Chestertonian Dramatology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heythrop College London G.K. Chesterton's Concept Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Heythrop College Publications HEYTHROP COLLEGE LONDON G.K. CHESTERTON’S CONCEPT OF HOLINESS IN DAILY LIFE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY MARTINE EMMA THOMPSON LONDON 2014 1 Abstract The term holiness and the concept of sainthood have come under much scrutiny in recent times, both among theologians and the modern laity. There is a sense that these terms or virtues belong to an age long past, and that they are remote and irrelevant to modern believers; that there is the ‘ideal’ but that it is not seriously attainable in a secular, busy modern world with all its demands. Moreover, many believe that sainthood is accessible only to the very few, attained by those who undergo strict ascetic regimes of self-denial and rejection of a ‘normal’ life. However, these conceptions of holiness are clearly at odds with, and may be challenged by others, including the Roman Catholic Church’s teaching of a ‘universal call to holiness’. One of the aims of this thesis is to address those misconceptions with particular focus upon the theological concepts of the writer G.K. Chesterton and his understanding of holiness in the ordinary. Having been a popular writer and journalist, it has proved difficult for some academics and laypeople to accept Chesterton as a theologian. Furthermore, Chesterton considered himself to be an ordinary man, he did not belong to a religious order or community, and yet he was a theological writer who formulated an original conception of holiness in the ordinary. -

2015-2016 Annual Report Mission: to Strengthen Minnesota’S Independent Schools Through Advocacy and Advancement

2015-2016 ANNUAL REPORT Mission: To strengthen Minnesota’s independent schools through advocacy and advancement. Global Perspective Equitable Access Kids CORE VALUES Truth Collaboration Choice Quality Dear friends of Minnesota Independent School Forum: • More than $129,000 in STEM grants were distributed to We acknowledge and thank our generous funders, donors, sponsors 33 schools. These grants and collaborative partners for the investment of time, talent and provided funding for hands- financial resources to support independent and private schools. This on projects in our member support is vital as we connect and convene a cohort of 155 member schools across Minnesota. schools across Minnesota. We also thank our member schools, who prioritize their connection and involvement in a vast network of stu- • Through our Opportunity for dents, educators and leaders. All Kids (OAK) coalition, sig- nificant progress was made toward enhancing educational choice in This year was very successful and illustrated a highly active and Minnesota. We are committed to advancing these legislative priori- engaged membership. During the 2015-16 year: ties for the benefit of all students. • A record number of participants came to the STEM Education Our sincere thanks to outgoing board members Greg Anklam, Jim Fla- and School Leadership Conferences. More than 370 educators herty, Donna Harris and Doug Jaeger for their service and active commit- and school leaders attended these two events during August ment to a strong and vibrant sector. and September. We welcome your voice, support and assistance to further raise the ca- • Nearly 150 schools participated in the 2015 Statewide Census pacity of independent and private schools in our state. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Dear Friends

Catholic Community FOUNDATION OF MINNESOTA onlyCOMMUNION IN THE MIDST OF CRISIS together ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Dear Friends, None of us will forget 2020 anytime soon. The pandemic, together with the social unrest in the wake of George Floyd’s unjust death, have taken a heavy toll. At the same time, I’m very proud of how our Catholic community has responded. In the midst of dual crises, in a time of fear and uncertainty, we have come together to help our neighbors and support Catholic organizations. Only together can we achieve success, as Archbishop Hebda says, “On our own, there’s little that we’re able to accomplish. It’s only with collaboration, involving the thinking and generosity of many folks that we’re able to put together a successful plan.” The Catholic Community Foundation of Minnesota (CCF) has never been better prepared to meet the challenges of the moment. Within days of the suspension of public Masses in March, CCF established onlyCOMMUNION IN THE MIDST OF CRISIS the Minnesota Catholic Relief Fund. Immediately, hundreds of generous people made extraordinary donations to support our local Catholic community. Shortly thereafter, CCF began deploying monies to parishes and schools in urgent need. This was all possible because CCF had the operational and relational infrastructure in place to act swiftly: the connections, the trust, the expertise, and the overwhelming support of our donors. CCF has proven it’s just as capable of serving the long-term needs of our Catholic community. together Through our Legacy Fund and a variety of endowments, individuals can support Catholic ministries in perpetuity, while parishes partner with CCF to safeguard their long-term financial stability. -

Edited by Conor Hill, Kent Lasnoski, Matthew Sherman, John Sikorski and Matthew Whelan

VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2017 NEW WINE, NEW WINESKINS: PERSPECTIVES OF YOUNG MORAL THEOLOGIANS Edited by Conor Hill, Kent Lasnoski, Matthew Sherman, John Sikorski and Matthew Whelan Journal of Moral Theology is published semiannually, with issues in January and June. Our mission is to publish scholarly articles in the field of Catholic moral theology, as well as theological treatments of related topics in philosophy, economics, political philosophy, and psychology. Articles published in the Journal of Moral Theology undergo at least two double blind peer reviews. Authors are asked to submit articles electronically to [email protected]. Submissions should be prepared for blind review. Microsoft Word format preferred. The editors assume that submissions are not being simultaneously considered for publication in another venue. Journal of Moral Theology is indexed in the ATLA Catholic Periodical and Literature Index® (CPLI®), a product of the American Theological Library Association. Email: [email protected], www: http://www.atla.com. ISSN 2166-2851 (print) ISSN 2166-2118 (online) Journal of Moral Theology is published by Mount St. Mary’s University, 16300 Old Emmitsburg Road, Emmitsburg, MD 21727. Copyright© 2017 individual authors and Mount St. Mary’s University. All rights reserved. EDITOR EMERITUS AND UNIVERSITY LIAISON David M. McCarthy, Mount St. Mary’s University EDITOR Jason King, Saint Vincent College ASSOCIATE EDITOR William J. Collinge, Mount St. Mary’s University MANAGING EDITOR Kathy Criasia, Mount St. Mary’s University EDITORIAL BOARD Melanie Barrett, University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary Jana M. Bennett, University of Dayton Mara Brecht, St. Norbert College Jim Caccamo, St. -

Foundation of Minnesota

Catholic Community FOUNDATION OF MINNESOTA table of plenty CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF COLLECTIVE CATHOLIC LEADERSHIP IN GIVING ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Dear Friends, As we celebrate our 25th anniversary, I’m humbled by the outpouring of joy from our Catholic community. At $358 million in assets, the Catholic Community Foundation of Minnesota (CCF) is the largest of its kind in the nation, but we don’t believe that’s the true measure of our success. From the beginning, CCF has engaged philanthropic Catholics and stewarded their charitable giving. As the years have passed, we’ve accumulated more than assets. We’ve accumulated table of plenty valuable insights into the resources and needs of our community. Last year, we invested those insights into new initiatives that have yielded significant returns. We were inspired to share what At the table of plenty, we share both our needs and our gifts and discover they fulfill one another. we’ve learned at three Giving Insights forums. We experienced the joy of satisfying a thirst for connection that many of us didn’t realize we had. I’m happy to share the series continues today. Just as when Jesus fed the 5,000 with five loaves and two fish, we find there is plenty of room, plenty of need, and plenty to share. There is enough. For the past 25 years, CCF has set the table and invited We made our first impact investments, leveraging our ability as an investor to advance the our community to take part. Come to the table of plenty. common good. -

The Defendant (Autumn, 2016)

The DEFENDANT Newsletter of the Australian Chesterton Society Vol. 23 No. 2 Autumn 2016 Issue No. 89 powerfully to such varied peoples on ‘I have found that virtually every continent. Chesterton’s humanity is not A Global wisdom is of such universal value that his incidentally engaged, writings wear the clothes of every culture. but eternally and Chesterton systematically engaged, by Karl Schmude One of the most remarkable signs of this phenomenon is the deep interest that was in throwing gold into the One of the fascinating features of the revival shown by the Argentinian writer, Jorge gutter and diamonds into of interest in Chesterton is its international Luis Borges (1899-1986). Borges admired the sea. ; therefore I scope. Chesterton greatly. He translated some of have imagined that the his works into Spanish, and he wrote an main business of man, The extent of his appeal is truly worldwide illuminating essay on Chesterton which however humble, is – European (embracing such countries as appeared in a collection of essays entitled defence. I have conceived France, Spain, Italy and Poland), North and Other Inquisitions: 1937-1952. South America, Asia, Africa, and of course that a defendant is chiefly Australia. Despite their many differences of experience required when worldlings and outlook, Chesterton and Borges shared despise the world – that It is of striking importance that Chesterton certain interests, including a fondness for a counsel for the defence should exert such a global appeal. In keeping detective stories and a profound and would not have been out with his great size, he has become, in the 21st penetrating awareness of mystery and of place in the terrible day century, an author of global dimensions! allegory. -

Regular Meeting of the School Board Eisenhower Community Center Boardroom August 17, 2021 — 7 P.M

Regular Meeting of the School Board Eisenhower Community Center Boardroom August 17, 2021 — 7 p.m. ORDER OF BUSINESS I. CALL TO ORDER II. OPEN AGENDA A. Public Comment on Agenda Items The Hopkins School Board believes that hearing from our community members is crucial for implementing Vision 2031. If you wish to contact the Board via email instead of publicly commenting at a meeting, please use School- [email protected]. Public comment will be received both in person and through voicemail. Voicemail: If you wish to record a public comment to be played during the next School Board meeting, please call 952-988-4191 to hear a message with instructions from the Board Chair and to leave your public comment as a voicemail. Indicate at the beginning of the voicemail the agenda item you are commenting on, or if your comment is related to a topic not on the agenda. Please leave your message before 4:00 p.m. on the day of the School Board meeting in order to have your voicemail played during the public comment portion of the meeting. In Person: Please fill out a public comment card (located in the back of the Board Room) and hand it to the Board Chair before the meeting begins. Indicate on the card which agenda item you will be commenting on, or if you will be speaking on a topic that is not on the agenda. The Board Chair will invite you to the table to give your comment at the appropriate time. The Board will host two public comment periods per meeting. -

2016 GIVING REPORT As We Reflect on the Success of 2016 and Look Ahead, We Are Grateful for the Collective Efforts of All Who Helped Cultivate Generosity This Year

2016 GIVING REPORT As we reflect on the success of 2016 and look ahead, we are grateful for the collective efforts of all who helped cultivate generosity this year. This year our donors gave 11,000 grants—a record!—to 2,349 nonprofits. And we opened 154 new donor accounts, which helps further expand our reach. With more than $1 billion in assets, we are now the 15th largest community foundation in the country, according to CF Insights. While these numbers are impressive, our biggest successes are reflected in the relationships we continue to build across our community. In 2016, we worked to deepen our impact throughout the region. We launched The Landscape, a community indicator project that uses publicly available data to gage how the Omaha metro is faring in six areas community life. This project reaffirms our commitment to meeting the community’s greatest needs, while expanding the breadth and depth of knowledge we offer. The Landscape is a space where each of us can dig deeper and learn about this community beyond our own unique experience; our hope is that this project helps inform our own work, and the efforts of our many partners and collaborators across the Omaha-Council Bluffs region. Each and every day these partners—our board, staff, the area’s nonprofit sector, and our family of donors—are driven to make this community a better place for all. Together we seek to inspire philanthropy that’s both big and small—whether it’s a new $10 donation given during Omaha Gives!, a leader influenced through our Nonprofit Capacity Building Program, or a donor that witnesses the tangible impact of their substantial gift. -

Saintgilbert?

“The skeptics have no philosophy of life because they have no philosophy of death.” —G.K. chesTERTON VOL NO 17 1 $550 SEPT/OCT 2013 . Saint Gilbert?SEE PAGE 12 . rton te So es l h u C t i Order the American e o n h T nd E nd d e 32 s Chesterton Society u 32 l c E a t g io in n th , E y co ver Annual Conference Audio nomics & E QTY. Dale Ahlquist, President of the American QTY. Carl Hasler, Professor of Philosophy, QTY. Kerry MacArthur, Professor of English, Chesterton Society Collin College University of St. Thomas “The Three Es” (Includes “Chesterton and Wendell “How G.K. Chesterton Dale’s exciting announce- Berry: Economy of Scale Invented Postmodern ment about GKC’s Cause) and the Human Factor” Literature” QTY. Chuck Chalberg as G.K. Chesterton QTY. Joseph Pearce, Writer-in-Residence and QTY. WIlliam Fahey, President of Thomas Professor of Humanities at Thomas More More College of the Liberal Arts Eugenics and Other Evils College; Co-Editor of St. Austin Review “Beyond an Outline: The “Chesterton and The Hobbit” QTY. James Woodruff, Teacher of Forgotten Political Writings Mathematics, Worcester Academy of Belloc and Chesterton” QTY. Kevin O’Brien’ s Theatre of the Word “Chesterton & Macaulay: two Incorporated presents histories, two QTY. Aaron Friar (converted to Eastern Orthodoxy as a result of reading a book Englands” “Socrates Meets Jesus” By Peter Kreeft called Orthodoxy) QTY. Pasquale Accardo, Author and Professor “Chesterton and of Pediatric Medicine QTY. Peter Kreeft, Author and Professor of Eastern Orthodoxy” “Shakespeare’s Most Philosophy, Boston College Catholic Play” The Philosophy of DVD bundle: $120.00 G.K. -

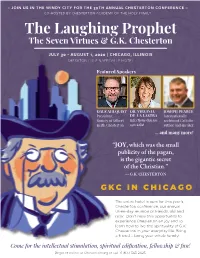

The Laughing Prophet the Seven Virtues & G.K

– JOIN US IN THE WINDY CITY FOR THE 39TH ANNUAL CHESTERTON CONFERENCE – CO-HOSTED BY CHESTERTON ACADEMY OF THE HOLY FAMILY The Laughing Prophet The Seven Virtues & G.K. Chesterton JULY 30 - AUGUST 1, 2020 | CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SHERATON LISLE NAPERVILLE HOTEL Featured Speakers DALE AHLQUIST DR. VIRGINIA JOSEPH PEARCE President, DE LA LASTRA Internationally Society of Gilbert Infectious disease acclaimed Catholic Keith Chesterton specialist author and speaker ... and many more! “JOY, which was the small publicity of the pagan, is the gigantic secret of the Christian.” — G.K. CHESTERTON GKC IN CHICAGO The entire hotel is ours for this year’s Chesterton conference, our annual three-day reunion of friends, old and new. Don’t miss this opportunity to experience Chestertonian joy and to learn how to live the spirituality of G.K. Chesterton in your everyday life. Bring a friend ... bring your whole family! Come for the intellectual stimulation, spiritual edification, fellowship & fun! Register online at Chesterton.org or call +1-800-343-2425. 39th Annual Chesterton Conference Conference Schedule The Laughing Prophet | July 30-Aug 1 DAY ONE DAY TWO THURSDAY, JULY 30 FRIDAY, JULY 31 Check-In & Registration 7:15AM – Rosary followed by Daily Mass (7:30AM) 7:30AM – Breakfast service begins 2:00PM – Registration and Vendor Tables Open Morning Session 3:45PM – Rosary 4:00PM – Opening Mass 9:00AM – Paging Dr. Chesterton 5:00PM – Welcome Reception, White Horse Reception Dr. Virginia de la Lastra, University of Chile G.K. Chesterton Traveling Museum Open How a medical doctor of infectious disease sneaks the giant G.K. Chesterton into the sciences in unexpected ways. -

Faith Reason Culture of Life Order the Conference Talks from the 2011 St

Volume 14 Number 8, July/August 2011 $5.50 “The one thing that is never taught by any chance in the atmosphere of public schools is this: that there is a whole truth of things, and that in knowing it and speaking it we are happy.” —G.K. Chesterton Faith Reason Culture of Life Order the Conference talks from the 2011 St. Louis, Missouri Conference! Or download them from www.chesterton.org the american chesterton society qty. Dale ahlquist (President of the qty. Dr. pasquale aCCarDo (Professor of qty. leah Darrow (Former contestant on the American Chesterton Society) Developmental Research in Pediatrics reality TV show America’s Next Top Model) at Virginia Commonwealth University, The Poetic Prophet, and author of several books on medicine, The Mysticism of Modesty The Prophetic Poet literature, and detective fiction) and the Poetry of Purity qty. Christopher CheCK (Executive Vice The Christian Epic of qty. Dale ahlquist President of the Rockford Institute) Freedom – Chesterton’s The Chesterton and Lepanto: The Battle Ballad of the White Horse Father Brown and the Poem reDD Griffin (Instructor at Triton qty. qty. eleanor bourG niCholson College and founding director of the qty. Carl hasler (Professor of (Assistant executive editor of Dappled Philosophy at Collin College) Ernest Hemingway Foundation) Things and assistant editor for the Saint Austin Review, and editor of the Chesterton: A Battling for Elfland: Ignatius Critical Edition of Dracula) Franciscan Thomist? Chesterton and William Butler Yeats Damned Romantics: qty. robert Moore-JuMonville (Professor Chesterton, Shelley, Poetry, of Religion at Spring Arbor University qty. John C. “ChuCK” ChalberG (Actor and columnist for Gilbert Magazine) who specializes in G.K. -

(PPP) Loans > $150000 for Minnesota Schools

Payroll Protection Program (PPP) Loans > $150,000 for Minnesota Schools: Using NAICS Code 611110 Schools Sorted from Most to Least: Loan Amounts Reported by Range Charter Students Jobs Amount Amount Amount # School Name FY20 Retained Low /adm High /adm Midpoint /adm Type? All NAICS 611110 48,464 9,619 63,850,000 $1,317 154,400,000 $3,186 109,125,000 $2,252 Charter Schools Total Listed 20,683 3,272 19,350,000 $936 48,000,000 $2,321 33,675,000 $1,628 c=charter Nonpublic Schools Total Listed 27,781 5,534 40,800,000 $1,469 96,850,000 $3,486 68,825,000 $2,477 n=nonpublic Others using 611110 code 0 813 3,700,000 9,550,000 6,625,000 other Charter Schools 4017 Minnesota Transitions Charter School 3,749 226 2,000,000 $533 5,000,000 $1,334 3,500,000 $934 c 4183 Lionsgate Academy 300 239 2,000,000 $6,667 5,000,000 $16,667 3,500,000 $11,667 c 4098 Nova Classical Academy 994 132 1,000,000 $1,006 2,000,000 $2,012 1,500,000 $1,509 c 4126 Prairie Seeds Academy 780 99 1,000,000 $1,282 2,000,000 $2,564 1,500,000 $1,923 c 4181 Community School Of Excellence 1,384 153 1,000,000 $723 2,000,000 $1,445 1,500,000 $1,084 c 4191 Kipp Minnesota 536 101 1,000,000 $1,866 2,000,000 $3,731 1,500,000 $2,799 c 4192 Best Academy 760 153 1,000,000 $1,316 2,000,000 $2,632 1,500,000 $1,974 c 4007 Minnesota New Country School 216 46 350,000 $1,620 1,000,000 $4,630 675,000 $3,125 c 4025 Cyber Village Academy, Inc.