Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Alberta POD EPDF.Indd

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work. -

Ethnic Minority Writing: the Complexities Surrounding Authenticity, Translation, and Representation in a Global Environment

Ethnic Minority Writing: The Complexities Surrounding Authenticity, Translation, and Representation in a Global Environment Samuel Rose ※ Abstract: This paper discusses the complex issues surrounding authenticity and ethnic minority writing. It also addresses the broader global issues involved when an individual is educated in the West and then attempts to speak for his or her particular ethnic group. The paper concludes with a specifi c example regarding the complexities of translating a Japanese passage into English and discusses the little-known concept of “deterritorialization.” Key words: authenticity, ethnic minority writing, translation and representation, and deterritorialization Who is an authentic ethnic minority writer? How do we know if an individual truly has the authority to speak for his or her particular community? Does a Western education limit one’s ability to speak for his or her ethnic culture? If we assume that an individual does have the authority to speak for a particular group, can his or her writing be translated into another language and still retain the intended meaning? These are just a few of the questions that arise when discussing ethnic minority writing in Western nations. In this essay, I will use Joseph Pivato’s “Representation of Ethnicity as Problem: Essence or Construction” and attempt to answer the questions above. I will then conclude with an example that demonstrates just how complex the problems of representation in ethnic minority writing can be. Identifying with Minorities In the essay “Representation of Ethnicity as Problem: Essence or Construction,” Joseph Pivato writes, “I have often focussed on the voice of the writer and his/her authority to speak about the minority experi- ence” (Literary Pluralities, p. -

AAM. Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature, Ddavies

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Davies, D. ORCID: 0000-0002-3584-5789 (2021). Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature: Reading Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black. The Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 8(1), pp. 1-23. doi: 10.1017/pli.2020.23 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/26525/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/pli.2020.23 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature: Reading Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black Abstract (151 words) Through an extended reading of Canadian author Esi Edugyan’s novel, Washington Black (2018), this article aims to revise and reinsert both the practice of close reading and a radically revised humanism back into recent World(-)Literature debates. -

Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing

UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu> CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb> Purdue University Press ©Purdue University The Library Series of the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access quarterly in the humanities and the social sciences CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture publishes scholarship in the humanities and social sciences following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the CLCWeb Library Series are 1) articles, 2) books, 3) bibliographies, 4) resources, and 5) documents. Contact: <[email protected]> Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweblibrary/canadianethnicbibliography> Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, Asma Sayed, and Domenic A. Beneventi 1) literary histories and bibliographies of canadian ethnic minority writing 2) work on canadian ethnic minority writing This selected bibliography is compiled according to the following criteria: 1) Only English- and French-language works are included; however, it should be noted that there exists a substantial corpus of studies in a number Canada's ethnic minority languages; 2) Critical works about the literatures of Canada's First Nations are not included following the frequently expressed opinion that Canadian First Nations literatures should not be categorized within Canadian "Ethnic" writing but as a separate corpus; 3) Literary criticism as well as theoretical texts are included; 4) Critical texts on works of authors writing in English and French but usually viewed or which could be considered as "Ethnic" authors (i.e., immigré[e]/exile individuals whose works contain Canadian "Ethnic" perspectives) are included; 5) Some works dealing with US or Anglophone-American Ethnic Minority Writing with Canadian perspectives are included; 6) M.A. -

Oltreoceano15 Tagliato

ITALIAN CANADIAN WRITING: THE DIFFERENCE A FEW DECADES MAKE* Linda Hutcheon** The article explores the changes in the last 40 years both in the language of Canadian ethnic literature itself and in its authors’ self-identifying as Italian Canadian in light of the deve- lopments of those years both in ‘identity politics’ and in Canada’s national sense of selfhood. En route it tests the usefulness of various labels used, over time, to identify these writings against the literary corpus produced for almost thirty years now by Nino Ricci, born and raised in Canada, by Italian immigrant parents. Scrittura italo-canadese: pochi decenni possono fare la differenza Il contributo analizza i cambiamenti che negli ultimi quaranta anni si sono verificati nel lin- guaggio, utilizzato per definire la letteratura etnica canadese, e nel modo in cui gli autori si sono identificati come italo-canadesi a fronte sia delle mutate politiche identitarie sia degli sviluppi nel senso nazionale di identità canadese, susseguitisi in quell’arco temporale. Per testare la validità delle varie etichette utilizzate via via per definire tale letteratura, viene esaminato il corpus letterario, ormai trentennale, prodotto da Nino Ricci, scrittore nato e cresciuto in Canada da genitori immigranti di origine italiana. To Begin With a Story In the mid-1990s – in another century and in another country – I was invited to participate in a panel dedicated to the topic of “Ethnicity and Writing/ Reading” at the annual conference of the Modern Language Association of * This article began life as the Pugliese-Zorzi Italian Canadian Studies Lecture presented in February 2018 to the Canadian Studies Program and the University College Alumni, Uni- versity of Toronto. -

Canada & Beyond 5 (2015): 27 Liminality and (Trans)Nationalism in the Rethinking of African Canadian Subjectivity: Esi Edugy

Liminality and (Trans)Nationalism in the Rethinking of African Canadian Subjectivity: Esi Edugyan’s The Second Life of Samuel Tyne. Vicent Cucarella-Ramon Universitat de València Canada is a location where…blackness is threatened with psychological evisceration (George Elliott Clarke, Odysseys Home) In a Canadian context, writing blackness is a scary scenario: we are an absented presence always under erasure (Rinaldo Walcott , Black Like Who) Who is to say what a Canadian story looks like, where it should be set, who should be telling it?…Indeed, what is a Canadian at all? (Esi Edugyan, Dreaming of Elsewhere) Introduction The publication of Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness in 1993 marked an ontological shift in the recognition of the diversity and conflict in black experiences and their cultural production. There exists an established consensus on the impact and groundbreaking potential of Gilroy’s work as it propounded a global reconfiguration of the notion of a multilayered black self. Gilroy repositioned black consciousness from the margins to the center, engaging a transnational and transcultural debate that contributed to securing black subjectivity as “a central symbol in the psychological, cultural, and political systems of the West as a whole” (Gilroy 158). However, in the late 1990s Gilroy’s theory generated debates over its shortcomings, namely because new readings of The Black Atlantic pointed out that the social realities of Africa, the Caribbean and Canada were absent from its theoretical -

TöTã¶Sy De Zepetnek, Steven Curriculum Vitae

& PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS & PURDUE SCHOLARLY PUBLISHING <http://www.purdue.edu> <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu> West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 USA <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweblibrary/totosycv> curriculum vitae & lists of publications of TÖTÖSY de ZEPETNEK, Steven PhD Professor (retired) Full Professor, Honorary Professor, Assistant Professor, Lecturer, 1984-: University of Alberta, University of Halle-Wittenberg, National Sun Yat-sen University, Sichuan University, (distinguished) Visiting Professor at universities in Asia, Europe, India, USA Editor, Associate Editor, Assistant Editor, Editorial Assistant of learned journals and monograph series of books 1981-: Carleton University, University of Alberta, Canadian Comparative Literature Association/ Association Canadienne de Littérature Comparée, Shaker Press, Purdue University Press, Routledge Press Elected Member 2015- Academia Scientiarum et Artium Europaea/European Academy of Sciences and Arts ORCID: Connecting Research and Researchers ID 0000-0002-1506-0159 <http://orcid.org/> Clarivate (formerly Thomson Reuters): Researcher ID F-1053-2011 <http://www.researcherid.com/> contact: <[email protected]> 1) bioprofile 2) fields of scholarship & teaching 3) academic appointments & service 4) publications 5) funding for research & publishing scholarship 6) conference organization & participation 1) bioprofile: Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek's research, teaching, and publications are in comparative literature, comparative cul- tural studies, and media and communication studies including postcolonial studies, (im)migration & ethnic minority studies, fem- inist & gender studies, film & literature, digital humanities, education & cultural policy, readership & audience studies, Holocaust studies, online course design in the humanities, editing & publishing in print & digital, conflict management & diversity training, history (genealogy and heraldry). Education: Ph.D. 1989 Comparative Literature University of Alberta; B.Ed. 1984 History and English as a Second Language University of Ottawa; M.A. -

Ms. Clarke, George Elliott Coll. Papers 00206B 1 Gift of George Elliott

Ms. Clarke, George Elliott Coll. Papers 00206B Gift of George Elliott Clarke 2015 Includes extensive drafts, notes, research for his many projects; personal and professional correspondence; appearances; teaching; early material from the 1980s; Whylah Falls; One Heart Broken Into Song; The Motorcyclist; Illicit Sonnets; Red; Saltwater Spirituals and Deeper Blues; prose; poem drafts; essays; articles; reviews; columns; B.A. and M.A. course work University of Waterloo, Queen’s; typescript poems by John Thompson for Stilt Jack and other material related to the life and work of George Elliott Clarke Arrangement: Contains series: Series 1: The Motorcyclist Boxes 1-5 Series 2: Writing/Manuscripts Boxes 6-25 Series 3: Correspondence, 1980s – 2014, Boxes 26-81 Series 4: Ideas, Boxes 82-86 Series 5: Africana, Boxes 87-88 Series 6: Other material, including publicity and work by others, Boxes 89-108 Series 7: Stilt Jack John Thompson typescript poems, Box 109 Series 8: George Hamilton/family/personal, Box 110 Note: extensive correspondence includes family/friends/personal, as well as M. Nourbese Philip, Althea Prince, Paul Zemokhol, Joe Sealy, Fil Fraser and a wide variety of Canadian and international writers, artists, musicians, politicians, and others Extent: 110 boxes and items (17 metres) Note: Boxes 55, 58 and 59 have been removed. Series 1: The Motorcyclist First and later drafts, comments and notes for the new novel, based in part on a year, 1959-1960, of the diaries of George Elliott Clarke’s father, William Lloyd Clarke. Box 1 The Motorcyclist 2 items in box First draft, holograph notebooks, Books I and II 1 Ms. -

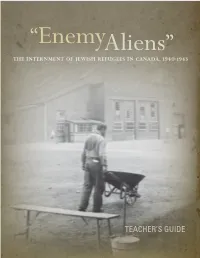

Complete Teachers' Guide to Enemy

“EnemyAliens” The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 TEACHER’S GUIDE “ENEMY ALIENS”: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 © 2012, Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre Lessons: Nina Krieger Text: Paula Draper Research: Katie Powell, Katie Renaud, Laura Mehes Translation: Myriam Fontaine Design: Kazuko Kusumoto Copy Editing: Rome Fox, Anna Migicovsky Cover image: Photograph of an internee in a camp uniform, taken by internee Marcell Seidler, Camp N (Sherbrooke, Quebec), 1940-1942. Seidler secretly documented camp life using a handmade pinhole camera. − Courtesy Eric Koch / Library and Archives Canada / PA-143492 Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre 50 - 950 West 41st Avenue Vancouver, BC V5Z 2N7 604 264 0499 / [email protected] / www.vhec.org Material may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes provided that the publisher and author are acknowledged. The exhibit Enemy Aliens: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940 – 1943 was generously funded by the Community Historical Recognition Program of the Department of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism Canada. With the generous support of: Oasis Foundation The Ben and Esther Dayson Charitable Foundation The Kahn Family Foundation Isaac and Sophie Waldman Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Foundation Frank Koller The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre gratefully acknowledges the financial investment by the Department of Canadian Heritage in the creation of this online presentation for the Virtual Museum of Canada. Teacher’s Guide made possible through the generous support of the Mordehai and Hana Wosk Family Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Holocaust Centre Society. With special thanks to the former internees and their families, who generously shared their experiences and artefacts in the creation of the exhibit. -

Writing Alberta POD EPDF.Indd

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work. -

Writing Alberta POD EPDF.Indd

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work. -

Hiromi Goto's Chorus of Mushrooms

ISSN 0214-4808 ● CODEN RAEIEX Editor Emeritus Pedro Jesús Marcos Pérez Editors José Mateo Martínez Francisco Yus Editorial Board Asunción Alba (UNED) ● Román Álvarez (University of Salamanca) ● Norman F. Blake (University of Sheffi eld) ● Juan de la Cruz (University of Málaga) ● Bernd Dietz (University of La Laguna) ● Angela Downing (University of Madrid, Compluten se) ● Francisco Fernández (University of Valen cia) ● Fernando Galván (University of Alcalá) ● Francisco García Tortosa (University of Seville) ● Pedro Guardia (University of Barcelona) ● Ernst-August Gutt (SIL) ● Pilar Hidalgo (Univer sity of Málaga) ● Ramón López Ortega (University of Extremadura) ● Doireann MacDermott (Universi ty of Barcelona) ● Catalina Montes (Uni- versity of Salamanca) ● Susana Onega (University of Zaragoza) ● Esteban Pujals (Uni ver sity of Madrid, Complutense) ● Julio C. Santoyo (University of León) ● John Sinclair (Uni versity of Birmingham) Advisory Board Enrique Alcaraz Varó (University of Alicante) ● Manuel Almagro Jiménez (University of Seville) ● José Antonio Álvarez Amorós (University of La Coruña) ● Antonio Bravo García (University of Oviedo) ● Miguel Ángel Campos Pardillos (University of Alicante) ● Silvia Caporale (University of Alicante) ● José Carnero González (Universi ty of Seville) ● Fernando Cerezal (University of Alcalá) ● Ángeles de la Concha (UNED) ● Isabel Díaz Sánchez (University of Alicante) ● Teresa Gibert Maceda (UNED) ● Teresa Gómez Reus (University of Alicante) ● José S. Gómez Soliño (Universi ty of La Laguna) ● José Manuel González (University of Alicante) ● Brian Hughes (University of Alicante) ● Antonio Lillo (University of Alicante) ● José Mateo Martínez (University of Alicante) ● Cynthia Miguélez Giambruno (University of Alicante) ● Bryn Moody (University of Alicante) ● Ana Isabel Ojea López (University of Oviedo) ● Félix Rodríguez González (Universi ty of Alicante) ● María Socorro Suárez (University of Oviedo) ● Justine Tally (University of La Laguna) ● Francisco Javier Torres Ribelles (University of Alicante) ● M.