Download (19MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immersion Education Outcomes and the Gaelic Community: Identities and Language Ideologies Among Gaelic Medium-Educated Adults in Scotland

Dunmore, S. S. (2017) Immersion education outcomes and the Gaelic community: identities and language ideologies among Gaelic medium-educated adults in Scotland. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(8), pp. 726-741. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/205747/ Deposited on: 16 December 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Stuart S. Dunmore Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 2016 Immersion education outcomes and the Gaelic community: Identities and language ideologies among Gaelic-medium educated adults in Scotland Abstract: Scholars have consistently theorised that language ideologies Keywords: can influence the ways in which bilingual speakers in minority language Bilingual settings identify and engage with the linguistic varieties available to them. education; Research conducted by the author examined the interplay of language use revitalisation; and ideologies among a purposive sample of adults who started in Gaelic- language medium education during the first years of its availability. Crucially, the ideologies; majority of participants’ Gaelic use today is limited, although notable cultural exceptions were found among individuals who were substantially identities socialised in the language at home during childhood, and a small number of new speakers. In this paper I draw attention to some of the language ideologies that interviewees conveyed when describing their cultural Article identifications with Gaelic. I argue that the ideologies that informants accepted: express seem to militate against their more frequent use of the language 12.10.2016 and their association with the wider Gaelic community. -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Barrow-In-Furness, Cumbria

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria Shelfmark: C1190/11/01 Recording date: 2005 Speakers: Airaksinen, Ben, b. 1987 Helsinki; male; sixth-form student (father b. Finland, research scientist; mother b. Barrow-in-Furness) France, Jane, b. 1954 Barrow-in-Furness; female; unemployed (father b. Knotty Ash, shoemaker; mother b. Bootle, housewife) Andy, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; male; sixth-form student (father b. Barrow-in-Furness, shop sales assistant; mother b. Harrow, dinner lady) Clare, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; female; sixth-form student (father b. Barrow-in-Furness, farmer; mother b. Brentwood, Essex) Lucy, b. 1988 Leeds; female; sixth-form student (father b. Pudsey, farmer; mother b. Dewsbury, building and construction tutor; nursing home activities co-ordinator) Nathan, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; male; sixth-form student (father b. Dalton-in-Furness, IT worker; mother b. Barrow-in-Furness) The interviewees (except Jane France) are sixth-form students at Barrow VI Form College. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♥ see Dictionary of Contemporary Slang (2014) ♦ see Urban Dictionary (online) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased chuffed; happy; made-up tired knackered unwell ill; touch under the weather; dicky; sick; poorly hot baking; boiling; scorching; warm cold freezing; chilly; Baltic◊ annoyed nowty∆; frustrated; pissed off; miffed; peeved -

Jayne Raisborough and Matt Adams: Mockery and Morality

provided by Research Papers in Economics View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Mockery and Morality in Popular Cultural Representations of the White, Working Class by Jayne Raisborough and Matt Adams University of Brighton Sociological Research Online 13(6)2 <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/13/6/2.html> doi:10.5153/sro.1814 Received: 1 Feb 2008 Accepted: 13 Oct 2008 Published: 30 Nov 2008 Abstract We draw on 'new' class analysis to argue that mockery frames many cultural representations of class and move to consider how it operates within the processes of class distinction. Influenced by theories of disparagement humour, we explore how mockery creates spaces of enunciation, which serve, when inhabited by the middle class, particular articulations of distinction from the white, working class. From there we argue that these spaces, often presented as those of humour and fun, simultaneously generate for the middle class a certain distancing from those articulations. The plays of articulation and distancing, we suggest, allow a more palatable, morally sensitive form of distinction-work for the middle-class subject than can be offered by blunt expressions of disgust currently argued by some 'new' class theorising. We will claim that mockery offers a certain strategic orientation to class and to distinction work before finishing with a detailed reading of two Neds comic strips to illustrate what aspects of perceived white, working class lives are deemed appropriate for these functions of mockery. The Neds, are the latest comic-strip family launched by the publishers of children's comics The Beano and The Dandy, D C Thomson and Co Ltd. -

11-20 November Issue

The British Isles Historic Society Heritage, History, Traditions & Customs 11-20 November Issue St. Andrew deeming himself unworthy to be crucified in the same manner as Jesus Christ. Instead, he was nailed St. Andrew has been celebrated upon an X-shaped cross on 30 November 60AD in in Scotland for over a thousand years, Greece, and thus the diagonal cross of the saltire with feasts being held in his honour as was adopted as his symbol, and the last day in far back as the year 1000 AD. November designated his saint day. However, it wasn’t until 1320, According to legend, Óengus II, king of Picts when Scotland’s independence was and Scots, led an army against the Angles, a declared with the signing of The Germanic people that invaded Britain. The Scots Declaration of Arbroath, that he officially became were heavily outnumbered, and Óengus prayed the Scotland’s patron saint. Since then St Andrew has night before battle, vowing to name St. Andrew the become tied up in so much of Scotland. The flag of patron saint of Scotland if they won. Scotland, the St. Andrew’s Cross, was chosen in honour of him. Also, the ancient town of St Andrews On the day of the battle, white clouds formed was named due to its claim of being the final resting an X in the sky. The clouds were thought to place of St. Andrew. represent the X-shaped cross where St. Andrew was crucified. The troops were inspired by the apparent According to Christian teachings, Saint Andrew divine intervention, and they came out victorious was one of Jesus Christ’s twelve disciples. -

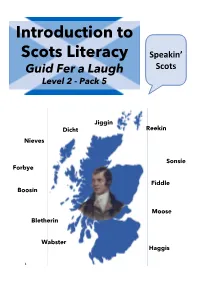

Introduction to Scots Literacy

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution during Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants’ needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scots Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scots Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, shortbread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

An Investigation Into the Environmental Impact of Off-License Premises on Residential Neighbourhoods

An Investigation into the Environmental Impact of Off-license Premises on Residential Neighbourhoods November 2007 Alasdair J. M. Forsyth, Neil Davidson* and Jemma C. Lennox Scottish Centre for Crime & Justice Research The Glasgow Centre for the Study of Violence Glasgow Caledonian University * Now at the Scottish Institute for Policing Research, School of Social Sciences, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN 1 Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Donna Hughes for her assistance during observational fieldwork, Leona Cunningham for assistance during piloting, Stephen Lopez and Catherine McGuinity for help with project administration, Andrew McAuley for providing health statistics, Steve Parkin for information on drug-related litter, Pauline Roberts for graphical advice, Alcohol Focus Scotland for their continued support during this research and the anonymous shop workers who participated in this research. 2 Contents Page Introduction Background 4 Aims 10 Methods Research Design and Procedures 11 Selection of Study Area 15 Results Observations of Neighbourhood Convenience Stores 19 Interviews with Shop Servers 28 Survey of Alcohol-related Detritus 39 Spatial Relationships between Shops and Alcohol-related Incivilities 58 Conclusions Discussion 81 Limitations and Future Research 94 Key Implications and Recommendations 99 Bibliography References 103 Appendices Shop Observation Schedule 114 Shop Server Interview Topic Guide 118 Items of Alcohol-related Detritus Recording Form 119 Neighbourhood Profiles 120 Brand Identified Items of Alcohol-related Detritus 121 3 Introduction Background In recent times there has been a great deal of concern about levels of anti-social behaviour across the UK (Home Office, 2005; House of Commons, 2005; Scottish Parliament, 2003). Several reports have investigated the role of alcohol as a potentially important contributor to this problem (Babb, 2007; Engineer et al, 2003; Finney, 2004; Home Office, 2001; Matthews et al, 2006; Richardson & Budd, 2003; Travis, 2004). -

Introduction SLICE 1

Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe Book series: Standard Language Ideology in Contemporary Europe Editors: Nikolas Coupland and Tore Kristiansen –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1. Tore Kristiansen and Nikolas Coupland (Eds.): Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe. 2011. Tore Kristiansen and Nikolas Coupland (Eds.) Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe NOVUS PRESS OSLO – 2011 Printed with economic support from ..... © Novus AS 2011. Cover: Geir Røsset ISBN: 978-82-7099-659-9 Print: Interface Media as, Oslo. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Novus Press. Acknowledgements This first publication from the SLICE group (Standard Language Ideology in Contemporary Europe) and in its book series has only been possible as a result of much interest and support – which we wish to acknowledge here. The initiative towards the SLICE programme was taken at the LANCHART centre (dgcss.hum.ku.dk). The idea was discussed with members of LANCHART’s International Council at the centre’s annual meeting with the council in 2008, involving Peter Auer, Niko- las Coupland, Paul Kerswill, Dennis R Preston, Mats Thelander, and Helge Sandøy – as well as Peter Garrett as a specially invited ‘sparring partner’. Subsequently, a proposal for a series of Exploratory Workshops was worked out at LANCHART by Frans Gregersen, Tore Kris- tiansen, Shaun Nolan, and Jacob Thøgersen. This volume results from two Exploratory Workshops which were held in Copenhagen, Denmark in February and August of 2009. -

Have No Idea Whether That's True Or Not": Belief and Narrative Event Enactment 3-14 JAMES G

- ~ Volume 9, Number 2 June 1990 CONTENTS KEITH CUNNINGHAM "I Have no Idea Whether That's True or Not": Belief and Narrative Event Enactment 3-14 JAMES G. DELANEY Collecting Folklore in Ireland 15-37 SYLVIA FOX Witch or Wise Women?-women as healers through the ages 39-53 ROBERT PENHALLURICK The Politics of Dialectology 55-68 J.M. KIRK Scots and English in the Speech and Writing of Glasgow 69-83 Reviews 85-124 Index of volumes 8 and 9 125-128 ISSN 0307-7144 LORE AND LANGUAGE The J oumal of The Centre for English Cultural Tradition and Language Editor J.D.A. Widdowson © Sheffield Acdemic Press Ltd, 1990 Copyright is waived where reproduction of material from this Journal is required for classroom use or course work by students. SUBSCRIPTION LORE AND LANGUAGE is published twice annually. Volume 9 (1990) is: Individuals £16.50 or $27.50 Institutions £50.00 or $80.00 Subscriptions and all other business correspondence shuld be sent to Sheffield Academic Press, 343 Fulwood Road, Sheffield S 10 3BP, England. All previous issues are still available. The opinions expressed in this Journal are not necessarily those of the editor or publisher, and are the responsibility of the individual authors. Printed on acid-free paper in Great Britian by The Charlesworth Group, Huddersfield [Lore & Language 9/2 (1990) 3-14] "I Have No Idea Whether That's True or Not": Belief and Narrative Event Enactment Keith Cunningham A great deal of scholarly attention has in recent years been directed toward a group of traditional narratives told in British and Anglo-American cultures1 which have been called "contemporary legend" ,2 "urban legend" ,3 and "modem myth". -

Critical Study

Representing and Rejecting: Vernacular in Fiction with primary focus on James Kelman and Irvine Welsh 1993-94 A Critical Study Submitted by Leon A.C. Qualls for the MPhil in Writing University of South Wales Director of Studies: Rob Middlehurst Date submitted: November 2017 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature Review 2.1 Primary Texts 3 2.2 The Rejection of Standard English and Classical Realism 5 2.3 The Parochial Booker and Literary Separatism 9 3. Analysis 3.1 Putting the ‘fuck’ in Fiction—Kelman’s vernacular 12 3.2 It’s Cool to be a Cunt—The Trainspotting Phenomenon 23 3.3 Fight like You’re Painting the Forth Bridge 29 3.4 Vernacular in related Fiction and its Influence 32 4. Conclusion 40 5. Works Cited 46 Leon A.C. Qualls / 06026273 MPhil in Writing 1. Introduction The writing of my first novel, Hell Mend Me, has been a long, arduous task, involving more rewrites than I care to admit. No different from most authors, I dare say. The idea for the novel was first conceived whilst studying for my BA Creative and Professional Writing. Here was I, a Glaswegian in Wales, hoping to find my writing voice through the channel of standardised English. I was told to write about what I knew, and yet my eagerness to portray what I knew through a voice of insipidness was not entirely apparent until I was asked by a tutor to write a short story using Glaswegian vernacular.1 The response to my newly-found Glaswegian voice was overwhelmingly positive. -

An Overview of Scotland's Linguistic Situation

An Overview of Scotland’s Linguistic Situation Maxime Bailly To cite this version: Maxime Bailly. An Overview of Scotland’s Linguistic Situation. Literature. 2012. dumas-00935160 HAL Id: dumas-00935160 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00935160 Submitted on 23 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. An Overview of Scotland's Linguistic Situation Nom : BAILLY Prénom : Maxime UFR Etudes Anglophones Mémoire de master 1 - 18 crédits Sous la direction de Monsieur Jérôme PUCKICA Année universitaire 2011-2012 1 Contents: Introduction 4 1.The relationship between Scots and English: A short Linguistic History of Scotland 6 1.1. From Anglo-Saxon to ‘Scottis’ ........................................................................................ 8 1.1.1. The early settlers ....................................................................................................... 8 1.1.2. The emergence of 'Anglo-Scandinavian' .................................................................. 9 1.1.3. The feudal system and the rise of 'Scottis' ............................................................. -

Linguistic and Political Backlash and Conformity in Eighteenth-Century Scots

1 ‘An Eye for an Aye’: Linguistic and Political Backlash and Conformity in Eighteenth-Century Scots LING690 Sarah van Eyndhoven Abstract This study examines the effects of social and political changes that were occurring during the eighteenth century in Scotland on the use of written Scots, focussing in particular upon authors who were known to have been for or against the Union of the Parliaments in 1707. In order to capture a holistic representation of the levels of Scots in writing, I explore the proportion of Scots lexemes, compared with their corresponding English lexemes, in a purpose-built corpus containing a range of eighteenth-century texts. This corpus contains both texts that were produced by a general cross- section of Scottish society, and a number of politically-active individuals. I take a quantitative sociolinguistic approach to historical data by utilising statistical techniques that examine linguistic variation in a data-driven manner. This enables a more detailed and empirical exploration of Scots in the eighteenth century, which until now has been largely examined on a descriptive basis only. Using a number of statistical tools that are well suited to historical analyses, such as Variability-based Neighbour Clustering (Gries & Hilpert, 2008), conditional inference trees (Hothorn et al., 2006) and random forests (Breiman, 2001), I have been able to reconstruct both the general patterning of the Scots language over time and the extralinguistic factors encouraging or suppressing its presence in writing. In particular, I compare the use of Scots between the general literate population and political individuals active during this time period. I also explore the effect of the latter’s political sympathies on their language choices, and uncover several new and interesting effects conditioning the levels of Scots in their writings.