Misrepresentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implied Terms: the Foundation in Good Faith and Fair Dealing LSE Research Online URL for This Paper: Version: Accepted Version

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Implied terms: the foundation in good faith and fair dealing LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101641/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Collins, Hugh (2014) Implied terms: the foundation in good faith and fair dealing. Current Legal Problems, 67 (1). 297 - 331. ISSN 0070-1998 https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/cuu002 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ Implied Terms: the Foundation in Good Faith and Fair Dealing Hugh Collins* Confusion as much as controversy permeates the subject of implied terms in contracts. Controversy always surrounds their purpose and legitimacy, for implied terms lie on the point of friction between the basic disposition of the common law to respect freedom of contract and the regulatory impulse to prevent the worst instances of market exploitation and opportunism. Implied terms permit judicial intervention whilst maintaining the appearance of conformity to the idea of respecting the parties’ self-determination. Confusion now reigns as well, however, for there is no consensus on the legal tests for the introduction of implied terms into contracts, even to the extent of losing them altogether within the nebula of the interpretation of contracts. -

THE MODERN LAW of CONTRACT, Eighth Edition

The Modern Law of Contract Eighth Edition Written by a leading author and lecturer with over thirty years’ experience teaching and examining contract law, The Modern Law of Contract continues to equip students with a clear and logical introduction to contract law. Exploring all of the recent developments and case decisions in the field of contract law, it combines a meticulous examination of authorities and commentar- ies with a modern contextual approach. An ideal accessible introduction to con- tract law for students coming to legal study for the first time, this leading textbook offers straightforward explanations of all of the topics found on an undergraduate or GDL contract law module. At the same time, coverage of a variety of theoretical approaches: economic, sociological and empirical encourages reflective thought and critical analysis. New features include: boxed chapter summaries, which help to consolidate learning and understanding; additional ‘For thought’ think points throughout the text where students are asked to consider ‘what if’ scenarios; new diagrams to illustrate principles and facilitate the understanding of concepts and interrelationships; new Key Case close-ups designed to help students identify key cases within contract law and improve their understanding of the facts and context of each case; a Companion Website with half-yearly updates; chapter-by-chapter Multiple Choice Questions; a Flashcard glossary; contract law skills advice; PowerPoint slides of the diagrams within the book; and sample essay questions; new, attractive two-colour text design to improve presentation and help consolidate learning. Clearly written and easy to use, this book enables undergraduate students of contract law to fully engage with the topic and gain a profound understanding of this pivotal area. -

Business Law, Fifth Edition

BUSINESS LAW Fifth Edition This book is supported by a Companion Website, created to keep Business Law up to date and to provide enhanced resources for both students and lecturers. Key features include: ◆ termly updates ◆ links to useful websites ◆ links to ‘ebooks’ for introductory and further reading ◆ ‘ask the author’ – your questions answered www.cavendishpublishing.com/businesslaw BUSINESS LAW Fifth Edition David Kelly, PhD Principal Lecturer in Law Staffordshire University Ann Holmes, M Phil, PGD Dean of the Law School Staffordshire University Ruth Hayward, LLB, LLM Senior Lecturer in Law Staffordshire University Fifth edition first published in Great Britain 2005 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom Telephone: + 44 (0)20 7278 8000 Facsimile: + 44 (0)20 7278 8080 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cavendishpublishing.com Published in the United States by Cavendish Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services, 5804 NE Hassalo Street, Portland, Oregon 97213-3644, USA Published in Australia by Cavendish Publishing (Australia) Pty Ltd 3/303 Barrenjoey Road, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia Email: [email protected] Website: www.cavendishpublishing.com.au © Kelly, D, Holmes, A and Hayward, R 2005 First edition 1995 Second edition 1997 Third edition 2000 Fourth edition 2002 Fifth edition 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Cavendish Publishing Limited, or as expressly permitted by law, or under the terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Contents of a Contract Representations and Misrepresentations

THE LAW OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND CARRIAGE OF GOODS CONTENTS OF A CONTRACT REPRESENTATIONS AND MISREPRESENTATIONS. General definition : A representation is a statement about a factual situation, current or historical, or about a person’s state of mind, including an opinion or belief. Examples include a statement about the condition of a ship or its location, opinions or beliefs about the condition or location of the ship, statements about the vessel’s ability to perform a particular task and statements about where the ship has been or what it has done. A misrepresentation is a false representation. Distinctions : It is important to distinguish representations made as part of negotiations or otherwise, which give rise to remedies in their own right from other statements (or representations) which give rise to actions in other areas of contract. The above must also be distinguished from statements which are of no legal significance whatsoever. A statement may :- a) be a representation which gives rise to remedies discussed in this section; or b) become incorporated as a term of a contract1 for example s12-15 SOGA 1979 ; or c) form the basis of a collateral contract Esso Petroleum v Marsden 2 : Shanklin Pier v Detol Products 3; City of Westminster Properties v Mudd 4 or d) be a mere tradesmanʹs puff as alleged in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co.5 which gives rise to no rights whatsoever since no one relies on them or expects them to be true. e) be a throw away remark, made in jest or casual conversation, with no expectation that anyone might take it seriously or rely upon it. -

(A) Forte Prelims

GOOD FAITH IN CONTRACT AND PROPERTY GOOD FAITH IN CONTRACT AND PROPERTY Edited by A. D. M. Forte OXFORD – PORTLAND OREGON 1999 Hart Publishing Oxford and Portland, Oregon Published in North America (US and Canada) by Hart Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services 5804 NE Hassalo Street Portland, Oregon 97213-3644 USA Distributed in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg by Intersentia, Churchillaan 108 B2900 Schoten Antwerpen Belgium Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Federation Press John St Leichhardt NSW 2000 © The contributors severally 1999 The contributors have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work Hart Publishing Ltd is a specialist legal publisher based in Oxford, England. To order further copies of this book or to request a list of other publications please write to: Hart Publishing Ltd, Salter’s Boatyard, Oxford OX1 4LB Telephone: +44 (0)1865 245533 or Fax: +44 (0)1865 794882 e-mail: [email protected] British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data Available ISBN 1 84113–047–8 Typeset by Hope Services (Abingdon) Ltd. Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and Kings Lynn. CONTENTS Table of Cases xi Table of Legislation and Delegated Legislation xix Table of International Conventions and Principles xxiii Preface The Right Honourable the Lord Rodger of Earlsferry, Lord President xiv 1. Introduction 1 A.D.M. Forte 2. Good Faith in the Scots Law of Contract: An Undisclosed Principle? 5 Hector L. MacQueen 3. Good Faith: A Matter of Principle? 39 Ewan McKendrick 4. -

Misrepresentation

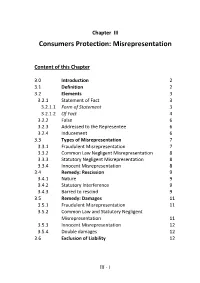

Chapter III Consumers Protection: Misrepresentation Content of this Chapter 3.0 Introduction 2 3.1 Definition 2 3.2 Elements 3 3.2.1 Statement of Fact 3 3.2.1.1 Form of Statement 3 3.2.1.2 Of Fact 4 3.2.2 False 6 3.2.3 Addressed to the Representee 6 3.2.4 Inducement 6 3.3 Types of Misrepresentation 7 3.3.1 Fraudulent Misrepresentation 7 3.3.2 Common Law Negligent Misrepresentation 8 3.3.3 Statutory Negligent Misrepresentation 8 3.3.4 Innocent Misrepresentation 8 3.4 Remedy: Rescission 9 3.4.1 Nature 9 3.4.2 Statutory Interference 9 3.4.3 Barred to rescind 9 3.5 Remedy: Damages 11 3.5.1 Fraudulent Misrepresentation 11 3.5.2 Common Law and Statutory Negligent Misrepresentation 11 3.5.3 Innocent Misrepresentation 12 3.5.4 Double damages 12 3.6 Exclusion of Liability 12 III - 1 3.0 Introduction Misrepresentation is one of the legal grounds reliable for the victim, especially vulnerable consumers, to rescind a contract as well as to claim relief and damages for loss suffered from. The concept of misrepresentation rooted from the common law principal on contract law and later tort. It is important to understand how misrepresentation is constituted at law and each type of misrepresentations. Apart from that, the interference of legislation, i.e. Misrepresentation Ordinance (Cap.284), changed position of remedies in different types of misrepresentation. The legislation also stipulates that the exclusion of liability from misrepresentation shall be subjected to reasonableness. -

The Negotiation Stage

Part I The negotiation stage M02_HALS8786_02_SE_C02.indd 17 7/19/12 3:47 PM M02_HALS8786_02_SE_C02.indd 18 7/19/12 3:47 PM 2 Negotiating the contract Introduction Lord Atkin once remarked that: ‘Businessmen habitually . trust to luck or the good faith of the other party . .’.1 This comment2 provides more than an insight into the motivations of businessmen. It also implicitly acknowledges a limitation of the common law in policing the activities of contractors: the law no more ensures the good faith of your contractual partner than it guarantees your good fortune in business dealings. However, this might not be an accurate description of the purpose of the law relating to pre-contractual negotiations. In an important judgment that was notable for its attempt to place the legal principles under discussion in a broader doctrinal and comparative context Bingham LJ in the Court of Appeal observed that:3 In many civil law systems, and perhaps in most legal systems outside the common law world, the law of obligations recognises and enforces an overriding principle that in making and carrying out contracts parties should act in good faith . It is in essence a principle of fair and open dealing . English law has, characteristically, committed itself to no such overriding principle but has developed piecemeal solutions to demonstrated problems of unfairness. This judgment makes it clear that the gap between civil and common-law jurisdictions is exaggerated by observations at too high a level of generality. While it is true to say that the common law does not explicitly adopt a principle of good faith, it is as obviously untrue to say that the common law encourages bad faith. -

Xxxi BIBLIOGRAPHY a Alton WG Malpractise

BIBLIOGRAPHY A Alton W.G. Malpractise (1977) American College Legal Dynamics of Medical Encounters Legal Medicine (1991) Amundsen D.W. "The Liability of the Physician in Roman Law" International Symposium on Society, Medicine And Law (edited by Karplus) (1973) 17 Aronstam P. Freedom of Contract, Consumer Protection and the Law (1979) Aronstam P. "Unconscionable Contracts the South African Solution?" 1979 42 THRHR 18 Arterburn N.F. "The Origin and First Test of Public Callings" University Of Pennsylvania Law Review Vol. 75 (1927) 4111 Atiyah P.S. An Introduction to the Law of Contract 2d ed. (1995) Atiyah P.S. The Rise and fall of Freedom of Contract (1979) B Beale K. "Unfair Contract terms Act 1977" British Journal of Law And Society Vol. 5 No 1 (1978) 114 at 115 Beatson J. Anson's Law of Contract (2002) Beatson J. and Friedman D. Good Faith and Fault in Contractual Law (1995) Benatar S.R. "The changing doctor-patient relationship and the new medical ethics" SA Journal of Continuing Medical Education Vol. 5 April (1987) Berkhouwer C. and Vorstman L.D. De Aansprakelijkheid van de Medicus voor Beroepsfouten door Hem en Zijn Helpers Gemaakt (1950) Bertolet M.M. and Goldsmith L.S. Hospital Liability Law and Practice (1987) Beauchamp T.L. and Childress J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics (1994) Bhana N. and Pieterse J.M. "Towards a reconciliation of contract law and Constitutional values: Brisley and Afrox Revised 2005 123 SALJ 865 Bianco E.A. and Hirsh H.L. "Consent to and refusal of medical treatment" Published in American College of Legal Medicine - Legal Medicine (1991) Bisbin S.B. -

Misrepresentation

Misrepresentation Principle Case (1) A false statement Exception to a false statement: if a true representation is falsified by later events, the With v O’Flanagan [1936] Ch 575 change in circumstances should be communicated Dimmock v Hallett (1866) LR 2 Ch App 21; Implied representations: half-truths lead to Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV actionable misrepresentation [2002] EWCA Civ 15 (2) Existing or past fact An opinion is not usually a statement of fact Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177; and therefore not an actionable Hummingbird Motors v Hobbs [1986] RTR 726 misrepresentation An opinion which is either not held or could not Smith v Land and House Property Corporation be held by a reasonable person with the (1884) 28 Ch D 7 speaker’s knowledge is a statement of fact If there is an unequal skill, knowledge, and Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] 2 All bargaining strength, there is misrepresentation ER 5 An actionable misrepresentation is a false Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch D 459; statement of existing fact (i.e. statement of East v Maurer [1991] 1 WLR 461 intention) Kleinwort Benson v Lincoln CC [1999] 2 AC Misrepresentations of law amount to actionable 349; misrepresentations Pankhania v Hackney LBC [2002] EWHC 2441 (Ch) (3) Made by one party to another If a misrepresentation is made to a third party and, objectively, it is likely that the Cramaso LLP v Ogilvie-Grant [2014] AC 1093 misrepresentation will be passed to the other contracting party, it will be actionable (4) Induces the contract The false statement -

The Basis of Contractual Duties of Good Faith

Paul Davis Printer's Version 2.0 (Do Not Delete) 5/25/2019 12:31 PM THE BASIS OF CONTRACTUAL DUTIES OF GOOD FAITH PAUL S DAVIES* ABSTRACT. This article considers the basis of duties of good faith where not expressly provided for by the parties. It analyses the different approaches adopted in Canada and England and Wales, and assesses whether good faith is part of an ‘irreducible core’ of contract law or whether it should only be introduced into a contract through the mechanism of implied terms. It is suggested that the latter approach is preferable, and that (in the commercial context at least) courts should be wary about imposing duties of good faith on parties who did not provide for such duties. Well-advised commercial parties who wish particular duties to govern their relationship should be encouraged to stipulate such duties expressly in their contract. KEYWORDS: Contract, good faith, implied terms, Bhasin v Hrynew, Yam Seng, interpretation, commercial law. In Bhasin v Hrynew, Cromwell J rightly observed that “[t]he jurisprudence is not always very clear about the source of the good faith obligations found in [contract] cases”.1 Such *Professor of Commercial Law, University College London. I am grateful for the comments of participants at the very stimulating conference on “Good Faith in Contract” held at the Université de Montréal in May 2018 where an earlier version of this article was presented, and especially to Matthew Harrington for the invitation. Even earlier versions of this article were presented at a Chancery Bar Association seminar on “Contractual Discretions” held at the Inner Temple, London, in March 2018, and at a workshop on “Contract Interpretation: A Comparative Discussion” held at the University of Lund, Sweden, in April 2018 (following the very kind 1 Paul Davis Printer's Version 2.0 (Do Not Delete) 5/25/2019 12:31 PM 2 JOURNAL OF COMMONWEALTH LAW [Vol. -

A Casebook on Contract

Contents Preface ix Table of Cases xxv Table of Legislation xlv PART ONE: THE FORMATION OF A CONTRACT 1. OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE 3 1. Introduction 3 (1) What is a Contract? 3 (2) Offer and Acceptance 4 2. Offers and Invitations to Treat 4 (1) Two General Illustrative Cases 5 Harvey v Facey 5 Gibson v Manchester City Council 5 (2) Display of Goods for Sale 7 Fisher v Bell 7 Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd 8 (3) Advertisements 10 Partridge v Crittenden 10 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company 11 (4) Auction Sales 16 Barry v Davies 16 (5) Tenders 19 Spencer v Harding 19 Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Company of Canada (CI) Ltd 20 Blackpool and Fylde Aeroclub Ltd v Blackpool Borough Council 22 3. Acceptance 26 (1) Acceptance by Conduct 26 Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Co 26 (2) 'Battle of the Forms' 27 Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corporation (England) Ltd 27 (3) Communication of Acceptance 33 (a) The General Rule: Acceptance must be Received by Offeror 33 Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corporation 33 Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft mbH 35 (b) Acceptance by Post 37 xii Contents Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Co Ltd v Grant 37 Holwell Securities Ltd v Hughes 39 (c) Waiver by Offeror of the Need for Communication of Acceptance 41 Felt house v Bindley 41 (4) Prescribed Mode of Acceptance 43 Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments Ltd 43 (5) Acceptance in Ignorance of an Offer 45 R v Clarke 45 (6) Acceptance in Unilateral Contracts 47 Errington v Errington 47 4. -

Law for Non-Law Students, Third Edition

LAW FOR NON-LAW STUDENTS Third Edition This book is supported by an online subscription to give you access to periodic updates. To gain access to this area, you need to enter the unique password printed below. The password is protected and your free subscription to the site is valid for 12 months from the date of registration. 1 Go to http://www.cavendishpublishing.com. 2 If you are a registered user of the Cavendish website, log in as usual (with your email address and your personal password). Then click the Law for Non-Law Students button on the home page. You will now see a box next to Law for Non-Law Students. Enter the unique passcode printed below. Once you’ve done that, the word ‘Enter’ appears. Click Enter and that’s where you’ll find your updates. 3 If you are not yet a registered user of the Cavendish website, you will first need to register. Registration is completely free. Click on the ‘Registration’ button at the top of your screen, then type in your email address and a password. You should use something personal and memorable to you. Then click the Law for Non-Law Students button on the home page. You will now see a box next to Law for Non-Law Students. Enter the unique passcode printed below. Once you’ve done that, the word ‘Enter’ appears. Click Enter and that’s where you’ll find your updates 4 Cavendish will email you each time updates are uploaded. All you need to do to obtain any past or future updates is to go to http:// www.cavendishpublishing.com and follow the instructions in point 2 above.