Rodriguez, Luz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Children of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre. Tony Earnest Medlin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Medlin, Tony Earnest, "The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7281. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7281 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

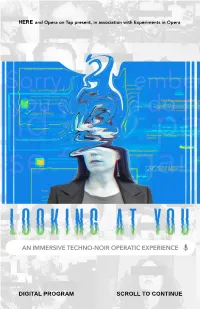

DIGITAL PROGRAM SCROLL to CONTINUE Click on Any Section Below to Jump to the Page

and Opera on Tap present, in association with Experiments in Opera DIGITAL PROGRAM SCROLL TO CONTINUE Click on any section below to jump to the page. SHOW INFO 3 BIOS 4 RESOURCES 15 DIGITAL PRIVACY KIT 15 PRODUCTION HISTORY 16 ABOUT HERE 18 MEMBERSHIP 20 HERE STAFF 21 FUNDING 22 SURVEY 25 HEREART 26 FOLLOW US 26 and Opera on Tap present, in association with Experiments in Opera Story by Rob Handel, Kristin Marting, and Kamala Sankaram Composed by Kamala Sankaram Libretto by Rob Handel Developed with, Co-Choreographed and Directed by Kristin Marting Music Direction by Samuel McCoy Performers Paul An, Adrienne Danrich, Blythe Gaissert, Eric McKeever, Mikki Sodergren, Brandon Snook, and Jorell Williams* Video Designer David Bengali Technologists Alessandro Acquisti, Ralph Gross Tablet Technologists Joe Holt, Daniel Dickison Scenic Designer Nic Benacerraf Costume Designer Kate Fry Lighting Designer Ayumu “Poe” Saegusa Choreographer Amanda Szeglowski Sound Engineer Nathaniel Butler Production Stage Manager Westie Productions Piano Mila Henry Saxophones Jeff Hudgins, Ed RosenBerg, Josh Sinton, and Matt Blanchard** Production Manager Michaelangelo De Serio Technical Director Eli Reid Assistant Costume Designer Tekla Monson Associate Video Designer Shefali Nayak Projection Animation Assistant Kathleen Fox Assistant Directors Anne Bakan, Sim Yan Ying Assistant Stage Manager/Wardrobe Manager Aoife Hough Stitcher Elise Walsh * 9/15–21 performances only ** 9/21 performances only Looking at You is made possible through the generous support of Carnegie Mellon University; Dashlane; KSF; Mental Insight Foundation; New England Foundation for the Arts; Puffin Foundation; Opera America’s Grants for Female Composers supported by the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation and Opera America’s Innovation Fund supported by the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation; and the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. -

Steve Paxton and Lisa Nelson, Night Stand, 2004.Pdf

Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton Night Stand, 2004 Dia:Chelsea 541 West 22nd Street New York City 212 989 5566 www.diaart.org Dia Art Foundation presents Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton Night Stand, 2004 Thursday, October 10–Saturday, October 12, 2013, 8 pm Thursday, October 17–Saturday, October 19, 2013, 8 pm Dance, setting, and sound compilation by Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton Lighting by Carol Mullins performers Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton production manager Adam Macks music Excerpts from Automatic Writing (1979), eL/Aficionado (1994), and Dust (2000) by Robert Ashley (Lovely Music) and Zvuki Mu (1989) by Pyotr Mamonov (Opal Records). Dia’s presentation of Night Stand marks the United States premiere. Night Stand has been previously performed at Centre chorégraphique national de Montpellier Languedoc–Roussillon, France; Marseille Objectif Danse, France; Side Step Festival, Helsinki, Finland; SESC Belenzinho, São Paulo, Brazil; L’animal a l’esquena, Celrà, Spain; and Spiral Hall, Tokyo, Japan. This program is made possible in part by Dia’s Commissioning Committee: Jill and Peter Kraus, Leslie and Mac McQuown, Genny and Selmo Nissenbaum, and Liz Gerring Radke and Kirk August Radke. Front Cover: Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton, Night Stand, 2004. Performance at L’animal a l’esquena, Celrà, Spain, 2008. Photo © Jordi Bover. Progress Report: Night Stand Night Stand is the third collaboration between Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton, Paxton and Nelson’s performing partnership dates back to 1975. Paxton’s after PA RT, which they performed from 1978 to 2002, and Population, which approach to physical improvisation is sourced in an ongoing investigation of the was performed once in 1988. -

The Long Christmas Dinner Leon Botstein, Conductor

12-19 ASO_GP 12/2/14 11:22 AM Page 1 Friday Evening, December 19, 2014, at 8:00 in association with the Bard Center presents The Long Christmas Dinner Leon Botstein, Conductor The Long Christmas Dinner One-act play by Thornton Wilder Intermission The Long Christmas Dinner One-act opera by Paul Hindemith Libretto by Thornton Wilder Director: Jonathan Rosenberg Scenic Designer: Zane Pihlstrom Costume Designer: Olivera Gajic Lighting Designer: Peter West Producer: Thurmond Smithgall The play The Long Christmas Dinner is presented by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. The opera The Long Christmas Dinner is presented by arrangement with European American Music Distribution Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, publisher and copyright owner. Video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. This evening’s event will run approximately two hours including one 20-minute intermission. This project is made possible with the support of The Lanie & Ethel Foundation and The Wilder Family. Alice Tully Hall Please make certain your cellular phone, pager, or watch alarm is switched off. 12-19 ASO_GP 12/2/14 11:22 AM Page 2 Lincoln Center Leon Botstein Lars Berge Arielle Goldman Ryan-James Libby Matthews Hatanaka Hannah Mitchell Claire Moodey Michael Salinas Glenn Seven Allen Kathryn Guthrie Catherine Martin Scott Murphree Sara Murphy Jarrett Ott Josh Quinn Camille Zamora Leon Botstein photo by Ric Kallaher; Arielle Goldman, Ryan-James Hatanaka, and Libby Matthews photos by Deborah Lopez; Hannah Mitchell photo by Michael Medeiros; Claire Moodey photo by Commontiger Photography; Michael Salinas photo by Evan Smith; Kathryn Guthrie photo by Claire McAdams; Catherine Martin photo by Kristen Hoebermann; Jarrett Ott photo by Steve Riskind; Josh Quinn photo by Kate Lemmon Photography; Camille Zamora photo by Liron Amsellem. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

1984 Category Artist(S)

1984 Category Artist(s) Artist/Title Of Work Venue Choreographer/Creator Anne Bogart South Pacific NYU Experimental Theatear Wing Eiko & Koma Grain/Night Tide DTW Fred Holland/Ishmael Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders The Kitchen Houston Jones Julia Heyward No Local Stops Ohio Space Mark Morris Season DTW Nina Wiener Wind Devil BAM Stephanie Skura It's Either Now or Later/Art Business DTW, P.S. 122 Timothy Buckley Barn Fever The Kitchen Yoshiko Chuma and the Collective Work School of Hard Knocks Composer Anthony Davis Molissa Fenley/Hempshires BAM Lenny Pickett Stephen Pertronio/Adrift (With Clifford Danspace Project Arnell) Film & TV/Choreographer Frank Moore & Jim Self Beehive Nancy Mason Hauser & Dance Television Workshop at WGBH- Susan Dowling TV Lighting Designer Beverly Emmons Sustained Achievement Carol Mulins Body of Work Danspace Project Jennifer Tipton Sustained Achievement Performer Chuck Greene Sweet Saturday Night (Special Citation) BAM John McLaughlin Douglas Dunn/ Diane Frank/ Deborah Riley Pina Bausch and the 1980 (Special Citation) BAM Wuppertaler Tanztheatre Rob Besserer Lar Lubovitch and Others Sara Rudner Twyla Tharp Steven Humphrey Garth Fagan Valda Setterfield David Gordon Special Achievement/Citations Studies Project of Movement Research, Inc./ Mary Overlie, Wendell Beavers, Renee Rockoff David Gordon Framework/ The Photographer/ DTW, BAM Sustained Achievement Trisha Brown Set and Reset/ Sustained Achievement BAM Visual Designer Judy Pfaff Nina Wiener/Wind Devil Power Boothe Charles Moulton/ Variety Show; David DTW, The Joyce Gordon/ Framework 1985 Category Artist(s) Artist/Title of Work Venue Choreographer/Creator Cydney Wilkes 16 Falls in Color & Searching for Girl DTW, Ethnic Folk Arts Center Johanna Boyce Johanna Boyce with the Calf Women & DTW Horse Men John Jesurun Chang in a Void Moon Pyramid Club Bottom Line Judith Ren-Lay The Grandfather Tapes Franklin Furnace Susan Marshall Concert DTW Susan Rethorst Son of Famous Men P. -

Mabou Minesâ•Ž Dead End Kids and Performing Artists for Nuclear

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2020 Mabou Mines’ Dead End Kids and Performing Artists for Nuclear Disarmament Hillary Miller Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/451 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Side by Side: Collaborative Artistic Practices in 1. THOMAS J. LAX 2. GWYNETH SHANKS 3. ROSS ELFLINE 4. ALLIE TEPPER 5. WENDY PERRON the United States, 1960s–1980s Preface Introduction: Being With, Thoughts on the Common Ground: Haus-Rucker-Co’s Food Individual Collective: A Conversation with How Grand Union Found a Home Outside of Collective City I and Collaborative Design Practice Senga Nengudi SoHo at the Walker LIVING COLLECTIONS CATALOGUE VOLUME III. SIDE BY SIDE Mabou Mines’ Dead End Kids & Performing Artists for Nuclear Disarmament By Hillary Miller Mabou Mines performers in Dead End Kids: A History of Nuclear Power presented by the Walker Art Center at the University of Minnesota’s Coffman Union Great Hall, Minneapolis, March 1982. Walker Art Center Archives. ABSTRACT CITATION Performance studies scholar and theater historian Hillary Miller offers a new study of the 1980 production of Dead End Kids: A History of Nuclear Power by the New York-based avant-garde theater collective, Mabou Mines. Through a close reading of the play, Miller explores the relationship between this production and the little researched organization, Performing Artists for Nuclear Disarmament (PAND), revealing the correlations between collaboratively-generated theater practices and concurrent protest movements. -

18-19 REP SEASON | WINTER 6O

18-19 REP SEASON | WINTER 6o The Music Man The Crucible A Doll’s House, Part 2 Sweat Noises Off The Cake Sweeney Todd Around the World in 80 Days asolorep asolorep PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MICHAEL DONALD EDWARDS MANAGING DIRECTOR LINDA DiGABRIELE PROUDLY PRESENTS BY Arthur Miller DIRECTED BY Michael Donald Edwards Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design & Original Composition LEE SAVAGE TRACY DORMAN JEN SCHRIEVER FABIAN OBISPO Hair/Wig & Make-up Design New York Casting Chicago Casting Local Casting Voice & Dialect Coach MICHELLE HART STEWART/WHITLEY CASTING SIMON CASTING CELINE ROSENTHAL PATRICIA DELOREY Fight Director Production Stage Manager Stage Manager & Fight Captain Assistant Stage Manager Dramaturg ROWAN JOHNSON NIA SCIARRETTA* DEVON MUKO* JACQUELINE SINGLETON* PAUL ADOLPHSEN Directing Fellow Music Coach Stage Management Apprentice Stage Management Apprentice Dramaturgy & Casting Apprentice TOBY VERA BERCOVICI LIZZIE HAGSTEDT CAMERON FOLTZ CHRISTOPHER NEWTON KAMILAH BUSH The Crucible is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York Directors are members of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society; Designers are members of the United Scenic Artists Local USA-829; Backstage and Scene Shop Crew are members of IATSE Local 412. The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. CO-PRODUCERS Gerri Aaron • Nancy Blackburn • Tom and Ann Charters • Annie Esformes, in loving memory of Nate Esformes • Shelley and Sy Goldblatt Nona -

By Tony Taccone and Bennett S

BY TONY TACCONE AND BENNETT S. COHEN, ADAPTED FROM THE NOVEL BY SINCLAIR LEWIS SOUND DESIGN AND MUSIC BY PAUL JAMES PRENDERGAST DIRECTED BY LISA PETERSON DEAR FRIENDS, Four years ago, in the lead-up to the 2016 election, Berkeley Rep produced Tony Taccone and Bennett Cohen’s adaptation of Sinclair Lewis’ frighteningly prescient novel. With a desire to see the story reach the widest possible audience, and celebrating the impulse that led the wpa in 1936 to share the original stage version of Lewis’ novel for free with 21 theatres across the country, Berkeley Rep offered the rights to Tony and Bennett’s adaptation to theatres, community centers, universities — anyone who wanted to put together their own production or reading. And now, in 2020, this story feels all the more vital, and the need to share it widely even more compelling. I am honored that more than 75 organizations from more than 20 states have partnered with us to share this production of It Can’t Happen Here for free with their audiences and communities. We are joined in this effort by long-time theatre colleagues, by universities from Howard in Wash- ington, DC to Saint Cloud State in Minnesota (near Lewis’ hometown), by libraries, community centers, and radio stations. I am deeply grateful to Tony and Bennett, director Lisa Peterson, sound designer Paul James Prendergast and his small but mighty team, and this extraordinary cast who have collaborated across miles and time zones, through wildfires and new technology, for their conviction that the- atre matters, that narrative helps us to see the world more clearly, and that together we have the capacity to effect change. -

Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Between Music

Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress 7 Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Of Essence and Context Between Music and Philosophy Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress Volume 7 Series Editor Dario Martinelli, Faculty of Creative Industries, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilnius, Lithuania [email protected] The series originates from the need to create a more proactive platform in the form of monographs and edited volumes in thematic collections, to discuss the current crisis of the humanities and its possible solutions, in a spirit that should be both critical and self-critical. “Numanities” (New Humanities) aim to unify the various approaches and potentials of the humanities in the context, dynamics and problems of current societies, and in the attempt to overcome the crisis. The series is intended to target an academic audience interested in the following areas: – Traditional fields of humanities whose research paths are focused on issues of current concern; – New fields of humanities emerged to meet the demands of societal changes; – Multi/Inter/Cross/Transdisciplinary dialogues between humanities and social and/or natural sciences; – Humanities “in disguise”, that is, those fields (currently belonging to other spheres), that remain rooted in a humanistic vision of the world; – Forms of investigations and reflections, in which the humanities monitor and critically assess their scientific status and social condition; – Forms of research animated by creative and innovative humanities-based -

Full Cast & Credits

DANSPACEPROJECT40 YOU MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. Help us celebrate 40 years of Danspace Project! Donate at danspaceproject.org/supportjoin ABOUT DANSPACE PROJECT Founded in 1974, Danspace Project presents new work in dance, supports a diverse range of choreographers in developing their work, encourages experimentation, and connects artists to audiences. Now in its fourth decade, Danspace Project has supported a vital community of contemporary dance artists in an environment unlike any other in the United States. Located in the historic St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, Danspace shares its facility with the Church, The Poetry Project, and New York Theatre Ballet. Danspace Project’s Commissioning Initiative has commissioned over 450 new works since its inception in 1994. Danspace Project’s Choreographic Center Without Walls (CW²) provides context for audiences and increased support for artists. Our presentation programs (including Platforms, Food for Thought, DraftWork), Commissioning Initiative, residencies, guest artist curators, and contextualizing activities and materials are core components of CW² offering a responsive framework for artists’ works. Since 2010, we have produced eight Platforms, published eight print catalogues and five e-books, launched the Conversations Without Walls discussion series, and explored models for public discourse and residencies. FOLLOW US! Facebook: Danspace Project Instagram: DanspaceProject Twitter: @DanspaceProject Tumblr:danspaceproject.tumblr.com www.danspaceproject.org BE FIRST. Join us in celebrating 40