Of Music and Media: a Producer Study of Promotional Encoding on Social Media Through the Lenses of Paratext and Medium Theory Connor D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Indie Institutions in the London, Ontario Independent-Music Scene

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-13-2013 12:00 AM Treasuries of Subcultural Capital: Three Indie Institutions in the London, Ontario Independent-Music Scene Samuel C. Allen The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Samuel C. Allen 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Community-Based Research Commons Recommended Citation Allen, Samuel C., "Treasuries of Subcultural Capital: Three Indie Institutions in the London, Ontario Independent-Music Scene" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1460. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1460 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TREASURIES OF SUBCULTURAL CAPITAL: THREE INDIE INSTITUTIONS IN THE LONDON, ONTARIO INDEPENDENT-MUSIC SCENE (Thesis format: Monograph) by Samuel Charles Allen Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Popular Music and Culture The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Samuel Charles Allen 2013 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the role institutions play within the London, Ontario independent-music scene. Institutions are where indie-music scenes happen (Kruse 2003). -

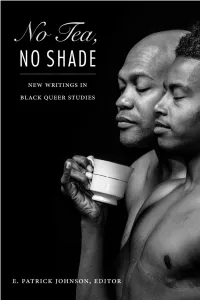

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Weirdo Canyon Dispatch 2018

Review: Roadburn Thursday 19th April 2017 By Sander van den Driesche It’s that time of the year again, the After Yellow Eyes it’s straight to the much anticipated annual pilgrimage to Main Stage to see Dark Buddha Rising Tilburg to join with many hundreds of perform with Oranssi Pazuzu as the travellers for Walter’s party at Waste of Space Orchestra, which is Roadburn. As I get off the train the another highly anticipated show, and in heat kicks me right in the face, what a this case one that won’t be played massive difference to the dull and rainy anywhere else (as far as I know). What morning I left behind in Scotland. This happened on that big stage was is glorious weather for a Roadburn phenomenal, we witnessed a near hour Festival! Bring it on! of glorious drone-infused psychedelic proggy doom. In fact, it felt a bit too early for me personally in the timing of the festival to experience such an extraordinarily mind-blowing set, but it was a remarkable collaboration and performance. I can’t wait for the Live at Roadburn release to come out (someone make it happen please!). Yellow Eyes by Niels Vinck After getting my bearings with the new venues, I enter Het Patronaat for the first of my highly anticipated performances of the festival, Yellow Eyes. But after three blistering minutes of ferocious black metal the PA system seems to disagree and we have our first “Zeal & Ardor moment” of 2018. It’s Waste of Space Orchestra by Niels Vinck not even remotely funny to see the On the same Main Stage, Earthless Roadburn crew frantically trying to played the first of their sets as figure out what went wrong, but luckily Roadburn’s artist in residence. -

1 Senior Freshman 2013-14 Department of Sociology (12 Week

Senior Freshman 2013‐14 Department of Sociology GENDER, CULTURE AND SOCIETY (2ND SEMESTER) SUBCULTURES AND GENDER (12 week module, January – April 2014) Dr Maja Halilovic‐Pastuovic The aim of this second half of the year is to present some more contemporary perspectives on gender and society. It does so through looking at the importance of the concept of ‘subculture’ in 20th century sociology and the difficulties encountered in combining this with a gender analysis. Were the early studies simply ‘gender‐ blind’? or should they be read rather as studies of rampant masculinity? Is ‘femininity’ itself a sub‐culture? If so, then how can half of humanity form a ‘sub’‐ culture? These are the kinds of questions we have to address when we follow these two strands of sociology – subcultures and gender – and see where they intersect. Much of the initial work on subcultures showed a fascination with ‘resistant’ masculine identities (from jazz musicians and marijuana users, to mods and rockers, punks and rastas), and we will study some of this work and its importance in debates about conformity and ‘deviance’ in the USA, and in social class and class conflict in the UK. It was a while before feminist researchers were able to point up this masculine bias, and bring women into a more complicated picture that shows both the reproduction of family values within female urban gangs in the USA, and the double rebellion involved in being a punk teenager with a Mohican and torn t‐shirt in a girls’ school. However, we shall also be doing some re‐reading of the earlier studies to see what they tell us about masculinity, even if this is not what their authors initially intended. -

New Releases & Discoveries 2017 (Click for PDF)

January 1, 2016 56 seasons by flyingdeadman (France) https://flyingdeadman.bandcamp.com/album/56-seasons-2 released January 5, 2017 When You're Young You're Invincible by Dayluta Means Kindness (El Paso, Texas) https://dayluta.bandcamp.com/album/when-youre-young-youre-invincible released January 6, 2017 Icarus by Sound Architects (Quezon City, Philippines) https://soundarchitects.bandcamp.com/track/icarus released January 6, 2017 0 by PHONOGRAPHIA (attenuation circuit - Augsburg, Germany) https://emerge.bandcamp.com/album/0-2 released January 1, 2017 Chill Kingdom by The American Dollar (New York) https://theamericandollar.bandcamp.com/track/chill-kingdom released January 1, 2017 Anticipation of an Uncertain Future by Various Artists (Preserved Sound - Hebden Bridge, UK) https://preservedsound.bandcamp.com/album/anticipation-of-an-uncertain-future released January 1, 2017 Swimming Through Dreams by Black Needle Noise with Mimi Page (Oslo, Norway) https://blackneedlenoise.bandcamp.com/track/swimming-through-dreams released January 1, 2017 The New Empire by cétieu (Warsaw, Poland) https://cetieu.bandcamp.com/album/the-new-empire released January 1, 2017 Live at the Smilin' Buddha Cabaret by Seven Nines & Tens (Vancouver) https://sevenninesandtens.bandcamp.com/album/live-at-the-smilin-buddha-cabaret released January 1, 2017 EUPANA @ VIVID POST-ROCK FESTIVAL-2016 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcX3VKgaVsE Published on 1 Jan 2017 Clones by Vacant Stations (UK) https://vacantstations.bandcamp.com/album/clones released January 1, 2017 Presence, -

After-School Mentorship Program and Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Middle-School Students Atia D

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2018 After-School Mentorship Program and Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Middle-School Students Atia D. Mark Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Education This is to certify that the doctoral study by Atia D. Mark has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Steve Wells, Committee Chairperson, Education Faculty Dr. Gloria Jacobs, Committee Member, Education Faculty Dr. Michael Brunn, University Reviewer, Education Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2018 Abstract After-School Mentorship Program and Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Middle-School Students by Atia D. Mark MA, Concordia University, 2012 BS, University of the West Indies, 2009 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education Walden University August 2018 Abstract Middle-school students in Nova Scotia are perceived to have low self-efficacy for achieving learning outcomes. Strong self-efficacy beliefs developed through effective curricula have been linked to improved academic performance. However, there is a need for the formal evaluation of effective curricula that aim to improve self-efficacy. -

Enthusiastic Cactus Promotes RHA at Stockton Get Involved Fair Artist

} “Remember, no one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” -Eleanor Roosevelt President Donald Trump’s First State of Union The Address Argo (gettyimages) The Independent Student Newspaper of Stockton University February 5, 2018 VOLUME 88 ISSUE 15 PAGE 7 Stockton in Manahawkin Opens Larger Site, Expands In This Issue Health Science Programs Diane D’Amico additional general education courses for the convenience FOR THE ARGO of students living in Ocean County. “I love it, said student Ann Smith, 21, of Ma- nahawkin, who along with classmates in the Accelerated BSN, or TRANSCEL program, used the site for the first time on Jan. 18. The Accelerated BSN students will spend one full (twitter) day a week in class at the site in addition to their clinical assignments and other classes. Former Stockton Employee is Art work from the Noyes Museum collection, in- Now Professional Wrester cluding some by Fred Noyes, is exhibited throughout the site, adding color and interest. PAGE 5 “It is much more spacious and very beautiful,” said student Christian Dy of Mullica Hill. The new site includes a lobby/lounge area with seating where students can eat lunch. There is a faculty lounge and small student hospitality area with snacks and (Photo courtesy of Stockton University) coffee. “They are here all day, and we want to them feel Students arriving for the spring semester at Stock- welcomed and comfortable,” said Michele Collins-Davies, ton University at Manahawkin discovered it had grown to the site manager. (liveforlivemusic) more than three times its size. “They did a really good job,” said student Lindsay The expansion into the adjacent 7,915 square-foot Carignan of Somers Point, who said her drive is a bit lon- LCD Soundsystem’s First building at 712 E. -

Art and Luxury: How the Art Market Became a Luxury Goods Business – Revisited

Art and luxury: how the art market became a luxury goods business – revisited London law firm for creative industries Crefovi publishes its latest proprietary research in the art and luxury issue of INFO Magazine, in relation to the interactions between the art and luxury sectors. I came across an interesting piece, on Phaidon’s website, recently, entitled ‟How the art market became a luxury goods business”. This blog post describes the reactions to, and contains an interview about, artist Andrea Fraser’s essay entitled ‟L’1 pour cent c’est moi”, freely available to download from the Whitney Museum’s website as part of its 2012 Biennial. In her essay, the California-based artist and professor at UCLA stresses her concerns that today, art is not only an asset class for the financial elite, but has also become a financial instrument. She also states that, the greater the discrepancy between the rich and the poor, the higher prices in the art market rise. According to Ms Fraser, while there is a direct link – quantified in recent economic research [1] – between the art market boom and economic inequality that has reached levels not seen since the ‘20s in the US and the ‘40s in Britain, it is not just the art market that has expanded from this unprecedented concentration of wealth but museums, art prizes, residences, art schools, art magazines have multiplied in the past decade. She expresses her uneasiness at working in the art field, which has benefited from, and, as an artist, having personally benefited so directed from, the anti-union, anti-tax, anti-regulation, anti-public sector politics that have made this concentration of wealth possible. -

Sarah Thornton and the State of Art

BY DEA VANAGAN Since exploding onto the scene in 2008 with her now-cult book Seven Days in the Art World, Sarah Thornton has charted a meteoric rise and won international influence. Her bold and inquisitive analysis of the art world and its wider impact has engaged and inspired a new audience to enter the debate. She tours around the globe giving lectures and interviewing some of the most prominent living artists in the world, and her clever and thorough style has helped position her as one of today’s key authorities on the con- temporary art world and art market. Her latest book, 33 Artists in 3 Acts, hits the shelves this November and dares to ask (and offer answers to) the difficult question: “What is an artist?” I caught up with the hierarchy-transcending writer, currently based in London, ahead of the release of her latest publication. Thornton is a self-professed “research nut” with a commitment to accuracy, and everything she says is considered and purposeful. There is never a dead silence, only strategic pauses before sharing her well-defined views. She manages to give off a strong sense of conviction without ever sounding aggressive or sanctimonious. Putting inter- viewees at ease is a great skill of hers that is apparent almost immediately upon meeting her. She is energetic, explorative and genuinely curious. Thornton credits her success in art history to having “a photographic memory as a child” and being “very visually dominant,” so it is fitting that when arranging to meet, she decided that the perfect setting for our interview would be Tate Modern. -

Download This Judgment

Thornton v Telegraph Media Approved Judgment Neutral Citation Number: [2011] EWHC 1884 (QB) Case No: HQ09X02550 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 26/07/2011 Before : THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : SARAH THORNTON Claimant - and - TELEGRAPH MEDIA GROUP LTD Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Ronald Thwaites QC & Justin Rushbrooke (instructed by Taylor Hampton) for the Claimant David Price QC & Catrin Evans (instructed by David Price Solicitors and Advocates) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 4, 5, 6, 8 July - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment Mr Justice Tugendhat : 1. Sarah Thornton makes two claims in this action: one in libel and one in malicious falsehood. Both claims arise out of a review (“the Review”) written by Lynn Barber of Dr Thornton’s book “Seven Days in the Art World” (“the Book”). The Review was published in the print edition of the Daily Telegraph dated 1 November 2008, and thereafter in the online edition until taken down at the end of March 2009. The Defendant is the publisher (“the Telegraph”). 2. The pre-action protocol letter written by solicitors for Dr Thornton is dated 23 March 2009. The first meaning complained of, as subsequently set out in the Particulars of Claim, was that Dr Thornton had dishonestly claimed to have carried out an hour-long interview with Ms Barber as part of her research for the Book, when the true position was she had not interviewed Ms Barber at all, and had in fact been refused an interview. Thornton v Telegraph Media Approved Judgment 3. The second complaint, that of malicious falsehood, was that in the Review Ms Barber had stated that Dr Thornton gave copy approval to the individuals mentioned in the book whom she had interviewed, that is to say the right to see the proposed text in advance of publication, and to alter it, or to veto its publication. -

Kathryn Brown Private Influence, Public Goods, and the Future of Art History

ISSN: 2511–7602 Journal for Art Market Studies 1 (2019) Kathryn Brown Private Influence, Public Goods, and the Future of Art History ABSTRACT financial forces that shape them. From the per- spective of art history, however, this article sets The aim of this article is to consider potential out to explore concerns that the social meaning conflicts that arise when private wealth shapes of art and its histories (past and future) are in- the formation of cultural networks and deci- creasingly determined by a restricted group of sion-making. Drawing on examples from con- agents whose institutions often lack transpar- temporary exhibition and museum practices, ency and public accountability. The extension the author discusses the impact of private art of influence from the realm of private taste to collecting on the mission of public institutions that of public institution is a hallmark of the and considers examples of the wider extension contemporary artworld and its philanthropic of collectors’ influence in the art world. If one structures, including the founding of private of the roles of the public museum is to preserve museums. Taken together, these developments heritage for the interest and education of di- risk the creation of an art history from above, verse audiences throughout time, it is impor- where the financial power of a circumscribed tant to question the collective and individual demographic translates into the promotion of choices that underpin the creation of such specific intellectual, social, and aesthetic values cultural narratives as well as the social and for uncertain periods of time. From the exercise of influence on museum boards, to loans of privately owned artworks, the selection of national representatives at international exhibitions, or the founding of single donor museums, the power of private collectors has expanded exponentially over the past two decades from the sphere of personal taste into the realm of public exhibi- tion practices. -

ED382869.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 382 869 CE 069 050 TITLE Occupational Literacy. A Training Profile Development Project for Ontario Basic Skills/Formation de base de l'Ontario. INSTITUTION Ontario Ministry of Skills Development, Toronto. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 361p. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; Adult Literacy; *Basic Skills; *Behavioral Objectives; *Communication Skills; Computer Literacy; Employer Attitudes; Foreign Countries; French; Job Skills; *Literacy Education; *Numeracy; Profiles; Science Process Skills; Vocational Adjustment IDENTIFIERS Ontario; *Workplace Literacy ABSTRACT This document resulted from a project undertaken to develop a set of program-specific and occupationally relevant performance (learning) obje :tives for the Ontario Basic Skills/Formation de Base de 1'Ontario (OBS/FBO) program. It describes project activities, including a literature review in three related areas: understanding what literacy means, occupational literacy research findings, and basic skills for the workplace. Two project stages are discussed. The first is a survey in English and French of 325 Ontario (Canada) employers in 9 industrial sectors. The survey identified the core basic skills required at three entry levels to employment. The second stage is the consolidation of the survey findings into preliminary performance objectives for each of the six subject areas in OBS/FBO: communications, numeracy, science, computer literacy, work adjustment, and technical hands-on. The terminal performance objectives are presented in the body of the report. Appendixes, amounting to over one-half of the report, include the following,: lists of employers surveyed; survey results; provincial, regional, and sectoral results; occupational sector job positions; onsite points of observation; OBS terminal and enabling objectives; and FBO terminal and enabling objectives.