Efficacy and Safety of Metronomic Chemotherapy Versus Palliative Hydroxyurea in Unfit Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients: a Multicenter, Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certification of Quality Management System for Medical Laboratories Complying with Medical Laboratory Standard, Ministry of Public Health

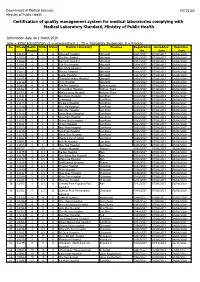

Department of Medical Sciences F0715102 Ministry of Public Health Certification of quality management system for medical laboratories complying with Medical Laboratory Standard, Ministry of Public Health Information date on 1 March 2019 new = initial accreditation, r1 = reassessment 1 , TS = Temporary Suspension, P = Process No. HCode Health RMSc Status Medical Laboratory Province Registration Accredited Expiration Region No. Date Date 1 10673 2 2 r1 Uttaradit Hospital Uttaradit 0001/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 2 11159 2 2 r1 Tha Pla Hospital Uttaradit 0002/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 3 11160 2 2 r1 Nam Pat Hospital Uttaradit 0003/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 4 11161 2 2 r1 Fak Tha Hospital Uttaradit 0004/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 5 11162 2 2 r1 Ban Khok Hospital Uttaradit 0005/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 6 11163 2 2 r1 Phichai Hospital Uttaradit 0006/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 7 11164 2 2 r1 Laplae Hospital Uttaradit 0007/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 8 11165 2 2 r1 ThongSaenKhan Hospital Uttaradit 0008/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 9 11158 2 2 r1 Tron Hospital Uttaradit 0009/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 10 10863 4 4 r1 Pak Phli Hospital Nakhonnayok 0010/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 11 10762 4 4 r1 Thanyaburi Hospital Pathum Thani 0011/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 12 10761 4 4 r1 Klong Luang Hospital Pathum Thani 0012/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 13 11141 1 1 P Ban Hong Hospital LamPhun 0014/2557 07/08/2014 06/08/2017 14 11142 1 1 P Li Hospital LamPhun 0015/2557 07/08/2014 06/08/2017 15 11144 1 1 P Pa Sang Hospital LamPhun 0016/2557 07/08/2014 06/08/2017 -

Cover Tjs 35-4-57

ISSN 0125-6068 TheThai Journal of SURGERY Official Publication of the Royal College of Surgeons of Thailand www.surgeons.or.th/ejournal Volume 35 October-December 2014 Number 4 ORIGINAL ARTICLES 121 Comparison between Ventriculoatrial Shunt and Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt: Revision Rate and Complications Korrapakc Wangtanaphat, Porn Narischart 126 Open Surgical Management of Atherosclerotic Aortoiliac Occlusive Diseases (AIOD) Type 1 Anuwat Chantip 130 “Sawanpracharak” Connector: A Single Tube Intercostal Drainage Connector Wanchai Manakijsirisuthi 134 The Trainee’s Operative Experiences for General Surgery in Thailand Potchavit Aphinives CASE REPORT 139 Mitral and Tricuspid Valve Replacement in Uncommon Case of Situs Inversus with Dextrocardia Nuttapon Arayawudhikul, Boonsap Sakboon, Jareon Cheewinmethasiri, Angsu Chartirungsun, Benjamaporn Sripisuttrakul ABSTRACTS 143 Abstracts of the 39th Annual Scientific Congress of the Royal College of Surgeons of Thailand, 10-13 July 2014, Ambassador City Jomtien Hotel, Jomtien, Pattaya, Cholburi, Thailand (Part II) 169 Index Secretariat Office : Royal Golden Jubilee Building, 2 Soi Soonvijai, New Petchaburi Road, Huaykwang, Bangkok 10310, Thailand Tel. +66 2716 6141-3 Fax +66 2716 6144 E-mail: [email protected] www.surgeons.or.th The THAI Journal of SURGERY Official Publication of the Royal College of Surgeons of Thailand Vol. 35 October - December 2014 No. 4 Original Article Comparison between Ventriculoatrial Shunt and Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt: Revision Rate and Complications Korrapakc Wangtanaphat, MD Porn Narischart, MD Prasat Neurological Institute, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Pubic Health, Bangkok, Thailand Abstract Background and Objective: Hydrocephalus is a common problem in neurosurgical field. In current clinical practice guidelines, ventriculoatrial shunt and ventriculoperitoneal shunt are recommended treatment options. No previous study reported differences between two procedures in term of complications and revision rates. -

September 2008 October 2008 R Dirty Pending Final 1 101 พระพุทธบาท

September 2008 October 2008 November 2008 No Site No. Hospital Name Record Status Total Cases Total Cases Total Cases Total Records r Dirty Pending Final 1 101 พระพุทธบาท สระบุรี Phraphuthabat Hospital 1129126 2 102 พญาไท ศรีราชา ชลบุรี Phyathai Sriracha Hospital 0116501 3 103 เวชศาสตรเขตรอน The Hospital for Tropical Medicine 0000000 4 104 ระยอง Rayong Hospital 155204016 5 105 รวมแพทยระยอง Ruampat Rayong 0000000 6 106 คลีนิคแพทยสุชาดา ระยอง Suchada Clinic 0000000 7 107 สงขลา Songkhla Hospital 0014202 8 108 สรรพสิทธิประสงค อุบลราชธานี Sapasittiprasong Hospital 10 21 30 120 19128 9 109 พระรามเกา Praram 9 Hospital 0000000 10 110 บําราศนราดูร นนทบุรี Bamrasnaradura Infectious Diseases Institute 0116132 11 111 ชลบุรี Chonburi Hospital 023120012 12 112 ธรรมศาสตรเฉลิมพระเกียรติ ปทุมธานี Thammasat University Hospital 0228017 13 113 เจาพระยา Chaophya Hospital 0000000 14 114 สงขลานครินทร สงขลา Songkhlanakarin Hospital 00416547 15 115 มูลนิธิโรคไต ณ โรงพยาบาลสงฆ The Kidney Foundation of Thailand 0000000 16 116 นพรัตนราชธานี Nopprat Rajathanee Hospital 036240717 17 117 พระจอมเกลา เพชรบุรี Phra Chom Klao Hospital Petburi 0000000 18 118 พระมงกุฎเกลา (กุมาร) Phramongkutklao Hospital, (Pediatrics) 0000000 19 119 สุราษฎรธานี Surat Thani Hospital 12 12 14 55 1054 20 120 รามาธิบดี Ramathibodi Hospital 0000000 21 121 วชิรพยาบาล Vajira Hospital 1112020 22 122 บานแพว สมุทรสาคร Banphaeo Hospital 1116501 23 123 สวรรคประชารักษ นครสวรรค Sawanpracharak Hospital 00312066 24 124 จุฬาลงกรณ Chulalongkorn Hospital 18 19 20 79 26 35 18 25 125 บํารุงราษฎร Bumrungrad International 0000000 26 126 ทักษิณ สุราษฎรธานี Thaksin Hospital 0000000 27 127 คายวิภาวดีรังสิต Fort Wiphavadirangsit Hospital 22215771 28 128 พระนครศรีอยุธยา Pranakornsriayudhaya Hospital 0000000 29 129 อุดรธานี Udonthani Hospital 19 22 28 112 26 57 29 30 130 ศรีนครินทร ม.ขอนแกน Srinakarin Hospital, Khon Kaen University 0000000 31 131 หนองคาย Nongkhai Hospital 0000000 32 132 ศิริราช Siriraj Hospital 1111010 Page 1 of 2 28 Jul 2008 September 2008 October 2008 November 2008 No Site No. -

Clinical Epidemiology of 7126 Melioidosis Patients in Thailand and the Implications for a National Notifiable Diseases Surveilla

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Open Forum Infectious Diseases provided by Apollo MAJOR ARTICLE Clinical Epidemiology of 7126 Melioidosis Patients in Thailand and the Implications for a National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System Viriya Hantrakun,1, Somkid Kongyu,2 Preeyarach Klaytong,1 Sittikorn Rongsumlee,1 Nicholas P. J. Day,1,3 Sharon J. Peacock,4 Soawapak Hinjoy,2,5 and Direk Limmathurotsakul1,3,6, 1Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU), Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2 Epidemiology Division, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand, 3 Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, Old Road Campus, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 5 Office of International Cooperation, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand, and 6 Department of Tropical Hygiene, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand Background. National notifiable diseases surveillance system (NNDSS) data in developing countries are usually incomplete, yet the total number of fatal cases reported is commonly used in national priority-setting. Melioidosis, an infectious disease caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, is largely underrecognized by policy-makers due to the underreporting of fatal cases via the NNDSS. Methods. Collaborating with the Epidemiology Division (ED), Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), we conducted a retrospec- tive study to determine the incidence and mortality of melioidosis cases already identified by clinical microbiology laboratories nationwide. A case of melioidosis was defined as a patient with any clinical specimen culture positive for B. -

Saturday 5 September 2015

SATURDAY 5 SEPTEMBER 2015 SATURDAY 5 SEPTEMBER Registration Desk 0745-1730 Registration Desk, SECC for Pre-conference Workshop and Course Participants Location: Hall 4, SECC Group Meeting 1000-1700 AMEE Executive Committee Meeting (Closed Meeting) Location: Green Room 10, Back of Hall 4 AMEE-Essential Skills in Medical Education (ESME) Courses Pre-registration is essential and lunch will be provided. 0830-1700 ESME – Essential Skills in Medical Education Location: Argyll I, Crowne Plaza 0845-1630 ESMEA – Essential Skills in Medical Education Assessment Location: Argyll III, Crowne Plaza 0845-1630 RESME – Research Essential Skills in Medical Education Location: Argyll II, Crowne Plaza 0845-1700 ESMESim - Essential Skills in Simulation-based Healthcare Instruction Location: Castle II, Crowne Plaza 0900-1700 ESCEPD – Essential Skills in Continuing Education and Professional Development Location: Castle 1, Crowne Plaza 1000-1330 ESCEL – Essential Skills in Computer-Enhanced Learning Location: Carron 2, SECC Course Pre-registration is essential and lunch will be provided. 0830-1630 ASME-FLAME - Fundamentals of Leadership and Management in Education Location: Castle III, Crowne Plaza Masterclass Pre-registration is essential and lunch will be provided. 0915-1630 MC1 Communication Matters: Demystifying simulation design, debriefing and facilitation practice Kerry Knickle (Standardized Patient Program, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada); Nancy McNaughton, Diana Tabak) University of Toronto, Centre for Research in Education, Standardized -

Course Description of Bachelor of Science in Paramedicine 1. General Education 1.1 Social Sciences and Humanities MUGE 101 Gener

Course Description of Bachelor of Science in Paramedicine 1. General Education 1.1 Social Sciences and Humanities MUGE 101 General Education for Human Development Pre-requisite - Well-rounded graduates, key issues affecting society and the environment with respect to one’ particular context; holistically integrated knowledge to identify the key factors; speaking and writing to target audiences with respect to objectives; being accountable, respecting different opinions, a leader or a member of a team and work as a team to come up with a systematic basic research-based solution or guidelines to manage the key issues; mindful and intellectual assessment of both positive and negative impacts of the key issues in order to happily live with society and nature SHHU 125 Professional Code of Ethics Pre-requisite - Concepts and ethical principles of people in various professions, journalists, politicians, businessmen, doctors, government officials, policemen, soldiers; ethical problems in the professions and the ways to resolve them SHSS 144 Principles of Communication Pre-requisite - The importance of communication; information transferring, understanding, language usage, behavior of sender and receiver personality and communication; effective communication problems in communication SHSS 250 Public Health Laws and Regulations Pre-requisite - Introduction to law justice procedure; law and regulation for doctor and public health practitioners, medical treatment act, practice of the art of healing act, medical service act, food act, drug act, criminal -

Development of Palliative Care Model Using Thai Traditional Medicine for Treatment of End-Stage Liver Cancer Patients in Thai Traditional Medicine Hospitals

DEVELOPMENT OF PALLIATIVE CARE MODEL USING THAI TRADITIONAL MEDICINE FOR TREATMENT OF END-STAGE LIVER CANCER PATIENTS IN THAI TRADITIONAL MEDICINE HOSPITALS By MR. Preecha NOOTIM A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy (SOCIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE PHARMACY) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2019 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University - โดย นายปรีชา หนูทิม วทิ ยานิพนธ์น้ีเป็นส่วนหน่ึงของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตรเภสัชศาสตรดุษฎีบณั ฑิต สาขาวิชาเภสัชศาสตร์สังคมและการบริหาร แบบ 1.1 เภสัชศาสตรดุษฎีบัณฑิต บัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร ปีการศึกษา 2562 ลิขสิทธ์ิของบณั ฑิตวทิ ยาลยั มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร DEVELOPMENT OF PALLIATIVE CARE MODEL USING THAI TRADITIONAL MEDICINE FOR TREATMENT OF END-STAGE LIVER CANCER PATIENTS IN THAI TRADITIONAL MEDICINE HOSPITALS By MR. Preecha NOOTIM A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy (SOCIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE PHARMACY) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2019 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University Title Development of Palliative Care Model Using Thai Traditional Medicine for Treatment of End-stage Liver Cancer Patients in Thai Traditional Medicine Hospitals By Preecha NOOTIM Field of Study (SOCIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE PHARMACY) Advisor Assistant Professor NATTIYA KAPOL , Ph.D. Graduate School Silpakorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Dean of graduate school (Associate Professor Jurairat Nunthanid, Ph.D.) Approved by Chair -

Acute Poisoning Surveillance in Thailand: the Current State of Affairs and a Vision for the Future

Hindawi Publishing Corporation ISRN Emergency Medicine Volume 2013, Article ID 812836, 9 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/812836 Review Article Acute Poisoning Surveillance in Thailand: The Current State of Affairs and a Vision for the Future Jutamas Saoraya1 and Pholaphat Charles Inboriboon2 1 Emergency Department, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand 2 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Jutamas Saoraya; [email protected] Received 17 October 2013; Accepted 19 November 2013 Academic Editors: A. Eisenman, C. R. Harris, and O. Karcioglu Copyright © 2013 J. Saoraya and P. C. Inboriboon. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Acute poisoning is a major public health threat worldwide, including Thailand, a country in Southeast Asia with over 67 million inhabitants. The incidence and characteristics of poisoning in Thailand vary greatly depending on the reporting body. This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive description of the state of poisoning in Thailand. It identifies common trends and differences in poisoning by reporting centers and regional studies. Almost half of the cases and three-fourths of the deaths involved pesticide poisonings associated with agricultural occupations. However, increasing urbanization has led to an increase in drug and household chemical poisoning. Though the majority of reported poisonings remain intentional, a trend towards unintentional poisonings in pediatric and geriatric populations should not be dismissed. -

In Vitro Activity of Biapenem and Comparators Against Multidrug

Pharmaceutical Sciences Asia Pharm Sci Asia 2020; 47 (4), 378-386 DOI:10.29090/psa.2020.04.019.0072 Research Article In vitro activity of biapenem and comparators against multidrug-resistant and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from tertiary care hospitals in Thailand Jantana Houngsaitong1, Preecha Montakantikul1, Taniya Paiboonwong1, ABSTRACT 2 Mullika Chomnawang , Acinetobacter baumannii is one of nosocomial pathogen 2 Piyatip Khuntayaporn , which emerges as multidrug-resistance worldwide. Multidrug- 1* Suvatna Chulavatnatol resistant A. baumannii (MDRAB) and carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) are highly concerned due to limitation of 1 Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand therapeutic options. Antibacterial activity of biapenem was explored 2 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of in order to overcome bacterial resistance. A total of 412 A. baumannii Pharmacy, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand clinical isolates from 13 tertiary care hospitals in Thailand were collected. MIC values of biapenem and comparators; imipenem, meropenem, colistin, sulbactam, ciprofloxacin ceftazidime and *Corresponding author: fosfomycin sodium, were determined by broth microdilution Suvatna Chulavatnatol [email protected] method in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (2016). In total, 320 isolates (77.67%) were MDRAB and 328 isolates (79.61%) were CRAB while 58 isolates (14.07%) were colistin-resistant AB. A. baumannii showed widespread resistance to ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin KEYWORDS: and carbapenems in more than 90% of the strains; resistance to Biapenem; Multidrug-resistant A. sulbactam, fosfomycin, and colistin were 85%, 60%, and 15% Baumannii; Carbapenem-resistant respectively. By comparison among carbapenems, biapenem showed MIC of 16/32 which were at least 2 folds lower A. -

ASSOCIATED GENES, and GENOTYPE of METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS Clinical ISOLATES from NORTHERN THAILAND

SOUTHEAST ASIAN J TROP MED PUBLIC HEALTH ANTIBIOGRAM, ANTIBIOTIC AND DISINFECTANT RESISTANCE GENES, BIOFILM-PRODUCING AND -ASSOCIATED GENES, AND GENOTYPE OF METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS CLINIcaL ISOLATES FROM NORTHERN THAILAND Rathanin Seng1, Thawatchai Kitti2, Rapee Thummeepak3, Autchasai Siriprayong3, Thitipan Phukao3, Phattaraporn Kongthai3, Thanyasiri Jindayok4, Kwanjai Ketwong5, Chalermchai Boonlao6 and Sutthirat Sitthisak3,7 1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok; 2Faculty of Oriental Medicine, Chiang Rai College, Chiang Rai; 3Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medical Science, 4Division of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok; 5Sawanpracharak Hospital, Amphoe Meuang, Nakhon Sawan; 6Chiang Rai Prachanukroh Hospital, Amphoe Meuang, Chiang Rai; 7Centre of Excellence in Medical Biotechnology, Faculty of Medical Science, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand Abstract. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) causes a variety of infectious diseases in both hospital and community. The study determined preva- lence of antibiotic resistance and associated genes, biofilm-producing phenotype and associated genes, SCCmec types, and clonal subtype ST239 of MRSA clinical isolates obtained from three hospitals in northern Thailand during January 2013 to October 2015. Some 95% of MRSA isolates were multidrug resistant, with 82%, 60% and 47% harboring ermA, ermB and qacAB, respectively. Although all MRSA isolates were positive for slime (biofilm) production on Congo red agar, quan- titative measurement of biofilm generation using microtiter plate assay (MTP) indicated 60% were low biofilm producers, with prevalence of biofilm-associated genes, bab, cna, fnbA, and icaAD, ranging from 50% to 100%. MRSA SCCmec type III was predominant, but the presence of SCCmec type IV and type V (albeit at low frequency) indicated acquisition of community-acquired infection. -

KHON KAEN Udon Thani 145 X 210 Mm

KHON KAEN Udon Thani 145 x 210 mm. Phrathat Kham Kaen CONTENTS KHON KAEN 8 City Attractions 9 Out-Of-City Attractions 15 Special Events 32 Local Product and Souvenirs 32 Suggested Itinerary 33 Golf Courses 35 Restaurants and Acoomodation 36 Important Telephone Numbers 36 How To Get There 36 UDON THANI 38 City Attractions 39 Out-Of-City Attractions 43 Special Events 51 Local Products and Souvenirs 52 Golf Courses 52 Suggested Itinerary 52 Important Telephone Numbers 55 How To Get There 55 Khon Kaen Khon Kaen Udon Thani Wat Udom Khongkha Khiri Khet Khon kaen Khon Kaen was established as a city over two hundred years ago during the reign of King Rama I, but the natural and historical evidences found in the area indicated that its history dates back much further. The ancient Khmer ruins, traces of human settlement in the prehistoric period, and the fossils of dinosaurs have proven the remarkable history and culture of Khon Kaen since millions of years ago. The strategic location at the heart of the Northeastern region makes Khon Kaen a hub of education, technology, commercial, trans- portation, and handicrafts of the region. One of the most famous crafts that illustrated the time-honoured local wisdom of Thai people is Mudmee silk and the production centre of this exquisite textile is in Khon Kaen. Khon Kaen boasts a diversity of attractions that makes for a memorable holiday where visitors can enjoy exploring a combination of breath taking natural wonders, fascinating historical treasures and cultural heritage, unique way of life, and extraordinary local wisdom. -

Risk Prediction Score of Death in Traumatised and Injured Children

RISK PREDICTION SCORE OF DEATH IN TRAUMATISED AND INJURED CHILDREN SAKDA ARJ-ONG VALLIPAKORN A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (CLINICAL EPIDEMIOLOGY) FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES MAHIDOL UNIVERSITY 2013 COPYRIGHT OF MAHIDOL UNIVERSITY Thesis entitled RISK PREDICTION SCORE OF DEATH IN TRAUMATISED AND INJURED CHILDREN ............................................................ Mr.Sakda Arj-ong Vallipakorn Candidate ............................................................ Asst.Prof.Ammarin Thakkinstian, Ph.D. Major advisor ............................................................. Prof.Paibul Suriyawongpaisal, M.D., M.Sc. Co-advisor ............................................................ Assoc.Prof.Adisak Plitapolkarnpim, M.D., M.P.H. Co-advisor ......................................................... ............................................................ Prof.Banchong Mahaisavariya, M.D., Asst.Prof. Dr.Ammarin Thakkinstian, Ph.D. Dip Thai Board of Orthopedics Program Director Dean Doctor of Philosophy Program in Faculty of Graduate Studies Clinical Epidemiology Mahidol University Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital Mahidol University Thesis entitled RISK PREDICTION SCORE OF DEATH IN TRAUMATISED AND INJURED CHILDREN was submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies, Mahidol University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Clinical Epidemiology) on July 4,2013 ………………………………………. Mr.Sakda Arj-ong Vallipakorn Candidate ………………………………………. Lect.Vijj Kasemsup,