Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographies Page 1 of 2

Pearson Prentice Hall: Biographies Page 1 of 2 Biographies Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) "They that can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety." —Historical Review of Pennsylvania , 1759 One of Benjamin Franklin's contemporaries, the French economist Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, once described Franklin's remarkable achievements in the following way: "He snatched the lightning from the skies and the sceptre from tyrants." Printer The son of a Boston soap- and candle-maker, Benjamin Franklin had little formal education, but he read widely and practiced writing diligently. He was apprenticed to his brother, a printer, at the age of 12. Later, he found work as a printer in Philadelphia. Courtesy Library of Congress By the time he was 20, Franklin and a partner owned a company that printed the paper currency of Pennsylvania. Franklin also published a newspaper and, from 1732 to 1757, his famous Poor Richard's Almanac . Public Service Franklin was always interested in improving things, from the way people lived lives to the way they were governed. In 1727, he founded the Junto, a society that debated questions of the day. This, in turn, led to the establishment of a library association and a volunteer fire company in Philadelphia. He was also instrumental in founding the University of Pennsylvania. In addition, Franklin spent time conducting scientific experiments involving electricity and inventing useful objects, such as the lightning rod, an improved stove, and bifocals. Franklin was also active in politics. He served as clerk of the Pennsylvania legislature and postmaster of Philadelphia, and he organized the Pennsylvania militia. -

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin Benjamin Franklin FRS FRSA FRSE (January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6, 1705][Note 1] – April 17, 1790) was a British American polymath and one of the Founding Fathers of the Benjamin Franklin United States. Franklin was a leading writer, printer, political philosopher, politician, FRS, FRSA, FRSE Freemason, postmaster, scientist, inventor, humorist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat. As a scientist, he was a major figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics for his discoveries and theories regarding electricity. As an inventor, he is known for the lightning rod, bifocals, and the Franklin stove, among other inventions.[1] He founded many civic organizations, including the Library Company, Philadelphia's first fire department,[2] and the University of Pennsylvania.[3] Franklin earned the title of "The First American" for his early and indefatigable campaigning for colonial unity, initially as an author and spokesman in London for several colonies. As the first United States ambassador to France, he exemplified the emerging American nation.[4] Franklin was foundational in defining the American ethos as a marriage of the practical values of thrift, hard work, education, community spirit, self- governing institutions, and opposition to authoritarianism both political and religious, with the scientific and tolerant values of the Enlightenment. In the words of historian Henry Steele Commager, "In a Franklin could be merged the virtues of Puritanism without its Benjamin Franklin by Joseph defects, the illumination -

Mary Brackett Willcox Papers MC 10 Finding Aid Prepared by Faith Charlton and Heather Schubert

Mary Brackett Willcox papers MC 10 Finding aid prepared by Faith Charlton and Heather Schubert. Last updated on November 04, 2015. Philadelphia Archdiocesan Historical Research Center ; December 2011 Mary Brackett Willcox papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Other Finding Aids........................................................................................................................................9 Publication note............................................................................................................................................. 9 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................9 -

Abou T B En Fran Klin

3 Continuing Eventsthrough December 31,2006 January 17– March 15, 2006 LEAD SPONSOR B F o O u f O o nding Father nding r KS 1 In Philadelphia EVERYONE IS READING about Ben Franklin www.library.phila.gov The Autobiography Ben and Me Franklin: The Essential of Benjamin Franklin BY ROBERT LAWSON Founding Father RBY BENeJAMIN FRAsNKLIN ource BY JAGMES SRODES uide One Book, One Philadelphia The Books — Three Books for One Founding Father In 2006, One Book, One Philadelphia is joining Ben Franklin 300 Philadelphia to celebrate the tercentenary (300 years) of Franklin’s birth. Franklin’s interests were diverse and wide-ranging. Countless volumes have been written about him. The challenge for the One Book program was to choose works that would adequately capture the true essence of the man and his times. Because of the complexity of this year’s subject, and in order to promote the widest participation possible, One Book, One Philadelphia has chosen to offer not one, but three books about Franklin. This year’s theme will be “Three Books for One Founding Father.” The featured books are: • The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin by Benjamin Franklin (various editions) • Ben and Me by Robert Lawson (1939, Little, Brown & Company) • Franklin: The Essential Founding Father by James Srodes (2002, Regnery Publishing, Inc.) The Authors BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, author of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, was born in 1706 and died in 1790 at the age of 84. He was an author, inventor, businessman, scholar, scientist, revolutionary, and statesman whose contributions to Philadelphia and the world are countless. -

Friendship Fire Company: 117 South Market Street; Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania

Hon 170: Elizabethtown History: Campus and Community Joseph C. Rue Professor Benowitz 5 May 2017 Friendship Fire Company: 117 South Market Street; Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania Abstract: The Friendship Fire Company building, located at 117 South Market Street in Elizabethtown, PA, was originally used as a firehouse. It was built in 1884, on land willed to Mary Breneman by Elizabeth Redsecker, who inherited it from her father George. The Friendship Fire Company building was a larger and more centralized location for The Friendship Fire Engine and Hose Co. No. 1 of Elizabethtown, which was founded in 1836 and previously housed on Poplar Street. The building was decommissioned by the fire department in 1976, and is currently a gallery and frame shop. The original Victorian brick facade was covered over with the current stucco in the 1920s. There was a wood-frame structure on the property in the 1840s when it was sold to Jacob Gish, which before that was operated as a hotel. Property Details: The Friendship Fire Company building is located at 117 South Market Street in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania 17022 Lancaster County.1 The current structure, which was constructed in 1884 by Benjamin G. Groff,2 is situated on a 33 by 196 foot lot (approximately 6,534 square feet).3 There was previously a structure which was operated as a hotel on this lot.4 Deed Search: The current community of Elizabethtown is situated between the Conoy Creek and the Conwego Creek along the Susquehanna River. In 1534 French King Francis, I (1494-1547) colonized North America establishing New France with Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) as Viceroy in Quebec.5 As early as 1615 Étienne 1 Lancaster Property Tax Inquiry, Parcel: 2507127200000, accessed 7 May 2017, http://lancasterpa.devnetwedge.com/parcel/view/2507127200000/2017. -

Amazingmrfranklin.Pdf

TheThe Amazing r.r. ranklin or The Boy Who Read Everything To Ernie —R.A. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2004 by Ruth Ashby Illustrations © 2004 by Michael Montgomery All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Composition by Melanie McMahon Ives Paintings created in oil on canvas Text typeset in SWFTE International’s Bronte; titles typeset in Luiz da Lomba’s Theatre Antione Printed in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ashby, Ruth. The amazing Mr. Franklin / written by Ruth Ashby.-- 1st ed. p. cm. Summary: Introduces the life of inventor, statesman, and founding father Benjamin Franklin, whose love of books led him to establish the first public library in the American colonies. ISBN 978-1-56145-306-1 1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790--Juvenile literature. 2. Statesmen--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. 3. Scientists--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. 4. Inventors--United States-- Biography--Juvenile literature. 5. Printers--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. [1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790. 2. Statesmen. 3. Scientists. 4. Inventors. 5. Printers.] I. Title. E302.6.F8A78 2004 973.3'092--dc22 -

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He is famous for many reasons. He was a politician, a scientist, an inventor, an author, and a statesman. He was the youngest son in a family with 17 children. Benjamin Franklin started out as an apprentice in his brother's print shop in Boston, and he created The New-England Courant, which was the first truly independent newspaper in the colonies. He wanted to write for the paper, but was not permitted to do so. Benjamin Franklin used a pseudonym to write for the paper. A pseudonym is a fictitious name used in place of a person's real name. He used the pseudonym of “Mrs. Silence Dogood,” who was supposedly a middle-aged widow. His letters were published in the paper and became a topic of discussion around town. His brother did not know that Benjamin was actually writing the letters and was upset when he learned the truth. When he was only 17, Benjamin Franklin wound up running away to Philadelphia to seek a new start in life. In 1733, Benjamin Franklin began publishing Poor Richard's Almanac. He wrote some of the material himself and also used material from other sources. He used the pseudonym Richard Saunders to publish this work, and he sold about 10,000 copies per year. As an inventor, Ben Franklin accomplished many things. He invented the lightning rod, the glass harmonica, the Franklin stove, and bifocals. In 1743, he founded the American Philosophical Society, which was designed to help men discuss their theories and discoveries. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

Franklin Handout

The Lives of Benjamin Franklin Smithsonian Associates Prof. Richard Bell, Department of History University of Maryland Richard-Bell.com [email protected] Try Your Hand at a Franklin Magic Square Complete this magic square using the numbers 1 to 16 (the magic number is 34 The Lives of Benjamin Franklin: A Selective Bibliography Bibliography prepared by Dr. Richard Bell. Introducing Benjamin Franklin - H.W. Brands, The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (2000) - Carl Van Doren, Benjamin Franklin (1938) - Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (2003) - Leonard W Labaree,. et al., eds. The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (1959-) - J. A. Leo Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 1, Journalist, 1706–1730 (2005). - J. A. Leo Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 2, Printer and Publisher, 1730–1747 (2005) - J. A. Leo Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 3, Soldier, Scientist and Politician, 1748-1757 (2008) - Edmund S. Morgan, Benjamin Franklin (2002) - Carla Mulford, ed, Cambridge Companion to Benjamin Franklin (2008) - Page Talbott, ed., Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World (2005) - David Waldstreicher, ed., A Companion to Benjamin Franklin (2011) - Esmond Wright, Franklin of Philadelphia (1986) Youth - Douglas Anderson, The Radical Enlightenments of Benjamin Franklin (1997) - Benjamin Franklin the Elder, Verses and Acrostic, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin Digital Edition http://franklinpapers.org/franklin/ (hereafter PBF), I:3-5 - BF (?) ‘The Lighthouse Tragedy’ and ‘The Taking of Teach the Pirate,’ PBF, I:6-7 - Silence Dogood, nos. 1, 4, PBF, I:8, I:14 - BF, A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity (1725), PBF, I:57 - BF, ‘Article of Belief and Acts of Religion,’ PBF, I:101 - David D. -

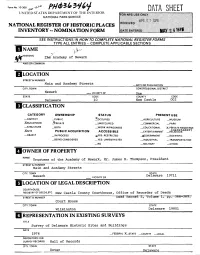

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building. -

Citation: Lawson, a (2020) Becoming Bourgeois: Benjamin Franklin's

Citation: Lawson, A (2020) Becoming Bourgeois: Benjamin Franklin’s Account of the Self. English Literary History, 87 (2). pp. 463-489. ISSN 0013-8304 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/6004/ Document Version: Article (Accepted Version) Copyright c 2020 Johns Hopkins University Press The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law. The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team. We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Each thesis in the repository has been cleared where necessary by the author for third party copyright. If you would like a thesis to be removed from the repository or believe there is an issue with copyright, please contact us on [email protected] and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Becoming Bourgeois: Benjamin Franklin’s Account of the Self In 1746 Benjamin Franklin had his portrait painted by the Boston artist Robert Feke (Figure 1). Franklin wears a light wig and a dark velvet coat, a ruffled silk shirt adding a hint of finery. He stands “erect and assured, his head cocked to one side, his right hand open to his side in a gesture that traditionally suggests the power to dispose of matters by a wave of the hand.”1 Franklin was already a successful printer and bookseller, the owner of the Pennsylvania Gazette and the bestselling Poor Richard’s Almanac. -

Introduction: the 1737 Accounts Provide a Series of Glimpses Into BF's Day-To-Day Family Life

Franklin’s Accounts, 1737, Calendar 7. 1 Introduction: The 1737 accounts provide a series of glimpses into BF’s day-to-day family life. On one occasion (the only one for which we have any evidence), BF spoke sharply to Deborah concerning her careless bookeeping. Since the most expensive paper cost several times more than the cheapest, it was important to record either the price or the kind of paper. Deborah sold a quire of paper to the schoolteacher and poet William Satterthwaite on 15 Aug and did not record or remember what kind. After Franklin spoke to her, Deborah, in frustration, exasperation, and chagrin, recorded his words or the gist of them in the William Satterthwaite entry: “a Quier of paper that my Carles Wife for got to set down and now the carles thing donte now the prise sow I muste truste to you.” If she recorded the words exactly, BF may have spoken to Satterthwaite in her presence. That possibility, however, seems unlikely. I suspect that an irritated BF told her that he would have to ask Satterthwaite what kind of paper. One wonders if he had said anything to her earlier about the following minor charge: “Reseved of Ms. Benet 2 parchment that wass frows and shee has a pound of buter and 6 pens in money, 1.6., and sum flower but I dont now [know] what it cums to” (14 Feb). Franklin’s brother James died in 1735, and by 1737 BF was giving his sister-in-law Ann Franklin free supplies and imprints (21 and 28 May), for he did not bother to enter the amount.