Chapter 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Root Weevils Ryan Davis Arthropod Diagnostician

Published by Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory ENT-193-18 May 2018 Root Weevils Ryan Davis Arthropod Diagnostician Quick Facts • Root weevils are a group of small, black-to-brown weevils that commonly damage ornamental and small fruit plants in Utah. • Adult root weevil damage is characterized by marginal leaf notching and occasional feeding on buds and young shoots. • Larval root weevil damage occurs below ground; damage to roots can lead to canopy decline or plant death. • Root weevils are occasional nuisance pests in homes and structures mid-summer through fall. • Manage root weevil larvae by applying a systemic insecticide to the soil around host plants April through September. • Adults feeding on the above-ground portion of plants can be targeted with pyrethroid pesticides Black vine weevil adult (Kent Loeffler, Cornell University, Bugwood.org) starting in late June or early July. IDENTIFICATION INTRODUCTION Root weevils are small beetles ranging in length from about 1/4 to 1/3 inch depending on The black vine weevil (Otiorhynchus sulcatus), species. Coloration is variable, but the commonly lilac root weevil (O. meridionalis) strawberry weevil encountered species in Utah are black with gold (O. ovatus) and rough strawberry root weevil (O. flecks (black vine weevil) or solid brown to black, rugosostriatus) are a complex of non-native, snout- shiny or matte. As a member of the weevil family nosed beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) that (Curculionidae), these pests have a snout, but it cause damage to ornamentals and small fruit crops is shortened and rectangular compared to other in Utah. Root weevils are occasional nuisance pests weevils that have long, skinny mouthparts. -

Root Weevils Fact Sheet No

Root Weevils Fact Sheet No. 5.551 Insect Series|Home and Garden by W.S. Cranshaw* None of the root weevils can fly and A root weevil is a type of “snout beetle” they are night active, hiding during the Quick Facts that develops on the roots of various plants. day around the base of host plants, usually Adult stages produce more conspicuous under a bit of cover. About an hour after • Root weevils can be common plant damage, cutting angular notches along sunset they become active and crawl onto insects that develop on roots the edge of leaves when they feed at night. the plants to feed on leaves, producing their of many garden plants. Adult root weevils also may attract attention characteristic angular notches. If disturbed, • Adult root weevils chew when they wander into buildings, acting as a root weevils will readily drop from plants and distinctive notches along the temporary “nuisance invader”. play dead. The most common root weevils found Adults typically live for at least a couple edges of leaves at night. in Colorado are strawberry root weevil of months, and some may be present into • Some kinds of root weevils (Otiorhynchus ovatus), rough strawberry autumn. Most eggs are laid in late spring and often wander into homes but root weevil (O. rugostriatus), black vine early summer with females squeezing eggs cause no injury indoors. weevil (O. sulcatus) and lilac root weevil into soil cracks. A few days after they are (O. meridionalis). Dyslobus decoratus is laid, eggs hatch and the larvae move to the • Insecticides applied on the established in some areas and chews leaves roots where they feed. -

On the Establishment of the Cribrate Weevil, Otiorhynchus Cribricollis Gyllenhal, in Hawaii ( Coleoptera: Curculionidae )X

Vol. XVIII, No. 1, August, 1962 189 On the Establishment of the Cribrate Weevil, Otiorhynchus cribricollis Gyllenhal, in Hawaii ( Coleoptera: Curculionidae )x Elwood C. Zimmerman HUNTER HOUSE, MACDOWELL ROAD PETERBOROUGH, NEW HAMPSHIRE {Submitted for publication December, 1961) A weevil new to the Hawaiian fauna has been discovered on the island of Hawaii, and I have identified the specimen submitted to me for examination as the widespread pest known as the cribrate weevil. Otiorhynchus2 cribricollis Gyllenhal (Figure 1). Otiorhynchus cribricollis Gyllenhal, in Schoenherr, 1834, Genera et Species Curculionidum 2(l):582. Brachyrhinus cribricollis (Gyllenhal), of authors. See C. Lona, 1936, Coleopterorum Catalogus 148:165-166, for synonymy, bibliography, and notes. Fig. 1. Otiorhynchus cribricollis Gyllenhal, length 9.5 mm. (HSPA Photo.) 1 Prepared during the tenure of National Science Foundation Grant G-18933, "Pacific Island Weevil Studies." 2 I prefer to use the original spelling Otiorhynchus instead of Otiorrhynchus as amended by Gemminger and Harold, 1871. 190 Proceedings, Hawaiian Entomological Society One adult was collected in association with larvae which were feeding in roots of "gobo" (Arctium lappa or great burdock) at Onodera Farm, near Kamuela, Hawaii, June 2, I960, by Minoru Matsuura. This broad-nosed weevil is a native of the Mediterranean region of Europe, from where it has been spread by man to various regions, including parts of America and Australia. It is probable that it was introduced to Hawaii from California. Albert Koebele, well-known early entomologist in Hawaii, first found the weevil in Australia at Adelaide in 1890, and it has since become a pest of economic importance there. -

IOBC/WPRS Working Group “Integrated Plant Protection in Fruit

IOBC/WPRS Working Group “Integrated Plant Protection in Fruit Crops” Subgroup “Soft Fruits” Proceedings of Workshop on Integrated Soft Fruit Production East Malling (United Kingdom) 24-27 September 2007 Editors Ch. Linder & J.V. Cross IOBC/WPRS Bulletin Bulletin OILB/SROP Vol. 39, 2008 The content of the contributions is in the responsibility of the authors The IOBC/WPRS Bulletin is published by the International Organization for Biological and Integrated Control of Noxious Animals and Plants, West Palearctic Regional Section (IOBC/WPRS) Le Bulletin OILB/SROP est publié par l‘Organisation Internationale de Lutte Biologique et Intégrée contre les Animaux et les Plantes Nuisibles, section Regionale Ouest Paléarctique (OILB/SROP) Copyright: IOBC/WPRS 2008 The Publication Commission of the IOBC/WPRS: Horst Bathon Luc Tirry Julius Kuehn Institute (JKI), Federal University of Gent Research Centre for Cultivated Plants Laboratory of Agrozoology Institute for Biological Control Department of Crop Protection Heinrichstr. 243 Coupure Links 653 D-64287 Darmstadt (Germany) B-9000 Gent (Belgium) Tel +49 6151 407-225, Fax +49 6151 407-290 Tel +32-9-2646152, Fax +32-9-2646239 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Address General Secretariat: Dr. Philippe C. Nicot INRA – Unité de Pathologie Végétale Domaine St Maurice - B.P. 94 F-84143 Montfavet Cedex (France) ISBN 978-92-9067-213-5 http://www.iobc-wprs.org Integrated Plant Protection in Soft Fruits IOBC/wprs Bulletin 39, 2008 Contents Development of semiochemical attractants, lures and traps for raspberry beetle, Byturus tomentosus at SCRI; from fundamental chemical ecology to testing IPM tools with growers. -

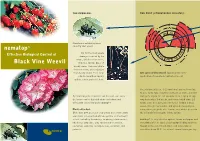

Nematop® Black Vine Weevil

THE PROBLEM: THE PEST (OTIORHYNCHUS SULCATUS): Ju un l A J ug y a S e M p Characteristic notching of leaves r O p caused by adult weevils. c ® A t r N nematop a o M By far the most severe v b D Effective Biological Control of e e F damage is caused by the c n J larvae, which feed on roots, a Black Vine Weevil rhizomes and the bases of woody stems. They may girdle the root crown, and strip bark from woody stems. Even large Life cycle of vine weevil (Optimum times for plants can wither and die application of nematodes indicated in red) within a short period of time. The adult weevils (ca. 8-13 mm long) emerge from late May to early July. They feed on leaves at night, and hide By examining the stem base and the root-zone area, during the day in the soil or under litter. Laying of eggs the larvae can be detected at an early stage and may begin after 3-4 weeks, and larvae hatch some 2-3 effectively controlled with nematop®! weeks later. Root damage from larval feeding is most severe through the autumn, and again in the spring as Plants attacked: temperatures begin to rise. Larvae over-winter deeper in More than 200 species of crop plants and ornamentals the soil and finally pupate in late spring. are known to be particularly susceptible to vine weevil attack, including strawberry, raspberry, blackcurrant, nematop® is only effective against larvae and pupae and blueberry, grapevine, yew, rhododendron, azalea, should therefore be applied during April / May and from euonymus, camellia, cyclamen, rose, geranium, and August to the end of September. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0099135A1 Enan (43) Pub

US 20090099.135A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0099135A1 Enan (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 16, 2009 (54) PEST CONTROL COMPOSITIONS AND Publication Classification METHODS (51) Int. Cl. AOIN 57/6 (2006.01) AOIN 47/2 (2006.01) (75) Inventor: Essam Enan, Davis, CA (US) AOIN 43/12 (2006.01) AOIN 57/4 (2006.01) AOIN 53/06 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: AOIN 5L/00 (2006.01) SONNENSCHEN NATH & ROSENTHAL LLP AOIN 43/40 (2006.01) AOIP3/00 (2006.01) P.O. BOX 061080, WACKER DRIVE STATION, AOIP 7/04 (2006.01) SEARS TOWER AOIP 7/02 (2006.01) CHICAGO, IL 60606-1080 (US) AOIN 43/90 (2006.01) AOIN 43/6 (2006.01) AOIN 43/56 (2006.01) (73) Assignee: TyraTech, Inc., Melbourne, FL AOIN 29/2 (2006.01) (US) AOIN 43/52 (2006.01) AOIN 57/12 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. ........... 514/86; 514/477; 514/469; 514/481; (21) Appl. No.: 12/009,220 514/395; 514/122:514/89: 514/486; 514/132: 514/748; 514/520; 514/531; 514/.407: 514/365; 514/341; 514/453: 514/343; 514/299 (22) Filed: Jan. 16, 2008 (57) ABSTRACT Embodiments of the present invention provide compositions for controlling a target pest including a pest control product Related U.S. Application Data and at least one active agent, wherein: the active agent can be capable of interacting with a receptor in the target pest; the (60) Provisional application No. 60/885,214, filed on Jan. pest control product can have a first activity against the target 16, 2007, provisional application No. -

Biology, Distribution and Economic Thresholdof

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Joseph Francis Cacka for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology presented on February 1, 1982 Title: BIOLOGY, DISTRIBUTION AND ECONOMICTHRESHOLD OF THE STRAWBERRY ROOT WEEVIL, OTIORHYNCHUS OVATUS (L.),IN PEPPERMINT Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Rarph E. Berryd-- This study of the strawberryroot weevil, Otiorhynchus ovatus (L.), on peppermint, Mentha piperita (L.), incentral Oregon provided biological information toassess economic importance and to develop a sequential sampling plan. Teneral adult weevils emergedfrom the soil from late May until late July. Oviposition of new generation adultscommenced in early July. A minimum 12 day egg incubationperiod was observed. Larvae were present in peppermint fields allyear and were the dominant life stage from late August until mid-Maythe following year. Pupation commenced during early to mid-May andwas completed by late June.Overwintered adults were found in spring samplesat densities not greater than 11.6% of the sampled population. Developed ova were observed in theover- wintered adults in late May. A carabid beetle, Pterostichus vulgaris (L.), was predaceouson larval, pupal and adult strawberry root weevils, no other predators or parasiteswere observed. Fall plowing of peppermint fieldsincreased the depth at which weevils were found the followingspring. When fields are sampled in mid-May, a minimum depth of 15cm is suggested for fall plowed fields and ten cm for unplowed fields. Strawberry root weevil adults,pupae, larvae and the total of all these life stages havea clumped distribution that fit the negative binomial distribution whensufficient data were available to determine frequency distributions. Statistically significant negativerelationships were found between pupae, larvae and the total strawberryroot weevil population and peppermint oil yields. -

Practical Black Vine Weevil Management

Practical Black Vine Weevil Management Source: JARS V57:No4:p219:y2003 Practical Black Vine Weevil Management Richard S. Cowles Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Valley Laboratory P. O. Box 248 Windsor, CT 06095 Black vine weevil, Otiorhynchus sulcatus F, is the most obviously injurious insect pest of rhododendrons. Rhododendron enthusiasts are disheartened when purchasing precious species or hybrid plants, if they then find that the plant came with unwanted weevils "hitchhiking" in the roots. If the plant is small, feeding by black vine weevil larvae may cause sufficient root loss to kill the plant, or the larvae may girdle the main stem, with the same result. Larger plants can be affected in other ways. Root feeding can lead to nutrient deficiencies, because poorly functioning roots cannot translocate minerals available in the soil to the foliage. Finally, adult black weevils give plants a ragged appearance by notching the edges of leaves while feeding. This article is an update to my earlier review of black vine weevil biology (Cowles, 1995), and suggests practical approaches for managing this pest in nursery and landscape settings. Management in Container-grown Nurseries Control of black vine weevils in nurseries is especially important, both for protecting plants and to prevent transport of this pest. During the early development of rhododendron plants, there is insufficient root tissue on an individual plant to support the development of black vine weevil larvae, leading to plant girdling (Cowles, 1995). I have observed long-term effects of partial girdling and root loss on the growth performance of nursery plants, so any early effort to prevent this feeding can be expected to yield large benefits in terms of improved plant growth. -

Comparison of Invertebrates and Lichens Between Young and Ancient

Comparison of invertebrates and lichens between young and ancient yew trees Bachelor agro & biotechnology Specialization Green management 3th Internship report / bachelor dissertation Student: Clerckx Jonathan Academic year: 2014-2015 Tutor: Ms. Joos Isabelle Mentor: Ms. Birch Katherine Natural England: Kingley Vale NNR Downs Road PO18 9BN Chichester www.naturalengland.org.uk Comparison of invertebrates and lichens between young and ancient yew trees. Natural England: Kingley Vale NNR Foreword My dissertation project and internship took place in an ancient yew woodland reserve called Kingley Vale National Nature Reserve. Kingley Vale NNR is managed by Natural England. My dissertation deals with the biodiversity in these woodlands. During my stay in England I learned many things about the different aspects of nature conservation in England. First of all I want to thank Katherine Birch (manager of Kingley Vale NNR) for giving guidance through my dissertation project and for creating lots of interesting days during my internship. I want to thank my tutor Isabelle Joos for suggesting Kingley Vale NNR and guiding me during the year. I thank my uncle Guido Bonamie for lending me his microscope and invertebrate books and for helping me with some identifications of invertebrates. I thank Lies Vandercoilden for eliminating my spelling and grammar faults. Thanks to all the people helping with identifications of invertebrates: Guido Bonamie, Jon Webb, Matthew Shepherd, Bryan Goethals. And thanks to the people that reacted on my posts on the Facebook page: Lichens connecting people! I want to thank Catherine Slade and her husband Nigel for being the perfect hosts of my accommodation in England. -

SCI Insectsurveys Report.Fm

Terrestrial Invertebrate Survey Report for San Clemente Island, California Final June 2011 Prepared for: Naval Base Coronado 3 Wright Avenue, Bldg. 3 San Diego, California 92135 Point of Contact: Ms. Melissa Booker, Wildlife Biologist Under Contract with: Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Southwest Coastal IPT 2739 McKean Street, Bldg. 291 San Diego, California 92101 Point of Contact: Ms. Michelle Cox, Natural Resource Specialist Under Contract No. N62473-06-D-2402/D.O. 0026 Prepared by: Tierra Data, Inc. 10110 W. Lilac Road Escondido, CA 92026 Points of Contact: Elizabeth M. Kellogg, President; Scott Snover, Biologist; James Lockman, Biologist COVER PHOTO: Halictid bee (Family Halictidae), photo by S. Snover. Naval Auxiliary Landing Field San Clemente Island June 2011 Final Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction . .1 1.1 Regional Setting ................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project Background .............................................................................................................. 1 1.2.1 Entomology of the Channel Islands .................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Feeding Behavior of Key Vertebrate Predators on San Clemente Island ............. 4 1.2.3 Climate ................................................................................................................. 4 1.2.4 Island Vegetation.................................................................................................. 5 -

An Annotated List of Insects and Other Arthropods

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Invertebrates of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, Western Cascade Range, Oregon. V: An Annotated List of Insects and Other Arthropods Gary L Parsons Gerasimos Cassis Andrew R. Moldenke John D. Lattin Norman H. Anderson Jeffrey C. Miller Paul Hammond Timothy D. Schowalter U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon November 1991 Parson, Gary L.; Cassis, Gerasimos; Moldenke, Andrew R.; Lattin, John D.; Anderson, Norman H.; Miller, Jeffrey C; Hammond, Paul; Schowalter, Timothy D. 1991. Invertebrates of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, western Cascade Range, Oregon. V: An annotated list of insects and other arthropods. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-290. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 168 p. An annotated list of species of insects and other arthropods that have been col- lected and studies on the H.J. Andrews Experimental forest, western Cascade Range, Oregon. The list includes 459 families, 2,096 genera, and 3,402 species. All species have been authoritatively identified by more than 100 specialists. In- formation is included on habitat type, functional group, plant or animal host, relative abundances, collection information, and literature references where available. There is a brief discussion of the Andrews Forest as habitat for arthropods with photo- graphs of representative habitats within the Forest. Illustrations of selected ar- thropods are included as is a bibliography. Keywords: Invertebrates, insects, H.J. Andrews Experimental forest, arthropods, annotated list, forest ecosystem, old-growth forests. -

(Vaccinium Corymbosum) EN LA ARGENTINA

Naturalis Repositorio Institucional Universidad Nacional de La Plata http://naturalis.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo Diversidad de los artrópodos fitófagos del cultivo de arándano [Vaccinium corymbosum] en la Argentina Rocca, Margarita Doctor en Ciencias Naturales Dirección: Mareggiani, Graciela Co-dirección: Greco, Nancy Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo 2010 Acceso en: http://naturalis.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar/id/20120126001027 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) A mi familia mis papás Marta y Alejandro mis hermanos Tere, Ale, Fran y Pedro por siempre alentarme a seguir creciendo… 2 Índice ÍNDICE ÍNDICE ............................................................................................................................. 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS .................................................................................................... 7 RESUMEN ....................................................................................................................... 9 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................... 13 Sección A ....................................................................................................................... 17 Organización de la Tesis................................................................................................. 17 CAPÍTULO I INTRODUCCIÓN GENERAL .....................................................................................