December 2019 Trade Bulletin.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks' Risk in China

In the Shadow of Banks: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks’ Risk in China* Viral V. Acharya Jun “QJ” Qian Zhishu Yang New York University, and Shanghai Adv. Inst. of Finance School of Economics and Mgmt. Reserve Bank of India Shanghai Jiao Tong University Tsinghua University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] This Draft: February 10, 2017 Abstract To support China’s massive stimulus plan in response to the global financial crisis in 2008, large state-owned banks pumped huge volume of new loans into the economy and also grew more aggressive in the deposit markets. The extent of supporting the plan was different across the ‘Big Four’ banks, creating a plausibly exogenous shock in the local deposit market to small and medium-sized banks (SMBs) facing differential competition from the Big Four banks. We find that SMBs significantly increased shadow banking activities after 2008, most notably by issuing wealth management products (WMPs). The scale of issuance is greater for banks that are more constrained by on-balance sheet lending and face greater competition in the deposit market from local branches of the most rapidly expanding big bank. The WMPs impose a substantial rollover risk for issuers when they mature, as reflected by the yields on new products, the issuers’ behavior in the inter-bank market, and the adverse effect on stock prices following a credit crunch. Overall, the swift rise of shadow banking in China seems to be triggered by the stimulus plan and has contributed to the greater fragility of the banking system. -

Harbin Bank Co., Ltd. 哈爾濱銀行股份有限公司* (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 6138)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Harbin Bank Co., Ltd. 哈爾濱銀行股份有限公司* (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 6138) 2019 ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the “Board”) of Harbin Bank Co., Ltd. (the “Bank”) is pleased to announce the audited annual results of the Bank and its subsidiaries (the “Group”) for the year ended 31 December 2019. This results announcement, containing the full text of the 2019 Annual Report of the Bank, complies with the relevant content requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to preliminary announcements of annual results. The annual financial statements of the Group for the year ended 31 December 2019 have been audited by Ernst & Young in accordance with International Standard on Review Engagements. Such annual results have also been reviewed by the Board and the Audit Committee of the Bank. Unless otherwise stated, financial data of the Group are presented in Renminbi. This results announcement is published on the websites of the Bank (www.hrbb.com.cn) and HKExnews (www.hkexnews.hk). The printed version of the 2019 Annual Report of the Bank will be dispatched to the holders of H shares of the Bank and available for viewing on the above websites in April 2020. -

HARBIN BANK CO., LTD. (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) Stock Code: 6138

HARBIN BANK CO., LTD. (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code: 6138 2020 INTERIM REPORT Harbin Bank Co., Ltd. Contents Interim Report 2020 Definitions 2 Company Profile 3 Summary of Accounting Data and Financial Indicators 7 Management Discussion and Analysis 9 Changes in Share Capital and Information on Shareholders 73 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Employees 78 Important Events 84 Organisation Chart 90 Financial Statements 91 Documents for Inspection 188 The Company holds the Finance Permit No. B0306H223010001 approved by the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission and has obtained the Business License (Unified Social Credit Code: 912301001275921118) approved by the Market Supervision and Administration Bureau of Harbin. The Company is not an authorised institution within the meaning of the Hong Kong Banking Ordinance (Chapter 155 of the Laws of Hong Kong), not subject to the supervision of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, and not authorised to carry on banking/deposit-taking business in Hong Kong. Denitions In this report, unless the context otherwise requires, the following terms shall have the meanings set out below. “Articles of Association” the Articles of Association of Harbin Bank Co., Ltd. “Board” or “Board of Directors” the board of directors of the Company “Board of Supervisors” the board of supervisors of the Company “CBIRC”/”CBRC” the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission/China Banking Regulatory Commission (before 17 March -

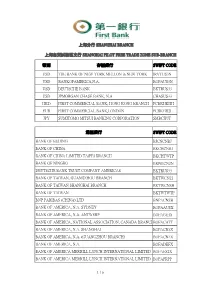

1 / 6 幣別 存匯銀行 Swift Code Usd the Bank of New York

上海分行 SHANGHAI BRANCH 上海自貿試驗區支行 SHANGHAI PILOT FREE TRADE ZONE SUB-BRANCH 幣別 存匯銀行 SWIFT CODE USD THE BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON in NEW YORK IRVTUS3N USD BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. BOFAUS3N USD DEUTSCHE BANK BKTRUS33 USD JPMORGAN CHASE BANK, N.A CHASUS33 HKD FIRST COMMERCIAL BANK, HONG KONG BRANCH FCBKHKHH EUR FIRST COMMERCIAL BANK,LONDON FCBKGB2L JPY SUMITOMO MITSUI BANKING CORPORATION SMBCJPJT 通匯銀行 SWIFT CODE BANK OF BEIJING BJCNCNBJ BANK OF CHINA BKCHCNBJ BANK OF CHINA LIMITED TAIPEI BRANCH BKCHTWTP BANK OF NINGBO BKNBCN2N DEUTSCHE BANK TRUST COMPANY AMERICAS BKTRUS33 BANK OF TAIWAN, GUANGZHOU BRANCH BKTWCN22 BANK OF TAIWAN SHANGHAI BRANCH BKTWCNSH BANK OF TAIWAN BKTWTWTP BNP PARIBAS (CHINA) LTD BNPACNSH BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. SYDNEY BOFAAUSX BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. ANTWERP BOFABE3X BANK OF AMERICA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, CANADA BRANCHBOFACATT BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. SHANGHAI BOFACN3X BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. (GUANGZHOU BRANCH) BOFACN4X BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. BOFADEFX BANK OF AMERICA MERRILL LYNCH INTERNATIONAL LIMITED BOFAES2X BANK OF AMERICA MERRILL LYNCH INTERNATIONAL LIMITED BOFAFRPP 1 / 6 通匯銀行 SWIFT CODE BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. LONDON BOFAGB22 BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. ATHENS BOFAGR2X BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. HONG KONG BOFAHKHX BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. JAKARTA BRANCH BOFAID2X BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. MUMBAI BOFAIN4X BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. BOFAIT2X BANK OF AMERICA, TOKYO BOFAJPJX BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. SEOUL BRANCH BOFAKR2X BANK OF AMERICA, MALAYSIA BERHAD BOFAMY2X BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. AMSTERDAM BOFANLNX BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. MANILA BOFAPH2X BANK OF AMERICA, N.A. SINGAPORE BOFASG2X BANK OF AMERICA (SINGAPORE) LTD. -

Banking Newsletter

September 2017 Banking Newsletter Review and Outlook of China’s Banking Industry for the First Half of 2017 www.pwccn.com Editorial Team Editor-in-Chief:Vivian Ma Deputy Editor-in-Chief:Haiping Tang, Carly Guan Members of the editorial team: Cynthia Chen, Jeff Deng, Carly Guan, Tina Lu, Haiping Tang (in alphabetical order of last names) Advisory Board Jimmy Leung, Margarita Ho, Richard Zhu, David Wu, Yuqing Guo, Jianping Wang, William Yung, Mary Wong, Michael Hu, James Tam, Raymond Poon About this newsletter The Banking Newsletter, PwC’s analysis of China’s listed banks and the wider industry, is now in its 32nd edition. Over the past one year there have been several IPOs for small-and-medium-sized banks, increasing the universe of listed banks in China. This analysis covers 39 A-share and/or H-share listed banks that have released their 2017 first half results. Those banks are categorized into four groups as defined by the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC): Large Commercial Joint-Stock Commercial City Commercial Banks Rural Commercial Banks Banks (6) Banks (9) (16) (8) Industrial and Commercial Chongqing Rural Commercial Bank Bank of China (ICBC) China Industrial Bank (CIB) Bank of Beijing (Beijing) (CQRCB) China Construction Bank China Merchants Bank (CMB) Bank of Shanghai (Shanghai) (CCB) Guangzhou Rural Commercial Bank SPD Bank (SPDB) Bank of Hangzhou (Hangzhou) Agricultural Bank of China (GZRCB) (ABC) China Minsheng Bank Corporation Bank of Jiangsu (Jiangsu) (CMBC) Jiutai Rural Commercial Bank Bank of China (BOC) Bank of -

The Architecture of Harbin's First Banking Institutions. Fujiadian District

IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering PAPER • OPEN ACCESS The Architecture of Harbin’s First Banking Institutions. Fujiadian District To cite this article: M E Bazilevich and A A Kim 2021 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 1079 022045 View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 170.106.202.226 on 24/09/2021 at 23:56 International Science and Technology Conference (FarEastСon 2020) IOP Publishing IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 1079 (2021) 022045 doi:10.1088/1757-899X/1079/2/022045 The Architecture of Harbin’s First Banking Institutions. Fujiadian District M E Bazilevich1,a and A A Kim1,b 1Department of Architecture and Urbanistics, Institute of Architecture and Design, Pacific National University, 136, Tihookeanskaya St., Khabarovsk, 680035, Russia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. The article is devoted to the architecture of the first banking institutions of one of the largest historic districts of Harbin: Fujiadian (now Daowai). A brief historical overview of the history of formation and development of the district is given. The buildings of banking institutions that have been preserved on its territory have been identified. As a result, the main directions of development of this layer of Harbin architecture, associated with the spread of “Chinese Baroque” and strict Neoclassicism in the architecture of the city, were determined. The architectural features of particular bank buildings are considered and their importance in the formation of the historical and architectural environment of Harbin is shown. 1. Introduction The history of Harbin is closely related to the construction of the China-East Railway (CER). -

Banknotes Week Ended 14 March 2014

NEWSLETTER FINANCIAL SERVICES Banknotes Week ended 14 March 2014 Title KPMG China’s weekly banking news summary This publication is a summary of publicly reported information, the accuracy of which has not been verified by KPMG. Final results for the year ended 31 December 2013 In the news Chong Hing Bank China CITIC Bank – Net profit after tax rose 2.6% to HKD 557 million. China Minsheng Bank – Net interest income rose 21.2% to HKD 1.01 billion, while the net interest margin increased 16 basis points to 1.26%. Chong Hing Bank – Net fee and commission income rose 10.9% to HKD 210 million. Harbin Bank – The basic earnings per share increased 2.6% to HKD 1.28. Mizuho Bank – Tier 1 capital ratio increased to 10.82% at the end of 2013. People’s Bank of China – A final dividend of HKD 0.33 per share was proposed for 2013. Ping An Bank Qingdao Rural Commercial Bank China Minsheng Bank signs agreement with China Taiping – China Minsheng Ta Chong Bank Banking Corp., Ltd has signed a partnership agreement with China Taiping UBS Insurance Group Co., Ltd to promote the development of the insurance agency and pension insurance business, among others. Harbin Bank approved to list on HKSE – The Hong Kong Stock Exchange has granted listing approval to China-based Harbin Bank for its USD 1 billion initial public offering. Mizuho Bank opens sub-branch in Shanghai Free-trade Zone – Mizuho Bank (China), Limited has opened a sub-branch in the Shanghai Free-trade Zone. Ping An sells RMB 9 billion worth of bonds – Shenzhen-based Ping An Bank has issued RMB 9 billion worth of 10-year RMB-denominated bonds, with an interest rate of 6.8 percent. -

Harbin Bank Co., Ltd. 哈爾濱銀行股份有限公司* (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 6138)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Harbin Bank Co., Ltd. 哈爾濱銀行股份有限公司* (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 6138) 2015 ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the “Board”) of Harbin Bank Co., Ltd. (the “Bank”) is pleased to announce the audited annual results of the Bank and its subsidiaries (the “Group”) for the year ended 31 December 2015. This results announcement, containing the full text of the 2015 Annual Report of the Bank, complies with the relevant content requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to preliminary announcements of annual results. The annual financial statements of the Group for the year ended 31 December 2015 have been audited by Ernst & Young in accordance with International Standard on Review Engagements. Such annual results have also been reviewed by the Board and the audit committee of the Bank. Unless otherwise stated, financial data of the Group are presented in Renminbi. This results announcement is published on the websites of the Bank (www.hrbb.com.cn) and HKExnews (www.hkexnews.hk). The printed version of the 2015 Annual Report of the Bank will be dispatched to the holders of H shares of the Bank and available for viewing on the above websites in April 2016. -

China's Banking System: Issues for Congress

China’s Banking System: Issues for Congress Michael F. Martin Specialist in Asian Affairs February 20, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42380 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress China’s Banking System: Issues for Congress Summary China’s banking system has been gradually transformed from a centralized, government-owned and government-controlled provider of loans into an increasingly competitive market in which different types of banks, including several U.S. banks, strive to provide a variety of financial services. Only three banks in China remain fully government-owned; most banks have been transformed into mixed ownership entities in which the central or local government may or may not be a major equity holder in the bank. The main goal of China’s financial reforms has been to make its banks more commercially driven in their operations. However, China’s central government continues to wield significant influence over the operations of many Chinese banks, primarily through the activities of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC), and the Ministry of Finance (MOF). In addition, local government officials often attempt to influence the operations of Chinese banks. Despite the financial reforms, allegations of various forms of unfair or inappropriate competition have been leveled against China’s current banking system. Some observers maintain that China’s banks remain under government-control, and that the government is using the banks to provide inappropriate subsidies and assistance to selected Chinese companies. Others claim that Chinese banks are being afforded preferential treatment by the Chinese government, given them an unfair competitive advantage over foreign banks trying to enter China’s financial markets. -

1 Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on “China's Quest for Capital: Motivations

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on “China’s Quest for Capital: Motivations, Methods, and Implications” Dinny McMahon Author of “China’s Great Wall of Debt: Shadow Banks, Ghost Cities, Massive Loans, and the End of the Chinese Miracle.” January 23, 2020 In the years following the Global Financial Crisis, China pursued a credit expansion unprecedented in its size and speed. Not all of the debt was well spent, resulting in a build-up of industrial overcapacity, empty housing, and underutilized infrastructure. China’s financial system is now dealing with the fallout of that waste and excess. Since 2016, China’s banks have accelerated their disposal of nonperforming loans (NPLs). Nonetheless, the pace of disposals has remained slow and measured, a deliberate decision on Beijing’s part to minimize economic disruption by spreading out the cost of resolving bad loans over an extended period of time. The approach hasn’t been without merit. Banks have been able to accelerate the pace of NPL disposal while relying primarily on retained earnings to replenish capital eroded by write-offs. To the extent that banks have needed to sell bonds and equity to augment their capital, the market has proven up to task of absorbing the demand. However, China may have already reached the limitations of that approach. In 2019, the government intervened directly to prop up five of China’s 50 biggest banks. It’s feasible to think there will be further interventions in the years ahead. The chairman of China’s sovereign wealth fund recently said as much, noting that as the economy slows, the failure of financial institutions will become “a fact of life”.1 Certainly, it seems likely that the banking sectors’ need for new capital will accelerate in the years ahead. -

UFJ China Correspondents.Xlsx

Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ; Overseas Correspondents (CHINA, TAIWAN, HONG KONG) City Bank Name ANQING BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO., LTD. ANSHAN BANK OF CHINA LIMITED BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO., LTD. INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED BAODING INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED BAOTOU BANK OF CHINA LIMITED BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO., LTD. BEIHAI BANK OF CHINA LIMITED BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO., LTD. BEIJING AGRICULTURAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT BANK OF CHINA AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANK (CHINA) COMPANY LIMITED BANK OF AMERICA N.A. BANK OF BEIJING CO., LTD BANK OF CHINA LIMITED BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO., LTD. BANK OF MONTREAL (CHINA) CO. LTD. BANK OF TOKYO-MITSUBISHI UFJ (CHINA), LTD. BNP PARIBAS (CHINA) LIMITED CHINA CITIC BANK CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORPORATION CHINA DEVELOPMENT BANK CORPORATION CHINA EVERBRIGHT BANK CHINA MERCHANTS BANK CO. LTD. CHINA MINSHENG BANKING CORPORATION LTD CITIBANK (CHINA) CO., LTD. DBS BANK (CHINA) LIMTIED GUANGDONG DEVELOPMENT BANK HANA BANK (CHINA) COMPANY LIMITED HSBC BANK (CHINA) COMPANY LIMITED HUA XIA BANK INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED INDUSTRIAL BANK CO., LTD. JPMORGAN CHASE BANK (CHINA) COMPANY LIMITED KEB BANK (CHINA) CO., LTD. MIZUHO CORPORATE BANK (CHINA), LIMITED PEOPLE'S BANK OF CHINA/STATE ADMINISTRATION OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE RAIFFEISEN BANK INTERNATIONAL AG ROAYL BANK OF CANADA SHANGHAI PUDONG DEVELOPMENT BANK SHENZHEN DEVELOPMENT BANK CO. LTD. SHINHAN BANK (CHINA) LIMITED SOCIETE GENERALE (CHINA) LIMITED STANDARD CHARTERED BANK (CHINA) LIMITED STANDARD CHARTERED BANK (CHINA) LIMITED SUMITOMO MITSUI BANKING CORPORATION (CHINA) LIMITED THE BANK OF EAST ASIA (CHINA) LIMITED THE EXPORT-IMPORT BANK OF CHINA THE KOREA DEVELOPMENT BANK THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND (CHINA) CO., LTD. -

China Consumer Finance Market Insights

China Consumer Finance Market Insights Working Group of CFA China Shanghai CrowdResearch Project* January 2018 *Members of working Group: Chen Yan, CFA, Gu Yuan, CFA, Li Chen, CFA, Wang Yingren, CFA, Ying Yi, CFA, Zhang Shuguang, CFA, Zhao Yang, CFA 1| Page Table of Contents Research Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter I Consumers and Consumer Financial Behavior ............................................................................. 6 Chapter II Summary of China's Consumer Finance Industry Development ................................................. 6 Section I China Consumer Finance Development Events .................................................................... 6 Section II Development of China's Consumer Finance Policies .......................................................... 8 Section III History of Foreign Consumer Finance ............................................................................. 10 Chapter III Current Situation of China's Consumer Finance Market ......................................................... 15 Section I Industry Chain of Consumer Finance ................................................................................. 15 Section II Consumer Finance Companies .........................................................................................