Go on Go: the Analyzed Games of Go Seigen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The AGA Song Book up to Date

3rd Edition Songs, Poems, Stories and More! Edited by Bob Felice Published by The American Go Association P.O. Box 397, Old Chelsea Station New York, N.Y., 10113-0397 Copyright 1998, 2002, 2006 in the U.S.A. by the American Go Association, except where noted. Cover illustration by Jim Rodgers. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the copyright holder, except for brief quotations used as part of a critical review. Introductions Introduction to the 1st Edition When I attended my first Go Congress three years ago I was astounded by the sheer number of silly Go songs everyone knew. At the next Congress, I wondered if all these musical treasures had ever been printed. Some research revealed that the late Bob High had put together three collections of Go songs, but the last of these appeared in 1990. Very few people had these song books, and some, like me, weren’t even aware that they existed. While new songs had been printed in the American Go Journal, there was clearly a need for a new collection of Go songs. Last year I decided to do whatever I could to bring the AGA Song Book up to date. I wanted to collect as many of the old songs as I could find, as well as the new songs that had been written since Bob High’s last song book. You are holding in your hands the book I was looking for two years ago. -

Lesson Plans for Go in Schools

Go Lesson Plans 1 Lesson Plans for Go in Schools By Gordon E. Castanza, Ed. D. October 19, 2011 Published By Rittenberg Consulting Group 7806 108th St. NW Gig Harbor, WA 98332 253-853-4831 ©Gordon E. Castanza, Ed. D. 10/19/11 DRAFT Go Lesson Plans 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose/Rationale ........................................................................................................................... 5 Lesson Plan One ............................................................................................................................. 7 Basic Ideas .................................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 11 The Puzzle ................................................................................................................................. 13 Surround to Capture .................................................................................................................. 14 First Capture Go ........................................................................................................................ 16 Lesson Plan Two ........................................................................................................................... 19 Units & -

T Sin G Hu a U N Iv E Rs It Y

NEWSLETTER July 2013 No. 3 Vol. 7 National | Tsing Hua | University TY I RS E ONAL I IV NAT TSING HUA N CONTENTS U 1 NTHU Continues Improving in QS Ranking 2 Go Masters Gathered in Yi Yuan 3 The Grand Opening of Macronix Learning Resource Center 4 Dr. Po-Yu Chen Published a Review Article in Science 5 Exploring the Future: TEDxNTHU 6 Three Distinguished Alumni Honored During the Anniversary Celebration 7 NTHU Joins YouTube EDU 8 NSC STEP Consortium and NTHU-TSMC Center for Manufacturing Excellence 9 NTHU Celebrated Poet Chou-Yu Cheng's 80th Birthday with Music and Poetry 10 The First Taiwanese Chemist Featured in the Author Profile 11 Innovative and Creative Ideas to Improve the Quality of University Service NTHU CONTINUES IMPROVING IN QS RANKING uacquarelli Symonds seven research papers authored by from the collective efforts of all recently announced its Taiwanese scholars and appeared faculty members and students. ranking of various fields in Science and Nature last year "We have improved our curricula, Qof study among top universities are the works of NTHU faculty and research capability as well as the worldwide. In this most recent graduate students. Moreover, since administrative services. We will ranking, NTHU has 11 fields of the beginning of 2013, NTHU has continue doing our very best to make study ranked in the top 200. Among four more additional research papers NTHU a comprehensive institution the 11 fields, chemical engineering published or accepted by Science . of higher learning where students and mechanical engineering have This means that NTHU has published will not only be well trained as moved up to the spot of 49th. -

Universi in Bianco E Nero

El go1 Hoy, nueve de setiembre de 1978, tuve en la palma de la mano un pequeño disco de los trescientos sesenta y uno que se requieren para el juego astrológico del go, ese otro ajedrez del Oriente. Es más antiguo que la más antigua escritura y el tablero es un mapa del universo. Sus variaciones negras y blancas agotarán el tiempo. En él pueden perderse los hombres como en el amor y en el día. Hoy nueve de setiembre de 1978, yo, que soy ignorante de tantas cosas, sé que ignoro una más, y agradezco a mis númenes esta revelación de un laberinto que nunca será mío. Jorge Luis Borges 1 Traduzione in appendice. I Il go: universi in bianco e nero Indice Introduzione ………………………………………………………………… 1 1. Breve introduzione al go 1.1 Il gioco ..………………………………………………………….. 5 1.2 I materiali ..……………………………………………………….. 5 2. Uno sguardo dall’interno: il Giappone e il tramonto delle tradizioni 2.1 Il maestro di go di Kawabata Yasunari ……………….………..…. 7 2.2 La lotta contro la modernità .…………………………………...…. 9 2.3 La figura del maestro …………………………………………….. 13 3. Tra Cina e Giappone: lo spirito guerriero e la libertà 3.1 La giocatrice di go di Shan Sa ………………………….……….. 17 3.2 La fedeltà al proprio signore e la cessazione del desiderio .......…. 20 3.3 Lo specchio dell’anima ...………………………….….………….. 24 4. L’Occidente e la ricerca della spiritualità 4.1 Shibumi di Trevanian …………………….…………….……….... 28 4.2 Oriente e Occidente: poesia e autocontrollo ...………………….... 30 4.3 Shibumi: la raffinatezza sotto apparenze comuni ...…………….... 35 5. Il go e gli altri media …………………………………………………….. 38 Conclusioni ………………………………………………………….……... -

Obama Vs. Putin „Gehe Nicht Auf Die Jagd, Wenn Dein Haus Brennt.“

Heft 3/2016 91. Jahrgang Obama vs. Putin „Gehe nicht auf die Jagd, wenn dein Haus brennt.“ 1 DGoZ 3/2016 Inhalt Vorwort Der Hebsacker Verlag sowie seine Inhaber, Steffi Obama vs. Putin .................................Titel Hebsacker und ich, sind umgezogen, raus aus Vorwort, Inhalt, Fangen und Retten, Hamburg, aufs Land, in ein großes Haus, das jetzt Nachrichten .................................2–5 die privaten und die Geschäftsräume vereint. Ein Turnierberichte ..........................6–14 solches Unterfangen kann naturgemäß auch an der Leserbrief ........................................... 14 DGoZ nicht ganz spurlos vorüber gehen, so dass Kawabatas „Meijin“ ..................... 15–16 diese Ausgabe leider ca. vier bis fünf Wochen zu spät Rezension: Jump Up 6–10 ........... 16–18 erscheint, aber dafür hoffentlich trotzdem noch das Sommerloch bei vielen Go-Fans zu stopfen hilft. Vertretungsstunden mit Go ................ 19 Ein großer Schwerpunkt liegt bei dieser dritten Anfängerprobleme ....................... 20–21 Ausgabe des Jahres traditionell auf dem Kidocup, der Der etwas andere Zug (14) ........... 22–26 wohl auch in diesem Jahr wieder das größte Wochen- Ausschreibung DDGM ...................... 23 endturnier in Europa sein wird. Zwei Partien aus der Dragon Fly ........................................ 27 Top-Gruppe hat Yoon Young Sun 8p gewohnt sou- Durchbruch zum 18. Kyu (3) ...... 28–29 verän und instruktiv kommentiert. Viel Spaß damit! Pokale ..........................................30–31 Tobias Berben Yoon Young Sun kommentiert -

GO WINDS - Stronger Go Engine

NEW NEW MANYFACES OF GO YUTOPIAN BOOKS GO WINDS - Stronger Go Engine. It's several stones stronger than version 10 and won the world A Scientific computer go championship in 1998 and took Volume 7 Number 3 Fall 2003 $3.00 second in 2001. Introduction to Go - New and improved go problems. Over 2000 go problems for all levels of play. The program It is often difficult for beginners to learn go, selects problems for you according to how well because most teachers emphasize on teaching you have solved previous problems. Problems the development of local situations and fail to are shown in random orientations so it's like convey the more profound theory and concepts having 16,000 problems. of the global game. This book tries to break - Built in IGS client so you can play on the through the traditional system of teaching go, Internet using a familiar interface. which emphasizes experience alone. The - Realistic sounds language and illustrations used in this book can - Improved Printing. Print game series be easily comprehended by kids, so that diagrams. everyone can understand these profound global Other new features include: concepts. It is our goal that through this book - Better game navigation and editing: Ctrl-click everyone can learn to understand and enjoy the on a point to go to a play. Delete this play and game of go! 288 Pages Size: 7 1/2 by 10 1/4 all plays to the end of the game. Promote a play Price: $22.00 + $2.50 s/h to be the main line rather than a variation. -

GO WINDS Play Over 1000 Professional Games to Reach Recent Sets Have Focused on "How the Pros 1-Dan, It Is Said

NEW FROM YUTOPIAN ENTERPRISES GO GAMES ON DISK (GOGoD) SOFTWARE GO WINDS Play over 1000 professional games to reach Recent sets have focused on "How the pros 1-dan, it is said. How about 6-dan? Games of play the ...". So far there are sets covering the Go on Disk now offers over 6000 professional "Chinese Fuseki" Volume I (a second volume Volume 2 Number 4 Winter 1999 $3.00 games on disk, games that span the gamut of is in preparation), and "Nirensei", Volumes I go history - featuring players that helped and II. A "Sanrensei" volume is also in define the history. preparation. All these disks typically contain All game collections come with DOS or 300 games. Windows 95 viewing software, and most The latest addition to this series is a collections include the celebrated Go Scorer in "specialty" item - so special GoGoD invented which you can guess the pros' moves as you a new term for it. It is the "Sideways Chinese" play (with hints if necessary) and check your fuseki, which incorporates the Mini-Chinese score. pattern. Very rarely seen in western The star of the collection may well be "Go publications yet played by most of the top Seigen" - the lifetime games (over 800) of pros, this opening is illustrated by over 130 perhaps the century's greatest player, with games from Japan, China and Korea. Over more than 10% commented. "Kitani" 1000 half have brief comments. The next specialty makes an ideal matching set - most of the item in preparation is a set of games featuring lifetime games of his legendary rival, Kitani unusual fusekis - this will include rare New Minoru. -

Curriculum Guide for Go in Schools

Curriculum Guide 1 Curriculum Guide for Go In Schools by Gordon E. Castanza, Ed. D. October 19, 2011 Published By: Rittenberg Consulting Group 7806 108th St. NW Gig Harbor, WA 98332 253-853-4831 © 2005 by Gordon E. Castanza, Ed. D. Curriculum Guide 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose and Rationale..................................................................................................................... 5 About this curriculum guide ................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Overview ................................................................................................................................. 9 Building Go Instructor Capacity ........................................................................................... 10 Developing Relationships and Communicating with the Community ................................. 10 Using Resources Effectively ................................................................................................. 11 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 11 Major Trends and Issues .......................................................................................................... -

Lehrbücher Deutsche Literatur Englische Literatur

Lehrbücher Deutsche Literatur Titel Bände Autor / Übersetzer Jahr Verlag Ort ISBN Lehrstunden in den Grundlagen des Go Kageyama Toshiro 7-Dan 2009 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563057 Problem Go für Fortgeschrittene Nobuaki Maeda 9-Dan 1974 Karl Lehwald Hamburg '--- Go Probleme für Genießer Erwin Gerstorfer 2012 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563194 Strategien und Taktiken des Go-Spiels Richard Bozulich 2009 Hebsacker Verlag Hamburg 9783937499055 SANREN-SEI Die Power-Eröffnung Takagawa Shukaku 9-Dan 2010 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563132 Deutsche Meisterschaft 2009 Gunnar Dickfeld 2010 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563101 Deutsche Meisterschaft 2007 Gunnar Dickfeld 2008 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563033 Deutsche Go-Meisterschaft 2004 Tobias Berben 2005 Hebsacker Verlag Hamburg 3937499016 Chinesische Meisterpartien Guo Juan 2008 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563040 GO-der richtige Zeitpunkt Jürgen Mattern 1991 Carola Wild Kassel 3928435019 GO Das älteste Brettspiel der Welt Siegmar Steffens 2004 Rittel Verlag 3936443033 Die Schatztruhe Nakayama Noriyuki 6-Dan 2008 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563026 Die Kunst des Angriffs Kato Masao 9-Dan 2009 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563064 Lehrbücher des Go Band 1 Elementare Techniken Thomas Hillebrand 2013 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563415 Band 2 Leben und Tod Gunnar Dickfeld 2013 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563422 Band 4 Strategie Richard Bozulich 2013 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563446 Lexikon der Joseki: Band 2 Takao Shinji 9-Dan 2012 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. 9783940563163 Band 3 Takao Shinji 9-Dan 2012 Brett und Stein Frankfurt a.M. -

Sydney Go Journal

Author – David Mitchell on behalf of The Sydney Go Club Sydney Go Journal Issue Date - November 2006 31st Meijin to be settled in November Takao Shinji won the 4th game to take the Meijin title by half a point. At 364 moves this is the longest finals game in Japanaese Go history. Facing kadoban (sudden death) Cho fought back in the 5th Game to win by resignation. The title and US$200,000 will now be settled in November. A brief background of the players…. Takao Shinji was born on 26th October 1976 in Chiba City, Chiba Pref. Japan. He has risen quickly through the ranks going from 1p in 1991 to 9p in 2005 (an automatic promotion for winning the Honinbo title) under the guidance of Fujisawa Shuko sensei (9p). In July 2003 he reached 500 wins having played only 660 games – a 75.8% win rate. In January 2006 he became the youngest ever to reach 600 wins and only the 40th player ever to achieve the goal. Cho U was born on the 20th January 1980 in Taipei, Taiwan. He moved to Japan in 1990 as a pupil of Rin Kaiho. He was Insei in 1990, progressing to 9p in 2003; in doing so he set a record for the fastest promotion to 9-dan - 9 years three months. During his career he has set many records, at 21 he was the youngest major title challenger ever for Honinbo in 2001; he held the Japanese record for most wins in a year (70) in 2002, and the longest winning streak in the Oteai: 37 games. -

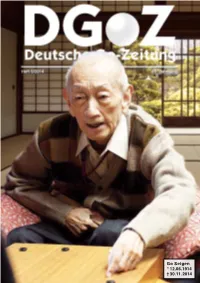

Go Seigen * 12.06.1914 † 30.11.2014

Go Seigen * 12.06.1914 1 † 30.11.2014DGoZ 6/2014 Inhalt Vorwort Go Seigen, *12.06.1914 †30.11.2014 .... 1 Wie heißt es so schön in Bertolt Brechts „Ballade von der Unzulänglichkeit menschlichen Planens“? Vorwort, Inhalt, Fangen und Retten ...... 2 Ja, mach nur einen Plan! Nachrichten ................................... 2–4 Sei nur ein großes Licht! Turnierberichte .............................. 5–8 Und mach dann noch ’nen zweiten Plan 10 Jahre Go-Bundesliga ...................... 9 Gehn tun sie beide nicht. Go Seigen und die Liebe für Go . 10–15 Den „üblichen“ Monat sollte die letzte Ausgabe Pokale ......................................... 16–17 verspätet erscheinen, leider sind doch sechs Wochen daraus geworden, weil die Druckerei die Druckvor- Paar-Go in Japan (1) ................... 18–21 lage mal eben einfach 10 Tage hat rumliegen lassen, Wann stirbt die Hoffnung? ......... 22–26 anstatt zu drucken. Immerhin musste sie danach Kinderseite .................................. 27–29 sofortigen Druck zusagen, was bei der Ausgabe zu Yoon Young Sun kommentiert (22) .. 30–33 angenehm dickerem Papier ohne Aufpreis geführt Japan oder die Eroberung einer fernen hat. Bleibt mir nur, für diese Ausgabe eine schnel- Galaxie (Teil 2) ............................ 34–41 lere Bearbeitung zu erhoffen und allen Lesern ein erfolgreiches und gesundes Jahr 2015 zu wünschen! Der etwas andere Zug (6) ............ 42–47 Tobias Berben Impressum ........................................ 47 Fernostnachrichten ..................... 48–49 Anzeige: Omikron Data Quality GmbH .50 Go-Probleme ............................. 51–54 Deutschlandpokal 2014 Ausschreibung: DPGM 2015 ............ 54 Der Deutschlandpokal 2014 hat mit dem Berliner Spielabendliste ............................ 55–64 Kranich seinen Abschluss gefunden und wir gratu- Mitgliedsantrag ................................ 65 lieren den Preisträgern DGoB-Organe ................................. 66 Gruppe A Anzeige: Hebsacker Verlag ............... 67 1. Dan Groza Turnierkalender ................... -

Go Seigen-Hashimoto

Chapter 7 Go Seigen-Hashimoto Hashimoto Utaro is probably best known of two things: his leadership in the Kansai Ki’in and his long Go career. According to the Go Player’s Almanac (Ishi Press, 1992), he probably holds the all-time longevity record for a professional (and he’s extending this record; he was born in February 1907). Being a 3-time Honinbo title winner and the loser in the 1st Kisei title match (to Fujisawa Shuko), Hashimoto has also composed a tsume-go problem a day for several decades! Some of his games with Go Seigen in his early years were associated with some interesting stories. In 1933, Kitani Minoru and Go Seigen spent a summer together in Nagano (Mrs. Kitani’s hometwon). When the autumn arrived, their return to Tokyo marked the be- ginning of the New Fuseki Era. (Of course, both players had had thoughts on new openings and had tried some new moves before the summer; a revolution doesn’t occur in one day or two.) Just at this time, Yomiuri Newspaper sponsered a Japanese Go Championship to celebrate the publication of the No. 20,000 of the newspaper. It was a knockout tour- nament in which sixteen 5-dan or above players (i.e. perhaps all the top players at the time) participated. The winner would earn the bonus to play a game against Meijin Honinbo Shusai (9-dan). The finalists were Go Seigen and Hasahimoto Utaro. As mentioned above, Kitani and Wu had just brought New Fuseki to the Go world, and this new style of playing immediately became popular.