Gorman Dissertation 2012.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leveson Inquiry Into the Cultures, Practices And

For Distribution to CPs THE LEVESON INQUIRY INTO THE CULTURES, PRACTICES AND ETHICS OE THE PRESS WITNESS STATEMENT OE JAMES HANNING I, JAMES HANNING of Independent Print Limited, 2 Derry Street, London, W8 SHF, WILL SAY; My name is James Hanning. I am deputy editor of the Independent on Sunday and, with Francis Elliott of The Times, co-author of a biography of David Cameron. In the course of co-writing and updating our book we spoke to a large number of people, but equally I am very conscious that I, at least, dipped into areas in which I can claim very little specialist knowledge, so I would emphasise that in several respects there are a great many people better placed to comment and much of what follows is impressionistic. I hope that what follows is germane to some of the relationships that Lord Justice Leveson has asked witnesses to discuss. I hesitate to try to draw a broader picture, but I hope that some conclusions about the disproportionate influence of a particular sector of the media can be drawn from my experience. My interest in the area under discussion in the Third Module stems from two topics. One is in David Cameron, on whose biography we began work in late 2005, soon after Cameron became Tory leader. The second is an interest in phone hacking at the News of the World. Tory relations with Murdoch Since early 2007, the Conservative leadership has been extremely keen to ingratiate itself with the Murdoch empire. It is striking how it had become axiomatic that the support of the Murdoch papers was essential for winning a general election. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE :: Media Contact: Dana Marks (617) 536-5049 [email protected]

:: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE :: Media Contact: Dana Marks (617) 536-5049 [email protected] Images (L to R) :: Back Yard Dreams (detail) by Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, The Great Orator by Enrique Flores – Galbis, BITS (Poolside 2) by Gabriel Martinez LA CUBANA Y EL CUBANO September 10 – October 7 The Copley Society of Art is proud to present La Cubana y el Cubano, an exhibition of Cuban art with works by Cuban and Cuban-American artists, curated by Camilø Álvårez. This exhibition runs from September 10th through October 6th, 2016, at the Co|So gallery, located at 158 Newbury Street, Boston, MA 02116. An opening reception on Saturday, September 10th from 5:30 – 7:30pm will have refreshments, light snacks, and festive music. La Cubana y el Cubano, curated by Camilø Álvårez, Director of Samsøñ, features work by the following artists: Augusto Bordelois, Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, Adrian Fernández, Magda Fernández, Enrique Flores- Gablis, Luis Gispert, Olivia Ives-Flores, Carlos Martiel and Gabriel Martinez. Please see abbreviated bios below for participating artists: Augusto Bordelois (b. 1969, Havana, Cuba) lives and works in Cleveland, OH. As a painter, he combines fairy tales and personal dreams, inserting them into dramatic situations, or day to day happenings, to explore subjects like the power of the feminine. He has presented solo exhibitions with River House Arts (Toledo, OH), Steve Martin Fine Art (New Orleans, LA), and Cleveland State University (Cleveland, OH). Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons (b. 1959, Matanzas, Cuba) currently lives and works in Boston, MA. Through installation, photography and cultural activism, she explores history, memory and their connection to the formation of identity. -

Sturm Und Drang : JONAS BURGERT at BLAIN SOUTHERN GALLERY DAFYDD JONES : JONAS BURGERT at JONAS BURGERT I BERLIN

FREE 16 HOT & COOL ART : JONAS BURGERT AT BLAIN SOUTHERN GALLERY : JONAS BURGERT AT Sturm und Drang DAFYDD JONES JONAS BURGERT I BERLIN STATE 11 www.state-media.com 1 THE ARCHERS OF LIGHT 8 JAN - 12 FEB 2015 ALBERTO BIASI | WALDEMAR CORDEIRO | CARLOS CRUZ-DÍEZ | ALMIR MAVIGNIER FRANÇOIS MORELLET | TURI SIMETI | LUIS TOMASELLO | NANDA VIGO Luis Tomasello (b. 1915 La Plata, Argentina - d. 2014 Paris, France) Atmosphère chromoplastique N.1016, 2012, Acrylic on wood, 50 x 50 x 7 cm, 19 5/8 x 19 5/8 x 2 3/4 inches THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING: 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ CAREL VISSER, 18 FEB - 10 APR 2015 TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com JAN_AD(STATE).indd 1 03/12/2014 10:44 WiderbergAd.State3.awk.indd 1 09/12/2014 13:19 rosenfeld porcini 6th febraury - 21st march 2015 Ali BAnisAdr 11 February – 21 March 2015 4 Hanover Square London, W1S 1BP Monday – Friday: 10.00 – 18.00 Saturday: 10.00 – 17.0 0 www.blainsouthern.com +44 (0)207 493 4492 >> DIARY NOTES COVER IMAGE ALL THE FUN OF THE FAIR IT IS A FACT that the creeping stereotyped by the Wall Street hedge-fund supremo or Dafydd Jones dominance of the art fair in media tycoon, is time-poor and no scholar of art history Jonas Burgert, 2014 the business of trading art and outside of auction records. The art fair is essentially a Photographed at Blain|Southern artists is becoming a hot issue. -

Oral History Interview with Patricia Faure, 2004 Nov. 17-24

Oral history interview with Patricia Faure, 2004 Nov. 17-24 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Patricia Faure on November 17, 22, 24, 2004. The interview took place in Beverly Hills, California, and was conducted by Susan Ehrlich for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Patricia Faure and Susan Ehrlich have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MS. SUSAN EHRLICH: This is Susan Ehrlich interviewing Patricia Faure in her home in Beverly Hills, California, on November 17, 2004, for the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution. This is Disc Number One, Side One. Well, let’s begin with your childhood, where were you born, when were you born, and tell me about your early life and experience? MS. PATRICIA FAURE: I was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on April 8, 1928. I grew up there as well, went to school there, until I was 15, when we moved to Los Angeles, because after I was born, immediately after I was born, I got pneumonia. And I had pneumonia at least twice before I was six months old, and at one time the hospital called my parents and said to come and see me, for the last time. -

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT New York, NY 10014

82 Gansevoort Street JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT New York, NY 10014 p (212) 966-6675 allouchegallery.com Born 1960, Brooklyn, NY Died 1988, Manhattan, NY SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Boom for Real, Shirn exhibition hall, Frankfurt, Germany 2015 Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY 2015 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s the Time, Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario, Canada. Travelled to: Guggenheim Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain 2013 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Paintings and Drawings, Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, Switzerland 2012 Warhol and Basquiat, Arken Museum of Modern Art, Ishøj, Denmark 2010 Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Fondation Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland. Traveled to: City Museum of Modern Art, Paris, France 2006 The Jean-Michel Basquiat show, Fondazione La Triennale di Milano, Milan, Italy 2006 Jean-Michel Basquiat 1981: The Studio of the Street, Deitch Projects, New York, NY 2005 Basquiat, Curated by Fred Hoffman, Kellie Jones, Marc Mayer, and Franklin Sirmans Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY Traveled to: Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX 2002 Andy Warhol & Jean-Michel Basquiat: Collaboration Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA 1998 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Drawings & Paintings 1980-1988, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA 1997 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Oeuvres Sur Papier, Fondation Dina-Vierny-Musée Maillol, Paris, France 1996 Jean-Michel Basquiat, Serpentine Gallery, London, England; Palacio Episcopal de Mágala, Málaga, Spain 1994 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Works in Black and White, -

Three Indie Institutions in the London, Ontario Independent-Music Scene

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-13-2013 12:00 AM Treasuries of Subcultural Capital: Three Indie Institutions in the London, Ontario Independent-Music Scene Samuel C. Allen The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Samuel C. Allen 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Community-Based Research Commons Recommended Citation Allen, Samuel C., "Treasuries of Subcultural Capital: Three Indie Institutions in the London, Ontario Independent-Music Scene" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1460. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1460 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TREASURIES OF SUBCULTURAL CAPITAL: THREE INDIE INSTITUTIONS IN THE LONDON, ONTARIO INDEPENDENT-MUSIC SCENE (Thesis format: Monograph) by Samuel Charles Allen Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Popular Music and Culture The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Samuel Charles Allen 2013 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the role institutions play within the London, Ontario independent-music scene. Institutions are where indie-music scenes happen (Kruse 2003). -

Annual Report 2007 Creating and Distributing Top-Quality News, Sports and Entertainment Around the World

Annual Report 2007 Creating and distributing top-quality news, sports and entertainment around the world. News Corporation As of June 30, 2007 Filmed Entertainment WJBK Detroit, MI Latin America United States KRIV Houston, TX Cine Canal 33% Fox Filmed Entertainment KTXH Houston, TX Telecine 13% Twentieth Century Fox Film KMSP Minneapolis, MN Australia and New Zealand Corporation WFTC Minneapolis, MN Premium Movie Partnership 20% Fox 2000 Pictures WTVT Tampa Bay, FL Fox Searchlight Pictures KSAZ Phoenix, AZ Cable Network Programming Fox Atomic KUTP Phoenix, AZ United States Fox Music WJW Cleveland, OH FOX News Channel Twentieth Century Fox Home KDVR Denver, CO Fox Cable Networks Entertainment WRBW Orlando, FL FX Twentieth Century Fox Licensing WOFL Orlando, FL Fox Movie Channel and Merchandising KTVI St. Louis, MO Fox Regional Sports Networks Blue Sky Studios WDAF Kansas City, MO (15 owned and operated) (a) Twentieth Century Fox Television WITI Milwaukee, WI Fox Soccer Channel Fox Television Studios KSTU Salt Lake City, UT SPEED Twentieth Television WBRC Birmingham, AL FSN Regency Television 50% WHBQ Memphis, TN Fox Reality Asia WGHP Greensboro, NC Fox College Sports Balaji Telefilms 26% KTBC Austin, TX Fox International Channels Latin America WUTB Baltimore, MD Big Ten Network 49% Canal Fox WOGX Gainesville, FL Fox Sports Net Bay Area 40% Asia Fox Pan American Sports 38% Television STAR National Geographic Channel – United States STAR PLUS International 75% FOX Broadcasting Company STAR ONE National Geographic Channel – MyNetworkTV STAR -

PRESS 2007 Eimear Mckeith, 'The Island Leaving The

PRESS 2007 Eimear McKeith, 'The island leaving the art world green with envy', Sunday Tribune, Dublin, Ireland, 30 December 2007 Fiachra O'Cionnaith, 'Giant Sculpture for Docklands gets go-ahead', Evening Herald, Dublin, Ireland, 15 December 2007 Colm Kelpie, '46m sculpture planned for Liffey', Metro, Dublin, Ireland, 14 December 2007 Colm Kelpie, 'Plans for 46m statue on river', Irish Examiner, Dublin, Ireland, 14 December 2007 John K Grande, 'The Body as Architecture', ETC, Montreal, Canada, No. 80, December 2007 - February 2008 David Cohen, 'Smoke and Figures', The New York Sun, New York, USA, 21 November 2007 Leslie Camhi, 'Fog Alert', The Village Voice, New York, USA, 21 - 27 November 2007 Deborah Wilk, 'Antony Gormley: Blind Light', Time Out New York, New York, USA, 15 - 21 November 2007 Author Unknown, 'Blind Light: Sean Kelly Gallery', The Architect's Newspaper, New York, USA, 14 November 2007 Francesca Martin, 'Arts Diary', Guardian, London, England, 7 November 2007 Will Self, 'Psycho Geography: Hideous Towns', The Independent Magazine, The Independent, London, England, 3 November 2007 Brian Willems, 'Bundle Theory: Antony Gormley and Julian Barnes', artUS, Los Angeles, USA, Issue 20, Winter 2007 Author Unknown, 'Antony Gormley: Blind Light', Artcal.net, 1 November 2007 '4th Annual New Prints Review', Art on Paper, New York, USA, Vol. 12, No. 2, November-December 2007 Albery Jaritz, 'Figuren nach eigenem Gardemaß', Märkische Oderzeitung, Berlin, Germany, 23 October 2007 Author Unknown, 'Der Menschliche Körper', Berliner Morgenpost, Berlin, Germany, 18 October 2007 Albery Jaritz, 'Figuren nach eigenem Gardemaß', Lausitzer Rundschau, Berlin, Germany, 6 October 2007 Natalia Marianchyk, 'Top World Artists come to Kyiv', What's on, Kyiv, Ukraine, No. -

A70 Pkit 4.Pdf

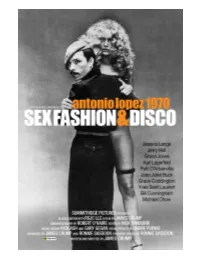

PRESS KIT Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex Fashion & Disco A Film by James Crump Featuring: Jessica Lange, Grace Jones, Bob Colacello, Jerry Hall,Grace Coddington, Patti D’Arbanville, Karl Lagerfeld, Juan Ramos, Bill Cunningham, Jane Forth, Yves Saint Laurent, Donna Jordan, Paul Caranicas, Joan Juliet Buck, Corey Tippin and Michael Chow. Film soundtrack features music by: Donna Summer,Marvin Gaye, Evelyn “Champagne” King, Isaac Hayes,Curtis Mayfield, Chic and the Temptations. Summitridge Pictures and RSJC LLC present a film by James Crump. Edited by Nick Tamburri. Visual Effects by Andre Purwo. Cinematography by Robert O’Haire. Produced by James Crump and Ronnie Sassoon. Sex Fashion & Disco is a feature documentary-based time capsule concerning Paris and New York between 1969 and 1973 and viewed through the eyes of Antonio Lopez (1943-1987), the dominant fashion illustrator of the time, and told through the lives of his colorful and some-times outrageous milieu. A native of Puerto Rico and raised in The Bronx, Antonio was a seductive arbiter of style and glamour who, beginning in the 1960s, brought elements of the urban street and ethnicity to bear on a postwar fashion world desperate for change and diversity. Counted among Antonio’s discoveries— muses of the period—were unusual beauties such as Cathee Dahmen, Grace Jones, Pat Cleveland, Tina Chow, Jessica Lange, Jerry Hall and Warhol Superstars Donna Jordan, Jane Forth and Patti D’Arbanville among others. Antonio’s inner circle in New York during this period was also comprised of his personal and creative partner, Juan Ramos (1942-1995), also Puerto Rican-born and raised in Harlem, makeup artist Corey Tippin and photographer Bill Cunningham, among others. -

Where's the Criticality, Tracey? a Performative Stance Towards

Where’s the Criticality, Tracey? A Performative Stance Towards Contemporary Art Practice Sarah Loggie 2018 Colab Faculty of Design and Creative Technologies An exegesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Creative Technologies Karakia Timatanga Tukua te wairua kia rere ki ngā taumata Hai ārahi i ā tātou mahi Me tā tātou whai i ngā tikanga a rātou ma Kia mau kia ita Kia kore ai e ngaro Kia pupuri Kia whakamaua Kia tina! TINA! Hui e! TAIKI E! Allow one’s spirit to exercise its potential To guide us in our work as well as in our pursuit of our ancestral traditions Take hold and preserve it Ensure it is never lost Hold fast. Secure it. Draw together! Affirm! 2 This content has been removed by the author due to copyright issues Figure A-1 My Bed, Tracey Emin, 1998, Photo: © Tracey Emin/Tate, London 2018 R 3 Figure B-1, 18-06-14, Sarah Loggie, 2014, Photo: © Sarah Loggie, 2018 4 Abstract Tracey Emin’s bed is in the Tate Museum. Flanked by two portraits by Francis Bacon, My Bed (1998) is almost inviting. Displayed on an angle, it gestures for us to climb under the covers, amongst stained sheets, used condoms and empty vodka bottles - detritus of Emin’s life. This is not the first time My Bed has been shown in the Tate. The 2015-17 exhibitions of this work are, in a sense, a homecoming, reminiscent of the work’s introduction to the British public. -

May -12 1120- ﻤﻭﻗﻊ ﺍﻟﻘﺩﺱ 1

12- May -2011 ﻤﻭﻗﻊ ﺍﻟﻘﺩﺱ اﻟﺴﻔﺎرة اﻟﺴﻮرﻳﺔ ﻓﻲ ﻟﻨﺪن ﺗﻨﻔﻲ ﺳﻔﺮ أﺳﻤﺎء اﻷﺳﺪ إﻟﻰ ﺑﺮﻳﻄﺎﻧﻴﺎ….…..........................1 ﻤﻭﻗﻊ ﺸﻭﻜﻭﻤﺎﻜﻭ ﺑﻌﺪ ﻟﻘﺎﺋﻬﻢ ﻣﻊ اﻟﺴﻴﺪة أﺳﻤﺎء اﻷﺳﺪ.. أهﺎﻟﻲ اﻟﺸﻬﺪاء: ﻣﺮﺳﻮم ﺟﻤﻬﻮري ﻳﻀﻤﻦ ﺣﻘﻮﻗﻨﺎ..........2 ﺼﺤﻴﻔﺔ ﺍﻟﻭﻓﺩ ﺍﻟﻤﺼﺭﻴﺔ وراء آﻞ رﺋﻴﺲ ﻣﺨﻠﻮع .. اﻣﺮأة.......................................................................4 fashionistaﻤﻭﻗﻊ Vogue ‘Disappears’ Ill-Timed Profile of Syria’s First Lady..........................8 Jerusalem Post ﺼﺤﻴﻔﺔ 10000 Syrians reportedly in custody as death toll hits 750........................9 AFP UN agency suspends most Syria operations......................................13 ﺍﻟﺴﻔﺎﺭﺓ ﺍﻟﺴﻭﺭﻴﺔ ﻓﻲ ﻟﻨﺩﻥ ﺘﻨﻔﻲ ﺴﻔﺭ ﺃﺴﻤﺎﺀ ﺍﻷﺴﺩ ﺇﻟﻰ ﺒﺭﻴﻁﺎﻨﻴﺎ (ﺍﻟﻘﺩﺱ) ﻨﻔﺕ ﺍﻟﺴﻔﺎﺭﺓ ﺍﻟﺴﻭﺭﻴﺔ ﻓﻲ ﻟﻨﺩﻥ ﻤﺎ ﺭﺩﺩﺘﻪ ﻭﺴﺎﺌل ﺇﻋﻼﻡ ﺒﺭﻴﻁﺎﻨﻴﺔ ﻤﻥ "ﺸﺎﺌﻌﺎﺕ" ﺤﻭل ﺘﻭﺍﺠﺩ ﺴﻴﺩﺓ ﺴﻭﺭﻴﺔ ﺍﻷﻭﻟﻰ ﺃﺴﻤﺎﺀ ﺍﻷﺴﺩ ﻓﻲ ﺒﺭﻴﻁﺎﻨﻴﺎ. ﻭﻗﺎﻟﺕ ﺍﻟﺴﻔﺎﺭﺓ ﻓﻲ ﺒﻴﺎﻥ ﻟﻬﺎ، ﺇﻥ "ﺍﻟﺸﺎﺌﻌﺎﺕ" ﺍﻟﺨﺎﻁﺌﺔ ﺍﻟﺘﻲ ﺘﺩﺍﻭﻟﺘﻬﺎ ﺒﻌﺽ ﻭﺴﺎﺌل ﺍﻹﻋﻼﻡ ﺍﻟﺒﺭﻴﻁﺎﻨﻴﺔ ﻓﻴﻤﺎ ﻴﺘﻌﻠﻕ ﺒﻤﻜﺎﻥ ﺘﻭﺍﺠﺩ ﺃﺴﻤﺎﺀ ﺍﻷﺴﺩ ﻭﺃﺒﻨﺎﺌﻬﺎ ﺘﻬﺩﻑ ﺇﻟﻰ ﻋﺭﻗﻠﺔ ﻋﻤﻠﻴﺔ ﺍﻹﺼﻼﺡ ﺍﻟﺠﺎﺭﻴﺔ ﺤﺎﻟﻴﺎ ﻓﻲ ﺴﻭﺭﻴﺔ. ﻭﺫﻜﺭ ﺍﻟﺴﻔﻴﺭ ﺍﻟﺴﻭﺭﻱ ﻓﻲ ﻟﻨﺩﻥ ﺴﺎﻤﻲ ﺍﻟﺨﻴﻤﻲ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺒﻴﺎﻥ ﺃﻥ ﺃﺴﻤﺎﺀ ﺍﻷﺴﺩ ﻭﺃﺒﻨﺎﺀﻫﺎ ﺍﻟﺜﻼﺜﺔ ﻟﻴﺴﻭﺍ ﻓﻲ ﺒﺭﻴﻁﺎﻨﻴﺎ ، ﻤﺅﻜﺩﺍ ﺃﻥ ﺍﻟﺴﻴﺩﺓ ﺍﻟﺴﻭﺭﻴﺔ ﺍﻷﻭﻟﻰ ﻤﺘﻭﺍﺠﺩﺓ ﻓﻲ ﺩﻤﺸﻕ ، ﻭﺘﺭﻜﺯ ﻋﻠﻰ ﺘﻨﺎﻭل ﺍﻟﻘﻀﺎﻴﺎ ﺍﻟﺩﺍﺨﻠﻴﺔ ، ﺒﻤﺎ ﻓﻲ ﺫﻟﻙ ﺒﺭﻨﺎﻤﺠﻬﺎ ﺒﺸﺄﻥ ﺘﻤﻜﻴﻥ ﺍﻟﺸﻌﺏ ﺍﻟﺴﻭﺭﻱ. ﻭﺸﺩﺩ ﺍﻟﺴﻔﻴﺭ ﻋﻠﻰ ﺃﻥ ﺃﺒﻨﺎﺀﻫﺎ ﻓﻲ ﺩﻤﺸﻕ ﺃﻴﻀﺎ ، ﻭﻻ ﻴﺤﻤﻠﻭﻥ ﺴﻭﻯ ﺠﻭﺍﺯ ﺴﻔﺭ ﺴﻭﺭﻱ ، ﻋﻠﻰ ﻋﻜﺱ ﻤﺎ ﺭﺩﺩﺘﻪ ﻫﺫﻩ ﺍﻟﺸﺎﺌﻌﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻐﺭﻀﺔ ، ﻋﻠﻰ ﺤﺩ ﺘﻌﺒﻴﺭﻩ. ﻭﺃﻜﺩ ﺍﻟﺨﻴﻤﻲ ﻋﻠﻰ ﺃﻥ ﻋﻘﻴﻠﺔ ﺍﻟﺭﺌﻴﺱ ﺍﻟﺴﻭﺭﻱ ﺒﺸﺎﺭ ﺍﻷﺴﺩ ﻟﻥ ﺘﻐﺎﺩﺭ ﺴﻭﺭﻴﺔ ﺘﺤﺕ ﺃﻱ ﻅﺭﻑ ﺃﺜﻨﺎﺀ ﺇﺠﺭﺍﺀ ﻋﻤﻠﻴﺔ ﺍﻹﺼﻼﺡ ﻭﺍﻟﺘﻁﻭﻴﺭ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺒﻼﺩ ، ﻤﺸﻴﺭﺍ ﺇﻟﻰ ﺃﻥ ﺍﻟﻘﻴﺎﺩﺓ ﺍﻟﺴﻭﺭﻴﺔ ﺒﺎﻟﻜﺎﻤل ﺘﺴﺘﺠﻴﺏ ﻟﻠﻤﻁﺎﻟﺏ ﺍﻟﻤﺸﺭﻭﻋﺔ ﻟﻠﺸﻌﺏ ﻤﻥ ﺨﻼل ﺘﺒﻨﻲ ﺃﺠﻨﺩﺓ ﺇﺼﻼﺤﺎﺕ ﻁﻤﻭﺤﺔ. ﻭﺃﻭﻀﺢ ﺃﻥ ﺃﺴﻤﺎﺀ ﺍﻷﺴﺩ ﺘﺒﺫل ﺠﻬﻭﺩﺍ ﺤﺜﻴﺜﺔ ، ﻭﺘﻌﻘﺩ ﺍﺠﺘﻤﺎﻋﺎﺕ ﻤﻊ ﻗﺎﺩﺓ ﺍﻟﻤﺠﺘﻤﻊ ﺍﻟﻤﺩﻨﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﺠﻤﺎﻋﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﺸﺒﺎﺒﻴﺔ ﻟﻤﻨﺎﻗﺸﺔ ﺁﻤﺎﻟﻬﻡ ﻭﺘﻭﻗﻌﺎﺘﻬﻡ ﺒﺸﺄﻥ ﻤﺴﺘﻘﺒل ﺍﻟﺒﻼﺩ. ﻭﻗﺎل ﺍﻟﺒﻴﺎﻥ ﺇﻨﻪ ﺘﻠﺒﻴﺔ ﻟﻠﻤﻁﺎﻟﺏ ﺍﻟﺸﻌﺒﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﺘﻲ ﺘﻨﺎﺩﻱ ﺒﺎﻹﺼﻼﺡ ، ﺃﻟﻐﺕ ﺍﻟﻘﻴﺎﺩﺓ ﺍﻟﺴﻭﺭﻴﺔ ﻗﺎﻨﻭﻥ ﺍﻟﻁﻭﺍﺭﺉ ﻭﺸﻜﻠﺕ ﺤﻜﻭﻤﺔ ﺠﺩﻴﺩﺓ ﺘﻬﺩﻑ ﺇﻟﻰ ﺇﺠﺭﺍﺀ ﺇﺼﻼﺤﺎﺕ ﻭﺃﻓﺭﺠﺕ ﻋﻥ ﻤﻌﺘﻘﻠﻴﻥ ﻭﺍﺘﺨﺫﺕ ﺇﺠﺭﺍﺀﺍﺕ ﺠﺭﻴﺌﺔ ﺃﺨﺭﻯ ﺘﻬﺩﻑ ﺇﻟﻰ ﺘﻠﺒﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻤﻁﺎﻟﺏ ﺍﻟﻤﺸﺭﻭﻋﺔ ﻟﻠﺸﻌﺏ ، ﻋﻠﻰ ﺤﺩ ﻗﻭﻟﻪ. -

Luis Gispert

LUIS GISPERT Born 1972 | Lives and works in Brooklyn NY, USA EDUCATION 2001 MFA, Sculpture, Yale University, New Haven CT, USA 1996 BFA, Film, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago IL, USA 1994 Miami Dade College FL, USA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Landline | MAKASIINI CONTEMPORARY, Turku, Finland 2016 Between Us and The World | Zidoun-Bossuyt, Luxembourg 2015 Aqua Regia | Moran Bondaroff Gallery, Los Angeles CA, USA Block Watcing | Landmarks, University of Texas at Austin, Austin Texas TX, USA 2014 Reckon Without | Mallorca Landings, Palma de Mallorca, Spain Tender Game | David Castillo Gallery, Miami FL, USA 2013 Antena | Mendes Wood Galllery, São Paulo, Brazil 2012 All Oyster, No Pearl | OHWOW Gallery, Los Angeles CA, USA Pin, Pan, Pun | Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago IL, USA 2011 Decepcion | Mary Boone Gallery, New York NY, USA Decepcion | Mallorca Landings, Palma de Mallorca, Spain Centre Cultural Contemporani Pelaires, Palma de Mallorca, Spain 2010 Galerie Zidoun, Luxembourg 2009 Luis Gispert | Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami FL, USA Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago IL, USA Otereo Plassert Gallery, Los Angeles CA, USA 2008 Heavy Manner | Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami FL, USA El Mundo Es Tuyo (the world is yours) | Zach Feuer Gallery El Mundo Es Tuyo (the world is yours) | Mary Boone Gallery, New York NY, USA 2005 Luis Gispert & Jeffrey Reed: Stereomongrel | The Whitney Museum, New York NY, USA Luis Gispert & Jeffrey Reed: Stereomongrel | Zach Feuer Gallery (LFL), New York NY, USA Luis Gispert & Jeffrey Reed: Stereomongrel |