Download the Project Report Pdf File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Issue 27 As

Policy & Practice A Development Education Review ISSN: 1748-135X Editor: Stephen McCloskey "The views expressed herein are those of individual authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of Irish Aid." © Centre for Global Education 2018 The Centre for Global Education is accepted as a charity by Inland Revenue under reference number XR73713 and is a Company Limited by Guarantee Number 25290 Contents Editorial Rethinking Critical Approaches to Global and Development Education Sharon Stein 1 Focus Critical History Matters: Understanding Development Education in Ireland Today through the Lens of the Past Eilish Dillon 14 Illuminating the Exploration of Conflict through the Lens of Global Citizenship Education Benjamin Mallon 37 Justice Dialogue for Grassroots Transition Eilish Rooney 70 Perspectives Supporting Schools to Teach about Refugees and Asylum-Seekers Liz Hibberd 94 Empowering more Proactive Citizens through Development Education: The Results of Three Learning Practices Developed in Higher Education Sandra Saúde, Ana Paula Zarcos & Albertina Raposo 109 Nailing our Development Education Flag to the Mast and Flying it High Gertrude Cotter 127 Global Education Can Foster the Vision and Ethos of Catholic Secondary Schools in Ireland Anne Payne 142 Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review i |P a g e Joining the Dots: Connecting Change, Post-Primary Development Education, Initial Teacher Education and an Inter-Disciplinary Cross-Curricular Context Nigel Quirke-Bolt and Gerry Jeffers 163 Viewpoint The Communist -

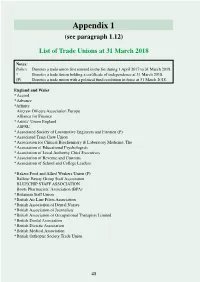

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland 2019-2020

2019-2020 Annual Report of the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland (Covering Period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020). 10-16 Gordon Street Process Colour C: 60 M: 100 Y: 0 Belfast BT1 2LG K: 40 Tel: 028 9023 7773 Pantone Colour 260 Process Colour C: 21 Email: [email protected] M: 26 Y: 61 K: 0 Web: www.nicertoffice.org.uk Pantone Colour 111 TYPEFACE : HELVETICA NEUE First published February 2021 CERTIFICATION OFFICER FOR NORTHERN IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Laid before the Northern Ireland Assembly under paragraph 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 by the Department for the Economy Mr Mike Brennan Permanent Secretary Department for the Economy Netherleigh House Massey Avenue BELFAST BT4 2JP I am required by Article 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to submit to you a report of my activities, as soon as practicable, after the end of each financial year. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. Sarah Havlin LLB Certification Officer for Northern Ireland February 2021 2 Mrs Marie Mallon Chair Labour Relations Agency 2-16 Gordon Street BELFAST BT1 2LG I am required by Article 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to submit to you a report of my activities, as soon as practicable, after the end of each financial year. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. Sarah Havlin LLB Certification Officer for Northern Ireland February 2021 3 CONTENTS Review of the year A summary from the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland . -

Give Us What We Deserve Taking to the Streets for SEND Funding

Willow’s Windrush nightmare Families at breaking point Windy City victories TA sacked due to hostile The impact of knife crime on Chicago teachers on the gains environment. See page 19. our communities. See page 26. of recent strikes. See page 37. July/ August 2019 Your magazine from the National Education Union Give us what we deserve Taking to the streets for SEND funding. See page 7 END OF TERM PREVIEWS FOR SCHOOLS TO ARRANGE A SPECIAL END OF TERM PREVIEW SCREENING* CONTACT [email protected] WITH AND EMILIA SEBASTIAN NICK CRAIG KATE RUPERT ALEX LEE WARWICK SANJEEV ALEXANDER CHRIS DEREK KIM JONES CROFT FROST ROBERTS NASH GRAVES MACQUEEN MACK DAVIS BHASKAR ARMSTRONG ADDISON JACOBI CATTRALL ARE YOUR STUDENTS #TEAMROMAN OR #TEAMCELT? REGISTER FOR A FUN & FREE LEARNING RESOURCE FROM INTO FILM AT WWW.INTOFILM.ORG/HORRIBLE-HISTORIES IN CINEMAS JULY 26 *PREVIEW SCREENING OFFER AVAILABLE FROM MONDAY JULY 8TH ONWARDS. HORRIBLEHISTORIES.MOVIE HORRIBLEHISTORIESTHEMOVIE Educate July/August 2019 Welcome Protestors at the SEND National Crisis demonstration. Photo: Rehan Jamil Willow’s Windrush nightmare Families at breaking point Windy City victories AS Educate goes to press, members of the Conservative Party are still deciding TA sacked due to hostile The impact of knife crime on Chicago teachers on the gains environment. See page 19. our communities. See page 26. of recent strikes. See page 37. who will become the country’s next Prime Minister. July/ August 2019 The fact that candidates in the Tory leadership election have raised the issue of school funding is testament to all the hard work of campaigners to get Your magazine from the National Education Union this issue on the political agenda. -

Our Hero Child Poverty and Marcus Rashford’S Fight for Free Holiday School Meals

Testing times Defend disabled members End period poverty Demanding school safety Ensuring protection for Free sanitary products during Covid-19. See page 6. at-risk educators. See page 22. in schools. See page 26. November/ December 2020 Your magazine from the National Education Union Our hero Child poverty and Marcus Rashford’s fight for free holiday school meals TUC best membership communication print journal 2019 Meeting your School’s Literacy Needs with Expert Training from CLPE Deepen your subject knowledge with CLPE’s professional courses The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) is an independent UK charity dedicated to raising the literacy achievement of children by putting quality literature at the heart of all learning. 100% 100% 99% Inspires the teacher. of people attending of people attending of people attending Inspires a class. The best our day courses our long courses our day courses would recommend rated the training rated their course course I’ve been on. it to someone else as eff ective as eff ective TEACHER ON CLPE TRAINING, 2019 NEW Online Learning from CLPE Our expert teaching team have developed a programme of online learning to provide extra support for your literacy curriculum. The programme will provide staff with evidence based professional development drawing on learning from CLPE’s research and face to face teaching programmes including: • The CLPE Approach to teaching literacy: Using high quality texts at the heart of the curriculum • CLPE Research and Subject Knowledge Series: Planning eff ective provision to ensure progress in reading and writing • Power of Reading Training Online: Developing a broad, rich book based English curriculum across your school This programme of learning will give primary teachers the opportunity to explore CLPE’s high-impact professional development online. -

2020/2021 the Trade Union (Facility Time Publication Requirements)

Trade Union Facility Time – 2020/2021 The Trade Union (Facility Time Publication Requirements) Regulations 2017 came into force on the 1st April 2017. These regulations place a legislative requirement on relevant public sector employers, including local authorities, to collate and publish, on an annual basis, a range of data on the amount and cost of facility time within their organisation. This note includes data required under these Regulations and data required under the Department for Communities and Local Government Transparency Code which took effect on 2nd February 2015. The Regulations require data to be published by function. This detail is set out below. Central Function employees are defined as employees other than those employed in the Education Function of the Council. Education Function employees are defined as persons employed by virtue of section 35(2) of the Education Act 2002 (staffing of community, voluntary controlled, community special and maintained nursery schools). The total cost of trade union facility time across both Central and Education functions for 2020/2021 was £64,903 which represents 0.04% of the authority’s total pay bill. Costs can vary on an annual basis as they are based on the actual salary of the individual representatives. Relevant union officials spent no paid time on trade union activities. 1. Central Function employees 2020/2021 In accordance with the national terms and conditions, the Council recognises the following trade unions for collective bargaining purposes in the Central Function: UNISON GMB UNITE Percentage of time spent No. of FTE on facility time 2018/19: representatives Less than 1% 8 7.43 1- 50% 3 2.28 51 - 99% 0 0.00 100% 2 1.81 Total 13* 11.52* * NB this is the total number and includes new representatives and any ceasing to be representatives during the year There were 13 (11.52 FTE) employees who were trade union representatives employed in the Central Function. -

Schools Told to 'Get Their Act Together'

the million-pound not-so-free schools: book review: bailouts for the true cost of interrogating failing schools gove’s project school training page 3 page 11 page 20 SCHOOLSWEEK.CO.UK FRIDAY, JANUARY 26, 2018 | EDITION 127 PORTER: WHY TEACHERS SHOULD SWAP THEIR CLASSROOMS FOR CELLS PROFILE P16-17 SCHOOLS TOLD TO ‘GET THEIR ACT TOGETHER’ Trusts failing to comply with new Baker Clause requirement PICKING APART Leaders argue there’s been little promotion of new law 2017 GCSE EXAM ALIX ROBERTSON DATA PAGES 3,6-7 @ALIXROBERTSON4 Investigates Page 5 HAVE YOU BOOKED YOUR TICKETS TO THE FESTIVAL OF EDUCATION YET? 21-22 JUNE 2018 BROUGHT TO YOU BY SAVE 20% ON TICKETS BY BOOKING BEFORE THE END OF JAN #EDUCATIONFEST | VISIT EDUCATIONFEST.CO.UK TO BOOK NOW 2 @SCHOOLSWEEK SCHOOLS WEEK FRIDAY, JAN 26, 2018 Edition 127 MEET THE NEWS TEAM schoolsweek.co.uk Shane Laura Experts Mann McInerney MANAGING EDITOR CONTRIBUTING EDITOR (INTERIM) @SHANERMANN @MISS_MCINERNEY TOM [email protected] [email protected] Please inform the Schools Week editor of any errors or issues of concern regarding this publication. RICHMOND Cath Freddie RSC’S OWN SCHOOL Murray Whittaker Page 18 FEATURES EDITOR CHIEF REPORTER GETS AN ‘INADEQUATE‘ @CATHMURRAY_ @FCDWHITTAKER Page 8 [email protected] [email protected] TOM PERRY Tom Alix Mendelsohn Robertson SUB EDITOR SENIOR REPORTER Page 18 @TOM_MENDELSOHN @ALIXROBERTSON4 [email protected] [email protected] THE DIGITAL DEGRADING OF PISA JAN Jess Pippa TESTS Staufenberg -

Maternity Matters

MATERNITY MATTERS July 2018 FOREWORD Maternity Matters is the guide to teachers’ maternity rights for members of the National Education Union (NEU). It aims to explain, as simply as possible, the various maternity and parental rights available to all teachers, whether full or part time. Provisions governing the rights of the majority of women teachers to maternity leave and pay are set out in the Burgundy Book, the national agreement on teachers’ conditions of service in England and Wales. The statutory scheme runs parallel to the Burgundy Book scheme. Significant improvements have been achieved by the NEU in negotiations with a number of local education authorities and academy chains at local level. It is impossible in this guidance to anticipate every potential question about maternity entitlement. Reading the guidance will, however, answer the majority of the questions you are likely to have. If any aspect remains unclear, members in England should contact the AdviceLine on 0345 811 8111 or email https://neu.org.uk/contact-neu- advice-line (contact details set out at Appendix B). Members in Wales should contact NEU Cymru on 029 2046 5000 or email https://neu.org.uk/contact-neu- cymru. If you are taking maternity or adoption leave, or changing your hours for a different reason, please contact NEU Membership to update your details as reduced subscriptions may apply. Call 0345 811 8111 or go to https://neu.org.uk/contact-neu- membership. Please also use this opportunity to update your equality details. Mary Bousted Kevin Courtney Joint General Secretary Joint General Secretary MATERNITY MATTERS – LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS The information, advice and guidance set out by the NEU in this guide concern national legislation and national agreements. -

Democracy's Champion: Albert Shanker and The

DEMOCRACY’S CHAMPION ALBERT SHANKER and the International Impact of the American Federation of Teachers By Eric Chenoweth BOARD OF DIRECTORS Paul E. Almeida Anthony Bryk Barbara Byrd-Bennett Landon Butler David K. Cohen Thomas R. Donahue Han Dongfang Bob Edwards Carl Gershman The Albert Shanker Institute is a nonprofit organization established in 1998 to honor the life and legacy of the late president of the Milton Goldberg American Federation of Teachers. The organization’s by-laws Ernest G. Green commit it to four fundamental principles—vibrant democracy, Linda Darling Hammond quality public education, a voice for working people in decisions E. D. Hirsch, Jr. affecting their jobs and their lives, and free and open debate about Sol Hurwitz all of these issues. John Jackson Clifford B. Janey The institute brings together influential leaders and thinkers from Lorretta Johnson business, labor, government, and education from across the political Susan Moore Johnson spectrum. It sponsors research, promotes discussions, and seeks new Ted Kirsch and workable approaches to the issues that will shape the future of Francine Lawrence democracy, education, and unionism. Many of these conversations Stanley S. Litow are off-the-record, encouraging lively, honest debate and new Michael Maccoby understandings. Herb Magidson Harold Meyerson These efforts are directed by and accountable to a diverse and Mary Cathryn Ricker distinguished board of directors representing the richness of Al Richard Riley Shanker’s commitments and concerns. William Schmidt Randi Weingarten ____________________________________________ Deborah L. Wince-Smith This document was written for the Albert Shanker Institute and does not necessarily represent the views of the institute or the members of its Board EMERITUS BOARD of Directors. -

TUC Directory 2021

2021 CONTENTS SECTION 1 SECTION 4 About the TUC Trade unions Welcome 05 Union statistics 34 Who we are 06 TUC member unions 44 What we do 06 Confederations of unions 90 TUC priorities 2020–21 07 How the TUC works 08 SECTION 5 Committee membership 10 Skills, education and training SECTION 2 Learning through unions 94 TUC people TUC Education 98 Policy staff at Congress House 16 Policy staff in Wales and SECTION 6 the English regions 22 International relations ETUC affiliated unions 104 SECTION 3 ITUC regional organisations 107 TUC services ITUC global union federations 108 Helping unions grow and thrive 26 TUC Aid 110 TUC Information Service 28 TUC publications 28 SECTION 7 Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum 29 Calendar of events 111 TUC Library Collections 31 TUC archive 31 © James Brittain/Hugh Broughton Architects Broughton Brittain/Hugh James © SECTION 1 ABOUT THE TUC BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE WELCOME TO THE 2021 EDITION OF THE TUC DIRECTORY No-one could have foreseen the twin challenges of the global pandemic and consequent recession. We should be proud of the way the trade union movement responded, stepping up to fight the pandemic, demanding action to protect jobs and supporting our members through thick and thin. We showed the importance of unions standing up for working people. We adapted how we work and found new ways to build common purpose, understanding and solidarity when we couldn’t be physically together. We adopted the Organising Pledge that commits us to recruiting new members, seeking new recognitions and supporting a new generation of reps. -

Download South West TUC Directory

South West TUC Directory The Conservatives want to hand over money meant for injury victims to their fat cat mates in the insurance industry. Millions of workers could lose their right to free or affordable representation if the Tories get their way. Oppose them and tell them to stop Visit www.feedingfatcats.co.uk to take action #FeedingFatCats @feedingfatcats #FeedingFatCats is a campaign run by Thompsons Solicitors. Thompsons is proud to stand up for the injured and mistreated. The Conservatives want to hand over money meant for injury SOUTHWESTTUCDIRECTORY victims to their fat cat mates in Welcome to the South West guide. the insurance industry. TUC Directory. The unions listed Millions of workers could lose their right to free or here represent around half a South West TUC affordable representation if the Tories get their way. million members in the South Church House, Church Road, West, covering every aspect of Filton, Bristol BS34 7BD Oppose them and tell them to stop working life. The agreements t 0117 947 0521 unions reach with employers e [email protected] benefit many thousands more. www.tuc.org.uk/southwest twitter: @swtuc Unions provide a powerful voice Regional Secretary at work, a wide range of services Nigel Costley and a movement for change in e [email protected] these hard times of austerity and cut backs. Southern, Eastern and South West Education Officer Unions champion equal Marie Hughes opportunities, promote learning e [email protected] and engage with partners to Secretary develop a sustainable economy Tanya Parker for the South West. -

Authorised Report of the Educational

' Jtittioual (Bstwshm Stnimt. AUTHORISED REPORT EDUCATIONAL CONGRESS, HELD IN THE Town Hall, Manchester, WEDNESDAY and THURSDAY, Nov. 3rd & 4th-, 18G9. Price Two Shilling?, Post Free. Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, London. Cornish : Birmingham and Manchester. National Education Union Offices, City Buildings, Corporation Street, Manchester. 1809. The various Papers contained in this Volume ake printed in Pamphlet Fobm for wide Circulation. Friends of the cause may obtain them in quantities from the g-eneeal Secretary. Ladies and Gentlemen Desirous of Assisting the Cause by Circulating this Report may have Copies (not less than twelve) at a Reduced Price on Application to the General Secretary. Rev. W. Stanyer, M.A., General Secretary. 116, Cheetham Hill, Manchester, December 16, 1869. Maticwal education Union;. AUTHORISED REPORT ' n * HELD IN THE Town Hall, Manchester, WEDNESDAY and THURSDAY, Nov. 3rd & 4th, 1869. Peice Two Shillings, Post Fbee. \ Longmans, Green, Reader, and Ryder, London. Cornish: Birmingham and Manchester. National Education Union Offices, City Buildings. Corporation Street, Manchester. 18 6 9. The Object op the National Education Union is to Secure the Primary Education op every Child by judiciously Supplementing the present Denominational System op National Education. — CONTENTS. Session 5. :— President The Right Hon. the EARL' OF HARROWBY, K.G. Inaugural Address The Right Hon. the Earl of Harrowby, K.G. Report Rev. W. Stanyer, M.A., Gen. Sec. Paper—" What is Education ? comparison between Secular and Denominational Education" Lord Robert Montagu, M.P. Speech , Lord Edward Howard. " Paper—" Religious Liberty in Education Rev. Dr. Barry. Speech Rev. Prebendary Meyrick, M.A. — " Paper " Results of Present System ... W.