File’ in English Speaking Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theofficialorgan of Thebbg

Radio Times, duly 9th, 1926, THE WIRELESS SERMON. i naa a AERO DuAOFES sal (Ea? —_ 7 FONg 7 a IRELae! AEWA ent eames Meat LEFOS-aeaorogo AoE eer | Lever aPoo PRecLay et (ALAI \ ql bayer rigs PanaeeTER eeSHERRIE LO alt get Cia se Promt:ere (Recah we F cea) & a AaTauNGrant S08 40508 LA Lay LonDon ot Prtetas _— pe vnaourtl sntt act | PNEd8T i T R a g e ATTYnn ' : A i aTIT THEOFFICIALORGAN OF THEBBG Thelater cal at Live, Vol.1:12,No. 145, GP. as a Wewepapnr, ‘EVERYFFRIDAY. aes Pence.e. eaiiaeiieetetlicemma ~ -——_—o SS <<— An Editor. Looks at the Mininknnd: By Si ROBERT DONALD, G.B.E., LL.D. HERE is a coming issue which cannot be this direction and the American- Press has newspaper with international athhiations. ignored—the extent to which broad- not been affected by the competition. lts readers, or subscribers, will demand more easting will interiere. with the progress of We are approaching the stage, however, news, and if the Press and news agencies the Press, or change its character. At this put an embargo on the supply, the B.B.C. stage of development, radio is an ally, Will be foreed to collect its own: news af rather than a rival. It i¢ a supplementary all important events. It has been urged service, not an alternative. At first, wireless” that it is beyond the means and the capacity telegraphy was regarded as supplementary of -a broadcasting organization to collect to cables. Now, it is looked upon as a serious foreign news and that &-must temain competitor, Radio is a ‘cheap universal dependent on existing agencies, That is not information, “news, education, and enter- the case, a5 broadcasting stations could tainment service which is delivered into. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 124, 2004-2005

2004-2005 SEASON BOSTON SYM PHONY *J ORCHESTRA JAM ES LEVI N E ''"- ;* - JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK CONDUCTOR EMERITUS SEIJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE Invite the entire string section for cocktails. With floor plans from 2,300 to over Phase One of this 5,000 square feet, you can entertain magnificent property is in grand style at Longyear. 100% sold and occupied. Enjoy 24-hour concierge service, Phase Two is now under con- single-floor condominium living struction and being offered by at its absolute finest, all Sotheby's International Realty & harmoniously located on Hammond Residential Real Estate an extraordinary eight- GMAC. Priced from $1,725,000. acre gated community atop prestigious Call Hammond at (617) 731-4644, Fisher Hill ext. 410. LONGYEAR. a/ l7isner jtfiff BROOKLINE V+* rm SOTHEBY'S Hammond CORTLAND IIIIIIUU] SHE- | h PROPERTIES INC ESTATE 3Bhd International Realty REASON #11 open heart surgery that's a lot less open There are lots of reasons to consider Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like minimally invasive heart surgery that minimizes pain, reduces cosmetic trauma and speeds recovery time. From cardiac services and gastroenterology to organ transplantation and cancer care, you'll find some of the most cutting-edge medical advances available anywhere. To find out more, visit www.bidmc.harvard.edu or call 800-667-5356. Beth Israel A teaching hospital of Deaconess Harvard Medical School Medical Center Red | the Boston Affiliated with Joslin Clinic | A Research Partner of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Official Hospital of James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 124th Season, 2004-2005 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Flyer Zum Festival Aktuelle Musik 017

Mark André, Komponist berlin und die internationale Konzertreihe Zeitzonen, war von 1999 bis 2007 (Composer in Residence 2017) Leiterin des Berliner Ensembles Echo und gründete das ensemble oktopus für musik der moderne an der Hochschule für Musik und Theater München, das Der 1964 in Paris geborene Komponist sie nach wie vor leitet. Konstantia Gourzis kompositorische Arbeit umfasst Mark André schafft in seiner Musik exis- neben Filmmusiken, Werken für Musiktheater, Orchester- und Opernwer- tentielle Erfahrungsräume, die von subtilen ken auch zahlreiche Solo- und Kammermusikstücke. Ihre Kompositionen Veränderungsprozessen geprägt sind. wurden bei internationalen Festivals in Deutschland, Frankreich, Griechen- Nach seinem Studium in Frankreich (u. a. land, Ungarn, Japan, Amerika und Israel aufgeführt. Wichtige Kompositions- bei Claude Ballif und Gérard Grisey) aufträge erhielt sie unter anderem von der Deutschen Oper Berlin, dem absolvierte er von 1993 bis 1996 ein hr-Sinfonieorchester Frankfurt, dem Bayerischen Rundfunk, dem Ensemble weiterführendes Kompositionsstudium bei Helmut Lachenmann an der Musica Nova Israel u.a. Ihre umfassende Discographie beinhaltet CDs ihrer Hochschule für Musik Stuttgart sowie ein Studium der Musikelektronik bei Kompositionen und Aufnahmen von ihr dirigierter Werke. Sie sind u.a. bei André Richard im Experimentalstudio des SWR. Schon bald wurde er mit NEOS, NAXOS, und SONY-Classical erschienen. Ihr Ende 2014 erschienenes Stipendien und Preisen wie dem Kranichsteiner Musikpreis (Darmstädter Debüt-Album bei ECM mit dem Titel Music for String Quartet and Piano fand Ferienkurse 1996), dem 1. Preis des Internationalen Kompositionswettbe- internationale Anerkennung. Im August 2016 debütierte sie beim Lucerne werbs Stuttgart (1997) und dem Kompositionspreis der Oper Frankfurt Festival ebenfalls als Komponistin und Dirigentin mit dem Orchester der (2001) ausgezeichnet. -

Zeitreise Mit Professor Van Dusen

#06 Das JUNI 2021 Magazin Auf der Suche nach dem „Wir“ Ein Essay von Wolfgang Thierse Lesen nonstop Klagenfurt feiert die Literatur Zeitreise mit Professor van Dusen Die Krimiklassiker als Hörspielpodcast Gedruckt oder digital? Das Magazin erscheint nicht nur als gedrucktes Heft, sondern auch in digitaler Version auf deutschlandradio.de/magazin Wie lesen Sie das Magazin am liebsten? Anzeige Beileger_A4_CMYK_RZ.indd 1 20.04.21 15:55 Editorial Veranstaltungen #06 Liebe Abonnentinnen und Abonnenten, wir BERLIN möchten Sie auch in Zukunft gerne über unsere Programme informieren – in Form des gedruckten Magazins oder alternativ online. Daher fragen wir in diesem Monat Ihr Interesse an der Fortführung Ihres Abonnements ab. Mo., 14.6., 20.03 UHR RAUM DRESDEN VON DEUTSCHLANDRADIO, FUNKHAUS BERLIN In Concert Funkhauskonzert mit Peter Licht und Band Live-Übertragung in Deutschlandfunk Kultur Ob in Papierform oder digital – mit dem Magazin KÖLN sind Sie immer Bis 5.9. gut informiert RAUTENSTRAUCH- JOEST-MUSEUM Ausstellung: RESIST! Die Kunst des Widerstands und Denkfabrik-Denkraum mit ausgewählten Hörstücken zum Thema der Denkfabrik 2020 „Eine Welt 2.0 – Neulich fiel mir beim Aufräumen ein 20-bändiger Brockhaus in die Hände, den ich ‚Dekolonisiert Euch!‘“ Ende der 80er-Jahre zu meiner Konfirmation geschenkt bekommen habe. Das war museenkoeln/rauten- damals ein wirklich großes Geschenk, welches mir bei vielen Recherchen gute strauch-joest-museum Dienste geleistet hat. Inzwischen ist es lange her, dass ich eine Information in einem Ausgewählte Veranstal- gedruckten Lexikon nachgeschlagen habe, zu praktisch ist der schnelle Blick ins tungen und Konzerte Internet. werden bei Deutsch- landradio ohne Publikum aufgezeichnet. Diese Überhaupt haben sich Nutzungsgewohnheiten grundlegend verändert. -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 124, 2004-2005

2004-2005 SEASON BOSTON SYM PHONY ORCHESTRA JAMES LEVINE m *x 553 JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK CONDUCTOR EMERITUS SEIJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE Invite the entire string section for cocktails. With floor plans from 2,300 to over Phase One of this 5,000 square feet, you can entertain magnificent property is in grand style at Longyear. 100% sold and occupied. Enjoy 24-hour concierge service, Phase Two is now under con- single-floor condominium living struction and being offered by at its absolute finest, all Sotheby's International Realty d harmoniously located on Hammond Residential Real Estate an extraordinary eight- GMAC Priced from $1,725,000. acre gated community atop prestigious Call Hammond at (617) 731-4644, Fisher Hill ext. 410. LONGYEAR a/ Jisner JH:ill BROOKLINE CORTLAND SOTHEBY'S Hammond PROPERTIES INC. International Realty REAL ESTATE m4WH "nfaBBOHnirAn11 Hfl Partners McLean Hospital is the largest psychiatric facility of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate HEALTHCARE of Massachusetts General Hospital and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #11 open heart surgery that's a lot less open There are lots of reasons to consider Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like minimally invasive heart surgery that minimizes pain, reduces cosmetic trauma and speeds recovery time. From cardiac services and gastroenterology to organ transplantation and cancer care, you'll find some of the most cutting-edge medical advances available anywhere. To find out more, visit www.bidmc.harvard.edu or call 800-667-5356. Israel A teaching hospital of Beth Deaconess Harvard Medical School Medical Center Affiliated Re with Joslin Clinic | A Research Partner of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center | Official Hospital of the Boston ^^^^^^^^^^^1 James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 124th Season, 2004-2005 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France. -

Gala Fundraising Event of the American Friends Of

Contact Valentina Rota Executive Director Foundation Friends of LUCERNE FESTIVAL Director of Development American Friends of LUCERNE FESTIVAL International Private Fundraising Hirschmattstrasse 13 | CH–6002 Lucerne t +41 (0)41 226 44 52 (CH) | t +1 917-710-1956 (USA) [email protected] | [email protected] Gala Fundraising Event of the American Friends of LUCERNE FESTIVAL Save the Date, Pricing Details, and Information Monday, May 9, 2016 Carnegie Hall 881 7th Avenue, New York City LUCERNE FESTIVAL / Photo: Stefan Deuber © For more information: Vontobel is a proud partner of the American Friends of [email protected] LUCERNE FESTIVAL, represented by Vontobel Asset Management Inc. and Vontobel Swiss Wealth Advisors AG. www.lucernefestival.ch +1 917-710-1956 It is the mission of the American Friends of LUCERNE FESTIVAL to allow the most talented music students from the leading conservatories in the United States to attend the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY and to provide financial support to permit the best American orchestras and artists to perform at LUCERNE FESTIVAL. Gala Fundraising Event of the American Friends of LUCERNE FESTIVAL Save the Date, Pricing Details, and Information LUCERNE FESTIVAL / Photo: Priska Ketterer © 3 4 INDEX 8 Editorial 10 American Friends of LUCERNE FESTIVAL 11 Pricing details 16 About LUCERNE FESTIVAL 19 About the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY 22 Lucerne 5 6 editOrial Dear Music Lovers Almost one third The LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY is a unique and of the top young exceptional Summer Academy for young, highly talented musicians attending musicians from around the globe who are introduced the LUCERNE to the mysteries of modern and contemporary works. -

NEWSLETTER > 2019

www.telmondis.fr NEWSLETTER > 2019 Opera Dance Concert Documentary Circus Cabaret & magic OPERA OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS > Boris Godunov 4 > Don Pasquale 4 > Les Huguenots 6 SUMMARY > Simon Boccanegra 6 OPÉRA DE LYON DANCE > Don Giovanni 7 OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS TEATRO LA FENICE, VENICE > Thierrée / Shechter / Pérez / Pite 12 > Tribute to Jerome Robbins 12 > Tannhäuser 8 > Cinderella 14 > Orlando Furioso 8 > Norma 9 MALANDAIN BALLET CONCERT > Semiramide 9 > Noah 15 OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS DUTCH NATIONAL OPERA MARIINSKY THEATRE, ST. PETERSBURG > Tchaikovsky Cycle (March 27th and May 15th) 18 > Le Nozze de Figaro 10 > Petipa Gala – 200th Birth Anniversary 16 > The 350th Anniversary Inaugural Gala 18 > Der Ring des Nibelungen 11 > Raymonda 16 BASILIQUE CATHÉDRALE DE SAINT-DENIS > Processions 19 MÜNCHNER PHILHARMONIKER > Concerts at Münchner Philharmoniker 19 ZARYADYE CONCERT HALL, MOSCOW > Grand Opening Gala 20 ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC > 100th Anniversary of Gara Garayev 20 > Gala Concert - 80th Anniversary of Yuri Temirkanov 21 ALHAMBRA DE GRANADA > Les Siècles, conducted by Pablo Heras-Casado 22 > Les Siècles, conducted by François-Xavier Roth 22 > Pierre-Laurent Aimard’s Recital 23 OPÉRA ROYAL DE VERSAILLES > La Damnation de Faust 23 DOCUMENTARY > Clara Haskil, her mystery as a performer 24 > Kreativ, a study in creativity by A. Ekman 24 > Hide and Seek. Elīna Garanča 25 > Alvis Hermanis, the last romantic of Europe 25 > Carmen, Violetta et Mimi, romantiques et fatales 25 CIRCUS > 42nd international circus festival of Monte-Carlo 26 -

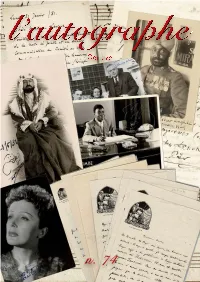

Genève L’Autographe

l’autographe Genève l’autographe L’autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201 Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in EURO and do not include postage. All overseas shipments will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefts of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, Paypal and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfnance CCP 61-374302-1 3, rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: CH 94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped via Federal Express on request. Music and theatre p. 4 Miscellaneous p. 38 Signed Pennants p. 98 Music and theatre 1. Julia Bartet (Paris, 1854 - Parigi, 1941) Comédie-Française Autograph letter signed, dated 11 Avril 1901 by the French actress. Bartet comments on a book a gentleman sent her: “...la lecture que je viens de faire ne me laisse qu’un regret, c’est que nous ne possédions pas, pour le Grand Siècle, quelque Traité pareil au vôtre. Nous saurions ainsi comment les gens de goût “les honnêtes gens” prononçaient au juste, la belle langue qu’ils ont créée...”. 2 pp. In fine condition. € 70 2. Philippe Chaperon (Paris, 1823 - Lagny-sur-Marne, 1906) Paris Opera Autograph letter signed, dated Chambéry, le 26 Décembre 1864 by the French scenic designer at the Paris Opera. -

Adrian Brown Leader – Andy Laing Violin Solo – Anna-Liisa Bezrodny

Conductor – Adrian Brown Leader – Andy Laing Violin solo – Anna-Liisa Bezrodny Saturday 10th March 2018 Langley Park Centre for the Performing Arts £ 1 . 50 . www.bromleysymphony.org Box office: 020 3627 2974 Registered Charity N o 1112117 PROGRAMME Smetana Overture: The Bartered Bride Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Soloist: Anna-Liisa Bezrodny INTERVAL - 20 MINUTES Refreshments are available in the dining hall. Shostakovich Symphony No.15 Unauthorised audio or video recording of this concert is not permitted Our next concert is on May 19 th at the Langley Park Centre for the Performing Arts: Bernstein Overture ‘Candide’, Roy Harris Symphony No. 3, Holst ‘The Planets’ Suite First performed in 1918 under the baton of Sir Adrian Boult and now conducted in 2018 by his pupil Adrian Brown. ADRIAN BROWN – MUSIC DIRECTOR Adrian Brown comes from a distinguished line of pupils of Sir Adrian Boult. After graduating from the Royal Academy of Music in London, he studied intensively with Sir Adrian for some years. He remains the only British conductor to have reached the finals of the Karajan Conductors’ Competition and the Berlin Philharmonic was the first professional orchestra he conducted. Sir Adrian said of his work: “He has always impressed me as a musician of exceptional attainments who has all the right gifts and ideas to make him a first John Carmichael class conductor”. In 1992 Adrian Brown was engaged to conduct one of the great orchestras of the world, the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1998 he was invited to work with the Camerata Salzburg, one of Europe’s foremost chamber orchestras at the invitation of Sir Roger Norrington.