Sourcebook on Contract Law, Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burrows 4Th Edn.Indb

Contents Contents Contents Acknowledgements vii Preface ix Table of Cases xxv Table of Legislation li PART ONE: THE FORMATION OF A CONTRACT 1. OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE 3 1. Introduction 3 (1) What is a Contract? 3 (2) Offer and Acceptance 4 2. Offers and Invitations to Treat 4 (1) Two General Illustrative Cases 5 Harvey v Facey 5 Gibson v Manchester City Council 5 (2) Display of Goods for Sale 7 Fisher v Bell 7 Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd 8 (3) Advertisements 10 Partridge v Crittenden 10 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company 11 (4) Auction Sales 15 Barry v Davies 15 (5) Tenders http://www.pbookshop.com 19 Spencer v Harding 19 Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Company of Canada (CI) Ltd 20 Blackpool and Fylde Aeroclub Ltd v Blackpool Borough Council 22 3. Acceptance 25 (1) Acceptance by Conduct 26 Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Co 26 (2) ‘Battle of the Forms’ 27 Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corporation (England) Ltd 27 (3) Communication of Acceptance 33 (a) The General Rule: Acceptance Must Be Received by Offeror 33 Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corporation 33 Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft mbH 35 (b) Acceptance by Post 37 Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Co Ltd v Grant 37 xii Contents Holwell Securities Ltd v Hughes 39 (c) Waiver by Offeror of the Need for Communication of Acceptance 41 Felthouse v Bindley 41 (4) Prescribed Mode of Acceptance 43 Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments Ltd 43 (5) Acceptance in Ignorance of an Offer 45 R v Clarke 45 (6) Acceptance in Unilateral Contracts 47 Errington v Errington 47 Soulsbury v Soulsbury 48 4. -

Misrepresentation

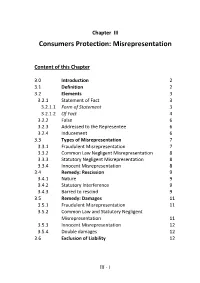

Chapter III Consumers Protection: Misrepresentation Content of this Chapter 3.0 Introduction 2 3.1 Definition 2 3.2 Elements 3 3.2.1 Statement of Fact 3 3.2.1.1 Form of Statement 3 3.2.1.2 Of Fact 4 3.2.2 False 6 3.2.3 Addressed to the Representee 6 3.2.4 Inducement 6 3.3 Types of Misrepresentation 7 3.3.1 Fraudulent Misrepresentation 7 3.3.2 Common Law Negligent Misrepresentation 8 3.3.3 Statutory Negligent Misrepresentation 8 3.3.4 Innocent Misrepresentation 8 3.4 Remedy: Rescission 9 3.4.1 Nature 9 3.4.2 Statutory Interference 9 3.4.3 Barred to rescind 9 3.5 Remedy: Damages 11 3.5.1 Fraudulent Misrepresentation 11 3.5.2 Common Law and Statutory Negligent Misrepresentation 11 3.5.3 Innocent Misrepresentation 12 3.5.4 Double damages 12 3.6 Exclusion of Liability 12 III - 1 3.0 Introduction Misrepresentation is one of the legal grounds reliable for the victim, especially vulnerable consumers, to rescind a contract as well as to claim relief and damages for loss suffered from. The concept of misrepresentation rooted from the common law principal on contract law and later tort. It is important to understand how misrepresentation is constituted at law and each type of misrepresentations. Apart from that, the interference of legislation, i.e. Misrepresentation Ordinance (Cap.284), changed position of remedies in different types of misrepresentation. The legislation also stipulates that the exclusion of liability from misrepresentation shall be subjected to reasonableness. -

The Negotiation Stage

Part I The negotiation stage M02_HALS8786_02_SE_C02.indd 17 7/19/12 3:47 PM M02_HALS8786_02_SE_C02.indd 18 7/19/12 3:47 PM 2 Negotiating the contract Introduction Lord Atkin once remarked that: ‘Businessmen habitually . trust to luck or the good faith of the other party . .’.1 This comment2 provides more than an insight into the motivations of businessmen. It also implicitly acknowledges a limitation of the common law in policing the activities of contractors: the law no more ensures the good faith of your contractual partner than it guarantees your good fortune in business dealings. However, this might not be an accurate description of the purpose of the law relating to pre-contractual negotiations. In an important judgment that was notable for its attempt to place the legal principles under discussion in a broader doctrinal and comparative context Bingham LJ in the Court of Appeal observed that:3 In many civil law systems, and perhaps in most legal systems outside the common law world, the law of obligations recognises and enforces an overriding principle that in making and carrying out contracts parties should act in good faith . It is in essence a principle of fair and open dealing . English law has, characteristically, committed itself to no such overriding principle but has developed piecemeal solutions to demonstrated problems of unfairness. This judgment makes it clear that the gap between civil and common-law jurisdictions is exaggerated by observations at too high a level of generality. While it is true to say that the common law does not explicitly adopt a principle of good faith, it is as obviously untrue to say that the common law encourages bad faith. -

Misrepresentation

5 – MISREPRESENTATION Contract law does not have specific principle requiring disclosure, but there are certain cases where it is needed. Where there is misrepresentation, non-disclosure or mistake, the possible responses are: 1. The contract is void ab initio 2. The contract is voidable via rescission 3. The contract can be rectified to correct the mistake (see previous supervisions) 4. Damages can be awarded to remedy the wrong Where the issue is a statement made in course of negotiations, the remedy will depend on classification of the statement: 1. Contractual term (a ‘warranty’) – damages for breach of contract, possibly termination for breach (depending on nature of term) 2. Misrepresentation – rescission (subject to bars), and potential tort or Misrepresentation Act 1967 damages At one point, misrepresentation could be ground for rescission and damages were available only under the tort of deceit if there was fraud; no damages for innocent misrep. In Hedley Byrne v Heller (1964), HOL made clear breach of the DOC to avoid negligent misstatement could give rise to damages. 1967 Misrepresentation Act extended damages under s 2(1) to the case of misrepresentation inducing a contract where the representor cannot prove absence of negligence or bad faith. This made inference of collateral contract less necessary, although still necessary because representations as to future are harder to fit in scope of Act. Categorising statements made in negotiations Mere puffs These have no legal effect, they mean nothing - Dimmock v Hallett (1866) -

Misrepresentation

Misrepresentation Principle Case (1) A false statement Exception to a false statement: if a true representation is falsified by later events, the With v O’Flanagan [1936] Ch 575 change in circumstances should be communicated Dimmock v Hallett (1866) LR 2 Ch App 21; Implied representations: half-truths lead to Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV actionable misrepresentation [2002] EWCA Civ 15 (2) Existing or past fact An opinion is not usually a statement of fact Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177; and therefore not an actionable Hummingbird Motors v Hobbs [1986] RTR 726 misrepresentation An opinion which is either not held or could not Smith v Land and House Property Corporation be held by a reasonable person with the (1884) 28 Ch D 7 speaker’s knowledge is a statement of fact If there is an unequal skill, knowledge, and Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] 2 All bargaining strength, there is misrepresentation ER 5 An actionable misrepresentation is a false Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch D 459; statement of existing fact (i.e. statement of East v Maurer [1991] 1 WLR 461 intention) Kleinwort Benson v Lincoln CC [1999] 2 AC Misrepresentations of law amount to actionable 349; misrepresentations Pankhania v Hackney LBC [2002] EWHC 2441 (Ch) (3) Made by one party to another If a misrepresentation is made to a third party and, objectively, it is likely that the Cramaso LLP v Ogilvie-Grant [2014] AC 1093 misrepresentation will be passed to the other contracting party, it will be actionable (4) Induces the contract The false statement -

A Casebook on Contract

Contents Preface ix Table of Cases xxv Table of Legislation xlv PART ONE: THE FORMATION OF A CONTRACT 1. OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE 3 1. Introduction 3 (1) What is a Contract? 3 (2) Offer and Acceptance 4 2. Offers and Invitations to Treat 4 (1) Two General Illustrative Cases 5 Harvey v Facey 5 Gibson v Manchester City Council 5 (2) Display of Goods for Sale 7 Fisher v Bell 7 Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd 8 (3) Advertisements 10 Partridge v Crittenden 10 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company 11 (4) Auction Sales 16 Barry v Davies 16 (5) Tenders 19 Spencer v Harding 19 Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Company of Canada (CI) Ltd 20 Blackpool and Fylde Aeroclub Ltd v Blackpool Borough Council 22 3. Acceptance 26 (1) Acceptance by Conduct 26 Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Co 26 (2) 'Battle of the Forms' 27 Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corporation (England) Ltd 27 (3) Communication of Acceptance 33 (a) The General Rule: Acceptance must be Received by Offeror 33 Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corporation 33 Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft mbH 35 (b) Acceptance by Post 37 xii Contents Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Co Ltd v Grant 37 Holwell Securities Ltd v Hughes 39 (c) Waiver by Offeror of the Need for Communication of Acceptance 41 Felt house v Bindley 41 (4) Prescribed Mode of Acceptance 43 Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments Ltd 43 (5) Acceptance in Ignorance of an Offer 45 R v Clarke 45 (6) Acceptance in Unilateral Contracts 47 Errington v Errington 47 4. -

Law for Non-Law Students, Third Edition

LAW FOR NON-LAW STUDENTS Third Edition This book is supported by an online subscription to give you access to periodic updates. To gain access to this area, you need to enter the unique password printed below. The password is protected and your free subscription to the site is valid for 12 months from the date of registration. 1 Go to http://www.cavendishpublishing.com. 2 If you are a registered user of the Cavendish website, log in as usual (with your email address and your personal password). Then click the Law for Non-Law Students button on the home page. You will now see a box next to Law for Non-Law Students. Enter the unique passcode printed below. Once you’ve done that, the word ‘Enter’ appears. Click Enter and that’s where you’ll find your updates. 3 If you are not yet a registered user of the Cavendish website, you will first need to register. Registration is completely free. Click on the ‘Registration’ button at the top of your screen, then type in your email address and a password. You should use something personal and memorable to you. Then click the Law for Non-Law Students button on the home page. You will now see a box next to Law for Non-Law Students. Enter the unique passcode printed below. Once you’ve done that, the word ‘Enter’ appears. Click Enter and that’s where you’ll find your updates 4 Cavendish will email you each time updates are uploaded. All you need to do to obtain any past or future updates is to go to http:// www.cavendishpublishing.com and follow the instructions in point 2 above. -

Breach of Information Duties in the B2C E-Commerce: a Comparative Analysis of English and Spanish Law

Breach of Information Duties in the B2C E-Commerce: A Comparative Analysis of English and Spanish Law Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Law at the University of M´alaga, Spain, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zofia Bednarz Departamento de Derecho Privado Especial Area´ de Derecho Mercantil Supervised by Dr Juan Ignacio Peinado Gracia and Dra Patricia M´arquezLobillo June 2017 AUTOR: Zofia Bednarz http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6719-8101 EDITA: Publicaciones y Divulgación Científica. Universidad de Málaga Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial- SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cualquier parte de esta obra se puede reproducir sin autorización pero con el reconocimiento y atribución de los autores. No se puede hacer uso comercial de la obra y no se puede alterar, transformar o hacer obras derivadas. Esta Tesis Doctoral está depositada en el Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad de Málaga (RIUMA): riuma.uma.es Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) iii Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors Dr. Juan Ignacio Peinado Gracia and Dra. Patricia M´arquezLobillo, for the continuous support of my Ph.D study and related research, for their patience, motivation, and help in navigating through the difficult process. Besides my supervisors, I would like to thank the external reviewers of my dissertation: Dr. Raffaele Lener and Dr. Christian Twigg-Flesner, for their insightful comments, which contributed to improving the study presented here. My sincere thanks also goes to Dr. Paula Giliker, who provided me with an opportunity to make a research stay at the University of Bristol, without which this study would not have been possible. -

Formation: Offer and Acceptance

Formation: Offer and Acceptance How do we know if a contract exists? Þ Offer and acceptance Þ Consideration Þ Intention to be legally bound Þ Certainty of the contract and its terms Þ Some contracts need to be in a certain form Þ Capacity to enter into contract, e.g. a young person cannot enter into a contract Offer: Intention to contract is unequivocal. Agreement: a consensus (meeting of the minds) amongst all parties aBout the arrangement. There must Be objective evidence of the agreement à Not suBjective, there is no agreement if you don’t say or indicate clear agreement/undertaking. Making a commitment: There is an immediate readiness to Be Bound/undertake obligation/assume responsiBility à e.g. language showing commitment or conduct ----- Invitation to Treat (Invitation to Make Offers) Harvey v Facey [1893] Provision of information, not an offer. Fisher v Bell [1961] Shop window invites offers But is not an offer itself. Only providing an example of things they sell, could Be out of stock which is unfair on the shop. A shop is a place of Bargaining, not of definite sales, and you can haggle about the price (outdated in modern conditions). ‘Snapping-up’ cases Ex. Online shopping at Argos The price + description of a TV set is put on the weBsite £2.99. Customer Bought 200 units, and Argos confirmed payment + delivery. Q: Is the weBsite the same as the shop window? ‘Add to Basket’ = offer, payment confirmation = acceptance One party knows/should have known aBout the other’s mistake. In selling, the customer makes the offer. -

Burrows-3Rd Edn.Vp

Contents Acknowledgements vii Preface ix Table of Cases xxv Table of Legislation xlix PART ONE: THE FORMATION OF A CONTRACT 1. OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE 3 1. Introduction 3 (1) What is a Contract? 3 (2) Offer and Acceptance 4 2. Offers and Invitations to Treat 4 (1) Two General Illustrative Cases 5 Harvey v Facey 5 Gibson v Manchester City Council 5 (2) Display of Goods for Sale 7 Fisher v Bell 7 Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd 8 (3) Advertisements 10 Partridge v Crittenden 10 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company 11 (4) Auction Sales http://www.pbookshop.com 16 Barry v Davies 16 (5) Tenders 19 Spencer v Harding 19 Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Company of Canada (CI) Ltd 20 Blackpool and Fylde Aeroclub Ltd v Blackpool Borough Council 22 3. Acceptance 26 (1) Acceptance by Conduct 26 Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Co 26 (2) ‘Battle of the Forms’ 27 Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corporation (England) Ltd 27 (3) Communication of Acceptance 33 (a) The General Rule: Acceptance must be Received by Offeror 33 Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corporation 33 Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft mbH 36 xii Contents (b) Acceptance by Post 38 Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Co Ltd v Grant 38 Holwell Securities Ltd v Hughes 40 (c) Waiver by Offeror of the Need for Communication of Acceptance 42 Felthouse v Bindley 42 (4) Prescribed Mode of Acceptance 44 Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments Ltd 44 (5) Acceptance in Ignorance of an Offer 45 R v Clarke 45 (6) Acceptance in Unilateral Contracts 48 Errington v Errington 48 Soulsbury v Soulsbury 49 4. -

Misrepresentation

Vitiating Factors: Misrepresentation Fraud à a form of misrepresentation Misrepresentation: One party enters into a contract on the basis of something that another party has told them, and this is not in fact true. From the outset, distinguish between misrepresentation (false statement of fact/law that induces a contract) and contractual term. Difference between misrepresentation and warranty (a contractual term): Warranty a. A term in the contract between the parties b. A separate contract between the parties Leading decision on difference between representations and warranties: Heilbut, Symons & Co v Buckleton [1913] If you give a contractual promise a warranty, whether it is a term of an existing contract or forms the basis of a separate contract, and it is in fact not good, then the contract is broken and you can seek damages. If however, the statement is merely a representation, if it’s not true you don’t get damages for breach of contract. At most you can establish that the representation is actionable as a misrepresentation. Lord Moulton on warranties: “animus contrahendi (intention to contract)” Þ Importance of the statement, the more important the statement the more likely for it to be a contractual form. Þ Reliance put on this statement by the parties. Þ Relative knowledge of the two parties, where a more experience + knowledgeable party makes a statement that he knows the other is relying upon, it is more likely for this to be a contractual term. Oscar Chess Ltd v Williams [1957] Lord Denning: How you determine whether something is a warranty or a representation is done on an objective basis, doesn’t look into the minds of the parties but decides whether or not it would appear that they intended the statement to be a warranty.