The Use of Personal Anecdotes in the Ontario Legislative Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Volunteer of the Year Award Winner, Richard Sarrazin

JANUARY 2009 • THE PUBLICATION OF THE MÉTIS NATION OF ONTARIO SINCE 1997 MÉTISVOYAGEUR The VOLUNTEER CAMAs OF THE ABORIGINAL YEAR AWARD MUSIC AWARDS KEEPING TRADITION ALIVE SUDBURY’S RICHARD SALUTE OUR BEST OLIVINE BOUSQUET DANCERS TAKE THE SARRAZIN HONOURED PAGE 29 MÉTIS JIG ON THE ROAD • PAGE 16 PAGE 15 NEW LEADERSHIP, NEW ENERGY, NEW DIRECTION: AN HISTORIC DAY front row, left to right: MNO President Gary Lipinski; Ontario Minister of Aboriginal Affairs, the Honourable Brad Duguid and PCMNO Chair France Picotte. back row, left to right: Métis youth Janine Landry, Senator Elmer Ross and Senator Brenda Powley. On November 18th an historic agreement was signed recognizing the unique history and ways of life of Métis communities in Ontario. This framework agreement sets the course for a new, collaborative relationship between the Ontario Government and the Métis Nation of Ontario. More about the signing and the Special Presidents’ Assembly/AGA on pages 3 to 10. A CANOE CHAIR OF LOUIS HEROES WITH NO MÉTIS RIEL DAY COME IN PADDLES STUDIES MÉTIS ACROSS PROVINCE ALL SIZES UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA GATHER TO HONOUR SEVEN YEAR-OLD MÉTIS GRAND RIVER MÉTIS SELECTED TO HOST THE MEMORY OF A DOES HER PART IN FIGHT LOOKING FOR PADDLES CHAIR OF MÉTIS STUDIES GREAT MÉTIS HERO AGAINST CANCER PAGE 25 40025265 PAGE 13 PAGES 18 + 19 PAGE 26 2 MÉTIS VOYAGEUR ∞ January 2009 Métis Community Councils FONDLY REMEMBERED: NEW ARRIVAL LETTERS: THE MÉTIS Praise for a VOYAGEUR Métis Voyageur WINTER 2009, NO.56 contributor editor Hi. I just had to tell you, the arti- Linda Lord cle by Sabrina Stoessinger (See Métis Voyageur, Autumn 2008, design & production page 19, “Practice Makes Perfect”) Marc St.Germain has really moved me, and each time I look a kid-in-care in the contributors face, I now look for more. -

Table of Contents/Table De Matières

Comptes publics de l’ Public Accounts of Ministry Ministère of des Finance Finances PUBLIC COMPTES ONTARIOONTARIO ACCOUNTS PUBLICS of de ONTARIO L’ONTARIO This publication is available in English and French. CD-ROM copies in either language may be obtained from: ServiceOntario Publications Telephone: (416) 326-5300 Toll-free: 1-800-668-9938 2011–2012 TTY Toll-free: 1-800-268-7095 Website: www.serviceontario.ca/publications For electronic access, visit the Ministry of Finance website at www.fin.gov.on.ca Le présent document est publié en français et en anglais. 2011-2012 On peut en obtenir une version sur CD-ROM dans l’une ou l’autre langue auprès de : D E TA I L E D S C H E D U L E S Publications ServiceOntario Téléphone : 416 326-5300 Sans frais : 1 800 668-9938 O F P AY M E N T S Téléimprimeur (ATS) sans frais : 1 800 268-7095 Site Web : www.serviceontario.ca/publications Pour en obtenir une version électronique, il suffit de consulter le site Web du ministère des Finances à www.fin.gov.on.ca D ÉTAILS DES PAIEMENTS © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2012 © Imprimeur de la Reine pour l’Ontario, 2012 ISSN 0381-2375 (Print) / ISSN 0833-1189 (Imprimé) ISSN 1913-5556 (Online) / ISSN 1913-5564 (En ligne) Volume 3 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DE MATIÈRES Page General/Généralités Guide to Public Accounts.................................................................................................................................. 3 Guide d’interprétation des comptes publics ...................................................................................................... 5 MINISTRY STATEMENTS/ÉTATS DES MINISTÈRES Aboriginal Affairs/Affaires autochtones ........................................................................................................... 7 Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs/Agriculture, Alimentation et Affaires rurales......................................... -

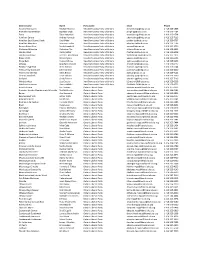

District Name

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson -

Hon. David Orazietti Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services 16 Floor, George Drew Building 25 Grosvenor Street T

Hon. David Orazietti Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services 16th Floor, George Drew Building 25 Grosvenor Street Toronto, ON M7A 1Y6 July 25, 2016 RE: End the Incarceration of Immigration Detainees in Provincial Prisons Dear David, First, let me extend on behalf of Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario (RNAO), a warm welcome and congratulations on your recent appointment as the Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services. We at RNAO look very much forward to working with you to build healthier communities in our province. To this end, we are asking to meet with you to discuss perspectives and collaboration. As the professional association representing registered nurses (RN), nurse practitioners (NP) and nursing students in Ontario, RNAO is a strong and consistent advocate for the need to improve health, health care, and human rights protection within our provincial correctional facilities.1 2 We have long been concerned with the criminalization of people with mental health and addiction challenges.3 Therefore, we urge you to end the ongoing incarceration of immigration detainees in provincial prisons, and prevent more needless deaths of immigration detainees in your care. The Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) routinely transfers immigration detainees – refugee claimants, survivors of trauma, and other vulnerable non-citizens, including many with mental health challenges – to medium-maximum security provincial correctional facilities.4 Having a severe physical or mental illness or expressing thoughts -

PROVINCIAL POLITICS: SUMMARY of POSITIVE Now I'd Like to Read You the Names of Some of the Cabinet Ministers in the Mike Harris Government

Impressions of the Senior Ontario Cabinet Ministers PROVINCIAL POLITICS: SUMMARY OF POSITIVE Now I'd like to read you the names of some of the cabinet ministers in the Mike Harris government. For each one, please tell me whether you have an overall positive or negative impression of that person. If you do not recognize the name, just say so. How about ... REGION REGION TYPE AREA CODE Total Ham/Nia South Eastern Northern Ont (ex. GTA Urban Rural 416 905 g West GTA) Base: All respondents Unweighted Base 1001 175 175 151 100 601 400 871 130 218 178 Weighted Base 1001 87 252 200 82 621 380 857 144 210 166 Flaherty 215 19 46 48 13 126 88 185 30 47 40 21% 22% 18% 24% 16% 20% 23% 22% 21% 23% 24% Tony Clement 233 25 46 53 10 134 99 198 34 52 45 23% 29% 18% 27% 12% 22% 26% 23% 24% 25% 27% Elizabeth Witmer 234 19 77 43 20 159 75 198 35 48 27 23% 21% 31% 21% 24% 26% 20% 23% 25% 23% 16% Janet Ecker 263 21 62 60 16 160 103 232 31 57 45 26% 24% 25% 30% 20% 26% 27% 27% 21% 27% 27% Chris Hodgson 1127 242318724097152119 11% 7% 10% 11% 22% 12% 11% 11% 10% 10% 12% Chris Stockwell 228 16 42 39 11 109 119 195 34 69 48 23% 19% 17% 20% 14% 18% 31% 23% 23% 33% 29% Impressions of the Senior Ontario Cabinet Ministers PROVINCIAL POLITICS:. SUMMARY OF NEGATIVE Now I'd like to read you the names of some of the cabinet ministers in the Mike Harris government. -

50 Priority Ridings Which Will Determine the Outcome of This Election

50 Priority Ridings Which Will Determine The Outcome of This Election CAW PREFERRED LAST ELECTION RESULTS: PROV RIDING CANDIDATE PARTY CON LIB NDP GRN % % % % BC Esquimalt – Juan de Fuca Lillian Szpak LIB 34 34 23 8 BC Kamloops – Thompson – Cariboo Michael Crawford NDP 46 10 36 8 BC Nanaimo-Alberni Zeni Maartman NDP 47 9 32 12 BC North Vancouver Taleeb Noormohamed LIB 42 37 9 11 BC Saanich – Gulf Islands Elizabeth May GRN 43 39 6 10 BC Surrey North Jasbir Sandhu NDP 39 15 36 6 BC Vancouver Island North Ronna-Rae Leonard NDP 46 4 41 8 BC Vancouver South Ujjal Dosanjh LIB 38 38 18 5 BC Vancouver Quadra Joyce Murray LIB 37 46 8 9 SK Palliser Noah Evanchuck NDP 44 17 34 5 SK Saskatoon – Rosetown – Biggar Nettie Wiebe NDP 45 4 44 5 MB Winnipeg North Rebecca Blaikie NDP 10 46 41 1 MB Winnipeg South Centre Anita Neville LIB 36 42 14 7 ON Ajax – Pickering Mark Holland LIB 38 45 9 7 ON Bramalea – Gore – Malton Gurbax Malhi LIB 37 45 12 5 ON Brampton – Springdale Ruby Dhalla LIB 39 41 12 8 ON Brampton West Andrew Kania LIB 40 40 14 6 ON Brant Lloyd St. Amand LIB 42 33 17 7 ON Davenport Andrew Cash NDP 11 46 31 10 ON Don Valley West Rob Oliphant LIB 39 44 10 6 ON Eglinton – Lawrence Joe Volpe LIB 39 44 8 8 ON Essex Taras Natyshak NDP 40 29 27 4 ON Guelph Frank Valeriote LIB 29 32 16 21 ON Haldimand-Norfolk Bob Speller LIB 41 32 12 4 ON Kenora Roger Valley LIB 40 32 23 5 ON Kingston and Islands Ted Hsu LIB 33 39 17 11 ON Kitchener – Waterloo Andrew Telegdi LIB 36 36 15 12 ON Kitchener Centre Karen Redman LIB 37 36 18 9 ON London North Centre Glen -

Tue 3 Oct 2000 / Mar 3 Oct 2000

No. 83A No 83A ISSN 1180-2987 Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative of Ontario de l’Ontario First Session, 37th Parliament Première session, 37e législature Official Report Journal of Debates des débats (Hansard) (Hansard) Tuesday 3 October 2000 Mardi 3 octobre 2000 Speaker Président Honourable Gary Carr L’honorable Gary Carr Clerk Greffier Claude L. DesRosiers Claude L. DesRosiers Hansard on the Internet Le Journal des débats sur Internet Hansard and other documents of the Legislative Assembly L’adresse pour faire paraître sur votre ordinateur personnel can be on your personal computer within hours after each le Journal et d’autres documents de l’Assemblée législative sitting. The address is: en quelques heures seulement après la séance est : http://www.ontla.on.ca/ Index inquiries Renseignements sur l’index Reference to a cumulative index of previous issues may be Adressez vos questions portant sur des numéros précédents obtained by calling the Hansard Reporting Service indexing du Journal des débats au personnel de l’index, qui vous staff at 416-325-7410 or 325-3708. fourniront des références aux pages dans l’index cumulatif, en composant le 416-325-7410 ou le 325-3708. Copies of Hansard Exemplaires du Journal Information regarding purchase of copies of Hansard may Pour des exemplaires, veuillez prendre contact avec be obtained from Publications Ontario, Management Board Publications Ontario, Secrétariat du Conseil de gestion, Secretariat, 50 Grosvenor Street, Toronto, Ontario, M7A 50 rue Grosvenor, Toronto (Ontario) M7A 1N8. Par 1N8. Phone 416-326-5310, 326-5311 or toll-free téléphone : 416-326-5310, 326-5311, ou sans frais : 1-800-668-9938. -

PDF of Dixie: Orchards to Industry by Kathleen A. Hicks

Dixie: Orchards to Industry Kathleen A. Hicks DIXIE: ORCHARDS TO INDUSTRY is published by The Friends of the Mississauga Library System 301 Burnhamthorpe Road West, Mississauga, Ontario L5B 3Y3 Canada Copyright © 2006 Mississauga Library System Dixie: Orchards to Industry All rights reserved. II ISBN 0-9697873-8-3 Written by Kathleen A. Hicks Edited by Michael Nix Graphic layout by Joe and Joyce Melito Cover design by Stephen Wahl Front cover photos - The Region of Peel Archives Back cover photo by Stephen Wahl No part of this publication may be produced in any form without the written permission of the Mississauga Library System. Brief passages may be quoted for books, newspaper or magazine articles, crediting the author and title. For photographs contact the source. Extreme care has been taken where copyright of pictures is concerned and if any errors have occurred, the author extends her utmost apology. Care has also been taken with research material. If anyone encounters any discrepancy with the facts contained herein, please send Upper Canada Map (Frederick R. Bercham) your written information to the author in care of the Mississauga Library System. Dixie: Orchards to Industry (Kathleen A. Hicks) (Kathleen Other Books by Kathleen Hicks III The Silverthorns: Ten Generations in America Kathleen Hicks’ V.I.P.s of Mississauga The Life & Times of the Silverthorns of Cherry Hill Clarkson and Its Many Corners Meadowvale: Mills to Millennium Lakeview: A Journey From Yesterday Cooksville: Country to City VIDEO Riverwood: The Estate Dreams Are Made Of Dedication IV dedicate this book to all the people I know and have known who have hailed from Dixie, whom I have shared many inter- esting stories with over the years and have admired tremen- dously for their community dedication: William Teggart, the Kennedys, Dave and Laurie Pallett, Jim McCarthy, Colonel IHarland Sanders, Gord Stanfield, Mildred and Jack Bellegham and Dave Cook to mention a few. -

(& Windows) Opens Doors

A Magazine for Alumni and Friends of Mohawk College Mohawk Diploma Fall 2004 OPENSOPENS DOORSDOORS (&(& WINDOWS)WINDOWS) Peter Rakoczy, Mohawk Alumnus and GM of Worldwide Microsoft Consulting Services Strategy shares some ‘Words of Wisdom’ Publications Mail Agreement 40065780 ALSO INSIDE: Movin’ On Up ~ Turn Up the Heat ~ Life of the Party FEATURES O N T H E COVER 24 WORDS TO LIVE BY Peter Rakoczy’s Mohawk diploma helped him open doors to become one of the top players in Microsoft’s global empire. In this exclusive interview with In Touch he shares some words of wisdom about the secrets of his success. BY KATE SCHOOLEY LIFE OF THE PARTY 16 Mohawk grad Doug Dreher’s career has blown-up big time. DEPARTMENTS As General Manager of the Pioneer Baloon Company the Welcoming Words. 4 decision to go to Mohawk inflated his career opportunities Alumni News. 6 and left him flying high. BY K. L. SCHMIDT Upcoming Events . 8 Alumni Varsity . 9 STRATEGY FOR SUCCESS Around Campus . 10 Fundraising Update . 14 22 Mohawk President MaryLynn West-Moynes shares her Strategic Plan for keeping Mohawk College at the forefront Keeping In Touch . 36 of education in Ontario. BY KATE SCHOOLEY Looking Back . 38 MOVIN’ ON UP 28 Recent renovations to the Mohawk Student Association ALSO INSIDE aims to increase visibilty of the services the MSA offers MOHAWK IN MEMORIAM 35 to students. BY LYNN JAMES A Fighter, A Friend Mohawk College remembers TURN UP THE HEAT the many contributions that 32 Meet Mohawk Alumnus Chris Dennis, who used his Mohawk Alumnus, and local Mohawk Diploma to help build his family’s business into politician Dominic Agostino a leading-edge supplier of heat-treat services. -

Ontario's Environment and the Common Sense Revolution

Ontarios Environment and the Common Sense Revolution: A Fifth Year Report Canadian Institute for Environmental Law and Policy LInstitut Canadien du Droit et de la Politique de LEnvironnement Acknowledgements Ontarios Environment and the Common Sense For more information about this publication, Revolution: A Fifth Year Report CIELAP or any of CIELAP’s other publications, please consult our website, call us, or write us. By Karen L. Clark LLB MA, Legal Analyst and James Yacoumidis MA, Research Canadian Institute for Associate Environmental Law and Policy 517 College Street, Suite 400 Toronto, Ontario M6G 4A2 The Canadian Institute for Environmental Law and Policy would like to thank the Joyce Foundation for their support for this project. Website: http://www.cielap.org E-mail: [email protected] The authors wish to thank everyone who helped Telephone: 416.923.3529 with this report. Fax: 416.923.5949 Special thanks go to Theresa McClenaghan, Copyright © 2000 Canadian Institute for Environ- CIELAP board member and counsel for the Cana- mental Law and Policy. All rights reserved. Except dian Environmental Law Association for her ex- for short excerpts quoted with credit to the copy- traordinary efforts reviewing this report. right holder, no part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- Special thanks are due as well to Mark Winfield for ted in any form or by any means, photomechanical, his guidance and expertise early in the project and electronic, mechanical, recorded or otherwise for reviewing early drafts. without prior written permission of the copyright holder. We would like to thank our other reviewers: Linda Pim, Tim Gray and Ian Attridge. -

Wed 27 Sep 2000 / Mer 27 Sep 2000

No. 80 No 80 ISSN 1180-2987 Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative of Ontario de l’Ontario First Session, 37th Parliament Première session, 37e législature Official Report Journal of Debates des débats (Hansard) (Hansard) Wednesday 27 September 2000 Mercredi 27 septembre 2000 Speaker Président Honourable Gary Carr L’honorable Gary Carr Clerk Greffier Claude L. DesRosiers Claude L. DesRosiers Hansard on the Internet Le Journal des débats sur Internet Hansard and other documents of the Legislative Assembly L’adresse pour faire paraître sur votre ordinateur personnel can be on your personal computer within hours after each le Journal et d’autres documents de l’Assemblée législative sitting. The address is: en quelques heures seulement après la séance est : http://www.ontla.on.ca/ Index inquiries Renseignements sur l’index Reference to a cumulative index of previous issues may be Adressez vos questions portant sur des numéros précédents obtained by calling the Hansard Reporting Service indexing du Journal des débats au personnel de l’index, qui vous staff at 416-325-7410 or 325-3708. fourniront des références aux pages dans l’index cumulatif, en composant le 416-325-7410 ou le 325-3708. Copies of Hansard Exemplaires du Journal Information regarding purchase of copies of Hansard may Pour des exemplaires, veuillez prendre contact avec be obtained from Publications Ontario, Management Board Publications Ontario, Secrétariat du Conseil de gestion, Secretariat, 50 Grosvenor Street, Toronto, Ontario, M7A 50 rue Grosvenor, Toronto (Ontario) M7A 1N8. Par 1N8. Phone 416-326-5310, 326-5311 or toll-free téléphone : 416-326-5310, 326-5311, ou sans frais : 1-800-668-9938.