Sons of Heracles: Antony and Alexander in the Late Republic Kyle Erickson, University of Wales Trinity Saint David

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heracles's Weariness and Apotheosis in Classical Greek Art

Dourado Lopes, Antonio Orlando Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art Synthesis 2018, vol. 25, nro. 2, e042 Dourado Lopes, A. (2018). Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art. Synthesis, 25 (2), e042. En Memoria Académica. Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.10707/pr.10707.pdf Información adicional en www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ ARTÍCULO / ARTICLE Synthesis, vol. 25, nº 2, e042, diciembre 2018. ISSN 1851-779X Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Centro de Estudios Helénicos Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art Agotamiento físico y apoteosis de Heracles en el arte clásico griego Antonio Orlando Dourado Lopes Universidad Federal de Minas Gerais, Brasil [email protected] Resumen: Este estudio propone una interpretación general de las imágenes realizadas en Grecia, a partir del siglo V a. C. en monedas, joyas, pinturas de vasijas y esculturas, que muestran el agotamiento físico de Heracles y su apoteosis divina. Luego de una extendida consideración de los principales trabajos académicos que abordaron el tema desde finales del siglo XIX, procuro mostrar que la representación iconográfica del agotamiento de Heracles y de su apoteosis da testimonio de la influencia de nuevas concepciones religiosas y filosóficas en su mito, fundamentalmente del pitagorismo, del orfismo y de los cultos mistéricos, así como del fuerte intelectualismo de la Atenas del siglo V a. C. -

The Argonautica, Book 1;

'^THE ARGONAUTICA OF GAIUS VALERIUS FLACCUS (SETINUS BALBUS BOOK I TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY H. G. BLOMFIELD, M.A., I.C.S. LATE SCHOLAR OF EXETER COLLEGE, OXFORD OXFORD B. H. BLACKWELL, BROAD STREET 1916 NEW YORK LONGMANS GREEN & CO. FOURTH AVENUE AND 30TH STREET TO MY WIFE h2 ; ; ; — CANDIDO LECTORI Reader, I'll spin you, if you please, A tough yarn of the good ship Argo, And how she carried o'er the seas Her somewhat miscellaneous cargo; And how one Jason did with ease (Spite of the Colchian King's embargo) Contrive to bone the fleecy prize That by the dragon fierce was guarded, Closing its soporific eyes By spells with honey interlarded How, spite of favouring winds and skies, His homeward voyage was retarded And how the Princess, by whose aid Her father's purpose had been thwarted, With the Greek stranger in the glade Of Ares secretly consorted, And how his converse with the maid Is generally thus reported : ' Medea, the premature decease Of my respected parent causes A vacancy in Northern Greece, And no one's claim 's as good as yours is To fill the blank : come, take the lease. Conditioned by the following clauses : You'll have to do a midnight bunk With me aboard the S.S. Argo But there 's no earthly need to funk, Or think the crew cannot so far go : They're not invariably drunk, And you can act as supercargo. — CANDIDO LECTORI • Nor should you very greatly care If sometimes you're a little sea-sick; There's no escape from mal-de-mer, Why, storms have actually made me sick : Take a Pope-Roach, and don't despair ; The best thing simply is to be sick.' H. -

Mark Antony's Oration from Julius Caesar

NAME: ______________________________________ Mark Antony’s Oration from Julius Caesar In William Shakespeare’s play, Julius Caesar, Caesar has been assassinated in front of the Senate by a group of Roman offi cials, including his friend, Brutus. After the murder, Brutus speaks to the gathered crowd. He convinces them that the conspirators killed Caesar to save Rome. Mark Antony is another Roman offi cial and friend to Caesar who did not participate in the murder. Antony promises Brutus that he will not blame the conspirators if he is allowed to make a speech also. Act III Scene II Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; When that the poor have cried, Caesar hath wept: I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. Ambition should be made of sterner stuff: The evil that men do lives after them; Yet Brutus says he was ambitious; The good is oft interred with their bones: And Brutus is an honourable man. So let it be with Caesar. The noble Brutus You all did see that on the Lupercal Hath told you Caesar was ambitious: I thrice presented him a kingly crown, If it were so, it was a grievous fault; Which he did thrice refuse: was this ambition? And grievously hath Caesar answer’d it. Yet Brutus says he was ambitious; Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest,— And, sure, he is an honourable man. For Brutus is an honourable man; I speak not to disprove what Brutus spoke, So are they all, all honorable men,— But here I am to speak what I do know. -

The Heracles : Myth Becoming

Natibnal Library Bibhotheque naticmale I* of Canada du Canada Canadian Theses Service Services des theses canadiennes Ottawa, Canada K1 A ON4 CANADIAN THESES THESES CANADIENNES NOTICE The quality of this microfiche is heavily dependent upon the La qualite de cette microfiche depend grandement de la qualite quality of the original thesis submitted fcr microfilming. Every de la these soumise au microfilmage. Nous avons tout fail pour effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduc- assurer uoe qualit6 superieure de reproduction. tion possible. D If pages are missing, contact the university which granted the S'il 'manque des pages, veuillez communiquer avec I'univer- degree. Some pages may have indistinct print especially if the original certatnes pages peut laisser A pages were typed with a poor typewriter ribbon or if the univer-- ont 6t6 dactylographi6es sity sent us an inferior photocopy. a I'aide d'un ruban us6 ou si Imuniversit6nous a fa;t parvenir une photocopie de qualit6 inf6rieure. Previously copyrighted materials (journal articles, published cuments qui font d6jA I'objet d'un droit d'auteur (articles tests, etc.) are not filmed. ue, examens publi&, etc.) ne sont pas microfilmes. Reproduction in full or in part of this film is governed by the La reproduction, mGme partielle, de ce microfilm est soumke Canadian Copyright Act, R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30. A la Loi canadienne sur le droit d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C-30. THIS DI~ERTATION LA THESE A ETE HAS BEEN iICROFILMED M~CROFILMEETELLE QUE EXACTLY AS RECEIVED NOUS L'AVONS REGUE THE HERACLES: MYTH BECOMING MAN. -

Augustus Go to and Log in Using Your School’S Log in Details

Timelines – Augustus Go to www.worldbookonline.com and log in using your school’s log in details: Log-in ID: Password: Click on Advanced Type in Augustus in Search box Click the article titled Augustus Read the article and answer the questions below. 1. What date was Octavian (Augustus) born? ___________________________________________________________________________ 2. In which year did Octavian take the name Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus? ___________________________________________________________________________ 3. Octavian defeated Mark Antony, who had taken control of Rome following Caesar’s death, in which year? ___________________________________________________________________________ 4. Octavian and Mark Antony formed a political alliance, known as the Second Triumvirate, with Markus Aemilius Lepidus (chief priest of Rome). In which year were Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, Caesar’s chief assassins, defeated at Philippi in Macedonia? ___________________________________________________________________________ 5. What year was another threat, Sextus Pompey (son of Pompey the Great), defeated by Antony and Octavian? ___________________________________________________________________________ 6. In what year did the Triumvirate disintegrate? ___________________________________________________________________________ 7. In what year did Mark Antony and Cleopatra (Queen of Egypt) become lovers? ___________________________________________________________________________ 8. In what year did Octavian go to war against -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

Stuart Lochhead Sculpture

Stuart Lochhead Sculpture Stuart Lochhead Limited www.stuartlochhead.art 020 3950 2377 [email protected] Auguste Jean-Marie Carbonneaux Paris, 1769-1843 Hercules, after the Antique bronze 73 cm high Signed and dated Carbonneaux 1819 on the right side of the base Related literature ■ E. Lebon, « Répertoire », in Le fondeur et le sculpteur, Paris, Ophrys (« Les Essais de l'INHA »), 2012 [also available online] Stuart Lochhead Limited www.stuartlochhead.art 020 3950 2377 [email protected] Auguste Jean-Marie Carbonneaux is one of the pioneers of the technique of sand-casting for monumental sculpture. Not a lot is known about his life but a recent publication by E. Lebon (see lit.) has shed some light on his career. Born into a family of metal workers, Carbonneaux is known to be active as a founder from 1814. In 1819 at the request of the celebrated sculptor François-Joseph Bosio (1768-1845) he received the prestigious commission to execute the equestrian statue of Louis XIV for the Place des Victoires, Paris, which was unveiled in 1822. Carbonneaux cast the statue and the two men worked together at least one more time since he also executed in bronze Bosio’s large group of Hercules fighting Achelous transformed into a snake, a statue commissioned by the French royal household in 1822, exhibited at the Salon of 1824 and now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris. Clearly recognised as being an excellent founder, Carbonneaux was also selected by the Polish-French count Leon Potocki in 1821 to cast the equestrian portrait of the polish statesman and general Josef Poniatowski by Berthel Thorvaldsen1. -

Spectacle Theater

SUN MON TUES Wed thurs fri SAT 1 2 3 4 5 SPECTACLE 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 PROTECTORS OF THE Queen of burlesque THE PINK EGG EAT MY DUST LADY OF BURLESQUE UNIVERSE Director Q&A! 7:30 10:00 10:00 10:00 FLASH FUTURE KUNG FU SPACE THUNDER KIDS HARD BASTARD 10:00 LITTLE MAD GUY 10:00 LADY OF BURLESQUE DArnA VS. THE PLANET WOMEN Midnight HERCULES UNCHAINED Midnight THE HORROR OF SPIDER ISLAND 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 blood brunch the pink egg Solar adventure dog day pizza, birra, Faso flash future kung fu lady of burlesque 5:00 7:30 keep cool 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 darna vs. the planet lost & forgotten cinema little mad guy space transformer eat my dust protectors of the space thunder kids women 7:30 universe Contemporary underground • special events Queen of burlesque 10:00 Midnight hard bastard the horror of spider island Midnight I.K.U. 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 & 10:00 5:00 fist church hard bastard pizza, birra, Faso Queen of burlesque dog day silent lovers yeast ONE NIGHT ONLY! 5:00 7:30 the pink egg 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 8Ball tv space transformer keep cool darna vs. the planet solar adventure Midnight ONE NIGHT ONLY! 7:30 women the horror of spider eat my dust island 10:00 little mad guy Midnight hercules unchained 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 blood brunch solar adventure MATCH CUTS PRESENTS Queen of burlesque eat my dust keep cool space transformer ONE NIGHT ONLY! 5:00 7:30 flash future kung fu 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 space thunder kids dog day I.K.U hard bastard YEAST the pink egg 7:30 10:00 space thunder kids I.K.U. -

Folktale Types and Motifs in Greek Heroic Myth Review P.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic Quest

Mon Feb 13: Heracles/Hercules and the Greek world Ch. 15, pp. 361-397 Folktale types and motifs in Greek heroic myth review p.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic quest NAME: Hera-kleos = (Gk) glory of Hera (his persecutor) >p.395 Roman name: Hercules divine heritage and birth: Alcmena +Zeus -> Heracles pp.362-5 + Amphitryo -> Iphicles Zeus impersonates Amphityron: "disguised as her husband he enjoyed the bed of Alcmena" “Alcmena, having submitted to a god and the best of mankind, in Thebes of the seven gates gave birth to a pair of twin brothers – brothers, but by no means alike in thought or in vigor of spirit. The one was by far the weaker, the other a much better man, terrible, mighty in battle, Heracles, the hero unconquered. Him she bore in submission to Cronus’ cloud-ruling son, the other, by name Iphicles, to Amphitryon, powerful lancer. Of different sires she conceived them, the one of a human father, the other of Zeus, son of Cronus, the ruler of all the gods” pseudo-Hesiod, Shield of Heracles Hera tries to block birth of twin sons (one per father) Eurystheus born on same day (Hera heard Zeus swear that a great ruler would be born that day, so she speeded up Eurystheus' birth) (Zeus threw her out of heaven when he realized what she had done) marvellous infancy: vs. Hera’s serpents Hera, Heracles and the origin of the MIlky Way Alienation: Madness of Heracles & Atonement pp.367,370 • murders wife Megara and children (agency of Hera) Euripides, Heracles verdict of Delphic oracle: must serve his cousin Eurystheus, king of Mycenae -> must perform 12 Labors (‘contests’) for Eurystheus -> immortality as reward The Twelve Labors pp.370ff. -

THE HERO and HIS MOTHERS in SENECA's Hercules Furens

SYMBOLAE PHILOLOGORUM POSNANIENSIUM GRAECAE ET LATINAE XXIII/1 • 2013 pp. 103–128. ISBN 978-83-7654-209-6. ISSN 0302-7384 Mateusz Stróżyński Instytut Filologii Klasycznej Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza ul. Fredry 10, 61-701 Poznań Polska – Poland The Hero and His Mothers in Seneca’S Hercules FUreNs abstraCt. Stróżyński Mateusz, The hero and his mothers in Seneca’s Hercules Furens. The article deals with an image of the heroic self in Seneca’s Hercules as well as with maternal images (Alcmena, Juno and Megara), using psychoanalytic methodology involving identification of complementary self-object relationships. Hercules’ self seems to be construed mainly in an omnipotent, narcissistic fashion, whereas the three images of mothers reflect show the interaction between love and aggression in the play. Keywords: Seneca, Hercules, mother, psychoanalysis. Introduction Recently, Thalia Papadopoulou have observed that the critics writing about Seneca’s Hercules Furens are divided into two groups and that the division is quite similar to what can be seen in the scholarly reactions to Euripides’ Her- akles.1 However, the reader of Hercules Furens probably will not find much 1 See: T. Papadopoulou, Herakles and Hercules: The Hero’s ambivalence in euripides and seneca, “Mnemosyne” 57:3, 2004, pp. 257–283. The author reviews shortly the literature about the play and in the first group of critics, of those who are convinced that Hercules is “mad” from the beginning, but his madness gradually develops, she enumerates Galinsky (G.K. Galinsky, The Herakles Theme: The adaptations of the Hero in literature from Homer to the Twentieth Century, Oxford 1972), Zintzen (C. -

The Hercules Story Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HERCULES STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin W. Bowman | 128 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752450810 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom The Hercules Story PDF Book More From the Los Angeles Times. The god Apollo. Then she tried to kill the baby by sending snakes into his crib. Hercules was incredibly strong, even as a baby! When the tasks were completed, Apollo said, Hercules would become immortal. Deianira had a magic balm which a centaur had given to her. July 23, Hercules was able to drive the fearful boar into snow where he captured the boar in a net and brought the boar to Eurystheus. Greek Nyx: The Goddess of the Night. Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the wild boar from the mountain of Erymanthos. Like many Greek gods, Poseidon was worshiped under many names that give insight into his importance Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. Athena observed Heracles shrewdness and bravery and thus became an ally for life. The name Herakles means "glorious gift of Hera" in Greek, and that got Hera angrier still. Feb 14, Alexandra Dantzer. History at Home. Hercules was born a demi-god. On Wednesday afternoon, Sorbo retweeted a photo of some of the people who swarmed the U. Hercules could barely hear her, her whisper was that soft, yet somehow, and just as the Oracle had predicted to herself, Hera's spies discovered what the Oracle had told him. As he grew and his strength increased, Hera was evermore furious. -

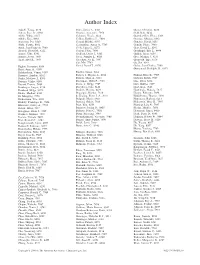

Author Index

Author Index Adachi, Yasuo, 8126 Clark, James A., 8361 Glover, Christian, 8410 Aitken, Jesse D., 8280 Cloutier, Alexandre, 7958 Gold, Ralf, 8434 Akiba, Yukio, 8327 Coleman, Nicole, 8222 Gonzalez-Rey, Elena, 8369 Alitalo, Kari, 8048 Collins, Kathleen L., 7804 Gorospe, Myriam, 8342 Anderson, Per, 8369 Conrad, Heinke, 8135 Goucher, David, 8231 Araki, Yasuto, 8102 Constantino, Agnes A., 7783 Gourdy, Pierre, 7980 Arnal, Jean-Franc¸ois, 7980 Cook, James L., 8272 Gray, David L., 8241 Aronoff, David M., 8222 Coulon, Flora, 7898 Greidinger, Eric L., 8444 Atasoy, Ulus, 8342 Crofford, Leslie J., 8361 Griffith, Jason, 8250 August, Avery, 7869 Cross, Jennifer L., 8020 Gros, Marilyn J., 8153 Azad, Abul K., 7847 Crowther, Joy E., 7847 Grunwald, Ingo, 8176 Cui, Min, 7783 Gu, Jun, 8011 Bagley, Jessamyn, 8168 Curiel, David T., 8126 Gue´ry, Jean-Charles, 7980 Bajer, Anna A., 8109 Guinamard, Rodolphe R., 8153 Balakrishnan, Vamsi, 8159 Daefler, Simon, 8262 Banerjee, Anirban, 8192 Damen, J. Mirjam A., 8184 Haddad, Elias K., 7969 Banks, Matthew I., 8393 Daniels, Mark A., 8211 Halwani, Rabih, 7969 Baranyi, Ulrike, 8168 Davenport, Miles P., 7938 Hao, Yibai, 8222 Bayard, Francis, 7980 Davis, T. Gregg, 7989 Hara, Hideki, 7859 Bernhagen, Jurgen, 8250 Davydova, Julia, 8126 Hase, Koji, 7840 Bernhard, Helga, 8135 Deckert, Martina, 8421 Hashimoto, Makoto, 7827 Bhatia, Madhav, 8333 Degauque, Nicolas, 7818 Haspot, Fabienne, 7898 Bi, Mingying, 7793 de Koning, Pieter J. A., 8184 Haudebourg, Thomas, 7898 Biedermann, Tilo, 8040 Delgado, Mario, 8369 Hausmann, Barbara, 8211 Blakely,