Collective Remembering and the Structure of Settler Colonialism in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Order in Council 282/1981

BRITISH COLUMBIA 282 APPROVED AND ORDERED -4.1981 JFL ieutenant-Governor EXECUTIVE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, VICTORIA FEB. -4.1981 On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant-Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that the trans fer of the interest of the Crown in the lands, equipment and property in items 6, 11 and 15 in the Schedule' titled Victoria Land Registration District in order in council 1131/79Jis resc inded. Provincial Secretary and Minister of Government Services Presiding Member of t ye Council ( Thu part ii for administrative purposes and is riot part o/ the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: British Columbia Buildings Corporation Act, a. 15 Act and section Other (specify) R. J. Chamut Statutory authority checked by . .... ...... _ _ . .... (Signature and typed or firtnWd name of Legal °Aker) January 26, 1981 4 2/81 1131 APPROVED AND ORDERED Apa ion 444114,w-4- u EXECUTIVE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, VICTORIA kpR. 121979 On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant-Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that 1. the Lands listed on the Schedules attached hereto be hereby transferred to the British Columbia Buildings Corporation together with all equipment, movable and immovable property as may be on or related to the said Lands belonging to the Crown. 2. the Registrar of the Land Registry Office concerned, on receipt of a certified copy of this Order—in—Council, make all necessary amendments to the register as required under Section 14(2) of the British Columbia Buildings Corporation Act. -

Arctic Indigenous Economies Arctic and International Relations Series

Spring 2017, Issue 5 ISSN 2470-3966 Arctic and International Relations Series Arctic Indigenous Economies Canadian Studies Center Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington, Seattle Contents PREFACE pg. 5 WELCOMING REMARKS FROM THE DIRECTOR OF THE HENRY M. JACKSON SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES pg. 8 KEYNOTE ADDRESS BY THE CONSUL GENERAL OF CANADA, SEATTLE pg. 9 ARCTIC INDIGENOUS ECONOMIES WORKSHOP PRESENTATIONS pg. 15 Business in the Arctic: Where to Begin? pg. 16 Jean-François Arteau Avataa Explorations and Logistics: Mindful Business Practices pg. 22 Nadine Fabbi in Conversation with Charlie Watt and Christine Nakoolak Makivik Corporation: The Promotion of Inuit Tradition through Economic Development pg. 27 Andy Moorhouse Co-Management of New and Emerging Fisheries in the Canadian Beaufort Sea pg. 31 Burton Ayles Nunatsiavut and the Road to Self-Governance pg. 37 Nunatsiavut Government PART 2: ARCTIC INDIGENOUS ECONOMIES VIDEO SERIES TRANSCRIPTS pg. 41 Traditional Knowledge and Inuit Law pg. 43 Jean-François Arteau with Malina Dumas Insights from Avataa Explorations and Logistics pg. 45 Charlie Watt and Christine Nakoolak Part I: Impacts of Global Warming, with Olivier Ndikumana Part II: Building Mindfulness and Pride in Nunavik, with Lucy Kruesel Makivik Corporation: Fortieth Anniversary and Beyond pg. 47 Andy Moorhouse with Brandon Ray Fisheries Management and Climate Change pg. 49 Burton Ayles with Katie Aspen Gavenus Parks Management and Tourism in Nunatsiavut pg. 52 Minister Sean Lyall with Elizabeth Wessells and Elena Bell ARCTIC INDIGENOUS ECONOMIES 3 Contents, continued PART 3: INTERNATIONAL POLICY INSTITUTE ARCTIC FELLOWS pg. 55 CLIMATE CHANGE AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT pg. 56 The More We Act, the More We Save Our Global Air Conditioning, the Arctic pg. -

An Act for the Redistribution of British Columbia Into Electoral Districts

1902. REDISTBIBUTION. CHAP. 58. CHAPTER 58. An Act for the Redistribution of British Columbia into Electoral Districts. \%%nd April, 1902.] IS MAJESTY, by and with the advice and consent of the Legis H lative Assembly of the Province of British Columbia, enacts as follows:— 1. This Act may be cited as the "Redistribution Act, 1902." Short title. '&. Sections 5 and 6, of Chapter 67 of the " Revised Statutes," and Repeal Clauses, sections 3 to 18, both inclusive, and 20 and 21 of Chapter 38 of the Statutes of 1898, are hereby repealed. 3. For the returning the number of Members of the Legislative Electoral Districts. Assembly of the Province of British Columbia fixed by the " Consti tution Act," there shall be and there are hereby created and established the following Electoral Districts, the names and boundaries whereof shall be those hereinafter described and defined in the following sub sections, and which Districts shall severally return to the Assembly the number of Members prescribed by the said sub-sections, that is to say:— VICTORIA CITY ELECTORAL DISTRICT. (1.) That tract of land comprised within the municipality of the Victoria City. limits of the City of Victoria, including all that piece or parcel of land described and defined as follows:— Commencing at a point on the shore line of Foul Bay at the southern end of an accommodation road; thence northerly along the centre of said road to its intersection with the southern boundary line of section 68; thence easterly along said boundary line to the south-east corner of section 68; thence northerly along the eastern boundary lines of sections 68, 74, and 76 to the south-east corner of section 25; thence 217 CHAP. -

BC First Nations During the Period of the Land-Based Fur Trade up to Confederation

intermediate/senior mini unit http://hcmc.uvic.ca/confederation/ British Columbia Provincial Edition 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................1 ABOUT THE CONFEDERATION DEBATES MINI-UNIT ..........................................................................3 CURRICULUM OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................................4 Civic Studies 11 ..................................................................................................................................4 First Nations Studies 12 .....................................................................................................................4 SECTION 1 | CREATING CANADA: BRITISH COLUMBIA ......................................................................6 Prerequisite Skillset ...........................................................................................................................6 Background Knowledge.....................................................................................................................6 Confederation Debates: Introductory Lesson ...................................................................................7 Confederation Debates: Biographical Research ...............................................................................9 Culminating Activity: The Debate ...................................................................................................11 -

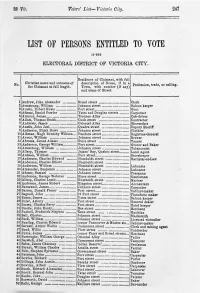

List of Persons Entitled to Vote

as Vie. Vote1'S'-List-Victoria Cily. 247 LIST OF PERSONS ENTITLED TO VOTE iN THE ELECTORAL DISTRICT OF VICTORIA CITY. Residence of Claimant, with full No. Christian name and surname of description of House, if in a Profession, trade, or ca.lling. the Claimant at full length. Town, with number (if any) and name of Street. \ 1 Andrew , John Alexander , ............ Broad street ........................... Clerk 2 Armstrong, William .................. Johnson street ....................... Saloon keeper 3 Austin, Robert Howe .................. Fort ,street .............................. Gent 4 Adams, Daniel Fowler ............... Yates and Douglas streets ......... Oarpenter 5 Armour, Jam~s ........................... Trounce Alley.; .... .................. ·Cab-driver 6 Allatt, Thomas Smith .................. Cook street ........................... Contractor 'i Andrews, James ........................ Oriental Alley ........................ Sboemaker 8 Austin, J ohn Joel. ....................... Quadra street ........................ Deputy Sheriff 9 Anderson, Elijah Howe ............... Johnson street ........................ Olothier 10 Aikman, Hugh Bowlsby Willson ... Pandora street ........................ Registrar-Gellera! 11 Avons, William ........................ Johnson street ........................ Brewer 12 Abrams, James Adams ............... Store street ........................... Tanner 13 Anderson, George William ............ Fort street .............................. Grocer and Baker 14 Armstrong, William ................. -

The London Gazette, May 19, 1871

2392 THE LONDON GAZETTE, MAY 19, 1871. Lord Chamberlain*s Office, St. James's Palace., nated " New Westminster District," and March 24, 1871. return onj member. "" Cariboo District" and " Lillooet Dis- OTICE is hereby given, that Her Majesty's trict," as specified in the said public no- N Birthday will be kept on Saturday, the tice, shall constitute one district, to be 20th of May next. designated " Cariboo District," and re- turn one member. " Tale District " and " Kootenay District," as specified in the said public notice, shall T the Court at Windsor, the 16th day of constitute one district, to be designated A' May, 1871. "Tale District," and return one member. 7 Those portions of Vancouver Island, known PEESE^ T, as " Victoria District," " Esqiiima.lt Dis- The QUEEN'S Most Excellent Majesty. trict," and " Metchosin District," as de- His Eoyal Highness Prince AETHUE. fined in the official maps of those dis- tricts which are in the Land Office, UbroTPrivy"SealY ' "Lord'Chamberlain. .Victoria, and are designated respectively, Earl Cowper. Mr. Secretary Card well. "Victoria District Official Map, 1858," Earl of Kimberley. Mr. Ayrton. " Esquimalt District Official Map, 1858," and "Metchosin District Official Map, £/Y7KEEEAS by the "British North America. A..D. 1858," shall constitute one district, » v Act, 1SG7," provision was made for the to be designated " Victoria District," and Union of the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia return two members. and New Brunswick into the Dominion of AILthe remainder of Vancouver Island, and Canada, and it was (amongst other, things) enacted all such islands adjacent thereto, as were that, it- should be lawful .for the Queen, by formerly dependencies.of the late Colony and with the advice of Her . -

British Columbia July 2007 Voters’ Lists

DATE Title/ British Columbia July 2007 Voters’ Lists Understanding the format of the Voters’ lists binder The pages are a table of content for the volumes. Electoral districts listed in order of appearance. Populations are divided into electoral districts. Ridings and/or polling divisions may be listed. Corresponding index precedes each voters’ list. The date accompanying the district name is either the enumeration date or Court of Revision date as shown on first or last page of voters’ lists. The small black number following the district is the date of either the Enumeration or Court of Revision. DATE Condition/s & Title/ Electoral Districts Description stable List of Voters…British Columbia [as listed] 1874 condition Enumerated Victoria City 1874:08.01 1874: July - Aug Esquimalt District 1874:08.01 One Polling Divisions:Esquimalt [incl.Highlands/Metchosin], rebound Sooke hardcover Victoria District 1874:07.28 Polling Divisions: Victoria, volume North Saanich, [rebinding encompasses South Saanich, Lake District original fragile paper covers] Cowichan District 1874:08.01 inclusive Polling Divisions: Cowichan, of these Salt Spring Island districts Nanaimo District 1874:08.01 Comox District 1874:08.01 Cariboo District 1874:08.01 Polling Divisions: Barkerville, Harvey & Keithley, Quesnellemouth, Williams Lake, Omineca, Lightning Creek 1874:08.03 Kootenay District Polling Divisions: Wild Horse Creek, Perry Creek Lillooet District 1874:08.01 Polling Divisions: Canoe Creek, Clinton Yale District 1874:08.01- 1874:08.06 Polling Divisions: Hope & Yale, Lytton, Nicola, Okanagan, Cache Creek, Kamloops New Westminster City 1874:08.01 New Westminster District 1874:07.21- Polling Divisions: New Westminster, 1874:08.01 North Arm, South Arm, Burrard Inlet, Chilliwhack [sic] & Sumass [sic[, Langley 7. -

Bcsp Index Intro/Contents

British Columbia Sessional Papers Index, 1872-1916 INTRODUCTION The British Columbia Sessional Papers are an annual collection of selected papers tabled in the Legislative Council of British Columbia (2nd to 8th Sessions, 1865-1871) and the Legislative Assembly (1st to 32nd Parliaments, 1872-1982). This index covers Sessional Papers published between 1865 and 1871 with the Journals of the British Columbia Legislative Council; the term Sessional Papers first appeared in the 1866 Journals. The index partially fulfills a requirement for an index to the complete set of Sessional Papers. Departmental reports and selected papers published in the Sessional Papers are also indexed in Marjorie C. Holmes' Publications of the Government of British Columbia, 1871-1947 (BC Archives Library call no. Ref. NW 016.9711 H752p). A photocopied set of table of content pages for all BC Sessional Papers is available via the Information Desk in the BC Archives Reference Room. The following special categories of papers are indexed under the headings in parentheses: (Acts): also indexed by subject matter (Indexes): to departmental annual reports or other reports, papers, etc. (Maps): only folded maps are indexed (Petitions): also indexed by the name of the petitioner and the subject matter (Proclamations): also indexed by subject matter (Reports, Official): at the departmental level only; subject matter is not indexed except for a few unusual cases (Voters Lists): arranged by the electoral district name used at the time the list was compiled. The last voters lists in the Sessional Papers appeared in 1899. Access to all the provincial voters lists held by the BC Archives may also be obtained by consulting a list at the Information Desk in the BC Archives Reference Room. -

Victoria Directory;

F I RST VICTORIA DIRECTORY; COMPRISING A GENERAL DIRECTORY OF CITIZENS, ALSO, ^^l FfticaJ list, it of 1,3Îers, ta! Arrangements AND NOTICES OF TRADES AND PROFESSIONS ; PRECEDED BY A PREFACE and SYNOPSIS of THE COMMERCIAL PROGRESS oF 'rnE • . (^gIunieo of 0xnrouue^ jslund uud Vri#istr ^nluutüiu. ILLUSTRATED. ]-3Y T D W. MALLANDAINE, ABCHITE OT. VICTORIA, V. I. PUBLISHED BY EDW. MALLANDAINE & CO. ......... HÎBBEN & CARSWELL, AND J. F. H+ERRE, AGENTS, VICTORIA, Ÿ. 1. J. J. I,L+'COUNT, BOOKSELLER, AGENT, SAN FRANCISCO, CAL. ......... MA,RCS2 I$GO. 15 ^ Vo ^,^et IMAGE EVALUATION TEST TARGET (MT-3) L: 7•8 2.5 1^ i.e ^ 1.25 L4 1 1111)_ 6" 23 WEST MAIN STREET WEBSTER, N.Y. 14580 (716) S72-4503 CIHM/ICMH CIHM/ICMH Microfiche Collection de Series. microfiches. IJ Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions / Institut canadien de microreproductions historiques Technical and Bibliographic Notes/Notes techniques et bibliographiques The Institute has attempted to obtain the best L'Institut a microfilmé le meilleur exemplaire original copy available for filming. Features of this qu'il lui a été possible de se procurer. Les détails copy which may be bibliographically unique, de cet exemplaire qui sont peut-être uniques du which may alter any of the images in the point de vue bibliographique, qui peuvent modifier reproduction, or which may significantly change une image reproduite, ou qui peuvent exiger une the usual method of filming, are checked below. modification dans la méthode normale de filmage sont indiqués ci-dessous. n Coloured covers/ (^ Coloured pages/ Couverture de couleurI J Pages de couleur ® Covers damaged/ Pages damaged/ Couverture endommagée Z Pages endommagées F-1 Covers restored and/or laminated/ Pages restored and/or laminated/ Couverture restaurée et/ou pelliculée q Pages restaurées et/ou pelliculées FI Cover title missing/ (^ Pages discoloured, stained or foxed/ Le titre de couverture manque LM Pages décolorées, tachetées ou piquées El Coloured maps/ Pages detached/ Cartes géographiques en couleur ® Pages détachées a Coloured ink (i.e. -

British Columbia Terms of Union (1871)

British Columbia Terms of Union (Order of Her Majesty in Council admitting British Columbia into the Union) At the Court at Windsor, the 16th day of May, 1871 PRESENT The QUEEN'S Most Excellent Majesty His Royal Highness Prince ARTHUR Lord Privy Seal Earl Cowper Earl of Kimberley Lord Chamberlain Mr. Secretary Cardwell Mr. Ayrton Whereas by the "Constitution Act, 1867" provision was made for the Union of the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick into the Dominion of Canada, and it was (amongst other things) enacted that it should be lawful for the Queen, by and with the Advice of Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, on Addresses from the Houses of the Parliament of Canada, and of the Legislature of the Colony of British Columbia, to admit that colony into the said Union on such terms and conditions as should be in the Addresses expressed, and as the Queen should think fit to approve, subject to the provisions of the said Act. And it was further enacted that the provisions of any Order in Council in that behalf should have effect as if they had been enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. And whereas by Addresses from the Houses of the Parliament of Canada and from the Legislative Council of British Columbia respectively, of which Addresses copies are contained in the Schedule to this Order annexed, Her Majesty was prayed, by and with the advice of Her most Honourable Privy Council, under the one hundred and fortysixth section of the hereinbefore recited Act, to admit British Columbia into the Dominion of Canada, on the terms and conditions set forth in the said Addresses. -

Benjamin Isitt B.A

Patterns of Protest: Property, Social Movements, and the Law in British Columbia by Benjamin Isitt B.A. (Honours), University of Victoria, 2001 M.A, University of Victoria, 2003 Ph.D. (History), University of New Brunswick, 2008 LL.B., University of London, 2010 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Faculty of Law Benjamin Isitt, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisory Committee Patterns of Protest: Property, Social Movements, and the Law in British Columbia by Benjamin Isitt B.A. (Honours), University of Victoria, 2001 M.A, University of Victoria, 2003 Ph.D. (History), University of New Brunswick, 2008 LL.B., University of London, 2010 Supervisory Committee Dr. Rebecca Johnson, Co-Supervisor University of Victoria Faculty of Law Dr. Eric Tucker, Co-Supervisor Osgoode Hall Law School and University of Victoria Faculty of Graduate Studies Dr. William Carroll, Outside Member University of Victoria Department of Sociology Dr. John McLaren, Additional Member University of Victoria Faculty of Law ii Abstract Embracing a spatial and historical lens and the insights of critical legal theory, this dissertation maps the patterns of protest and the law in modern British Columbia―the social relations of adjudication—the changing ways in which conflict between private property rights and customary rights invoked by social movement actors has been contested and adjudicated in public spaces and legal arenas. From labour strikes in the Vancouver Island coal mines a century ago, to more recent protests by First Nations, environmentalists, pro- and anti-abortion activists, and urban “poor peoples’” movements, social movement actors have asserted customary rights to property through the control or appropriation of space. -

Henry P. Pellew Grease : Confederation Or No Confederation

Henry P. Pellew Grease : Confederation or No Confederation GORDON R. ELLIOTT In 1971 we British Columbians celebrated our fourth centennial in fourteen years. In 1958 we celebrated the establishing of the British Colonies on the west coast of North America; in 1966, the union of those two colonies as British Columbia. It was fairly evident after the Char- lottetown conference in 1864 that the eastern colonies would come together, and in 1967 we celebrated that centennial. As early as March 1867 a new idea had been set to brew on the west coast: the idea was simmering by that summer, bubbling by the next, and at a full rolling boil in 1869. When Henry Pering Pellew Crease, as Attorney-General of British Columbia, opened the debates in the British Columbia Legislative Council on March 9, 1870, he defined the issue as "Confederation or no Confederation."1 In 1971, we celebrated one hundred years as a Canadian province. The view of that Council varied about whether to join Canada or let Canada sink by herself. While Mr. Henry Holbrook, J.P., felt that British Columbia would become the "key-stone of Confederation,"2 Mr. Amor De Cosmos, that strange editorial bird from Victoria District, preferred the expression "corner stone."3 Booming, brash and boastful, John Robson of New Westminster, who believed that until now the progress of the colony had been "like that of the crab — backward,"4 looked to the future: "I believe ... that our agricultural resources may be developed so as to give us one million of population within twenty years, and that this Colony will become of immense importance when the Overland Railway, the true North-West Passage, is established.