Misrepresentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MODERN LAW of CONTRACT, Eighth Edition

The Modern Law of Contract Eighth Edition Written by a leading author and lecturer with over thirty years’ experience teaching and examining contract law, The Modern Law of Contract continues to equip students with a clear and logical introduction to contract law. Exploring all of the recent developments and case decisions in the field of contract law, it combines a meticulous examination of authorities and commentar- ies with a modern contextual approach. An ideal accessible introduction to con- tract law for students coming to legal study for the first time, this leading textbook offers straightforward explanations of all of the topics found on an undergraduate or GDL contract law module. At the same time, coverage of a variety of theoretical approaches: economic, sociological and empirical encourages reflective thought and critical analysis. New features include: boxed chapter summaries, which help to consolidate learning and understanding; additional ‘For thought’ think points throughout the text where students are asked to consider ‘what if’ scenarios; new diagrams to illustrate principles and facilitate the understanding of concepts and interrelationships; new Key Case close-ups designed to help students identify key cases within contract law and improve their understanding of the facts and context of each case; a Companion Website with half-yearly updates; chapter-by-chapter Multiple Choice Questions; a Flashcard glossary; contract law skills advice; PowerPoint slides of the diagrams within the book; and sample essay questions; new, attractive two-colour text design to improve presentation and help consolidate learning. Clearly written and easy to use, this book enables undergraduate students of contract law to fully engage with the topic and gain a profound understanding of this pivotal area. -

Business Law, Fifth Edition

BUSINESS LAW Fifth Edition This book is supported by a Companion Website, created to keep Business Law up to date and to provide enhanced resources for both students and lecturers. Key features include: ◆ termly updates ◆ links to useful websites ◆ links to ‘ebooks’ for introductory and further reading ◆ ‘ask the author’ – your questions answered www.cavendishpublishing.com/businesslaw BUSINESS LAW Fifth Edition David Kelly, PhD Principal Lecturer in Law Staffordshire University Ann Holmes, M Phil, PGD Dean of the Law School Staffordshire University Ruth Hayward, LLB, LLM Senior Lecturer in Law Staffordshire University Fifth edition first published in Great Britain 2005 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom Telephone: + 44 (0)20 7278 8000 Facsimile: + 44 (0)20 7278 8080 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cavendishpublishing.com Published in the United States by Cavendish Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services, 5804 NE Hassalo Street, Portland, Oregon 97213-3644, USA Published in Australia by Cavendish Publishing (Australia) Pty Ltd 3/303 Barrenjoey Road, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia Email: [email protected] Website: www.cavendishpublishing.com.au © Kelly, D, Holmes, A and Hayward, R 2005 First edition 1995 Second edition 1997 Third edition 2000 Fourth edition 2002 Fifth edition 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Cavendish Publishing Limited, or as expressly permitted by law, or under the terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Contents of a Contract Representations and Misrepresentations

THE LAW OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND CARRIAGE OF GOODS CONTENTS OF A CONTRACT REPRESENTATIONS AND MISREPRESENTATIONS. General definition : A representation is a statement about a factual situation, current or historical, or about a person’s state of mind, including an opinion or belief. Examples include a statement about the condition of a ship or its location, opinions or beliefs about the condition or location of the ship, statements about the vessel’s ability to perform a particular task and statements about where the ship has been or what it has done. A misrepresentation is a false representation. Distinctions : It is important to distinguish representations made as part of negotiations or otherwise, which give rise to remedies in their own right from other statements (or representations) which give rise to actions in other areas of contract. The above must also be distinguished from statements which are of no legal significance whatsoever. A statement may :- a) be a representation which gives rise to remedies discussed in this section; or b) become incorporated as a term of a contract1 for example s12-15 SOGA 1979 ; or c) form the basis of a collateral contract Esso Petroleum v Marsden 2 : Shanklin Pier v Detol Products 3; City of Westminster Properties v Mudd 4 or d) be a mere tradesmanʹs puff as alleged in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co.5 which gives rise to no rights whatsoever since no one relies on them or expects them to be true. e) be a throw away remark, made in jest or casual conversation, with no expectation that anyone might take it seriously or rely upon it. -

Misrepresentation

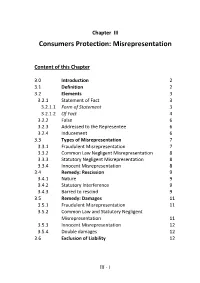

Chapter III Consumers Protection: Misrepresentation Content of this Chapter 3.0 Introduction 2 3.1 Definition 2 3.2 Elements 3 3.2.1 Statement of Fact 3 3.2.1.1 Form of Statement 3 3.2.1.2 Of Fact 4 3.2.2 False 6 3.2.3 Addressed to the Representee 6 3.2.4 Inducement 6 3.3 Types of Misrepresentation 7 3.3.1 Fraudulent Misrepresentation 7 3.3.2 Common Law Negligent Misrepresentation 8 3.3.3 Statutory Negligent Misrepresentation 8 3.3.4 Innocent Misrepresentation 8 3.4 Remedy: Rescission 9 3.4.1 Nature 9 3.4.2 Statutory Interference 9 3.4.3 Barred to rescind 9 3.5 Remedy: Damages 11 3.5.1 Fraudulent Misrepresentation 11 3.5.2 Common Law and Statutory Negligent Misrepresentation 11 3.5.3 Innocent Misrepresentation 12 3.5.4 Double damages 12 3.6 Exclusion of Liability 12 III - 1 3.0 Introduction Misrepresentation is one of the legal grounds reliable for the victim, especially vulnerable consumers, to rescind a contract as well as to claim relief and damages for loss suffered from. The concept of misrepresentation rooted from the common law principal on contract law and later tort. It is important to understand how misrepresentation is constituted at law and each type of misrepresentations. Apart from that, the interference of legislation, i.e. Misrepresentation Ordinance (Cap.284), changed position of remedies in different types of misrepresentation. The legislation also stipulates that the exclusion of liability from misrepresentation shall be subjected to reasonableness. -

The Negotiation Stage

Part I The negotiation stage M02_HALS8786_02_SE_C02.indd 17 7/19/12 3:47 PM M02_HALS8786_02_SE_C02.indd 18 7/19/12 3:47 PM 2 Negotiating the contract Introduction Lord Atkin once remarked that: ‘Businessmen habitually . trust to luck or the good faith of the other party . .’.1 This comment2 provides more than an insight into the motivations of businessmen. It also implicitly acknowledges a limitation of the common law in policing the activities of contractors: the law no more ensures the good faith of your contractual partner than it guarantees your good fortune in business dealings. However, this might not be an accurate description of the purpose of the law relating to pre-contractual negotiations. In an important judgment that was notable for its attempt to place the legal principles under discussion in a broader doctrinal and comparative context Bingham LJ in the Court of Appeal observed that:3 In many civil law systems, and perhaps in most legal systems outside the common law world, the law of obligations recognises and enforces an overriding principle that in making and carrying out contracts parties should act in good faith . It is in essence a principle of fair and open dealing . English law has, characteristically, committed itself to no such overriding principle but has developed piecemeal solutions to demonstrated problems of unfairness. This judgment makes it clear that the gap between civil and common-law jurisdictions is exaggerated by observations at too high a level of generality. While it is true to say that the common law does not explicitly adopt a principle of good faith, it is as obviously untrue to say that the common law encourages bad faith. -

The Modern Law of Contract

THE MODERN LAW OF CONTRACT Fifth edition This book is supported by a Companion Website, created to keep The Modern Law of Contract up to date and to provide enhanced resources for both students and lecturers. Key features include: N termly updates N self-assessment tests N links to useful websites N links to ‘ebooks’ for introductory and further reading N revision guidance N guidelines on answering questions N ‘ask the author’ – your questions answered www.cavendishpublishing.com/moderncontract THE MODERN LAW OF CONTRACT Fifth edition Professor Richard Stone, LLB, LLM Barrister, Gray’s Inn Visiting Professor, University College, Northampton Fifth edition first published in Great Britain 2002 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom Telephone: + 44 (0)20 7278 8000 Facsimile: + 44 (0)20 7278 8080 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cavendishpublishing.com Published in the United States by Cavendish Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services, 5804 NE Hassalo Street, Portland, Oregon 97213-3644, USA Published in Australia by Cavendish Publishing (Australia) Pty Ltd 3/303 Barrenjoey Road, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia This title was originally published in the Cavendish Principles series © Stone, Richard 2002 First edition 1994 Second edition 1996 Third edition 1997 Fourth edition 2000 Fifth edition 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Cavendish Publishing Limited, or as expressly permitted by law, or under the terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Misrepresentation

5 – MISREPRESENTATION Contract law does not have specific principle requiring disclosure, but there are certain cases where it is needed. Where there is misrepresentation, non-disclosure or mistake, the possible responses are: 1. The contract is void ab initio 2. The contract is voidable via rescission 3. The contract can be rectified to correct the mistake (see previous supervisions) 4. Damages can be awarded to remedy the wrong Where the issue is a statement made in course of negotiations, the remedy will depend on classification of the statement: 1. Contractual term (a ‘warranty’) – damages for breach of contract, possibly termination for breach (depending on nature of term) 2. Misrepresentation – rescission (subject to bars), and potential tort or Misrepresentation Act 1967 damages At one point, misrepresentation could be ground for rescission and damages were available only under the tort of deceit if there was fraud; no damages for innocent misrep. In Hedley Byrne v Heller (1964), HOL made clear breach of the DOC to avoid negligent misstatement could give rise to damages. 1967 Misrepresentation Act extended damages under s 2(1) to the case of misrepresentation inducing a contract where the representor cannot prove absence of negligence or bad faith. This made inference of collateral contract less necessary, although still necessary because representations as to future are harder to fit in scope of Act. Categorising statements made in negotiations Mere puffs These have no legal effect, they mean nothing - Dimmock v Hallett (1866) -

Misrepresentation

Misrepresentation Principle Case (1) A false statement Exception to a false statement: if a true representation is falsified by later events, the With v O’Flanagan [1936] Ch 575 change in circumstances should be communicated Dimmock v Hallett (1866) LR 2 Ch App 21; Implied representations: half-truths lead to Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV actionable misrepresentation [2002] EWCA Civ 15 (2) Existing or past fact An opinion is not usually a statement of fact Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177; and therefore not an actionable Hummingbird Motors v Hobbs [1986] RTR 726 misrepresentation An opinion which is either not held or could not Smith v Land and House Property Corporation be held by a reasonable person with the (1884) 28 Ch D 7 speaker’s knowledge is a statement of fact If there is an unequal skill, knowledge, and Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] 2 All bargaining strength, there is misrepresentation ER 5 An actionable misrepresentation is a false Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch D 459; statement of existing fact (i.e. statement of East v Maurer [1991] 1 WLR 461 intention) Kleinwort Benson v Lincoln CC [1999] 2 AC Misrepresentations of law amount to actionable 349; misrepresentations Pankhania v Hackney LBC [2002] EWHC 2441 (Ch) (3) Made by one party to another If a misrepresentation is made to a third party and, objectively, it is likely that the Cramaso LLP v Ogilvie-Grant [2014] AC 1093 misrepresentation will be passed to the other contracting party, it will be actionable (4) Induces the contract The false statement -

A Casebook on Contract

Contents Preface ix Table of Cases xxv Table of Legislation xlv PART ONE: THE FORMATION OF A CONTRACT 1. OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE 3 1. Introduction 3 (1) What is a Contract? 3 (2) Offer and Acceptance 4 2. Offers and Invitations to Treat 4 (1) Two General Illustrative Cases 5 Harvey v Facey 5 Gibson v Manchester City Council 5 (2) Display of Goods for Sale 7 Fisher v Bell 7 Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd 8 (3) Advertisements 10 Partridge v Crittenden 10 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company 11 (4) Auction Sales 16 Barry v Davies 16 (5) Tenders 19 Spencer v Harding 19 Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Company of Canada (CI) Ltd 20 Blackpool and Fylde Aeroclub Ltd v Blackpool Borough Council 22 3. Acceptance 26 (1) Acceptance by Conduct 26 Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Co 26 (2) 'Battle of the Forms' 27 Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corporation (England) Ltd 27 (3) Communication of Acceptance 33 (a) The General Rule: Acceptance must be Received by Offeror 33 Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corporation 33 Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft mbH 35 (b) Acceptance by Post 37 xii Contents Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Co Ltd v Grant 37 Holwell Securities Ltd v Hughes 39 (c) Waiver by Offeror of the Need for Communication of Acceptance 41 Felt house v Bindley 41 (4) Prescribed Mode of Acceptance 43 Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments Ltd 43 (5) Acceptance in Ignorance of an Offer 45 R v Clarke 45 (6) Acceptance in Unilateral Contracts 47 Errington v Errington 47 4. -

Law for Non-Law Students, Third Edition

LAW FOR NON-LAW STUDENTS Third Edition This book is supported by an online subscription to give you access to periodic updates. To gain access to this area, you need to enter the unique password printed below. The password is protected and your free subscription to the site is valid for 12 months from the date of registration. 1 Go to http://www.cavendishpublishing.com. 2 If you are a registered user of the Cavendish website, log in as usual (with your email address and your personal password). Then click the Law for Non-Law Students button on the home page. You will now see a box next to Law for Non-Law Students. Enter the unique passcode printed below. Once you’ve done that, the word ‘Enter’ appears. Click Enter and that’s where you’ll find your updates. 3 If you are not yet a registered user of the Cavendish website, you will first need to register. Registration is completely free. Click on the ‘Registration’ button at the top of your screen, then type in your email address and a password. You should use something personal and memorable to you. Then click the Law for Non-Law Students button on the home page. You will now see a box next to Law for Non-Law Students. Enter the unique passcode printed below. Once you’ve done that, the word ‘Enter’ appears. Click Enter and that’s where you’ll find your updates 4 Cavendish will email you each time updates are uploaded. All you need to do to obtain any past or future updates is to go to http:// www.cavendishpublishing.com and follow the instructions in point 2 above. -

The Modern Law of Contract

THE MODERN LAW OF CONTRACT Fifth edition Professor Richard Stone, LLB, LLM Barrister, Gray’s Inn Visiting Professor, University College, Northampton Fifth edition first published in Great Britain 2002 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom Telephone: + 44 (0)20 7278 8000 Facsimile: + 44 (0)20 7278 8080 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cavendishpublishing.com Published in the United States by Cavendish Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services, 5804 NE Hassalo Street, Portland, Oregon 97213-3644, USA Published in Australia by Cavendish Publishing (Australia) Pty Ltd 3/303 Barrenjoey Road, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia This title was originally published in the Cavendish Principles series © Stone, Richard 2002 First edition 1994 Second edition 1996 Third edition 1997 Fourth edition 2000 Fifth edition 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Cavendish Publishing Limited, or as expressly permitted by law, or under the terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Cavendish Publishing Limited, at the address above. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Stone, Richard, 1951 – The modern law of contract 1 Contracts I Title 346'.02 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available ISBN 1-85941-667-5 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Printed and bound in Great Britain PREFACE My aim in writing this book has been to produce a comprehensive, but readable, account of what I have termed ‘the modern law of contract’. -

Formation: Offer and Acceptance

Formation: Offer and Acceptance How do we know if a contract exists? Þ Offer and acceptance Þ Consideration Þ Intention to be legally bound Þ Certainty of the contract and its terms Þ Some contracts need to be in a certain form Þ Capacity to enter into contract, e.g. a young person cannot enter into a contract Offer: Intention to contract is unequivocal. Agreement: a consensus (meeting of the minds) amongst all parties aBout the arrangement. There must Be objective evidence of the agreement à Not suBjective, there is no agreement if you don’t say or indicate clear agreement/undertaking. Making a commitment: There is an immediate readiness to Be Bound/undertake obligation/assume responsiBility à e.g. language showing commitment or conduct ----- Invitation to Treat (Invitation to Make Offers) Harvey v Facey [1893] Provision of information, not an offer. Fisher v Bell [1961] Shop window invites offers But is not an offer itself. Only providing an example of things they sell, could Be out of stock which is unfair on the shop. A shop is a place of Bargaining, not of definite sales, and you can haggle about the price (outdated in modern conditions). ‘Snapping-up’ cases Ex. Online shopping at Argos The price + description of a TV set is put on the weBsite £2.99. Customer Bought 200 units, and Argos confirmed payment + delivery. Q: Is the weBsite the same as the shop window? ‘Add to Basket’ = offer, payment confirmation = acceptance One party knows/should have known aBout the other’s mistake. In selling, the customer makes the offer.