Law for Non-Law Students, Third Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Partridge V Crittenden [1968] 1 WLR 1204 - 04-25-2019 by Travis - Law Case Summaries](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4092/partridge-v-crittenden-1968-1-wlr-1204-04-25-2019-by-travis-law-case-summaries-14092.webp)

Partridge V Crittenden [1968] 1 WLR 1204 - 04-25-2019 by Travis - Law Case Summaries

Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 1 WLR 1204 - 04-25-2019 by Travis - Law Case Summaries - https://lawcasesummaries.com Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 1 WLR 1204 https://lawcasesummaries.com/knowledge-base/partridge-v-crittenden-1968-1-wlr-1204/ Facts On 13 April 1967, an advertisement by Arthur Partridge appeared in a periodical called "Cage and Aviary Birds". The advertisement stated: "Quality British A.B.C.R... Bramblefinch cocks, Bramblefinch hens 25 s. each." The advertisement made no mention of any "offer for sale". Partridge sold one of these birds to Thomas Thompson, who had sent a cheque to Partridge with the required purchase amount enclosed. Anthony Crittenden, a member of the RSPCA, charged Partridge for selling a live wild bird in violation of section 6 of the Protection of Birds Act 1954 (UK). The magistrate decided that the advertisement was an offer for sale and Partridge was convicted. Partridge appealed. Issues Did the advertisement constitute an offer for sale or merely an invitation to treat? Held The UK High Court held that the advertisement was an invitation to treat. The advertisement had appeared in the "Classified Advertisements" section of the periodical. It made no mention of being an "offer for sale". The Court considered Fisher v Bell, where a shopkeeper had advertised a prohibited weapon in his shop front window with a price tag. In that case, it was plain the placement of the weapon with a price tag constituted an offer for sale. However, in this situation, the advertisement was merely an invitation to treat, given its placement in the periodical. -

Offer and Acceptance

CHAPTER TWO Offer and Acceptance [2:01] In determining whether parties have reached an agreement, the courts have adopted an intellectual framework that analyses transactions in terms of offer and acceptance. For an agreement to have been formed, therefore, it is necessary to show that one party to the transaction has made an offer, which has been accepted by the other party: the offer and acceptance together make up an agreement. The person who makes the offer is known as the offeror; the person to whom the offer is made is known as the offeree. [2:02] It is important not to be taken in by the deceptive familiarity of the words “offer” and “acceptance”. While these are straightforward English words, in the contract context they have acquired additional layers of meaning. The essential elements of a valid offer are: (a) The terms of the offer must be clear, certain and complete; (b) The offer must be communicated to the other party; (c) The offer must be made by written or spoken words, or be inferred by the conduct of the parties; (d) The offer must be intended as such before a contract can arise. What is an offer? Clark gives this definition: “An offer may be defined as a clear and unambiguous statement of the terms upon which the offeror is willing to contract, should the person or persons to whom the offer is directed decide to accept.”1 An further definition arises in the case of Storer v Manchester City Council [1974] 2 All ER 824, the court stated that an offer “…empowers persons to whom it is addressed to create contract by their acceptance.” [2:03] The first point to be noted from Clark’s succinct definition is that an offer must be something that will be converted into a contract once accepted. -

Important Concepts in Contract

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Practical concepts in Contract Law Ehsan, zarrokh 14 August 2008 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10077/ MPRA Paper No. 10077, posted 01 Jan 2009 09:21 UTC Practical concepts in Contract Law Author: EHSAN ZARROKH LL.M at university of Tehran E-mail: [email protected] TEL: 00989183395983 URL: http://www.zarrokh2007.20m.com Abstract A contract is a legally binding exchange of promises or agreement between parties that the law will enforce. Contract law is based on the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda (literally, promises must be kept) [1]. Breach of a contract is recognised by the law and remedies can be provided. Almost everyone makes contracts everyday. Sometimes written contracts are required, e.g., when buying a house [2]. However the vast majority of contracts can be and are made orally, like buying a law text book, or a coffee at a shop. Contract law can be classified, as is habitual in civil law systems, as part of a general law of obligations (along with tort, unjust enrichment or restitution). Contractual formation Keywords: contract, important concepts, legal analyse, comparative. The Carbolic Smoke Ball offer, which bankrupted the Co. because it could not fulfill the terms it advertised In common law jurisdictions there are three key elements to the creation of a contract. These are offer and acceptance, consideration and an intention to create legal relations. In civil law systems the concept of consideration is not central. In addition, for some contracts formalities must be complied with under what is sometimes called a statute of frauds. -

Invitation to Treat Cases Pdf

Invitation to treat cases pdf Continue 2012/// Filed in: Treaty Law (UK)Below are the most relevant principles and leading cases concerning proposals against other steps in the negotiation process:Storer v Manchester City Council: The proposal is an expression of readiness to enter into a contract on certain terms after adoption. Gibson v Manchester City Council: Talks about entering into a contract of invitations for treatment, but does not offer Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co: Advertising for one-way contracts can make up proposals, even if addressed to the general public, if the advertisement objectively person making the advertisement intends to be linked by it. Partridge v Crittenden: Advertising in print for goods at a certain price is generally considered an invitation for treatment and are not offers. Fisher v Bell: Items with a price brand on shelves or on windows or in stores are generally considered invitations for treatment and are not offers. Pharmaceutical Society GB v Boots Cash Chemists: Self-service-based items are invitations for treatment, the customer makes an offer to buy at the box office. Walford v Miles: Negotiation agreements are invitations for treatment and are not a binding contract, instead they are considered as pre-contract negotiations. Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Co of Canada Ltd: As a rule, tenders are invitations for treatment unless clear language for acceptance of the proposal (e.g. Harvela). Blackpool Fylde Areo Club v Blackpool Borough Council: Invitations to tender include an implicit offer to consider all tenders properly submitted, but not necessarily accepting one. -

Misrepresentation

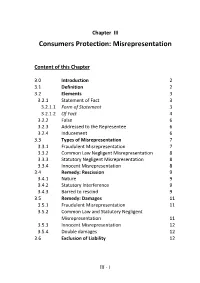

Chapter III Consumers Protection: Misrepresentation Content of this Chapter 3.0 Introduction 2 3.1 Definition 2 3.2 Elements 3 3.2.1 Statement of Fact 3 3.2.1.1 Form of Statement 3 3.2.1.2 Of Fact 4 3.2.2 False 6 3.2.3 Addressed to the Representee 6 3.2.4 Inducement 6 3.3 Types of Misrepresentation 7 3.3.1 Fraudulent Misrepresentation 7 3.3.2 Common Law Negligent Misrepresentation 8 3.3.3 Statutory Negligent Misrepresentation 8 3.3.4 Innocent Misrepresentation 8 3.4 Remedy: Rescission 9 3.4.1 Nature 9 3.4.2 Statutory Interference 9 3.4.3 Barred to rescind 9 3.5 Remedy: Damages 11 3.5.1 Fraudulent Misrepresentation 11 3.5.2 Common Law and Statutory Negligent Misrepresentation 11 3.5.3 Innocent Misrepresentation 12 3.5.4 Double damages 12 3.6 Exclusion of Liability 12 III - 1 3.0 Introduction Misrepresentation is one of the legal grounds reliable for the victim, especially vulnerable consumers, to rescind a contract as well as to claim relief and damages for loss suffered from. The concept of misrepresentation rooted from the common law principal on contract law and later tort. It is important to understand how misrepresentation is constituted at law and each type of misrepresentations. Apart from that, the interference of legislation, i.e. Misrepresentation Ordinance (Cap.284), changed position of remedies in different types of misrepresentation. The legislation also stipulates that the exclusion of liability from misrepresentation shall be subjected to reasonableness. -

The Negotiation Stage

Part I The negotiation stage M02_HALS8786_02_SE_C02.indd 17 7/19/12 3:47 PM M02_HALS8786_02_SE_C02.indd 18 7/19/12 3:47 PM 2 Negotiating the contract Introduction Lord Atkin once remarked that: ‘Businessmen habitually . trust to luck or the good faith of the other party . .’.1 This comment2 provides more than an insight into the motivations of businessmen. It also implicitly acknowledges a limitation of the common law in policing the activities of contractors: the law no more ensures the good faith of your contractual partner than it guarantees your good fortune in business dealings. However, this might not be an accurate description of the purpose of the law relating to pre-contractual negotiations. In an important judgment that was notable for its attempt to place the legal principles under discussion in a broader doctrinal and comparative context Bingham LJ in the Court of Appeal observed that:3 In many civil law systems, and perhaps in most legal systems outside the common law world, the law of obligations recognises and enforces an overriding principle that in making and carrying out contracts parties should act in good faith . It is in essence a principle of fair and open dealing . English law has, characteristically, committed itself to no such overriding principle but has developed piecemeal solutions to demonstrated problems of unfairness. This judgment makes it clear that the gap between civil and common-law jurisdictions is exaggerated by observations at too high a level of generality. While it is true to say that the common law does not explicitly adopt a principle of good faith, it is as obviously untrue to say that the common law encourages bad faith. -

Contract Law

Contract Law Formation of a Contract To start with it needs to be identified whether and which party is alleging a contract. For a contract to be valid it must be: 1.! An agreement 2.! Contractual intention 3.! Consideration Agreement An agreement is formed if there is a valid offer and an acceptance. There must be certainty in the offer and acceptance otherwise the court would not uphold the contract (Scammell v Ousten). →! Hillas v Arcas – the use of ‘timber of fair specification’ was not too vague to form a contract as the parties had dealt with each other before and were well acquainted with the timber industry Offer An offer is “an expression or willingness to contract on certain terms, made with the intention that it shall become binding as soon as it is accepted by the person to whom it is addressed” (Trietel 13th Ed; confirmed in Allied Marine Transport). This will be assessed objectively (Smith v Hughes) This is distinguished from an invitation to treat (ITT), which is where one party merely invites offers from another party and which he is then free to accept or reject. →! Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball – Was considered an offer not ITT even though it had aspects if an ITT. This was because the defendant had taken actions (depositing £1,000) to indicate that it took the promise seriously, thus it was an offer to anyone who satisfied the conditions, even if they didn’t communicate acceptance as it waived the requirement Case Law: →! Fisher v Bell – Generally speaking goods on display and advertisements in newspapers or periodicals that the advertiser has goods for sale are not offers 1 Contract Law →! Partridge v Crittenden – advertisements are generally an ITT →! Grainger v Gough – Similarly catalogues or price lists are also ITT. -

Basic Principles of English Contract Law

ADVOCATES FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AT A GLANCE GUIDE TO BASIC PRINCIPLES OF ENGLISH CONTRACT LAW Prepared by lawyers from www.a4id.org TABLE OF CONTENTS I FORMATION OF A CONTRACT A. OFFER B. ACCEPTANCE C. CONSIDERATION D. CONTRACTUAL INTENTION E. FORM II CONTENTS OF A CONTRACT A. EXPRESS TERMS B. IMPLIED TERMS III THE END OF A CONTRACT – EXPIRATION, TERMINATION, VITIATION, FRUSTRATION A EXPIRATION B TERMINATION C VITIATION D FRUSTRATION VI DAMAGES / REMEDIES BASIC PRINCIPLES OF ENGLISH CONTRACT LAW INTRODUCTION This Guide is arranged in the following parts: I Formation of a Contract II Contents of a Contract III The end of a Contract I FORMATION OF A CONTRACT 1. A contract is an agreement giving rise to obligations which are enforced or recognised by law. 2. In common law, there are 3 basic essentials to the creation of a contract: (i) agreement; (ii) contractual intention; and (iii) consideration. 3. The first requisite of a contract is that the parties should have reached agreement. Generally speaking, an agreement is reached when one party makes an offer, which is accepted by another party. In deciding whether the parties have reached agreement, the courts will apply an objective test. A. OFFER 4. An offer is an expression of willingness to contract on specified terms, made with the intention that it is to be binding once accepted by the person to whom it is addressed.1 There must be an objective manifestation of intent by the offeror to be bound by the offer if accepted by the other party. Therefore, the offeror will be bound if his words or conduct are such as to induce a reasonable third party observer to believe that he intends to be bound, even if in fact he has no such intention. -

Misrepresentation

5 – MISREPRESENTATION Contract law does not have specific principle requiring disclosure, but there are certain cases where it is needed. Where there is misrepresentation, non-disclosure or mistake, the possible responses are: 1. The contract is void ab initio 2. The contract is voidable via rescission 3. The contract can be rectified to correct the mistake (see previous supervisions) 4. Damages can be awarded to remedy the wrong Where the issue is a statement made in course of negotiations, the remedy will depend on classification of the statement: 1. Contractual term (a ‘warranty’) – damages for breach of contract, possibly termination for breach (depending on nature of term) 2. Misrepresentation – rescission (subject to bars), and potential tort or Misrepresentation Act 1967 damages At one point, misrepresentation could be ground for rescission and damages were available only under the tort of deceit if there was fraud; no damages for innocent misrep. In Hedley Byrne v Heller (1964), HOL made clear breach of the DOC to avoid negligent misstatement could give rise to damages. 1967 Misrepresentation Act extended damages under s 2(1) to the case of misrepresentation inducing a contract where the representor cannot prove absence of negligence or bad faith. This made inference of collateral contract less necessary, although still necessary because representations as to future are harder to fit in scope of Act. Categorising statements made in negotiations Mere puffs These have no legal effect, they mean nothing - Dimmock v Hallett (1866) -

De Montfort Law School Schools and Colleges Mooting Competition 2016

De Montfort Law School Schools and Colleges Mooting Competition 2016 Vm/lawclub/mootinghandbook12 1 vm/lawclub/mootinghandbook12 2 CONTENTS Introduction 2 Programme 3 Mooting Instructions 4 Contract books and looking up cases 7 Round One Moot 9 Round Two Moot 10 Moot Final 11 Background Notes on Formation of Contract 12 vm/lawclub/mootinghandbook12 3 INTRODUCTION Welcome! The De Montfort Schools and Colleges Mooting Competition is now in its thirteenth year. We hope you find participating in moots an enjoyable and rewarding experience. If you do go on to study law at university, we trust that you will have found it useful to have had a first shot at it before starting on your degree course. Most university law schools run student mooting competitions and also enter teams for national competitions. All the moots in our competition are designed for students who have not studied A-level law. We have included a set of background notes on the law of contract formation (offer and acceptance). Traditionally a contract is formed when an offer has been accepted. All the moots depend on arguing whether a valid offer has (or has not) been made and whether acceptance has (or has not) taken place. If you need to contact the Law School the telephone number is 257 7177 and you can e-mail on [email protected] Andy Robinson Law Club Organiser vm/lawclub/mootinghandbook12 4 PROGRAMME Tuesday 19 January 2016 Andy Robinson will explain how the mooting competition is organised, followed by a demonstration moot by two De Montfort University students. -

Introduction Offer

INTRODUCTION A contract may be defined as an agreement between two or more parties that is intended to be legally binding. The first requisite of any contract is an agreement (consisting of an offer and acceptance). At least two parties are required; one of them, the offeror, makes an offer which the other, the offeree, accepts. OFFER An offer is an expression of willingness to contract made with the intention that it shall become binding on the offeror as soon as it is accepted by the offeree. A genuine offer is different from what is known as an "invitation to treat", ie where a party is merely inviting offers, which he is then free to accept or reject. The following are examples of invitations to treat: 1. AUCTIONS In an auction, the auctioneer's call for bids is an invitation to treat, a request for offers. The bids made by persons at the auction are offers, which the auctioneer can accept or reject as he chooses. Similarly, the bidder may retract his bid before it is accepted. See: Payne v Cave (1789) 3 Term Rep 148 2. DISPLAY OF GOODS The display of goods with a price ticket attached in a shop window or on a supermarket shelf is not an offer to sell but an invitation for customers to make an offer to buy. See: Fisher v Bell [1960] 3 All ER 731 P.S.G.B. v Boots Chemists [1953] 1 All ER 482. 3. ADVERTISEMENTS Advertisements of goods for sale are normally interpreted as invitations to treat. -

Misrepresentation

Misrepresentation Principle Case (1) A false statement Exception to a false statement: if a true representation is falsified by later events, the With v O’Flanagan [1936] Ch 575 change in circumstances should be communicated Dimmock v Hallett (1866) LR 2 Ch App 21; Implied representations: half-truths lead to Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV actionable misrepresentation [2002] EWCA Civ 15 (2) Existing or past fact An opinion is not usually a statement of fact Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177; and therefore not an actionable Hummingbird Motors v Hobbs [1986] RTR 726 misrepresentation An opinion which is either not held or could not Smith v Land and House Property Corporation be held by a reasonable person with the (1884) 28 Ch D 7 speaker’s knowledge is a statement of fact If there is an unequal skill, knowledge, and Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] 2 All bargaining strength, there is misrepresentation ER 5 An actionable misrepresentation is a false Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch D 459; statement of existing fact (i.e. statement of East v Maurer [1991] 1 WLR 461 intention) Kleinwort Benson v Lincoln CC [1999] 2 AC Misrepresentations of law amount to actionable 349; misrepresentations Pankhania v Hackney LBC [2002] EWHC 2441 (Ch) (3) Made by one party to another If a misrepresentation is made to a third party and, objectively, it is likely that the Cramaso LLP v Ogilvie-Grant [2014] AC 1093 misrepresentation will be passed to the other contracting party, it will be actionable (4) Induces the contract The false statement