3 Cultural Mediators and Their Complex Transfer Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Nominees 2019"

• EUROPEAN UNION PRIZE FOR EUm1esaward CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE 19 MIES VAN DER ROHE Name Work country Work city Offices Pustec Square Albania Pustec Metro_POLIS, G&K Skanderbeg Square Albania Tirana 51N4E, Plant en Houtgoed, Anri Sala, iRI “New Baazar in Tirana“ Restoration and Revitalization Albania Tirana Atelier 4 arTurbina Albania Tirana Atelier 4 “Lalez, individual Villa” Albania Durres AGMA studio Himara Waterfront Albania Himarë Bureau Bas Smets, SON-group “The House of Leaves". National Museum of Secret Surveillance Albania Tirana Studio Terragni Architetti, Elisabetta Terragni, xycomm, Daniele Ledda “Aticco” palace Albania Tirana Studio Raça Arkitektura “Between Olive Trees” Villa Albania Tirana AVatelier Vlora Waterfront Promenade Albania Vlorë Xaveer De Geyter Architects The Courtyard House Albania Shkodra Filippo Taidelli Architetto "Tirana Olympic Park" Albania Tirana DEAstudio BTV Headquarter Vorarlberg and Office Building Austria Dornbirn Rainer Köberl, Atelier Arch. DI Rainer Köberl Austrian Embassy Bangkok Austria Vienna HOLODECK architects MED Campus Graz Austria Graz Riegler Riewe Architekten ZT-Ges.m.b.H. Higher Vocational Schools for Tourism and Catering - Am Wilden Kaiser Austria St. Johann in Tirol wiesflecker architekten zt gmbh Farm Building Josef Weiss Austria Dornbirn Julia Kick Architektin House of Music Innsbruck Austria Innsbruck Erich Strolz, Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architekten Exhibition Hall 09 - 12 Austria Dornbirn Marte.Marte Architekten P2 | Urban Hybrid | City Library Innsbruck Austria Innsbruck -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Beste Leerling Het Letterenhuis Beheert Het Grootste Literaire Archief

Beste leerling Het Letterenhuis beheert het grootste literaire archief van Vlaanderen. Dat archief bevat onder andere brieven, manuscripten, typoscripten, borstbeelden, portretten, foto’s, audio en video en nog veel meer dat te maken heeft met het Vlaamse literaire leven. In ons museum tonen we twee eeuwen Vlaamse literatuur in een permanente tentoonstelling. Met deze brochure willen we je op weg zetten naar het museumbezoek. Na het lezen van de teksten en het bekijken van de foto's, schilderijen, voorwerpen en boeken krijg je een scherper beeld van de verschillende literaire periodes en toonaangevende figuren. Zo zal je hetgeen hier tentoongesteld wordt beter kunnen plaatsen binnen de context van tijd en omgeving. De brochure bevat A-opdrachten, die je vooraf in de les uitvoert, en B-opdrachten, die tijdens het museumbezoek beantwoord kunnen worden. We wensen je veel plezier met de opdrachten en vooral een aangenaam bezoek aan ons museum! 1 Uw tael draagt van uw' aert de onloochenbaerste blyken. A Opdrachten Fragment uit: Jan Frans Willems, Aen de Belgen, 1818. 1 De Nederlandse taal staat centraal in dit fragment. Welke beelden of metaforen gebruikt Jan Frans Willems daarvoor? 2 De eerste versregel verwijst naar de Belgische situatie van die tijd. a) Waarom ligt de nadruk zo sterk op “Ik ook”? b) Hoe is de toestand nu? Ken je vergelijkbare situaties? 3 Bekijk de afbeeldingen op de volgende pagina. a) Welk werk spreekt je aan? Waarom? b) Wat hebben deze covers met elkaar gemeen? 4 Bovenaan deze pagina staat een citaat afkomstig uit hetzelfde gedicht a) Hoe zou je dat kunnen ‘vertalen’? b) Ga je akkoord met deze uitspraak? Waarom (niet)? B Opdrachten 1 Welke term wordt in het museum gebruikt om deze groep ‘taalminnaren’ aan te duiden? Waarom denk je dat die term zo geschikt werd gevonden? 2 Ga op zoek naar een ander heel bekend werk dat werd uitgegeven door Jan Frans Willems. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

Literatuurwetenschap En Uitgeverijonderzoek En Literatuurwetenschap

Cahier voor Literatuurwetenschap 2012 Literatuurwetenschap Cahier voor CLW 4 Literatuurwetenschap Literatuurwetenschap (2012) en uitgeverijonderzoek en uitgeverijonderzoek Cahier voor Literatuurwetenschap Onder impuls van de cultuursociologie en de boekge- schiedenis is de rol van de uitgeverij in de totstandkoming en erkend en bestudeerd. Het staat inmiddels buiten kijf dat het uitgeverijonderzoek heel concreet bewijst dat de liter- 4 (2012) atuurwetenschap geen ‘autonome artefacten’ bestudeert, Dit Cahier voor literatuurwetenschap confronteert de re- CLW sultaten van recent en nog lopend uitgeverijonderzoek met de algemene literatuurwetenschap. De bijdragen demon- streren niet alleen de verscheidenheid die het uitgeverij- Kevin Absillis & Kris Humbeeck (red.) onderzoek vandaag typeert wat aanpak, onderwerpkeuze - worven ideeën en stellen bovenal nieuwe uitdagingen in het vooruitzicht. CLW2011.4.book Page 1 Tuesday, October 30, 2012 3:40 PM Literatuurwetenschap en uitgeverijonderzoek CLW2011.4.book Page 2 Tuesday, October 30, 2012 3:40 PM CLW2011.4.book Page 3 Tuesday, October 30, 2012 3:40 PM CLW 4 • CAHIER VOOR LITERATUURWETENSCHAP LITERATUURWETENSCHAP EN UITGEVERIJONDERZOEK Kevin Absillis & Kris Humbeeck (red.) CLW2011.4.book Page 4 Tuesday, October 30, 2012 3:40 PM © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] De uitgaven van Academia Press worden verdeeld door: J. Story-Scientia nv Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be Ef & Ef Media Postbus 404 3500 AK Utrecht [email protected] www.efenefmedia.nl Kevin Absillis & Kris Humbeeck (red.) Literatuurwetenschap en uitgeverijonderzoek Gent, Academia Press, 2012, 127 pp. -

FEATS Programme 1978

4; ANTWERP SPONSOR FEATS ‘78 FESTIVAL OF EUROPEAN ANGLOPHONE THEATRICAL SOCIETIES ,PROVINCIAAL CENTRUM ARENBERGSCHOUWBURG, ANTWERP MAY 26- 26, 1978 FEATS ‘78 organized in co-operation with the City of Antwerp georganizeerd in samenwerking met de Stad Antwerpen under the patronage of / onder de bescberming tan A. Kinsbergen, Gouverneur van de Provincie Antwerpen Sir David Muirhead, K.C.M.G., C.V.O., Her Britannic Majesty’s Ambassador to Belgium M. Groesser - Schroyens, Burgemeester van de Sled Antwerpen L. Van den Driessche, Rector van de Universitaire Instelling Antwerpen Theo Peters, Her Britannic Majesty’s Consul-General John P. Heimann, Consul-General of the United States of America Dom De Gruyter, Directeur van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Schouwburg, Antwerpen Alfons Goris, Directeur van Studio Herman Teirlinck, Antwerpen Walter Claessens, Directeur van het Reizend Volkstheater, Provincie Antwerpen E. Traey, Directeur Koni nkl ijk Muziekconservatorium Antwerpen R.J. Lhonneux, Voorzitter van de Kamer van Koophandel en Nijverheid, Antwerpen E.L Bridges, Chairman of the British Coordinating Committee Antwerp and wIth special thanks to / en met bljzonder. dank san The British Council, for financial support Phillips Petroleum Company, for donating the FEATS ‘78 cup Schweppes Ltd, for their support Les Fonderies de Cobegge a Andenne, for their assistance FEATS ‘78 organized in co-operation with the City of Antwerp georganizeerd in samenwerking met de Stad Antwerpen under the patronage of / onder de bescberming tan A. Kinsbergen, Gouverneur van de Provincie Antwerpen Sir David Muirhead, K.C.M.G., C.V.O., Her Britannic Majesty’s Ambassador to Belgium M. Groesser - Schroyens, Burgemeester van de Sled Antwerpen L. -

Brussels, the Avant-Garde, and Internationalism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography <new page>Chapter 15 Met opmaak ‘Streetscape of New Districts Permeated by the Fresh Scent of Cement’:. Brussels, the Avant-Garde, and Internationalism1 La Jeune Belgique (1881–97);, L’Art Moderne (1881–1914);, La Société Nouvelle (1884–97);, Van Nu en Straks (1893–94; 1896– 1901); L’Art Libre (1919–22);, Signaux (1921, early title of Le Disque Vert, 1922–54);, 7 Arts (1922–8);, and Variétés (1928– 30). Francis Mus and Hans Vandevoorde In 1871 Victor Hugo was forced to leave Brussels because he had supported the Communards who had fled there.2 This date could also be seen as symbolisiizing the 1 This chapter has been translated from the Dutch by d’onderkast vof. 2 Marc Quaghebeur, ‘Un pôle littéraire de référence internationale’, in Robert Hoozee (ed.), Bruxelles. Carrefour de cultures (Antwerp: Fonds Mercator, 2000), 95–108. For a brief 553 passing of the baton from the Romantic tradition to modernism, which slowly emerged in the 1870s and went on to reach two high points: Art Nouveau at the end of the nineteenth century and the so-called historical avant-garde movements shortly after World War I. The significance of Brussels as the capital of Art Nouveau is widely acknowledged.3 Its renown stems primarily from its architectural achievements and the exhibitions of the artist collective ‘Les XX’ (1884–93),4 which included James Ensor, Henry Van de Velde, Théo van Rysselberghe, George Minne, and Fernand Khnopff. -

Bernheim, Nele. "Fashion in Belgium During the First World War and the Case of Norine Couture." Fashion, Society, and the First World War: International Perspectives

Bernheim, Nele. "Fashion in Belgium during the First World War and the case of Norine Couture." Fashion, Society, and the First World War: International Perspectives. Ed. Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin and Sophie Kurkdjian. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021. 72–88. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350119895.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 18:11 UTC. Copyright © Selection, editorial matter, Introduction Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards- Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian and Individual chapters their Authors 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Fashion in Belgium during the First World War and the case of Norine Couture N e l e B e r n h e i m What happens to civil life during wartime is a favorite subject of historians and commands major interest among the learned public. Our best source on the situation in Belgium during the First World War is Sophie De Schaepdrijver’s acclaimed book De Groote Oorlog: Het Koninkrijk Belgi ë tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Th e Great War: Th e Kingdom of Belgium During the Great War). 1 However, to date, there has been no research on the Belgian wartime luxury trade, let alone fashion. For most Belgian historians, fashion during this time of hardship was the last of people’s preoccupations. Of course, fashion historians know better.2 Th e contrast between perception and reality rests on the clich é that survival and subsistence become the overriding concerns during war and that aesthetic life freezes—particularly the most “frivolous” of all aesthetic endeavors, fashion. -

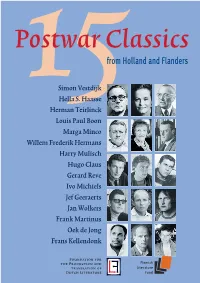

From Holland and Flanders

Postwar Classics from Holland and Flanders Simon Vestdijk 15Hella S. Haasse Herman Teirlinck Louis Paul Boon Marga Minco Willem Frederik Hermans Harry Mulisch Hugo Claus Gerard Reve Ivo Michiels Jef Geeraerts Jan Wolkers Frank Martinus Oek de Jong Frans Kellendonk Foundation for the Production and Translation of Dutch Literature 2 Tragedy of errors Simon Vestdijk Ivory Watchmen n Ivory Watchmen Simon Vestdijk chronicles the down- I2fall of a gifted secondary school student called Philip Corvage. The boy6–6who lives with an uncle who bullies and humiliates him6–6is popular among his teachers and fellow photo Collection Letterkundig Museum students, writes poems which show true promise, and delights in delivering fantastic monologues sprinkled with Simon Vestdijk (1898-1971) is regarded as one of the greatest Latin quotations. Dutch writers of the twentieth century. He attended But this ill-starred prodigy has a defect: the inside of his medical school but in 1932 he gave up medicine in favour of mouth is a disaster area, consisting of stumps of teeth and literature, going on to produce no fewer than 52 novels, as the jagged remains of molars, separated by gaps. In the end, well as poetry, essays on music and literature, and several this leads to the boy’s downfall, which is recounted almost works on philosophy. He is remembered mainly for his casually. It starts with a new teacher’s reference to a ‘mouth psychological, autobiographical and historical novels, a full of tombstones’ and ends with his drowning when the number of which6–6Terug tot Ina Damman (‘Back to Ina jealous husband of his uncle’s housekeeper pushes him into Damman’, 1934), De koperen tuin (The Garden where the a canal. -

SCHRIJVERS DIE NOG MAAR NAMEN LIJKEN Het Onvoorstelbare Thema Van Herman Teirlinck

SCHRIJVERS DIE NOG MAAR NAMEN LIJKEN Het onvoorstelbare thema van Herman Teirlinck In de reeks Schrijvers die nog maar namen lijken buigen jonge auteurs, literatuurcritici en -wetenschappers zich over twintigste-eeuwse schrijvers van wie de naam wel breed bekend is, maar van wie men zich kan afvragen of ze nog wel worden gelezen. Bart Van der Straeten vertelt hoe hij Herman Teirlinck op het spoor kwam en leest een oeuvre dat op verschillende manieren één groot onderliggend thema lijkt uit te beelden. Het is de verhulling van de waarheid die ons met elkaar verbindt en die wij in elkaar herkennen. Een foto van Herman Teirlinck in brasserie De Drie Fonteinen in Beersel _ BART VAN DER STRAETEN Herman Teirlinck was een naam die wel eens opdook, nu en dan, in verschillende con- texten, maar waar ik nooit een helder beeld van kreeg. Op televisie hoorde ik in mijn jeugd verhalen over de Studio Herman Teirlinck, de roemruchte acteursopleiding in Antwerpen die zowat elk Vlaams acteertalent had gevormd. De Studio was door Teir- linck zelf opgericht in 1946 en bleef bestaan tot ongeveer 2000; Teirlinck had er zelf lesgegeven, onder meer aan de latere directrice van de studio Dora van der Groen. De documentaire Herman Teirlinck van de filmmaker Henri Storck uit 1953 toont beelden van Teirlinck als een autoritair en bevlogen lesgever, die met onder anderen acteur-in- opleiding Senne Rouffaer van gedachten wisselt over de interpretatie van het Middelne- derlandse toneelstuk Elckerlijc. Teirlincks opvattingen over theater zijn in 1959 gebun- deld in Dramatisch peripatetikon, eind 2017 opnieuw uitgegeven door ASP Editions. -

Anet Library Automation

Anet Library Automation Anke Jacobs 24 juni 2016 Anet, a library network Academic and special libraries in Antwerp/ Limburg provinces °medio‘80 former UAntwerpen former City Library of Antwerp former UHasselt Idea of collective library automation . Cost . Catalogue and cataloguing rules Anet role . ICT support . Delivery of software (as of 2000 Brocade) 1 Anet, a library network Current partners Universities City of Antwerp . UAntwerpen . Erfgoedbibliotheek Hendrik Conscience (heritage library) . UHasselt . Museum Plantin Moretus Schools for Higher Education . Antwerp City Archives . Letterenhuis (archive and Museum) . Artesis Plantijn Hogeschool Antwerpen . Middelheim Museum . Karel de Grote Hogeschool . Rubenianum . MAS . … Others . Royal Museum of Fine Arts Research, Education, Heritage, Documentation, . Antwerp Port Authority Information and Leisure . Mechelen City Archives . Tongerlo Abbey Students, Professors, Researchers, Staff, . … General Public Anet, a library network ‐ Data Union catalogue (2.300.000 records) Number of objects Number of records 2 Anet, a team Team leader: Technologic manager: Jan Corthouts Richard Philips Software developers (3) Coordinator IR (1+1) System engineer (1) Coordinator Metadata (1+1) Project managers (2) Anet, a team Finances Allowance from UAntwerpen (30%) External revenue (70%) . Contracts . Projects 3 Brocade, the library system Brocade as library system . Fully web based system https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brocade_Library_Services . In‐house development (1998‐ ) . In use since 2000 . Current release: 4.10 . 1 to 2 releases per year Automatic synchronization New releases: automatically installed on all installations Bug fixes: pushed automatically on all installations the next day Cooperation CIPAL . Commercial partner . ICT services to municipalities and provinces . Cooperation since 2001 . Distribution and implementation of Brocade . Active in the market of public libraries . -

Flemish Community)

Youth Wiki national description Youth policies in Belgium (Flemish Community) 2019 The Youth Wiki is Europe's online encyclopaedia in the area of national youth policies. The platform is a comprehensive database of national structures, policies and actions supporting young people. For the updated version of this national description, please visit https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/en/youthwiki 1 Youth 2 Youth policies in Belgium (Flemish Community) – 2019 Youth Wiki Belgium (Flemish Community) ........................................................................... 6 1. Youth Policy Governance................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Target population of youth policy ............................................................................................. 8 1.2 National youth law .................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 National youth strategy ........................................................................................................... 10 1.4 Youth policy decision-making .................................................................................................. 14 1.5 Cross-sectoral approach with other ministries ....................................................................... 18 1.6 Evidence-based youth policy ................................................................................................... 18 1.7 Funding youth policy