2011 Cote D'ivoire Preliminary Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Youths in Western Côte D'ivoire

Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer To cite this version: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer. Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobiliza- tion, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre, 36, 2011, African Studies Collection. hal-01649241 HAL Id: hal-01649241 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01649241 Submitted on 27 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, Vol. 36 Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photo: ‘Market scene, Man’ (December 2007) Photographs: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Printed by Ipskamp -

Monthly Humanitarian Report November 2011

Côte d’Ivoire Rapport Humanitaire Mensuel Novembre 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report November 2011 www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives • Celebrating 20 years of coordinated humanitarian action November 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Bulletin | 2 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report Coordination Saves Lives Coordination Saves Lives No. 2 | November 2011 HIGHLIGHTS Voluntary and spontaneous repatriation of Ivorian refugees from Liberia continues in Western Cote d’Ivoire. African Union (AU) delegation visited Duékoué, West of Côte d'Ivoire. Tripartite agreement signed in Lomé between Ivorian and Togolese Governments and the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Voluntary return of internally displaced people from the Duekoue Catholic Church to their areas of origin. World Food Program (WFP) published the findings of the post-distribution survey carried out from 14 to 21 October among 240 beneficiaries in 20 villages along the Liberian border (Toulépleu, Zouan- Hounien and Bin-Houyé). Child Protection Cluster in collaboration with Save the Children and UNICEF published The Vulnerabilities, Violence and Serious violations of Child Rights report. The Special Representative of the UN Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Mrs. Margot Wallström on a six day visit to Côte d'Ivoire. I. GENERAL CONTEXT No major incident has been reported in November except for the clashes that broke out on 1 November between ethnic Guéré people and a group of dozos (traditional hunters). -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

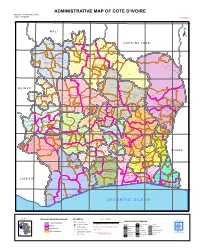

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

7 Cdi Critical Humanitarian Nee

SAMPLE OF ORGANISATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEALS AARREC COSV HT MDM TGH ACF CRS Humedica MEDAIR UMCOR ACTED CWS IA MENTOR UNAIDS ADRA Danchurchaid ILO MERLIN UNDP Africare DDG IMC NCA UNDSS AMI-France Diakonie Emergency Aid INTERMON NPA UNEP ARC DRC Internews NRC UNESCO ASB EM-DH INTERSOS OCHA UNFPA ASI FAO IOM OHCHR UN-HABITAT AVSI FAR IPHD OXFAM UNHCR CARE FHI IR PA (formerly ITDG) UNICEF CARITAS Finnchurchaid IRC PACT UNIFEM CEMIR INTERNATIONAL FSD IRD PAI UNJLC CESVI GAA IRIN Plan UNMAS CFA GOAL IRW PMU-I UNOPS CHF GTZ Islamic RW PU UNRWA CHFI GVC JOIN RC/Germany VIS CISV Handicap International JRS RCO WFP CMA HealthNet TPO LWF Samaritan's Purse WHO CONCERN HELP Malaria Consortium SECADEV World Concern Concern Universal HelpAge International Malteser Solidarités World Relief COOPI HKI Mercy Corps SUDO WV CORDAID Horn Relief MDA TEARFUND ZOA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table I. Summary of Requirements – (grouped by cluster) .................................................................. 3 Table II. Summary of Requirements – (grouped by appealing organisation) ......................................... 3 2. FROM THE FLASH APPEAL 2002 TO THE CONSOLIDATED APPEAL 2007........................................... 4 3. 2008 IN REVIEW ........................................................................................................................................... 7 COORDINATION -

Cote D'ivoire Summary Full Resettlement Plan (Frp)

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : GRID REINFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT COUNTRY : COTE D’IVOIRE SUMMARY FULL RESETTLEMENT PLAN (FRP) Project Team : Mr. R. KITANDALA, Electrical Engineer, ONEC.1 Mr. P. DJAIGBE, Principal Energy Officer ONEC.1/SNFO Mr. M.L. KINANE, Principal Environmental Specialist ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consulting Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. A.RUGUMBA, Director, ONEC Regional Director: Mr. A. BERNOUSSI, Acting Director, ORWA Division Manager: Mr. Z. AMADOU, Division Manager, ONEC.1, 1 GRID REIFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Summary FRP Project Name : GRID REIFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Country : COTE D’IVOIRE Project Number : P-CI-FA0-014 Department : ONEC Division: ONEC 1 INTRODUCTION This document presents the summary Full Resettlement Plan (FRP) of the Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project. It defines the principles and terms of establishment of indemnification and compensation measures for project affected persons and draws up an estimated budget for its implementation. This plan has identified 543 assets that will be affected by the project, while indicating their socio- economic status, the value of the assets impacted, the terms of compensation, and the institutional responsibilities, with an indicative timetable for its implementation. This entails: (i) compensating owners of land and developed structures, carrying out agricultural or commercial activities, as well as bearing trees and graves, in the road right-of-way for loss of income, at the monetary value replacement cost; and (ii) encouraging, through public consultation, their participation in the plan’s planning and implementation. 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND IMPACT AREA 1.1. Project Description and Rationale The Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project seeks to strengthen power transmission infrastructure with a view to completing the primary network, ensuring its sustainability and, at the same time, upgrading its available power and maintaining its balance. -

See Full Prospectus

G20 COMPACT WITHAFRICA CÔTE D’IVOIRE Investment Opportunities G20 Compact with Africa 8°W To 7°W 6°W 5°W 4°W 3°W Bamako To MALI Sikasso CÔTE D'IVOIRE COUNTRY CONTEXT Tengrel BURKINA To Bobo Dioulasso FASO To Kampti Minignan Folon CITIES AND TOWNS 10°N é 10°N Bagoué o g DISTRICT CAPITALS a SAVANES B DENGUÉLÉ To REGION CAPITALS Batie Odienné Boundiali Ferkessedougou NATIONAL CAPITAL Korhogo K RIVERS Kabadougou o —growth m Macroeconomic stability B Poro Tchologo Bouna To o o u é MAIN ROADS Beyla To c Bounkani Bole n RAILROADS a 9°N l 9°N averaging 9% over past five years, low B a m DISTRICT BOUNDARIES a d n ZANZAN S a AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT and stable inflation, contained fiscal a B N GUINEA s Hambol s WOROBA BOUNDARIES z a i n Worodougou d M r a Dabakala Bafing a Bere REGION BOUNDARIES r deficit; sustainable debt Touba a o u VALLEE DU BANDAMA é INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES Séguéla Mankono Katiola Bondoukou 8°N 8°N Gontougo To To Tanda Wenchi Nzerekore Biankouma Béoumi Bouaké Tonkpi Lac de Gbêke Business friendly investment Mont Nimba Haut-Sassandra Kossou Sakassou M'Bahiakro (1,752 m) Man Vavoua Zuenoula Iffou MONTAGNES To Danane SASSANDRA- Sunyani Guemon Tiebissou Belier Agnibilékrou climate—sustained progress over the MARAHOUE Bocanda LACS Daoukro Bangolo Bouaflé 7°N 7°N Daloa YAMOUSSOUKRO Marahoue last four years as measured by Doing Duekoue o Abengourou b GHANA o YAMOUSSOUKRO Dimbokro L Sinfra Guiglo Bongouanou Indenie- Toulepleu Toumodi N'Zi Djuablin Business, Global Competitiveness, Oumé Cavally Issia Belier To Gôh CÔTE D'IVOIRE Monrovia -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Final Performance Evaluation

USAID/OFFICE OF TRANSITION INITIATIVES CÔTE D’IVOIRE TRANSITION INITIATIVE 2 (CITI2) 1 FINAL PERFORMANCE EVALUATION This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by Victor Tanner on behalf of Social Impact. A FINAL PERFORMANCE EVALUATION OF USAID/OTI’S CÔTE D’IVOIRE TRANSITION INITIATIVE 2 (CITI2) April 15, 2016 OTI PDQIII Task Order 10, Activity 4 Q011OAA1500012 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 2 TABLES OF CONTENTS Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Context and Overview ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Cote D'ivoire

1 Cote d’Ivoire Media and telecoms landscape guide August 2011 2 Index Page Introduction..................................................................................................... 3 Media overview................................................................................................ 8 Radio overview................................................................................................17 Radio stations..................................................................................................21 TV overview......................................................................................................52 TV stations.......................................................................................................54 Print media.......................................................................................................58 Main newspapers............................................................................................60 Internet news sites.........................................................................................66 Media resources..............................................................................................67 Traditional channels of communication.......................................................76 Telecoms overview.........................................................................................79 Telecoms companies......................................................................................82 Principal sources............................................................................................87 -

Final Report: International Election Observation Mission to Côte D'ivoire, 2010 Presidential Elections and 2011 Legislative

International Election Observation Mission to Côte d’Ivoire Final Report 2010 Presidential Elections and 2011 Legislative Elections Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. The Carter Center strives to relieve suffering by advancing peace and health worldwide; it seeks to prevent and resolve conflicts, enhance freedom and democracy, and protect and promote human rights worldwide. International Election Observation Mission to Côte d’Ivoire Final Report 2010 Presidential Elections and 2011 Legislative Elections One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 The Appeals Process ......................63 Executive Summary and Recommendations......3 Election-Related Violence ..................65 The Carter Center in Côte d’Ivoire ............3 Certification of Results . .66 Observation Methodology ....................4 Conclusions and Recommendations Conclusions of the Election Observation Mission ..6 Regarding the 2010 Presidential Election.......67 The Carter Center in Côte d’Ivoire — The Carter Center in Côte d’Ivoire — Presidential Election 2010 ..................16 Legislative Elections 2011 . .72 Political Context...........................18 Political Context...........................74 Framework of the Presidential Election ........21 Hijacking of the Election and the Political- Military Crisis ...........................74 Legal Framework ........................21 Boycott of the Front Populaire -

Côte D'ivoire

Niger 8° 7° 6° 5° 4° 3° CÔTE D’IVOIRE The boundaries and names shown and CÔTE the designations used on this map do Sikasso BURKINA National capital D’IVOIRE not imply official endorsement or Regional capital acceptance by the United Nations Bobo-Dioulasso e FASO r Town i 11° Diebougou o 11° Orodara Major airport N B a t a International boundary l MALI g o o L e V e Regional boundary r Banfora a b Main road a Tingrela Railroad Gaoua Goueya San Sokoro kar ani Katoro Kaoura 10° Maniniam Zinguinasso Ouangolodougou 10° Korohara Samatiguila Banda B ma l SAVANES B Bobanie a DENGUELE l c a Moromoro k n Madinani c V Gbeleba o Odienne l Boundiali Ferkessedougou t a I T Seguelo Korhogo r i i e n n g b a Fasselemon o Bouna u GUINEA Bako Paatogo Kiemou Tafire 9° 9° B Gawi Siraodi ou Kineta Fadyadougou Lato M Kakpin a Bandoli Koro r Sonozo a a Kafine oa/Bo Kani h VALLEE DU B o ZANZAN u e Dabakala Boudouyo Santa Touba WORODOUGOU BANDAMA Tanbi BAFING Nandala Mankono Katiola Diaradougou Bondoukau 8° Foungesso 8° C Seguela a v Tanda a Glanle Biankouma Toumbo l l y Beoumi Bouake DIX-HUIT MONTAGNES Zuenoula Sakassou M'Bahiacro Koun Man Vavoua Ba Sunyani Danane N’ZI COMOE HAUT Agnibilekrou Bangolo Daoukro 7° SASSANDRA Bouafle LACS MOYEN 7° COMOE Binhouye Daloa MARAHOUE Yamoussoukro Duekoue Abengourou Dimbokro Sinfra Guiglo Bougouanou Toulepleu Issia Toumodi GHANA Oume MOYENCAVALLY Bebou FROMAGER a i o Zagne Gribouo Gagnoa AGNEBY B n a Tchien Adzope T 6° 6° Agboville Tai Lakota Divo Tiassale Soubre SUD Gueyo SUD BANDAMA COMOE B LIBERIA o u LAGUNES b Aboisso Niebe o Abidjan Grand-Lahou Fish Town BAS SASSANDRA Attoutou Grand-Bassam Braffedon 5° Gazeko 5° Grabo N o n Sassandra o GULF O F GUINEA Barclayville Olodio San-Pedro 0 30 60 90 km Grand Béréby Harper 0 30 60 mi Tabou ATLANTIC OCE A N 8° 7° 6° 5° 4° 3° Map No.