Mining Soul Deep a Lesson in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

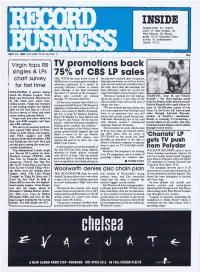

Record-Business-1982

INSIDE Singles chart, 6-7; Album chart, 17; New Singles, 18; New Albums 9; Airplay guide, 14-15; Independent Labels, 8; Country Music Focus,12-13. April 5, 1982 VOLUME FIVENumber 2 65p 56 staff given Record wholesalers' notice at EMI's video success story World Records IN STARK contrast to their retailing area of business. "It will never take mail order co. counterparts record wholesalers areover the record side and we wouldn't leading the move into video and mostwant it to but it is a valuable line," said WORLD RECORDS, EMI'smail are well placed to take advantage of theBrian Yershon, video marketing man- order arm, will be sold or merged with expected boom. ager. another direct mail company within the While the video -only wholesalers "In 1982 we are primarily a record next few months. eye the horizon with some trepidationwholesaler but we seefiveyears The company, which began 25 years the record/video outfits, particularlygrowth in the video industry. We are ago, was moved out of its Richmond the big four - Wynd-Up, Terry Blood,seeing growth on both sides and I think offices last year and re -settled at the S. Gold & Sons and Warrens - arethat records and videos are natural main EMI factory complex at Uxbridge looking for growth. bedfellows," said Colin Reilly, Wynd- Road, Hayes. The 56 staff were told last All these companies plus LightningUp chief executive. As a main board week that talks were taking place with (whose recent name change to Light-director of NSS he is also sure that other companies interested in either ning Records & Video indicates itsvideo is a promising retail growth area. -

Record-Business-1982

INSIDE Singles chart, 6-7; Album chart, 17; New Singles, 18; New Albums, 19; Airplay guide, 15-15; Quarterly Chart survey, 12; Independent Labels, 12/13. April 12, 1982VOLUME FIVE Number 3 65p Virgin tops RBTV promotions back singles & LPs 75% of CBS LP sales chart survey CBS, WITH the most active roster ofthe industry's national chart was gained, MOR artists, is increasingly resorting toalthough promotion on such an intense television promotion asa means ofscale was not underway anywhere else at for first time securing sufficient volume to ensurethe time. Since then the campaign has chart placings. It has been estimatedbeen efficiently rolled out to give the FOLLOWING A quarter during that about 75 percent of the company'ssinger her highest chart placing to date. which the Human League, Toni albumsalescurrentlyarecoming Television backing for the IglesiasTIGHTFIT, keepfitand Felicity Basil and Orchestral Manoeuvres through TV -boosted repertoire. album has given it a new lease of lifeKendall - the chart -topping group In The Dark were major best- after an earlier chart entry at the time offrom the Zomba stable present actress selling artists, Virgin has emerged Of the seven releases with which it is scoring in the RB Top 60, CBS has givenrelease last year. Felicity Kendall with a gold album for as the leading singles and albums "We are certainly getting volume, butsales of 200,000 -plus copies of her label for the first time in a Record significant smallscreen support to five of them, Love Songs by Barbra Streisand,it is a very expensive way of doing it andShape Up And Dance LP, sold on mail Business survey of chart and sales there is no guarantee that you willorderthroughLifestyleRecords, action during January -March. -

Paul Weller with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Jules Buckley

For immediate release Paul Weller with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Jules Buckley concert date added to ‘Live from the Barbican’ line-up in spring 2021 Barbican Hall, Saturday 6 February 2021, 8pm The Barbican and Barbican Associate Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra are excited to announce that the orchestra and its Creative Artist in Association Jules Buckley, will be joined by legendary singer songwriter Paul Weller on Saturday 6 February for a concert reimagining Weller’s work in stunning orchestral settings as part of Live from the Barbican in 2021. In Weller’s first live performance for two years, songs spanning the broad spectrum of his career from The Jam to as yet unheard new material will delight fans and newcomers alike. Classic songs including ‘You Do Something to Me’, ‘English Rose’ and ‘Wild Wood’ along with tracks from Weller’s latest number 1 album ‘On Sunset’ will be heard as never before in brand new orchestral arrangements by Buckley. Weller, who takes cultural authenticity to the top of the charts, reunites with Steve Cradock for this one-off performance. Part of the acclaimed Live from the Barbican series which returns to the Centre in the spring, the concert will have a reduced, socially distanced live audience in the Barbican Hall, and it will also be available to watch globally via a livestream on the Barbican website. Whilst the concert will reflect on some of Weller’s back catalogue, as is typical of his constantly evolving career, it will look to the future with performances of songs from an album not released until May 2021, as well as welcoming guest artists to illustrate his work and the music that influenced him. -

The Style Council Gold Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Style Council Gold mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock / Reggae / Funk / Soul / Pop Album: Gold Country: Philippines Released: 2006 Style: Brit Pop, Soul, Mod MP3 version RAR size: 1256 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1691 mb WMA version RAR size: 1494 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 503 Other Formats: DMF MP1 DXD MP4 APE DMF MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits You're The Best Thing 1.01 Written By – Paul Weller A Stones Throw Away 1.02 Written By – Paul Weller Have You Ever Had It Blue 1.03 Written By – Paul Weller Blue Cafe 1.04 Written By – Paul Weller Money Go Round (Parts 1 & 2) 1.05 Written By – Paul Weller Headstart For Happiness 1.06 Written By – Paul Weller My Ever Changing Moods 1.07 Written By – Paul Weller Here's One That Got Away 1.08 Written By – Paul Weller Long Hot Summer 1.09 Written By – Paul Weller Internationalists 1.10 Written By – Mick Talbot, Paul Weller Man Of Great Promise 1.11 Written By – Paul Weller Our Favorite Shop 1.12 Written By – Mick Talbot The Lodgers 1.13 Written By – Mick Talbot, Paul Weller Walls Come Tumbling Down 1.14 Written By – Paul Weller The Cost Of Loving 1.15 Written By – Paul Weller Wanted 1.16 Written By – Mick Talbot, Paul Weller The Paris Match 1.17 Written By – Paul Weller The Big Boss Groove 1.18 Written By – Mick Talbot, Paul Weller It Didn't Matter 2.01 Written By – Paul Weller, Paul Weller The Whole Point Of No Return 2.02 Written By – Paul Weller Speak Like A Child 2.03 Written By – Paul Weller Why I Went Mising 2.04 Written By – Paul Weller A Solid Bond In Your Heart -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

Royalty Court Chosen Nursing Awaits Inaugural Year

October 4, 1985 Volume 78 CONCORDIAN Number 5 Concordia College Moorhead, Minn. Royalty court chosen an English major with minors in philosophy and by Jill C. Otterson business administration. He has been involved in news reporter Temple Band, choir, and he has been an Orienta- tion club communicator. Homecoming festivities for Concordia College are The Queen candidates are: drawing near. Everything is ready and it will all begin on Sunday, October 6. Christine Daines, from Bozeman, Montana. She is an international business and French double ma- Coronation of the Homecoming Queen and King jor. Christine's activities include Religion Commis- will take place on Sunday. The King and Queen sion, Concert Choir, and Orientation club will reign over the festivities throughout the week. communicator. Ten seniors were chosen by the student body on Sept. 30 as royal homecoming, finalists. Front row: Tori Gabrielson, Christie Daines, Karen Wickstrom, Ann Rimmereid, The finalists for Homecoming King and Queen are Tori Gabriejson, a native of Lodi, California, is a as" follows: business administration and French double major. Rachel Hanson. Back row: Dan Ankerfelt, Tom Madson, Dave Milbrandt, Craig Snelt- Religion Commission, aerobics, Campus Life, in- jes, Randy Curtiss. Dan Ankerfelt, from Glencoe, Minnesota. A tramurals, Ah-Ker and the Big Brother/Big Sister psychology major with minors in music and religion, program keep her busy. Dan has been involved in Freshman Choir, Chapel Choir, Band, Orchestra, fellowship teams, and is Rachel Hanson is from Minneapolis, Minesota, and president of Mu Phi Epsilon. is involved in choir, Outreach, and dorm staff. She is a biology major with minors in both chemistry Bismarck, North Dakota, is home to Randy Cur- and psychology. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

George Michael Was Britain's Biggest Pop Star of the 1980S, First with The

George Michael was Britain’s biggest pop star of the 1980s, first with the duo Wham! and then as a solo artist. The Three Crowns played a small but significant part in his story. After Wham! made their initial chart breakthrough with the single Young Guns (Go for It) in 1982, George’s songwriting gift brought them giant hits including Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go and Freedom, and they became leading lights of the 80s boom in British pop music, alongside Duran Duran, Culture Club and Spandau Ballet, even exporting it behind the Iron Curtain. His first solo album Faith, released in 1987, sold 25 million copies, and George sold more than 100 million albums worldwide with Wham! and under his own name. George was born Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou in Finchley, north London. His father, Kyriacos Panayiotou, was a Greek Cypriot restaurateur, and his mother an English dancer, Lesley Angold. In the late 1960s the family moved to Edgware, where George attended Kingsbury School, before they moved to the affluent Hertfordshire town of Radlett in the mid-1970s. Bushey Meads Comprehensive 1974 - 1981 George – a wimp Andy - cocksure In September 1975 a twelve year old George showed up at Bushey Meads School keen to impress as the new boy and was introduced to Andy Ridgeley who had already been impressing for a full year. Andy recalled their meeting as follows; “I remember at the time we were playing King of the Wall. As he was the new boy we goaded him into it. I was up there and he threw me off. -

KARAOKE Buch 2019 Vers 2

Wenn ihr euer gesuchtes Lied nicht im Buch findet - bitte DJ fragen Weitere 10.000 Songs in Englisch und Deutsch auf Anfrage If you can’t find your favourite song in the book – please ask the DJ More then 10.000 Songs in English and German toon request 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 4 Non Blondes What's Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 5th Dimension Aquarius & Let The Sunshine A Ha Take On Me Abba Dancing Queen Abba Gimme Gimme Gimme Abba Knowing Me, Knowing You Abba Mama Mia Abba Waterloo ACDC Highway To Hell ACDC T.N.T ACDC Thunderstruck ACDC You Shook Me All Night Long Ace Of Base All That She Wants Adele Chasing Pavements Adele Hello Adele Make You Feel My Love Adele Rolling In The Deep Adele Skyfall Adele Someone Like You Adrian (Bombay) Ring Of Fire Adrian Dirty Angels Adrian My Big Boner Aerosmith Dream On Aerosmith I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing Afroman Because I Got High Air Supply All Out Of Love Al Wilson The Snake Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alannah Miles Black Velvet Alcazar Crying at The Discotheque Alex Clare Too Close Alexandra Burke Hallelujah Alice Cooper Poison Alice Cooper School’s Out Alicia Keys Empire State Of Mind (Part 2) Alicia Keys Fallin’ Alicia Keys If I Ain’t Got You Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal Alison Moyet That Old Devil Called Love Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Alphaville Big In Japan Ami Stewart Knock On Wood Amy MacDonald This Is The Life Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Rehab Amy Winehouse Valerie Anastacia I’m Outta Love Anastasia Sick & Tired Andy Williams Can’t Take My Eyes Off Of You Animals, The The House Of The Rising Sun Aqua Barbie Girl Archies, The Sugar, Sugar Arctic Monkeys I Bet You Look Good On The Dance Floor Aretha Franklin Respect Arrows, The Hot Hot Hot Atomic Kitten Eternal Flame Atomic Kitten Whole Again Avicii & Aloe Blacc Wake Me Up Avril Lavigne Complicated Avril Lavigne Sk8er Boi Aztec Camera Somewhere In My Heart Gesuchtes Lied nicht im Buch - bitte DJ fragen B.J. -

Eyez on Me 2PAC – Changes 2PAC - Dear Mama 2PAC - I Ain't Mad at Cha 2PAC Feat

2 UNLIMITED- No Limit 2PAC - All Eyez On Me 2PAC – Changes 2PAC - Dear Mama 2PAC - I Ain't Mad At Cha 2PAC Feat. Dr DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN - California Love 311 - Amber 311 - Beautiful Disaster 311 - Down 3 DOORS DOWN - Away From The Sun 3 DOORS DOWN – Be Like That 3 DOORS DOWN - Behind Those Eyes 3 DOORS DOWN - Dangerous Game 3 DOORS DOWN – Duck An Run 3 DOORS DOWN – Here By Me 3 DOORS DOWN - Here Without You 3 DOORS DOWN - Kryptonite 3 DOORS DOWN - Landing In London 3 DOORS DOWN – Let Me Go 3 DOORS DOWN - Live For Today 3 DOORS DOWN – Loser 3 DOORS DOWN – So I Need You 3 DOORS DOWN – The Better Life 3 DOORS DOWN – The Road I'm On 3 DOORS DOWN - When I'm Gone 4 NON BLONDES - Spaceman 4 NON BLONDES - What's Up 4 NON BLONDES - What's Up ( Acoustative Version ) 4 THE CAUSE - Ain't No Sunshine 4 THE CAUSE - Stand By Me 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Amnesia 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Don't Stop 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER – Good Girls 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Jet Black Heart 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER – Lie To Me 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - She Looks So Perfect 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Teeth 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - What I Like About You 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Youngblood 10CC - Donna 10CC - Dreadlock Holiday 10CC - I'm Mandy ( Fly Me ) 10CC - I'm Mandy Fly Me 10CC - I'm Not In Love 10CC - Life Is A Minestrone 10CC - Rubber Bullets 10CC - The Things We Do For Love 10CC - The Wall Street Shuffle 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Closer To The Edge 30 SECONDS TO MARS - From Yesterday 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Kings and Queens 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Teeth 30 SECONDS TO MARS - The Kill (Bury Me) 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Up In The Air 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Walk On Water 50 CENT - Candy Shop 50 CENT - Disco Inferno 50 CENT - In Da Club 50 CENT - Just A Lil' Bit 50 CENT - Wanksta 50 CENT Feat.