Kant with Lacan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Screen Romantic Genius.Pdf MUSIC AND

“WHAT ONE MAN CAN INVENT, ANOTHER CAN DISCOVER” MUSIC AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF SHERLOCK HOLMES FROM LITERARY GENTLEMAN DETECTIVE TO ON-SCREEN ROMANTIC GENIUS By Emily Michelle Baumgart A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Musicology – Master of Arts 2015 ABSTRACT “WHAT ONE MAN CAN INVENT, ANOTHER CAN DISCOVER” MUSIC AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF SHERLOCK HOLMES FROM LITERARY GENTLEMAN DETECTIVE TO ON-SCREEN ROMANTIC GENIUS By Emily Michelle Baumgart Arguably one of the most famous literary characters of all time, Sherlock Holmes has appeared in numerous forms of media since his inception in 1887. With the recent growth of on-screen adaptations in both film and serial television forms, there is much new material to be analyzed and discussed. However, recent adaptations have begun exploring new reimaginings of Holmes, discarding his beginnings as the Victorian Gentleman Detective to create a much more flawed and multi-faceted character. Using Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original work as a reference point, this study explores how recent adaptors use both Holmes’s diegetic violin performance and extra-diegetic music. Not only does music in these screen adaptations take the role of narrative agent, it moreover serves to place the character of Holmes into the Romantic Genius archetype. Copyright by EMILY MICHELLE BAUMGART 2015 .ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am incredibly grateful to my advisor Dr. Kevin Bartig for his expertise, guidance, patience and good humor while helping me complete this document. Thank you also to my committee members Dr. Joanna Bosse and Dr. Michael Largey for their new perspectives and ideas. -

Theory and Interpretation of Narrative) Includes Bibliographical References and Index

Theory and In T e r p r e Tati o n o f n a r r ati v e James Phelan and Peter J. rabinowitz, series editors Postclassical Narratology Approaches and Analyses edited by JaN alber aNd MoNika FluderNik T h e O h i O S T a T e U n i v e r S i T y P r e ss / C O l U m b us Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Postclassical narratology : approaches and analyses / edited by Jan Alber and Monika Fludernik. p. cm. — (Theory and interpretation of narrative) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-5175-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-5175-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1142-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1142-9 (cloth : alk. paper) [etc.] 1. Narration (Rhetoric) I. Alber, Jan, 1973– II. Fludernik, Monika. III. Series: Theory and interpretation of narrative series. PN212.P67 2010 808—dc22 2010009305 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1142-7) Paper (ISBN 978-0-8142-5175-1) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9241-9) Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Sabon Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction Jan alber and monika Fludernik 1 Part i. -

Footnotes in Fiction: a Rhetorical Approach

FOOTNOTES IN FICTION: A RHETORICAL APPROACH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Edward J. Maloney, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor James Phelan, Adviser Professor Morris Beja ________________________ Adviser Professor Brian McHale English Graduate Program Copyright by Edward J. Maloney 2005 ABSTRACT This study explores the use of footnotes in fictional narratives. Footnotes and endnotes fall under the category of what Gérard Genette has labeled paratexts, or the elements that sit above or external to the text of the story. In some narratives, however, notes and other paratexts are incorporated into the story as part of the internal narrative frame. I call this particular type of paratext an artificial paratext. Much like traditional paratexts, artificial paratexts are often seen as ancillary to the text. However, artificial paratexts can play a significant role in the narrative dynamic by extending the boundaries of the narrative frame, introducing new heuristic models for interpretation, and offering alternative narrative threads for the reader to unravel. In addition, artificial paratexts provide a useful lens through which to explore current theories of narrative progression, character development, voice, and reliability. In the first chapter, I develop a typology of paratexts, showing that paratexts have been used to deliver factual information, interpretive or analytical glosses, and discursive narratives in their own right. Paratexts can originate from a number of possible sources, including allographic sources (editors, translators, publishers) and autographic sources— the author, writing as author, fictitious editor, or one or more of the narrators. -

Legal Narratology (Reviewing Law's Stories: Narrative and Rhetoric In

REVIEWS Legal Narratology RichardA Posnert Law's Stories: Narrativeand Rhetoric in the Law. Peter Brooks and Paul Gewirtz, eds. Yale University Press, 1996. Pp v, 290. The law and literature movement has evolved to a point at which it comprises a number of subdisciplines. One of the newer ones--call it "legal narratology"-is concerned with the story elements in law and legal scholarship. A major symposium on le- gal narratology was held at the Yale Law School in 1995, and Law's Stories is a compilation of essays and comments given at the symposium. The book is not definitive or even comprehen- sive. Not all bases are touched, and a number of leading practi- tioners of legal narratology did not participate. But it is about as good a place as any to start if you want to understand and evalu- ate the new field. The papers in the volume span a wide range, covering the narrative elements in legal scholarship, trials, sen- tencing hearings, confessions, and judicial opinions. The editors, Peter Brooks and Paul Gewirtz, a professor of comparative litera- ture and a professor of law respectively, have each written a lu- cid and informative introduction. The book is well edited and highly readable-and so well balanced that, as we shall see, it makes the reader wonder just how bright the future of legal nar- ratology is. A story, or, better, a narrative (because "story" suggests a short narrative), is a true or fictional account of a sequence of t Chief Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit; Senior Lec- turer in Law, The University of Chicago. -

Anatomy of Criticism with a New Foreword by Harold Bloom ANATOMY of CRITICISM

Anatomy of Criticism With a new foreword by Harold Bloom ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Four Essays Anatomy of Criticism FOUR ESSAYS With a Foreword by Harold Bloom NORTHROP FRYE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY Copyright © 1957, by Princeton University Press All Rights Reserved L.C. Card No. 56-8380 ISBN 0-691-06999-9 (paperback edn.) ISBN 0-691-06004-5 (hardcover edn.) Fifteenth printing, with a new Foreword, 2000 Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, and the Class of 1932 Lectureship. FIRST PRINCETON PAPERBACK Edition, 1971 Third printing, 1973 Tenth printing, 1990 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) {Permanence of Paper) www.pup.princeton.edu 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 Printed in the United States of America HELENAE UXORI Foreword NORTHROP FRYE IN RETROSPECT The publication of Northrop Frye's Notebooks troubled some of his old admirers, myself included. One unfortunate passage gave us Frye's affirmation that he alone, of all modern critics, possessed genius. I think of Kenneth Burke and of William Empson; were they less gifted than Frye? Or were George Wilson Knight or Ernst Robert Curtius less original and creative than the Canadian master? And yet I share Frye's sympathy for what our current "cultural" polemicists dismiss as the "romantic ideology of genius." In that supposed ideology, there is a transcendental realm, but we are alienated from it. -

Hereditary Genius-Its Laws and Consequences

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton Sir William Sydney, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick Soldier and knight and Duke of Northumberland; Earl of renown Marshal. “The minion of his time.” _________|_________ ___________|___ | | | | Lucy, marr. Sir Henry Sydney = Mary Sir Robt. Dudley, William Herbert Sir James three times Lord | the great Earl of 1st E. Pembroke Harrington Deputy of Ireland.| Leicester. Statesman and __________________________|____________ soldier. | | | | Sir Philip Sydney, Sir Robert, Mary = 2d Earl of Pembroke. Scholar, soldier, 1st Earl Leicester, Epitaph | courtier. Soldier & courtier. by Ben | | Johnson | | | Sir Robert, 2d Earl. 3d Earl Pembroke, “Learning, observation, Patron of letters. and veracity.” ____________|_____________________ | | | Philip Sydney, Algernon Sydney, Dorothy, 3d Earl, Patriot. Waller's one of Cromwell's Beheaded, 1683. “Saccharissa.” Council. First published in 1869. Second Edition, with an additional preface, 1892. Third corrected proof of the first electronic edition, 2000. Based on the text of the second edition. The page numbering and layout of the second edition have been preserved, as far as possible, to simplify cross-referencing. This is a corrected proof. Although it has been checked against the print edition, expect minor errors introduced by conversion and transcription. This document forms part of the archive of Galton material available at http://galton.org. Original electronic conversion by Michal Kulczycki, based on a facsimile prepared by Gavan Tredoux. This edition was edited, cross-checked and reformatted by Gavan Tredoux. HEREDITARY GENIUS AN INQUIRY INTO ITS LAWS AND CONSEQUENCES BY FRANCIS GALTON, F.R.S., ETC. London MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1892 The Right of Translation and Reproduction is Reserved ELECTRONIC CONTENTS PREFATORY CHAPTER TO THE EDITION OF 1892. -

Character Development in Terence's Eunuchus Samantha Davis

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 6-9-2016 Mixing the Roman miles: Character Development in Terence's Eunuchus Samantha Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds Recommended Citation Davis, Samantha. "Mixing the Roman miles: Character Development in Terence's Eunuchus." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Candidate Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: , Chairperson by THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico iii Acknowledgements I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my committee chair Professor Osman Umurhan, through whose genius, dedication, and endurance this thesis was made possible. Thank you, particularly, for your unceasing support, ever-inspiring words, and relentless ability to find humor in just about any situation. You have inspired me to be a better scholar, teacher, and colleague. I would also like to extend the sincerest thanks to my excellent committee members, the very chic Professor Monica S. Cyrino and the brilliant Professor Lorenzo F. Garcia Jr., whose editorial thoroughness, helpful suggestions, and constructive criticisms were absolutely invaluable. In addition, a thank you to Professor Luke Gorton, whose remarkable knowledge of classical linguistics has encouraged me to think about language and syntax in a much more meaningful way. -

American Paratexts: Experimentation and Anxiety in the Early United States Joshua Kopperman Ratner University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Fall 12-21-2011 American Paratexts: Experimentation and Anxiety in the Early United States Joshua Kopperman Ratner University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ratner, Joshua Kopperman, "American Paratexts: Experimentation and Anxiety in the Early United States" (2011). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 441. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/441 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/441 For more information, please contact [email protected]. American Paratexts: Experimentation and Anxiety in the Early United States Abstract “American Paratexts” argues that prefaces, dedications, footnotes, and postscripts were sites of aggressive courtship and manipulation of readers in early nineteenth-century American literature. In the paratexts of novels, poems, and periodicals, readers faced pedantic complaints about the literary marketplace, entreaties for purchases described as patriotic duty, and interpersonal spats couched in the language of selfless literary nationalism. Authors such as Washington Irving, John Neal, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and William Wells Brown turned paratexts into sites of instructional meta-commentary, using imperative and abusive reader-address to unsettle nda then reorient American readers, simultaneously insulting them for insufficiently adventuresome reading habits and declaring better reading and readers essential to America’s status in a transatlantic book sphere. That focus on addressivity transformed the tone and content of the early republic’s prose, bringing the viciousness of eighteenth-century coterie publishing into the emerging mass market world of nineteenth- century monthly and weekly periodicals. -

SHAKESPEARE PLAYING the PARATEXT in LOOKING for RICHARD University of Sussex, United Kingdom INFIDELIDADE

SEDUCTIVE INFIDELITY: SHAKESPEARE PLAYING THE PARATEXT IN LOOKING FOR RICHARD Martin John Fletcher ([email protected]) University of Sussex, United Kingdom Abstract: Although Shakespeare’s universal status as a literary genius seems assured, very few people today are able to grasp the complexities of his dramatic output. This paper exposes the challenges of attracting new audiences for Shakespeare and producing modern adaptations of his plays by focusing on the 1996 movie, Looking for Richard, directed by Al Pacino. By expertly blending documentary footage of rehearsals for a production of Richard III with scenes from the play and interviews with Shakespeare scholars, the movie reveals how actors, directors and academics themselves are often baffled by Shakespeare’s archaic language. The essay argues that Pacino ‘democratises’ the famous author by confronting Shakespeare’s daunting ‘aura’ in a disarming manner, and thereby winning over cinema audiences. Keywords: William Shakespeare. Looking for Richard. Cinematic adaptation. INFIDELIDADE SEDUTORA: SHAKESPEARE COMO PARATEXTO EM RICARDO III – UM ENSAIO Resumo: Embora a reputação universal de Shakespeare como um gênio literário parece assegurada, poucas pessoas hoje são capazes de compreender as complexidades de sua obra dramática. Este artigo expõe os desafios de atrair novos públicos para Shakespeare e produzir adaptações modernas de suas peças, concentrando-se no filme 1996, Ricardo III – Um ensaio, dirigido por Al Pacino. Através da hábil mistura de material documental de ensaios para a produção de Richard III com cenas da peça, e entrevistas com estudiosos de Shakespeare, o filme revela como atores, diretores e os próprios acadêmicos ficam muitas vezes perplexos com a linguagem arcaica de Shakespeare. -

The Meaning in Mimesis: Philosophy, Aesthetics, Acting Theory

The Meaning in Mimesis: Philosophy, Aesthetics, Acting Theory by Daniel Larlham Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Daniel Larlham All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Meaning in Mimesis: Philosophy, Aesthetics, Acting Theory Daniel Larlham Theatre as mimesis, the actor as mimic: can we still think in these terms, two and a half millennia after antiquity? The Meaning in Mimesis puts canonical texts of acting theory by Plato, Diderot, Stanislavsky, Brecht, and others back into conversation with their informing paradigms in philosophy and aesthetics, in order to trace the recurring impulse to theorize the actor’s art and the theatrical experience in terms of one-to-one correspondences. I show that, across the history of ideas that is acting theory, the familiar conception of mimesis as imagistic representation entangles over and over again with an “other mimesis”: mimesis as the embodied attunement with alterity, a human capacity that bridges the gap between self and other. When it comes to the philosophy of the theatre, it is virtually impossible to consider the one-to-one of representation or re- enactment without at the same time grappling with the one-to-one of identification or vicarious experience. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: The Meanings in Mimesis 1 1. Embodying Otherness: Mimesis, Mousike, and the Philosophy of Plato 18 2. The Felt Truth of Mimetic Experience: The Kinetics of Passion and the “Imitation of Nature” in the Eighteenth-Century Theatre 81 3. “I AM”; “I believe you”: Stanislavsky and the Oneness of Theatrical Subjectivity 138 4. -

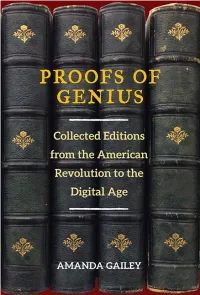

Proofs of Genius: Collected Editions from the American Revolution to the Digital Age, by Amanda Gailey Revised Pages

Revised Pages Proofs of Genius Revised Pages editorial theory and literary criticism George Bornstein, Series Editor Palimpsest: Editorial Theory in the Humanities, edited by George Bornstein and Ralph G. Williams Contemporary German Editorial Theory, edited by Hans Walter Gabler, George Bornstein, and Gillian Borland Pierce The Hall of Mirrors: Drafts & Fragments and the End of Ezra Pound’s Cantos, by Peter Stoicheff Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios: Scenes of Reading, Surfaces of Writing, by Marta L. Werner Scholarly Editing in the Computer Age: Theory and Practice, Third Edition, by Peter L. Shillingsburg The Literary Text in the Digital Age, edited by Richard J. Finneran The Margins of the Text, edited by D. C. Greetham A Poem Containing History: Textual Studies in The Cantos, edited by Lawrence S. Rainey Much Labouring: The Texts and Authors of Yeats’s First Modernist Books, by David Holdeman Resisting Texts: Authority and Submission in Constructions of Meaning, by Peter L. Shillingsburg The Iconic Page in Manuscript, Print, and Digital Culture, edited by George Bornstein and Theresa Tinkle Collaborative Meaning in Medieval Scribal Culture: The Otho Laȝamon, by Elizabeth J. Bryan Oscar Wilde’s Decorated Books, by Nicholas Frankel Managing Readers: Printed Marginalia in English Renaissance Books, by William W. E. Slights The Fluid Text: A Theory of Revision and Editing for Book and Screen, by John Bryant Textual Awareness: A Genetic Study of Late Manuscripts by Joyce, Proust, and Mann by Dirk Van Hulle The American Literature Scholar in the Digital Age, edited by Amy E. Earhart and Andrew Jewell Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850, edited by George Hutchinson and John K. -

Gerard Genette Paratexts Thresholds of Interpretation

Paratexts are those liminal devices and conventions, both within and outside the book, that form part of the complex mediation between book, author, publisher, and reader: titles, forewords, epigraphs, and pub- lishers' jacket copy are part of a book's private and public history. In Paratexts, an English translation of Seuils, Gerard Genette shows how the special pragmatic status of paratextual declarations requires a carefully calibrated analysis of their illocutionary force. With clarity, precision, and an extraordinary range of reference, Paratexts constitutes an encyclo- pedic survey of the customs and institutions of the Republic of Letters as they are revealed in the borderlands of the text. Genette presents a global view of these liminal mediations and the logic of their relation to the reading public by studying each element as a literary function. Richard Macksey's foreword describes how the poetics of paratexts interacts with more general questions of literature as a cultural institution, and situates Genette's work in contemporary literary theory. Literature, Culture, Theory 20 V" V V V V V V V V V V V V %mJ* V V V V V V V V V *J* 4t* •t* 4t* *t* *t* *t* •!* •t* *t* Paratexts: thresholds of interpretation Literature, Culture, Theory 20 «J» «J» «J» <J» «J» «J» *J» «J» VV V V V V V **• V 'I* V V V V V *•* V V V V * I* *** %m*p V V V *•* General editors RICHARD MACKSEY, The Johns Hopkins University and MICHAEL SPRINKER, State University of New York at Stony Brook The Cambridge Literature, Culture, Theory Series is dedicated to theoreti- cal studies in the human sciences that have literature and culture as their object of enquiry.