyapa in the Miraculous Instruction Given to the Vinaya Master Daoxuan (596~667)

中華佛學學報第 13.2 期 (pp.299-367): (民國 89 年), 臺北:中華佛學研究所,http://www.chibs.edu.tw Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal, No. 13.2, (2000) Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies ISSN: 1017-7132 The Kasāya Robe of the Past Buddha Kāśyapa in the Miraculous Instruction Given to the Vinaya Master Daoxuan (596~667) Koichi Shinohara Professor, McMaster University Summary Toward the end of his life, in the second month of the year 667, the eminent vinaya master Daoxuan (596~667) had a visionary experience in which gods appeared to him and instructed him. The contents of this divine teaching are reproduced in several works, such as the Daoxuan lüshi gantonglu and the Zhong Tianzhu Sheweiguo Zhihuansi tujing. The Fayuan zhulin, compiled by Daoxuan's collaborator Daoshi, also preserves several passages, not paralleled in these works, but said to be part of Daoxuan's visionary instructions. These passages appear to have been taken from another record of this same event, titled Daoxuan lüshi zhuchi ganying ji. The Fayuan zhulin was completed in 668, only several months after Daoxuan's death. The Daoxuan lüshi zhuchi ganying ji, from which the various Fayuan zhulin passages on Daoxuan's exchanges with deities were taken, must have been compiled some time between the second lunar month in 667 and the third month in the following year. The quotations in the Fayuan zhulin from the Daoxuan lüshi zhuchi ganying ji take the form of newly revealed sermons of the Buddha and tell stories about various objects used by the Buddha during his life time. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

A Distant Mirror. Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century

Index pp. 535–565 in: Chen-kuo Lin / Michael Radich (eds.) A Distant Mirror Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century Chinese Buddhism Hamburg Buddhist Studies, 3 Hamburg: Hamburg University Press 2014 Imprint Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (German National Library). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. The online version is available online for free on the website of Hamburg University Press (open access). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek stores this online publication on its Archive Server. The Archive Server is part of the deposit system for long-term availability of digital publications. Available open access in the Internet at: Hamburg University Press – http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de Persistent URL: http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de/purl/HamburgUP_HBS03_LinRadich URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-3-1467 Archive Server of the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek – http://dnb.d-nb.de ISBN 978-3-943423-19-8 (print) ISSN 2190-6769 (print) © 2014 Hamburg University Press, Publishing house of the Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Germany Printing house: Elbe-Werkstätten GmbH, Hamburg, Germany http://www.elbe-werkstaetten.de/ Cover design: Julia Wrage, Hamburg Contents Foreword 9 Michael Zimmermann Acknowledgements 13 Introduction 15 Michael Radich and Chen-kuo Lin Chinese Translations of Pratyakṣa 33 Funayama Toru -

The University of Chicago Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology A

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRACTICES OF SCRIPTURAL ECONOMY: COMPILING AND COPYING A SEVENTH-CENTURY CHINESE BUDDHIST ANTHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVINITY SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ALEXANDER ONG HSU CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2018 © Copyright by Alexander Ong Hsu, 2018. All rights reserved. Dissertation Abstract: Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology By Alexander Ong Hsu This dissertation reads a seventh-century Chinese Buddhist anthology to examine how medieval Chinese Buddhists practiced reducing and reorganizing their voluminous scriptural tra- dition into more useful formats. The anthology, A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma (Fayuan zhulin ), was compiled by a scholar-monk named Daoshi (?–683) from hundreds of Buddhist scriptures and other religious writings, listing thousands of quotations un- der a system of one-hundred category-chapters. This dissertation shows how A Grove of Pearls was designed by and for scriptural economy: it facilitated and was facilitated by traditions of categorizing, excerpting, and collecting units of scripture. Anthologies like A Grove of Pearls selectively copied the forms and contents of earlier Buddhist anthologies, catalogs, and other compilations; and, in turn, later Buddhists would selectively copy from it in order to spread the Buddhist dharma. I read anthologies not merely to describe their contents but to show what their compilers and copyists thought they were doing when they made and used them. A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma has often been read as an example of a Buddhist leishu , or “Chinese encyclopedia.” But the work’s precursors from the sixth cen- tury do not all fit neatly into this genre because they do not all use lei or categories consist- ently, nor do they all have encyclopedic breadth like A Grove of Pearls. -

The Mongolian Big Dipper Sūtra

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 29 Number 1 2006 (2008) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. It welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. EDITORIAL BOARD JIABS is published twice yearly, in the summer and winter. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: Joint Editors [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, BUSWELL Robert in two different formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- CHEN Jinhua Document-Format (created e.g. by Open COLLINS Steven Office). COX Collet GÓMEZ Luis O. Address books for review to: HARRISON Paul JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur - und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- VON HINÜBER Oskar Strasse 8-10, AT-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA JACKSON Roger JAINI Padmanabh S. Address subscription orders and dues, KATSURA Shōryū changes of address, and UO business correspondence K Li-ying (including advertising orders) to: LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer MACDONALD Alexander Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Anthropole SEYFORT RUEGG David University of Lausanne CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland SHARF Robert email: [email protected] STEINKELLNER Ernst Web: www.iabsinfo.net TILLEMANS Tom Fax: +41 21 692 30 45 ZÜRCHER Erik Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

APA NEWSLETTER on Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies SPRING 2020 VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 FROM THE GUEST EDITOR Ben Hammer The Timeliness of Translating Chinese Philosophy: An Introduction to the APA Newsletter Special Issue on Translating Chinese Philosophy ARTICLES Roger T. Ames Preparing a New Sourcebook in Classical Confucian Philosophy Tian Chenshan The Impossibility of Literal Translation of Chinese Philosophical Texts into English Dimitra Amarantidou, Daniel Sarafinas, and Paul J. D’Ambrosio Translating Today’s Chinese Masters Edward L. Shaughnessy Three Thoughts on Translating Classical Chinese Philosophical Texts Carl Gene Fordham Introducing Premodern Text Translation: A New Field at the Crossroads of Sinology and Translation Studies SUBMISSION GUIDELINES AND INFORMATION VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 SPRING 2020 © 2020 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies BEN HAMMER, GUEST EDITOR VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2020 Since most of us reading this newsletter have at least a FROM THE GUEST EDITOR vague idea of what Western philosophy is, we must understand that to then learn Chinese philosophy is truly The Timeliness of Translating Chinese to reinvent the wheel. It is necessary to start from the most basic notions of what philosophy is to be able to understand Philosophy: An Introduction to the APA what Chinese philosophy is. Newsletter Special Issue on Translating In the West, religion is religion and philosophy is Chinese Philosophy philosophy. In China, this line does not exist. For China and its close East Asian neighbors, Confucianism has guided Ben Hammer the social and spiritual lives of people for thousands of EDITOR, JOURNAL OF CHINESE HUMANITIES years in the same way the Judeo-Christian tradition has [email protected] guided people in the West. -

Epilogue the Aftermath and the Romanticization of the Liang

epilogue The Aftermath and the Romanticization of the Liang With the Hou Jing Rebellion and the fall of the Liang, the cultural world of the Southern Dynasties came to an end—the Chen was but a fading echo of the Liang. But if the Liang officially ended in 557, its life contin- ued long afterward, both politically and culturally. After the sacking of Jiangling in 555, the Western Wei set up Xiao Cha 蕭詧, Xiao Tong’s third son, as the new ruler of Liang; his territory was limited to Jingzhou and sandwiched between the Western Wei, the Eastern Wei, and the Chen. Although subordinated to the Western Wei, Xiao Cha neverthe- less ruled over the small portion of land as emperor, and his dynasty is known as the Latter Liang 後梁. It lasted thirty-three years, almost as long as the Liang itself. Xiao Cha died at the age of forty-three in 562 and received the posthumous title, Emperor Xuan 宣帝. The throne passed to his third son, Xiao Kui 蕭巋, Emperor Ming 明帝. In 582 Xiao Kui’s daughter was chosen to be the consort of the Sui prince Yang Guang 楊廣, better known as Emperor Yang of the Sui or Sui Yangdi 隋煬帝 (r. 605–17). Emperor Wen of the Sui treated Xiao Kui with exceptional generosity; at the suggestion of his wife, Em- press Yang, he even dismissed the Sui army stationed in the Western City of Jiangling. He also told Xiao Kui that he would conquer the Chen and escort Xiao Kui back to Jiankang. -

Beyond Buddhist Apology the Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Beyond Buddhist Apology The Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty (r.502-549) Tom De Rauw ii To my daughter Pauline, the most wonderful distraction one could ever wish for and to my grandfather, a cakravartin who ruled his own private universe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although the writing of a doctoral dissertation is an individual endeavour in nature, it certainly does not come about from the efforts of one individual alone. The present dissertation owes much of its existence to the help of the many people who have guided my research over the years. My heartfelt thanks, first of all, go to Dr. Ann Heirman, who supervised this thesis. Her patient guidance has been of invaluable help. Thanks also to Dr. Bart Dessein and Dr. Christophe Vielle for their help in steering this thesis in the right direction. I also thank Dr. Chen Jinhua, Dr. Andreas Janousch and Dr. Thomas Jansen for providing me with some of their research and for sharing their insights with me. My fellow students Dr. Mathieu Torck, Leslie De Vries, Mieke Matthyssen, Silke Geffcken, Evelien Vandenhaute, Esther Guggenmos, Gudrun Pinte and all my good friends who have lent me their listening ears, and have given steady support and encouragement. To my wife, who has had to endure an often absent-minded husband during these first years of marriage, I acknowledge a huge debt of gratitude. She was my mentor in all but the academic aspects of this thesis. -

The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan

THE HISTORY OF GYALTHANG UNDER CHINESE RULE: MEMORY, IDENTITY, AND CONTESTED CONTROL IN A TIBETAN REGION OF NORTHWEST YUNNAN Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Michael Tsin Michelle T. King Ralph A. Litzinger W. Miles Fletcher Donald M. Reid © 2016 Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii! ! ABSTRACT Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen: The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan (Under the direction of Michael Tsin) This dissertation analyzes how the Chinese Communist Party attempted to politically, economically, and culturally integrate Gyalthang (Zhongdian/Shangri-la), a predominately ethnically Tibetan county in Yunnan Province, into the People’s Republic of China. Drawing from county and prefectural gazetteers, unpublished Party histories of the area, and interviews conducted with Gyalthang residents, this study argues that Tibetans participated in Communist Party campaigns in Gyalthang in the 1950s and 1960s for a variety of ideological, social, and personal reasons. The ways that Tibetans responded to revolutionary activists’ calls for political action shed light on the difficult decisions they made under particularly complex and coercive conditions. Political calculations, revolutionary ideology, youthful enthusiasm, fear, and mob mentality all played roles in motivating Tibetan participants in Mao-era campaigns. The diversity of these Tibetan experiences and the extent of local involvement in state-sponsored attacks on religious leaders and institutions in Gyalthang during the Cultural Revolution have been largely left out of the historiographical record. -

Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Gregory Adam Scott All Rights Reserved This work may be used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. For more information about that license, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. For other uses, please contact the author. ABSTRACT Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China 經典佛化: 民國初期佛教出版文化 Gregory Adam Scott 史瑞戈 In this dissertation I argue that print culture acted as a catalyst for change among Buddhists in modern China. Through examining major publication institutions, publishing projects, and their managers and contributors from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s, I show that the expansion of the scope and variety of printed works, as well as new the social structures surrounding publishing, substantially impacted the activity of Chinese Buddhists. In doing so I hope to contribute to ongoing discussions of the ‘revival’ of Chinese Buddhism in the modern period, and demonstrate that publishing, propelled by new print technologies and new forms of social organization, was a key field of interaction and communication for religious actors during this era, one that helped make possible the introduction and adoption of new forms of religious thought and practice. 本論文的論點是出版文化在近代中國佛教人物之中,扮演了變化觸媒的角色. 通過研究從十 九世紀末到二十世紀二十年代的主要的出版機構, 種類, 及其主辦人物與提供貢獻者, 論文 說明佛教印刷的多元化 以及範圍的大量擴展, 再加上跟出版有關的社會結構, 對中國佛教 人物的活動都發生了顯著的影響. 此研究顯示在被新印刷技術與新形式的社會結構的推進 下的出版事業, 為該時代的宗教人物展開一種新的相互連結與構通的場域, 因而使新的宗教 思想與實踐的引入成為可能. 此論文試圖對現行關於近代中國佛教的所謂'復興'的討論提出 貢獻. Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables iii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations and Conventions ix Works Cited by Abbreviation x Maps of Principle Locations xi Introduction Print Culture and Religion in Modern China 1. -

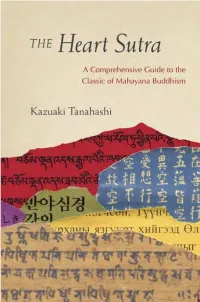

The Heart Sutra in Its Primarily Chinese and Japanese Contexts Covers a Wide Range of Approaches to This Most Famous of All Mahayana Sutras

“Tanahashi’s book on the Heart Sutra in its primarily Chinese and Japanese contexts covers a wide range of approaches to this most famous of all mahayana sutras. It brings the sutra to life through shedding light on it from many different angles, through presenting its historical background and traditional commentaries, evaluating modern scholarship, adapting the text to a contemporary readership, exploring its relationship to Western science, and relating personal anecdotes. The rich- ness of the Heart Sutra and the many ways in which it can be understood and contemplated are further highlighted by his comparison of its versions in the major Asian languages in which it has been transmitted, as well as in a number of English translations. Highly recommended for all who wish to explore the profundity of this text in all its facets.” — Karl Brunnhölzl, author of The Heart Attack Sutra: A New Commentary on the Heart Sutra “A masterwork of loving and meticulous scholarship, Kaz Tanahashi’s Heart Sutra is a living, breathing, deeply personal celebration of a beloved text, which all readers—Buddhists and non-Buddhists, newcomers to the teaching and seasoned scholars alike—will cherish throughout time.” — Ruth Ozeki, author of A Tale for the Time Being Heart Sutra_3rd pass_revIndex.indd 1 10/22/14 1:14 PM Also by Kazuaki Tanahashi Beyond Thinking: A Guide to Zen Meditation Enlightenment Unfolds: The Essential Teachings of Zen Master Dogen The Essential Dogen (with Peter Levitt) Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen’s Shobo Genzo Heart Sutra_3rd pass_revIndex.indd 2 10/22/14 1:14 PM THE Heart Sutra A Comprehensive Guide to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism Kazuaki Tanahashi Shambhala Boston & London 2014 Heart Sutra_3rd pass_revIndex.indd 3 10/22/14 1:14 PM Shambhala Publications, Inc. -

Xuanzang's Relationship to the Heart Sūtra in Light of the Fangshan Stele

Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies (2019, 32: 1–30) New Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies 中華佛學學報 第三十二期 頁 1–30(民國一百零八年)新北:中華佛學研究所 ISSN: 2313-2000 e-ISSN: 2313-2019 Xuanzang’s Relationship to the Heart Sūtra in Light of the Fangshan Stele Jayarava Attwood Independent Scholar, Cambridge, United Kingdom Abstract A transcription of the Fangshan Stele of the Heart Sūtra is presented in an English language Buddhism Studies context for the first time. While the text of this Heart Sūtra is relatively unremarkable, the colophon reveals that work on the stele commenced in 661 CE. This is not only the earliest dated reference to the Heart Sūtra in any language, but the date falls during Xuanzang’s 玄奘 lifetime (ca. 602–664). The status of the Heart Sūtra as an authentic Indian sūtra rests almost entirely on the supposed historical relationship with Xuanzang since it fails to meet the standard criteria for being a sūtra. The historical connection between Xuanzang and the Heart Sūtra is critically re-evaluated in the light of the Fangshan Stele and recent scholarship from the fields of history, philology, and bibliography. Keywords: Heart Sūtra, Xinjing, Prajñāpāramitā, Xuanzang, Fangshan Stele I thank Ji Yun for drawing my attention to the existence of the Fangshan Stele in June 2018. In writing this article I benefitted greatly from my correspondence with Jeffery Kotyk, especially in the area of Chinese historiography. He also made many useful comments on the first draft generally. Another friend, who wishes to remain anonymous, helped me to decipher the colophon and spotted many typos in Chinese.