Modernity Student Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inity Church Utrecht and Anglican Church Zwolle

Holy Trinity Church Utrecht and Anglican Church Zwolle Illustration of Revelation 14:14-21 from the so-called Beatus Facundus, Spain, 11th century. September 2015 Newsletter Newsletter Editor Judy Miller [email protected] If you have contributions for the next Newsletter we need to receive them by the middle of the previous month. The contents of this newsletter are copyright. If you wish to reproduce any part of it elsewhere, please contact the editor. Holy Trinity Directory Van Hogendorpstraat 26, 3581 KE Utrecht www.holytrinityutrecht.nl The Bishop of Gibraltar: Robert Innes Tel: +44 20 7898 1160 Chaplain: David Phillips Tel: 06 124 104 31 [email protected] Administrative Assistant: Hanna Cremer Eindhoven Tel: 06 28 75 91 09 [email protected] Lay Pastoral Assistants: Peter Boswijk Tel: 06 211 152 79 Harry Barrowclough [email protected] Coordinator of Student Ministry: Eric Heemskerk Tel: 06 311 845 90 [email protected] Director of Music: Henk Korff: 06 53 13 00 86 [email protected] Wardens: Rosemarie Strengholt [email protected] Adrian Los: 06 11 88 50 75 [email protected] Treasurer: Sandra Sue Tel: 035 694 59 53 [email protected] Secretary: Simon Urquart [email protected] If you would like to make a contribution to support the work of our churches: Holy Trinity Utrecht General Giving: NL84INGB0000132950 – tnv Holy Trinity Church Utrecht Charitable Giving: NL92TRIO019772361 – tnv Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Utrecht Anglican Church Zwolle General Giving: NL02 INGB 0007 2290 06 - tnv English Church Zwolle Cover Image: Facundus made a copy in 1047of an earlier manuscript on Revelation. -

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

Revue Internationale De La Croix-Rouge Et Bulletin Des Societes De La Croix-Rouge

REVUE INTERNATIONALE DE LA CROIX-ROUGE ET BULLETIN DES SOCIETES DE LA CROIX-ROUGE SUPPLEMENT First Year, I948 GENEVE 1948 SUPPLEMENT VOL. I REVUE INTERNATIONALE DE LA CROIX-ROUGE ET BULLETIN DES SOCIETES DE LA CROIX-ROUGE SUPPLEMENT March,1948 NO·3 CONTENTS Page Mission of the International Committee in Palestine . .. 42 Mission of the International Committee to the United States and to Canada . 43 The Far Eastern Conflict (Part I) 45 Published by Comite international de la Croix-Rouge, Geueve Editor: Louis Demolis MISSION OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE IN PALESTINE In pursuance of a request made by the Government of the mandatory Power in Palestine, the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva, who had previously been authorized to visit the camps of persons detained in consequence of recent events, have despatched a special mission to Palestine. This . mission has been instructed to study, in co-operation with all parties, the problems arising from the humanitarian work which appears to be indispensable in view of the present situation. The Committee's delegates have met on all hands with a most frie~dly reception. During the last few weeks, they have had talks with the Government Authorities and the Arab and Jewish representatives; they have offered to all concerned the customary services of the Committee as a neutral intermediary, having in mind especially the protection and care of wounded, sick and prisoners. During their tour of the country the Committee's delegates visited a large number of hospitals and refugee camps, and collected information on the present needs in hospital staff, doctors and nurses, as well as in ambulances and medical supplies. -

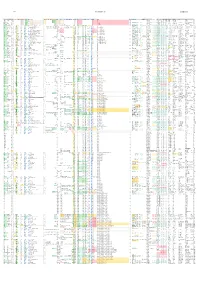

Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72

8/27/2021 Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72 https://haplogroup.info/ Object‐ID Colloquial‐Skeletal LatitudLongit Sex mtDNA‐comtFARmtDNA‐haplogroup mtDNA‐Haplotree mt‐FT mtree mt‐YFFTDNA‐mt‐Haplotree mt‐Simmt‐S HVS‐I HVS‐II HVS‐NO mt‐SNPs Responsible‐ Y‐DNA Y‐New SNP‐positive SNP‐negative SNP‐dubious NRY Y‐FARY‐Simple YTree Y‐Haplotree‐VY‐Haplotree‐PY‐FTD YFull Y‐YFu ISOGG2019 FTDNA‐Y‐Haplotree Y‐SymY‐Symbol2Responsible‐SNPSNPs AutosomaDamage‐RAssessmenKinship‐Notes Source Method‐Date Date Mean CalBC_top CalBC_bot Age Simplified_Culture Culture_Grouping Label Location SiteID Country Denisova4 FR695060.1 51.4 84.7 M DN1a1 DN1a1 https:/ROOT>HD>DN1>D1a>D1a1 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 708,133.1 (549,422.5‐930,979.7) A0000 A0000 A0000 A0000 A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 84.1–55.2 ka [Douka ‐67700 ‐82150 ‐53250 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Denisova8 KT780370.1 51.4 84.7 M DN2 DN2 https:/ROOT>HD>DN2 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 706,874.9 (607,187.2‐833,211.4) A0000 A0000‐T A0000‐T A0000‐T A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 136.4–105.6 ka ‐119050 ‐134450 ‐103650 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Spy_final Spy 94a 50.5 4.67 .. ND1b1a1b2* ND1b1a1b2* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a>ND1b1a1>ND1b1a1b>ND1b1a1b2 ND L C6563T * A11YFull TMRCA ca. 369,637.7 (326,137.1‐419,311.0) A000 A000a A000a A000‐T>A000>A000a A0 A000 PetrbioRxiv2020 553719 0.66381 .. PASS (literan/a HajdinjakNature2018 from MeyDirect: 95.4%; IntCal20, OxC39431‐38495 calBCE ‐38972 ‐39431 ‐38495 Neanderthal Late Middle Palaeolithic Spy_Neanderthal.SG Grotte de Spy, Jemeppe‐sur‐Sambre, Namur Belgium El Sidron 1253 FM865409.1 43.4 ‐5.33 ND1b1a* ND1b1a* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a ND L YFull TMRCA ca. -

Dental Trauma and Antemortem Tooth Loss in Prehistoric Canary Islanders: Prevalence and Contributing Factors

International Journal of Osteoarchaeology Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. (in press) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/oa.864 Dental Trauma and Antemortem Tooth Loss in Prehistoric Canary Islanders: Prevalence and Contributing Factors J. R. LUKACS* Department of Anthropology University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-1218, USA ABSTRACT Differential diagnosis of the aetiology of antemortem tooth loss (AMTL) may yield important insights regarding patterns of behaviour in prehistoric peoples. Variation in the consistency of food due to its toughness and to food preparation methods is a primary factor in AMTL, with dental wear or caries a significant precipitating factor. Nutritional deficiency diseases, dental ablation for aesthetic or ritual reasons, and traumatic injury may also contribute to the frequency of AMTL. Systematic observations of dental pathology were conducted on crania and mandibles at the Museo Arqueologico de Tenerife. Observations of AMTL revealed elevated frequencies and remarkable aspects of tooth crown evulsion. This report documents a 9.0% overall rate of AMTL among the ancient inhabitants of the island of Tenerife in the Canary Archipelago. Sex-specific tooth count rates of AMTL are 9.8% for males and 8.1% for females, and maxillary AMTL rates (10.2%) are higher than mandibular tooth loss rates (7.8%) Dental trauma makes a small but noticeable contribution to tooth loss among the Guanches, especially among males. In several cases of tooth crown evulsion, the dental root was retained in the alveolus, without periapical infection, and alveolar bone was in the initial stages of sequestering the dental root. In Tenerife, antemortem loss of maxillary anterior teeth is consistent with two potential causal factors: (a) accidental falls while traversing volcanic terrain; and (b) interpersonal combat, including traditional wrestling, stick-fighting and ritual combat. -

Bull23 Final.Qxd

ISSN 0306 1698 comhairle uamh-eolasach na monadh liath the grampian speleological group BULLETIN Fourth Series vol.2 no.3 March 2005 Price £2 2 GSG Bulletin Fourth Series Vol.2 No.3 CONTENTS Page Number Editorial 3 Area Meet Reports 4 Meet Report: Fairy Cave, Luing 7 Additions to the Library 8 Getting Damp in Draenen 11 Big Hopes for Little Igloos 12 Scottish Speleophilately 13 Uamh an Righ (Cave of the Kings), Kishorn 16 Book Review: ‘It’s Only a Game’ 18 Craiglea Slate Quarry, Perthshire 19 Scottish Cave Ephemera 26 A Trip to Anguilla 27 Meet Note: St George’s Cave, Assynt 31 Grutas de Calcehtok, Yucatan 32 Meet Note: Limestone Mine, Bridge of Weir 36 Skye High (and Low) 37 Vancouver Island Adventures 2004 40 Cover: Wine and Cheese at the bottom of Sunset Hole, August 1983. (L.to R. [Charles Frankland] Nigel Robertson, Ivan Young, Jackie Yuill. Photo. Ivan Young. Obtainable from: The Grampian Speleological Group 8 Scone Gardens EDINBURGH EH8 7DQ (0131 661 1123) Web Site: http://www.sat.dundee.ac.uk/~arb/gsg/ E-mail (Editorial) [email protected] 3 The Grampian Speleological Group EDITORIAL: Recently, I was lunching with a few like-minded friends when I offered for sale a book which, when pub- lished, had been a seminal work on ancient Egyptian religion. A fellow diner, a distinguished Egyptologist, dismissed this with the comment: “But it’s fifty years old”, the clear inference being that it no longer served any useful purpose. I suppose this verdict would be applicable to a huge volume of scientific or investiga- tory texts. -

No. 3 September 2005 Published Quarterly by the Committee On

Volume 24 - No. 3 September 2005 Published quarterly by the Committee on Relations with Churches Abroad of The Reformed Churches in the Netherlands Published quarterly by the Committee Contents on Relations with churches Abroad of The Reformed Churches in Editorial The Netherlands By R. ter Beek, p. 65 Volume 24 - No. 3 September 2005 Joy and more joy! By H.G.L. Peels, p. 66 Editors: Rev. J.M. Batteau New Committee for Relations with Churches abroad Gkv (BBK) Rev. R. ter Beek p. 67 Ms. C. Scheepstra Mr. P.G.B. de Vries The foundation for Helping Neighbours abroad By P. Hooghuis, p.68 Mrs. S. Wierenga-Tucker Reformed theology: between ideal and reality (II) By G. Kwakkel, p.70 Address for Editorial and Administrative (subscriptions, change of address) A marginalised phenomenon Matters: By R. ter Beek, p. 73 Lux Mundi Postbus 499 The proclamation of the Gospel to the Jews By H.J. Siegers, p. 77 8000 AL Zwolle The Netherlands America: with or against the world? Telephone: +31(0)38 427 04 70 By A. Kamsteeg, p. 79 E-mail: [email protected] Contacts in North America Bank account: no. 1084.32.556 By R.C. Janssen, p. 82 Subscription Rate in The Netherlands per annum: Hans Rookmaaker and the struggle for a Christian view of art and culture € 7,50. By W.L. Meijer, p. 84 ICRC Pretoria 2005 p. 86 News Update News from Kampen (GKv), p. 87 GKv offers sister-church relationship to GKSA, p. 88 by R. ter Beek Editorial In the coming days, the General Synod of the Reformed on Friday and Saturday. -

ARQUEOLOGIA 1 Bloantropologla Volumen 14 MUSEO ARQUEOLOGICO DE TENERIFE

ERES ARQUEOLOGIA 1 BlOANTROPOLOGlA Volumen 14 MUSEO ARQUEOLOGICO DE TENERIFE INSTITUTO CANARIO DE BlOANTROPOLOGlA Sumario Otros conceptos. otras miradas nuestra arqueologla. A sobre la religión de los guanches: propósito de los Cinithi o Rafael González Antón et al1 El Zanatas: Rafael González Antón lugar arqueológico de Butihondo et al/ La Antropologia Física y (Fuerteventura): M' del Carmen su aplicación a -la justicia en del Arco Aguilar et al1 España: una perspectiva Prospección arqueológica del histórica: Conrado Rodriguez litoral del sur de la Isla deTenerife: Martin et al1 Problemas Granadilla, San Miguel de Abona conceptuales de las y Arona:Alfredo Mederos Martín entesopatias en Paleopatologla: et al1 Sobre el V Congreso Dornenec Campillo et al/ The Panafricano de Prehistoria (Islas leprosarium of Spinalonga Canarias, 1963): Enrique Gozalbes (1 903- 1957) in eastern Crete Craviotol Relectura sobre (Greece): Chryssi Bourbou ORGANISMO AUlüNOMO DE MUSEOS Y CENTROS . COMITÉEDITORIAL - , . , . .. Dirección . : RAFAEL GONZALEZ ANTÓN arqueología)^' CONRADO RODRÍGUEZ MARTÍN '(Bioantropología) ' 7 , . .. ; . Secretaría ,,., ..;',!'.:.. ' CANDELARIA ROSARIO ADRIÁN: .- , ?, . MERCEDES DELARCO AGUILAR . -."' ' -, ,. , ,. %, %, Consejo Editorial . ., ENRIQUE GOZALBES CRAVIOTO JOSÉ CARLOS CABRERA PEREZ (Univ. Castilla-La Mancha) . (Patrimonio Histórico. Cabildo de Tenerife) . JOAN RAMÓN TORRES' . JOSE J. JIMÉNEZ GONZÁL.EZ . ' (Unidad de Patrimonio.' (Museo Arqueológicode Tenerife. Diputación de Ibiza) .' . O.A.M.C.) ' Consejo Asesor ARTHUR C. AUFDERHEIDE' FERNANDO ESTÉVEZ. GONZÁLEZ: (Univ. de Minnesota) ,. .! ' . '. (Univ. de La Lagunaj ' ' . , : . - . ., . , RODRIGO DE BALBÍN BEH~ANN : PRIMITIVA BUENO RAM~REZ : ' (Univ. de Aicalá de ~enaks) - . .. (Univ. de Alcalá de'Henares) ... , . , .. ANTONIO;SANTANA SAF~TANA ' ..PABLO ATOCHE PEÑA (Univ. de Las Pa1mas)j. ' (Univ. de Las Palmas) . , ; ... FRANCISCO-r~~~~í~-~~~~.v~~CASAÑAS . .. (M&eo"de kiencias Nakra'íe~.O.A.M.C.) , . -

Reproachless Heroes of World War 11: a Cinematic Approach Through Two American Movies

~ S T 0 + • .; ~ .,.. Volume m Number 1-2 1993 o.l .. .......... 9' REPROACHLESS HEROES OF WORLD WAR 11: A CINEMATIC APPROACH THROUGH TWO AMERICAN MOVIES CHRISTINE S. DILIGENTI-GA VRILINE Lycee Ozar Hatorah, Toulouse As a manly universe, war is above all a soldierly one, the one of fighting armies. Cinema does not derogate to the tradition of representing troops, resting or acting, clean and fresh on the eve of the battle, mud bespattered and devastated afterwards. Looks do not interest us much, even though the circular travellings in Tora! Tora! 'J'ora! for instance, let us admire or appreciate the fine presence of the uniforms: the masterful first images of the film when the entire Japanese Navy, in #1 Ceremonial, greets her new chief-commander, Admiral Yamamoto. The army at wartime still is a particular sphere in the bosom of the State, if she doesn't purely serve as a substitute for it The army is submitted to law and statutes (discipline), obeys to a hierarchy (ranks) that we can, why not. compare to the common social ladder, even if it is not inevitably the social origin that makes the gold braid. The major interest of the classical war cinema is to show soldiers and the army at their best They are the symbol of the unity of the nation against the dangerous enemy that they must fight It is their mission to defeat him. There are numerous movies reflecting this point of view. The American film industry has long been lavish on this subject with movies where John Wayne assumes the part of the hero. -

Clayton Eshleman/Notes on Charles Olson and the Archaic1

CLAYTON ESHLEMAN/NOTES ON CHARLES OLSON AND THE ARCHAIC1 for Ralph Maud 1] On May 20, 1949, Francis Boldereff sent S.N. Kramer’s article, “The Epic of Gilgame and It Sumerian Sources” to her recently-discovered poet-hero and correspondent, Charles Olson. At two points in the article, Kramer presents scholarly verse translation of two sections concerning Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Underworld. In the first section, Gilgamesh’s pukku (“drum”) and mikkû (‘drumstick”) have fallen into the Underworld. Unable to reach them from this world, he sits at the gate of the Underworld and laments: O my pukku, O my mikkû, My pukku whose lustiness was irresistible, My mikkû whose pulsations could not be drowned out, In those days when verily my pukku was with me in the house of the carpenter, (When) verily the wife of the carpenter was with me like the mother who gave birth to me, (When) verily the daughter of the carpenter was with me like my younger sister, My pukku, who will bring it up from the nether world, My mikkû, who will bring it up from the ‘face’ of the nether world? A week later, Olson sent his adaptation of these lines to Boldereff: LA CHUTE O my drum, hollowed out thru the thin slit, carved from the cedar wood, the base I took when the tree was felled o my lute 1 This lecture, commissioned by Robert Creeley, was given in the Special Collections Library at the SUNY-Buffalo, on October 22/23, 2004. It was published in Minutes of the Charles Olson Society #52 wrought from the tree’s crown my drum whose lustiness was not to be resisted my lute from whose pulsations not one could turn away they are where the dead are my drum fell where the dead are, who will bring it up, my lute who will bring it up where it fell in the face of them where they are, where my lute and drum have fallen? Olson has added information from Kramer’s explanation of prior material in the poem. -

Homo Erectus, Became Extinct About 1.7 Million Years Ago

Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.BearandCompanyBooks.com Bear & Company is a division of Inner Traditions International Copyright © 2013 by Frank Joseph All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Joseph, Frank. Before Atlantis : 20 million years of human and pre-human cultures / Frank Joseph. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. Summary: “A comprehensive exploration of Earth’s ancient past, the evolution of humanity, the rise of civilization, and the effects of global catastrophe”—Provided by publisher. print ISBN: 978-1-59143-157-2 ebook ISBN: 978-1-59143-826-7 1. Prehistoric peoples. 2. Civilization, Ancient. 3. Atlantis (Legendary place) I. Title. GN740.J68 2013 930—dc23 2012037131 Chapter 8 is a revised, expanded version of the original article that appeared in The Barnes Review (Washington, D.C., Volume XVII, Number 4, July/August 2011), and chapter 9 is a revised and expanded version of the original article that appeared in The Barnes Review (Washington, D.C., Volume XVII, Number 5, September/October 2011). Both are republished here with permission. To send correspondence to the author of this book, mail a first-class letter to the author c/o Inner Traditions • Bear & Company, One Park Street, Rochester, VT 05767, and we will forward the communication. BEFORE ATLANTIS “Making use of extensive evidence from biology, genetics, geology, archaeology, art history, cultural anthropology, and archaeoastronomy, Frank Joseph offers readers many intriguing alternative ideas about the origin of the human species, the origin of civilization, and the peopling of the Americas.” MICHAEL A. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 436 445 SO 030 794 TITLE China: Tradition and Transformation, Curriculum Projects. Fulbright Hays Summer Seminars Abroad 1998 (China). INSTITUTION National Committee on United States-China Relations, New York, NY. SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 393p.; Some pages will not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Asian History; *Chinese Culture; Communism; *Cultural Context; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Learning Activities; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Student Educational Objectives; *Study Abroad IDENTIFIERS *China; Chinese Art; Chinese Civilization; Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; Japan ABSTRACT The curriculum projects in this collection focus on diverse aspects of China, the most populous nation on the planet. The 16 projects in the collection are:(1) "Proposed Secondary Education Asian Social Studies Course with an Emphasis on China" (Jose Manuel Alvarino); (2) "Education in China: Tradition and Transition" (Sue Babcock); (3)"Chinese Art & Architecture" (Sharon Beachum); (4) "In Pursuit of the Color Green: Chinese Women Artists in Transition" (Jeanne Brubaker); (5)"A Host of Ghosts: Dealing with the Dead in Chinese Culture" (Clifton D. Bryant); (6) "Comparative Economic Systems: China and Japan" (Arifeen M. Daneshyar); (7) "Chinese, Japanese, and American Perspectives as Reflected in Standard High School Texts" (Paul Dickler); (8) "Gender Issues in Transitional China" (Jana Eaton); (9) "A Walking Tour of Stone Village: Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics" (Ted Erskin); (10) "The Changing Role of Women in Chinese Society" (John Hackenburg); (11) "Healing Practices: Writing Chinese Culture(s) on the Body: Confirming Identity, Creating Identity" (Sondra Leftoff); (12) "Unit on Modern China" (Thomas J.