Études Irlandaises, 41-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Failure of an Irish Political Party

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service 1 Journalism in Ireland: The Evolution of a Discipline Mark O’Brien While journalism in Ireland had a long gestation, the issues that today’s journalists grapple with are very much the same that their predecessors had to deal with. The pressures of deadlines and news gathering, the reliability and protection of sources, dealing with patronage and pressure from the State, advertisers and prominent personalities, and the fear of libel and State regulation were just as much a part of early journalism as they are today. What distinguished early journalism was the intermittent nature of publication and the rapidity with which newspaper titles appeared and disappeared. The Irish press had a faltering start but by the early 1800s some of the defining characteristics of contemporary journalism – specific skill sets, shared professional norms and professional solidarity – had emerged. In his pioneering work on the history of Irish newspapers, Robert Munter noted that, although the first newspaper printed in Ireland, The Irish Monthly Mercury (which carried accounts of Oliver Cromwell’s campaign in Ireland) appeared in December 1649 it was not until February 1659 that the first Irish newspaper appeared. An Account of the Chief Occurrences of Ireland, Together with some Particulars from England had a regular publication schedule (it was a weekly that published at least five editions), appeared under a constant name and was aimed at an Irish, rather than a British, readership. It, in turn, was followed in January 1663 by Mercurius Hibernicus, which carried such innovations as issue numbers and advertising. -

Canada's Periodical on Refugees

Volume 28 Refuge Number 2 Welcome to Ireland: Seeking Protection as an Asylum Seeker or through Resettlement—Different Avenues, Different Reception Louise Kinlen Abstract contexte de l’accueil des réfugiés en Irlande, les conditions Ireland accepts approximately 200 resettled refugees each actuelles d’accueil des deux groupes et leurs diff érences, et year under the UNHCR Resettlement Programme and a examine si ces conditions d’accueil sont justifi ées. range of supports are put in place to assist the refugees when they arrive and to help their process of integration Introduction into Irish society. Roughly ten times this number of asylum- Th e vast majority of refugees in Ireland begin as an asylum seeker in which they individually seek to have their claim seekers arrives in Ireland each year, with some coming from for asylum recognized under the 1951 Convention Relating similar regions and groups as the resettled refugees. Th e to the Status of Refugees (Geneva Convention). If such a reception conditions of both groups however are remark- claim is not recognized at fi rst instance, they may under ably diff erent, with a number of grave humanitarian con- certain circumstances apply for subsidiary protection or cerns having been raised about the reception conditions for leave to remain on humanitarian grounds, granted on of asylum seekers. Th is article explores the background to Ministerial discretion. Whilst one of three forms of resi- refugee reception in Ireland, the current reception condi- dency may ultimately be granted, for the purpose of this tions of the two groups, how they diff er and an analysis of paper, this group is referred to as ‘asylum seekers’. -

Annual Report Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 Annual Report 2017 Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 ISBN: 978-1-904291-57-2

annual report tuarascáil bhliantúil 2017 Annual Report 2017 Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 ISBN: 978-1-904291-57-2 The Arts Council t +353 1 618 0200 70 Merrion Square, f +353 1 676 1302 Dublin 2, D02 NY52 Ireland Callsave 1890 392 492 An Chomhairle Ealaíon www.facebook.com/artscouncilireland 70 Cearnóg Mhuirfean, twitter.com/artscouncil_ie Baile Átha Cliath 2, D02 NY52 Éire www.artscouncil.ie Trophy part-exhibition, part-performance at Barnardo Square, Dublin Fringe Festival. September 2017. Photographer: Tamara Him. taispeántas ealaíne Trophy, taibhiú páirte ag Barnardo Square, Féile Imeallach Bhaile Átha Cliath. Meán Fómhair 2017. Grianghrafadóir: Tamara Him. Body Language, David Bolger & Christopher Ash, CoisCéim Dance Theatre at RHA Gallery. November/December 2017 Photographer: Christopher Ash. Body Language, David Bolger & Christopher Ash, Amharclann Rince CoisCéim ag Gailearaí an Acadaimh Ibeirnigh Ríoga. Samhain/Nollaig 2017 Grianghrafadóir: Christopher Ash. The Arts Council An Chomhairle Ealaíon Who we are and what we do Ár ról agus ár gcuid oibre The Arts Council is the Irish government agency for Is í an Chomhairle Ealaíon an ghníomhaireacht a cheap developing the arts. We work in partnership with artists, Rialtas na hÉireann chun na healaíona a fhorbairt. arts organisations, public policy makers and others to build Oibrímid i gcomhpháirt le healaíontóirí, le heagraíochtaí a central place for the arts in Irish life. ealaíon, le lucht déanta beartas poiblí agus le daoine eile chun áit lárnach a chruthú do na healaíona i saol na We provide financial assistance to artists, arts organisations, hÉireann. local authorities and others for artistic purposes. We offer assistance and information on the arts to government and Tugaimid cúnamh airgeadais d'ealaíontóirí, d'eagraíochtaí to a wide range of individuals and organisations. -

2014–2015 Season Sponsors

2014–2015 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2014–2015 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following current CCPA Associates donors who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue where patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. MARQUEE Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Diana and Rick Needham Eleanor and David St. Clair Mr. and Mrs. Curtis R. Eakin A.J. Neiman Judy and Robert Fisher Wendy and Mike Nelson Sharon Kei Frank Jill and Michael Nishida ENCORE Eugenie Gargiulo Margene and Chuck Norton The Gettys Family Gayle Garrity In Memory of Michael Garrity Ann and Clarence Ohara Art Segal In Memory Of Marilynn Segal Franz Gerich Bonnie Jo Panagos Triangle Distributing Company Margarita and Robert Gomez Minna and Frank Patterson Yamaha Corporation of America Raejean C. Goodrich Carl B. Pearlston Beryl and Graham Gosling Marilyn and Jim Peters HEADLINER Timothy Gower Gwen and Gerry Pruitt Nancy and Nick Baker Alvena and Richard Graham Mr. -

Papers of Gemma Hussey P179 Ucd Archives

PAPERS OF GEMMA HUSSEY P179 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 © 2016 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History vi CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vii System of Arrangement ix CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access xi Language xi Finding Aid xi DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note xi ALLIED MATERIALS Allied Collections in UCD Archives xi Published Material xi iii CONTEXT Biographical History Gemma Hussey nee Moran was born on 11 November 1938. She grew up in Bray, Co. Wicklow and was educated at the local Loreto school and by the Sacred Heart nuns in Mount Anville, Goatstown, Co. Dublin. She obtained an arts degree from University College Dublin and went on to run a successful language school along with her business partner Maureen Concannon from 1963 to 1974. She is married to Dermot (Derry) Hussey and has one son and two daughters. Gemma Hussey has a strong interest in arts and culture and in 1974 she was appointed to the board of the Abbey Theatre serving as a director until 1978. As a director Gemma Hussey was involved in the development of policy for the theatre as well as attending performances and reviewing scripts submitted by playwrights. In 1977 she became one of the directors of TEAM, (the Irish Theatre in Education Group) an initiative that emerged from the Young Abbey in September 1975 and founded by Joe Dowling. It was aimed at bringing theatre and theatre performance into the lives of children and young adults. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 1005 Thursday, No. 2 11 March 2021 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Covid-19 Vaccination Programme: Statements � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 148 Ceisteanna ó Cheannairí - Leaders’ Questions � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 176 11/03/2021Q00500Ceisteanna ar Reachtaíocht a Gealladh - Questions on Promised Legislation � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 184 11/03/2021T02475Statement by An Taoiseach� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 193 11/03/2021U01200Petroleum and Other Minerals Development (Amendment) (Climate Emergency Measures) Bill 2018: Referral to Select Committee � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 195 11/03/2021U01700An Bille um Cheathrú Chultúir 1916, 2021: First Stage � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 196 11/03/2021W00100Criminal Justice (Theft and Fraud Offences) (Amendment) Bill 2020 [Seanad]: Order for Report Stage� � � � 197 11/03/2021W00400Criminal Justice (Theft and Fraud Offences) (Amendment) Bill 2020 [Seanad]: Report and Final Stages � � � 198 11/03/2021W01600Criminal Procedure Bill 2021: Order for Report Stage � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 199 11/03/2021W01900Criminal Procedure -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Zarah Bellefroid Corpus Qualitative Analysis

THE IMPACT OF BREXIT ON NORTHERN IRELAND A FRAMING ANALYSIS OF SPEECHES AND STATEMENTS BY NORTHERN IRISH POLITICIANS Aantal woorden: 17 544 Zarah Bellefroid Studentennummer: 01302366 Promotor(en): Dhr. David Chan Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad master in de Meertalige Communicatie: Nederlands, Engels, Frans Academiejaar: 2017 – 2018 THE IMPACT OF BREXIT ON NORTHERN IRELAND A FRAMING ANALYSIS OF SPEECHES AND STATEMENTS BY NORTHERN IRISH POLITICIANS Aantal woorden: 17 544 Zarah Bellefroid Studentennummer: 01302366 Promotor(en): Dhr. David Chan Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad master in de Meertalige Communicatie: Nederlands, Engels, Frans Academiejaar: 2017 – 2018 1 Verklaring i.v.m. auteursrecht De auteur en de promotor(en) geven de toelating deze studie als geheel voor consultatie beschikbaar te stellen voor persoonlijk gebruik. Elk ander gebruik valt onder de beperkingen van het auteursrecht, in het bijzonder met betrekking tot de verplichting de bron uitdrukkelijk te vermelden bij het aanhalen van gegevens uit deze studie. 2 Acknowledgements This master’s thesis marks the culmination of my academic journey at the University of Ghent, Department of Translation, Interpreting and Communication. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the people who have helped me create this dissertation. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my promotor Mr. Chan. His excellent guidance and encouragement throughout this writing process were of inestimable value. I am thankful for his useful feedback which gave me new insights and enabled me to look at my thesis from a different perspective. Moreover, Mr. Chan taught me the importance of being critical of your own work. -

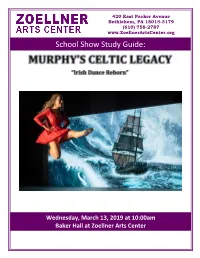

School Show Study Guide

420 East Packer Avenue Bethlehem, PA 18015-3179 (610) 758-2787 www.ZoellnerArtsCenter.org School Show Study Guide: Wednesday, March 13, 2019 at 10:00am Baker Hall at Zoellner Arts Center USING THIS STUDY GUIDE Dear Educator, On Wednesday, March 13, your class will attend a performance by Murphy’s Celtic Legacy, at Lehigh University’s Zoellner Arts Center in Baker Hall. You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Zoellner Arts Center field trip. Materials in this guide include information about the performance, what you need to know about coming to a show at Zoellner Arts Center and interesting and engaging activities to use in your classroom prior to and following the performance. These activities are designed to go beyond the performance and connect the arts to other disciplines and skills including: Dance Culture Expression Social Sciences Teamwork Choreography Before attending the performance, we encourage you to: Review the Know before You Go items on page 3 and Terms to Know on pages 9. Learn About the Show on pages 4. Help your students understand Ireland on pages 11, the Irish dance on pages 17 and St. Patrick’s Day on pages 23. Engage your class the activity on pages 25. At the performance, we encourage you to: Encourage your students to stay focused on the performance. Encourage your students to make connections with what they already know about rhythm, music, and Irish culture. Ask students to observe how various show components, like costumes, lights, and sound impact their experience at the theatre. After the show, we encourage you to: Look through this study guide for activities, resources and integrated projects to use in your classroom. -

222 1 Remembering the Famine

NOTES 1 Remembering the Famine 1. Speech by the Minister of State, Avril Doyle TD, Famine Commemoration Programme, 27 June 1995. 2. The text of a message from the British Prime Minister, Mr Tony Blair, delivered by Britain’s Ambassador to the Republic of Ireland, Veronica Sutherland, on Saturday 31 May 1997 at the Great Irish Famine Event, in Cork (British Information Services, 212). 3. Irish News, 4 February 1997. 4. The designation of the event is contested; some nationalists find the use of the word ‘famine’ offensive and inappropriate given the large amounts of food exported from Ireland. For more on the debate, see Kinealy, A Death-Dealing Famine: The Great Hunger in Ireland (Pluto Press, 1997), Chapter 1. 5. The Irish Times, 3 June 1995. 6. The most influential work which laid the ground for much subsequent revisionist writing was R. D. Crotty, Irish Agricultural Production (Cork University Press, 1996). 7. The most polished and widely read exposition of the revisionist interpretation was provided in Roy Foster, Modern Ireland, 1600–1972 (London, 1988). 8. Roy Foster, ‘We are all Revisionists Now’, in Irish Review (Cork, 1986), pp. 1–6. 9. Professor Seamus Metress, The Irish People, 10 January 1996. Similar arguments have also been expressed by Professor Brendan Bradshaw of Cambridge Univer- sity, a consistent – but isolated – opponent of revisionist interpretation. See, for example, Irish Historical Studies, xxvi: 104 (November 1989), pp. 329–51. 10. Christine Kinealy, ‘Beyond Revisionism’, in History Ireland: Reassessing the Irish Famine (Winter 1995). 11. For more on this episode, see Cormac Ó Gráda, ‘Making History in Ireland in the 1940s and 1950s: The Saga of the Great Famine’, in The Irish Review (1992), pp. -

Race', Nation and Belonging in Ireland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Arrow@dit Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies Est 1998. Published by Social Care Ireland Volume 11 Issue 1 2011 'Race', Nation and Belonging in Ireland Jonathan Mitchell University College Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijass Recommended Citation Mitchell, Jonathan (2011) "'Race', Nation and Belonging in Ireland," Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 1. doi:10.21427/D7VD9H Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijass/vol11/iss1/1 4 Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies ‘Race’, Nation and Belonging in Ireland Jonathan Mitchell [email protected] This paper was the award winning entry in the Social Studies category of the 2011 Undergraduate Awards of Ireland and Northern Ireland 1 which the author completed as part of his studies at the School of Sociology, Social Policy and Social Work, Queen’s University Belfast. © Copyright Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies ISSN 1393-7022 Vol. 11(1), 2011, 4-13 Abstract Despite consistent efforts to counteract those attitudes and practices that give rise to it, most putatively modern Western nations continue to experience the concrete effects of racial discrimination. This essay argues that nationality is all too easily conflated with ‘race’ or ethnicity, such that a seeming essence or givenness is manifested amongst all those within a particular geographic boundary. It is suggested that on the contrary, there is nothing natural about nationality as commonly understood; this being so, it must be continually shored up and reconstituted through social, linguistic and material practices. -

Organ Donor Awareness Week 2017

Organ Donor Awareness Week 2017 www.ika.ie/organ-donor-awareness-week-2016 MEDIA COVERAGE 2016 Saturday 9th of April: Grainne spreads organ donation message on tv - Kerryman Maurice given gift of life with two transplants – Enniscorty Guardian Everyone has the opportunity to give the gift of hope and life to a latter day hero – Irish Independent Vivienne is supporting organ donor week – Fingal Independent “She saved 3 people – there is peace in that” - The Journal Wexford’s Sabia hasnt looked back since life-changing transplant – Wexford People Friday 8th of April: Organ Donation a lifeline for lexi - The Irish Examiner My kidney transplant gave me the gift of life – and my future wife – Irish independent 6 Year old needs a new kidney and liver to survive – The Journal Thursday 7th of April: Gratitude and Organ Donors – Irish Times Ex Roscommon star marries his pharmacy technician - Hogan Stand So hard that a family in grief must make donation decision to help our little girl - The Western People 1/5 Wednesday 6th of April: 6 year old waterford girl requires a liver and kidney transplant - Waterford Today This video aims to transform lives - Breaking News 2 Irishmen randomly met at a bog and ended up changing each others lives – Joe.ie Irish mans life saved by stranger he met at the bog – Irish Independent Leo Varadkar says family agreement and next of kin consent would still be needed - Irish Times Playing the waiting game – Dublin People Tuesday 5th of April: Organ Donor awareness week - Clare Courier Vivienne Traynor: Carry card and