Targets As Allies Or Adversaries: an International Framing Perspective on the “Activist's Dilemma”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Turbulent Priests? The Archbishop of Canterbury in contemporary English politics Daniel Gover Theos Friends’ Programme Theos is a public theology think tank which seeks to influence public opinion about the role of faith and belief in society. We were launched in November 2006 with the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. We provide • high-quality research, reports and publications; • an events programme; • news, information and analysis to media companies and other opinion formers. We can only do this with your help! Theos Friends receive complimentary copies of all Theos publications, invitations to selected events and monthly email bulletins. If you would like to become a Friend, please detach or photocopy the form below, and send it with a cheque to Theos for £60. Thank you. Yes, I would like to help change public opinion! I enclose a cheque for £60 made payable to Theos. Name Address Postcode Email Tel Data Protection Theos will use your personal data to inform you of its activities. If you prefer not to receive this information please tick here By completing you are consenting to receiving communications by telephone and email. Theos will not pass on your details to any third party. Please return this form to: Theos | 77 Great Peter Street | London | SW1P 2EZ S: 97711: D: 36701: Turbulent Priests? what Theos is Theos is a public theology think tank which exists to undertake research and provide commentary on social and political arrangements. We aim to impact opinion around issues of faith and belief in The Archbishop of Canterbury society. -

Hymns Ancient and Modern Booksonix Records

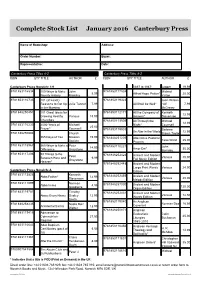

Complete Stock List January 2016 Canterbury Press Name of Bookshop: Address: Order Number: Buyer: Representative: Date: Canterbury Press Titles A-Z Canterbury Press Titles A-Z ISBN QTY TITLE AUTHOR £ ISBN QTY TITLE AUTHOR £ Canterbury Press Norwich: 1-9 1897 to 1987* Jagger 19.99 9781853116834 100 Ways to Make John 9781853117534 Michael 5.99 Alfred Hope Patten* 20.00 Poverty History Madeley Yelton 9781853116735 101 (at Least) 9781853119323 Joan Wilson Reasons to Get Up Julie Tanner 7.99 All Shall be Well* / Alf 7.99 in the Morning McCreary 9781848250451 101 Great Ideas for 9781853112171 All the Company of Kenneth 12.99 Growing Healthy Various 18.99 Heaven* Stevenson Churches 9781853113505 All Through the MIchael 12.99 9781853116230 2000 Years of Michael Night* Counsell 25.00 Prayer* Counsell 9781853119903 Barbara An Altar in the World 12.99 9781848250604 Church Brown Taylor 365 Days of Yes Mission 19.99 9781848251205 Alternative Pastoral Tess Ward 25.00 Society Prayers 9781853115967 365 Ways to Make a Peter 9781853110221 John 14.99 Amor Dei* 30.00 Difference Graystone Burnaby 9781853117206 99 Things to Do Peter 9781848252424 Ancient and Modern Between Here and 9.99 Various 30.00 Graystone Full Music Edition Heaven* 9781848252448 Ancient and Modern Large Print Words Various 24.00 Canterbury Press Norwich: A Edition 9781853113826 Kenneth 9781848252455 Ancient and Modern Abba Father* 12.99 Various 20.00 Stevenson Melody Edition 9781853111099 Norman 9781848257030 Ancient and Modern Abba Imma 4.95 120.00 Goodacre Organ Edition 9781853119781 Timothy 9781848252431 Ancient and Modern Various 12.50 Above Every Name Dudley 12.99 Words Edition Smith 9781853119040 An Anglican 9781848258235 Nadia Bolz Norman Doe 16.99 Accidental Saints 12.99 Covenant Weber 9781848250871 Anglican 9781853119415 Admission to Eucharistic Colin 45.00 Communion 27.50 Liturgies Buchanan Register 1985-2010 9781853116643 Adult Baptism 9781853110450 Anglican Heritage: H. -

Can Art Be Used to Both Celebrate Indian Culture and Keep It Alive?

Can art be used to both celebrate Indian culture and keep it alive? Rianne Karra ID: S17104342 Birmingham City University BA Art and Design 13/01/20 1 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………….3 Chapter 1………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter 2………………………………………………………………………5 Chapter 3.……………………………………………………………………..6 Chapter 4……………………………………………………………………….7-12 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………..13 Bibliography………………………………………………………………….14-17 Appendix………………………………………………………………………..18 2 Introduction This dissertation looks into the importance of both celebrating and keeping Indian culture alive in the UK today and how art can be used to do that. Celebrating the diversity and difference within the UK, that came as a part of immigration. Chapter one, addresses how the current situation of Britain, has left us to believe if Britain is as diverse as we imagine it to be, with issues like Brexit allowing for hate crimes and discrimination. Chapter two, reflects how Britain has become home to minority communities through post war immigration and highlights the issues of low minority participation in the arts but how art can be used to sustain Indian culture. By doing so, might prevent assimilation from occurring which chapter three looks into. By looking at the work of two British Asian artists through case studies: Chila Kumari Burman and Navi Kaur, who use their practice to display culture through community and celebrate difference. As a person of British Asian heritage, the idea of identity can be difficult to define, as it is made up of multiple aspects, and two very different components, Britishness and our ancestral culture. Our culture has been carried between generations, and continued on within Britain by us and the beliefs we uphold. -

Churchof England

THE TaTakinkingtgthehe CHURCHOF GospeGospelonlon ENGLAND tourtour Newspaper p9p9 25.05.18 £1.50 No: 6434 Established in 1828 AVAILABLE ON GooglePlay iTunes DIGEST Churches unitetoremember Youth Trust boost AYoung Leaders Award scheme runbythe Archbishop of York is to be expanded fatefulManchesterbombing nationally. CHURCHES in Manchester St Ann’s Squarewas the focal The Allchurches Trust this wereatthe centreofevents point for people’s grief when an week awarded agrant of over this weekmarking the first estimated 300,000 floral tributes £500,000 to the Archbishop of anniversaryofthe bombing and gifts wereleft in the Square. York Youth Trust to enable the in Manchester Arena. This year the flower festival expansion. The Bishop of Manchester, featured displays created by 23 Dr John Sentamu founded the theRtRev David Walker,said: groups of flower arrangers from Trust in 2009 with the aim of “At the heartofour commemo- around the country empowering anew generation rations will be those families Each of the 25 floral displays of young leaders. So far over mostaffectedbythe attack. We depicted an aspect of Manches- 63,000 young people across the will gatherwith them, first in ter.They included titles such as North of England have benefit- the cathedral and later outside ‘A City United’ sponsored by ted from the scheme. the Town Halland in St Ann’s Manchester City and Manches- Square. We will let them know ter United Football Clubs, ‘Suf- Kirkbacks same-sex theyare not forgotten, andthat fragette City’, a‘City of Prayer ourcommitment to them, and Contemplation’ and ‘Coro- marriage through word, prayer and nation Street’, complete with action, is not diminished by a pigeon and Minnie Caldwell’s year’s passing.” Bobby the cat. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abbott, Edwin A., The Kernel and the Husk: Letters on Spiritual Christianity, by the Author of “Philochristus” and “Onesimus”, London: Macmillan, 1886. Adams, Dickenson W. (ed.), The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Second Series): Jefferson’s Extracts from the Gospels, Ruth W. Lester (Assistant ed.), Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983. Addis, Cameron, Jefferson’s Vision for Education, 1760–1845, New York: Peter Lang, 2003. Adorno, Theodore W., and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment, John Cumming (trans.), London: Allen Lane, 1973. Agrippa, Heinrich Cornelius, The Vanity of the Arts and Sciences, London: Printed by R. E. for R. B. and Are to Be Sold by C. Blount, 1684. Albertan-Coppola, Sylviane, ‘Apologetics’, in Catherine Porter (trans.), Alan Charles Kors (ed.), The Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment (vol. 1 of 4), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 58–63. Alexander, Gerhard (ed.), Apologie oder Schutzschrift für die vernünfti- gen Verehrer Gottes/Hermann Samuel Reimarus (2 vols.), im Auftrag der Joachim-Jungius-Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Hamburg, Frankfurt: Insel, 1972. ———, Auktionskatalog der Bibliothek von Hermann Samuel Reimarus: alphabe- tisches Register, Hamburg: Joachim-Jungius-Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften, 1980. Alexander, H. G. (ed.), The Leibniz-Clarke Correspondence: Together with Extracts from Newton’s “Principia” and “Opticks”, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1956. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 375 J. C. P. Birch, Jesus in an Age of Enlightenment, Christianities in the Trans-Atlantic World, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51276-5 376 BIBLIOGRAPHY Allegro, John M., The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross: A Study of the Nature and Origins of Christianity Within the Fertility Cults of the Ancient Near East, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1970. -

The Gove Bible Versus the Occupy Bible." Harnessing Chaos: the Bible in English Political Discourse Since 1968

Crossley, James G. "The Gove Bible Versus the Occupy Bible." Harnessing Chaos: The Bible in English Political Discourse Since 1968. London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2014. 242–276. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567659347.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 04:52 UTC. Copyright © James G. Crossley 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Chapter 9 THE GOVE BIBLE VERSUS THE OCCUPY BIBLE 1. 1611 after 2008: The Bible in an Age of Coalition The 2008 recession – itself a result of longer-term issues in neoliberal deregulation – made its near inevitable impact on British party-politics. A strong case is often made that it cost Gordon Brown and Labour the 2010 election, though the new Coalition government showed that there was not a strong alternative for an outright winner. Tellingly, the Thatcherite and neoliberal rhetoric was intensi¿ed, particularly in the form of public sector cuts, alongside a decreasing popular respect for welfare, as the key tenets of Thatcherism became increasingly embedded in younger generations (see Chapter 4). However, political and public discourse also witnessed an increasing social liberalism on issues such as gender equality and gay rights.1 As some vocal and sizeable Tory opposi- tion to same-sex marriage continued to show (more Tories voted against the bill than for it), such social liberalism is not typically part of traditional Conservatism but it was, nevertheless, brought in by David Cameron and gained degrees of support from leading Tories touted as future Prime Ministers, Boris Johnson and Michael Gove. -

Aldenham-Newsletter-August-2021

LET’S KEEP YOU UP TO We are sorry to have to tell you that we have DATE WITH THE made the decision to postpone this year’s Art Festival until 2022. LATEST NEWS We did not make this decision lightly but with all the uncertainty around at the moment we Our weekly information sheet want to ensure the safety of everybody and is sent by email as well as being make certain that the huge amount of work available in church on Sundays. and money that goes into staging the event is It tells you what is happening at not wasted. church each week; recorded The event will return services, times of services and bigger and better next year! other news as well. It is the ideal way to keep up to date. If you are not already receiving these please let us know your email address by sending it to [email protected] (You can opt out at any time.) “Chosen” (Lost and found between Christianity and Judaism) “Chosen” is the title of a new book by Giles Fraser and published in May this year. You might have heard of Giles Fraser, an Anglican priest whose voice is sometimes heard on Radio 4’s ‘Thought for the Day’. He is usually thought- provoking and can be controversial in some of his views. He certainly took a very strong stand when he was Canon Chancellor of St. Paul’s Cathedral in 2011, in contrast with many of his colleagues. This was at the time of the financial crisis when peaceful protesters camped out around the cathedral. -

St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul’s Cathedral This article is about St Paul’s cathedral in London, sionary saints Fagan, Deruvian, Elvanus, and Medwin. England. For other cathedrals of the same name, see St. None of that is considered credible by modern histori- Paul’s Cathedral (disambiguation). ans but, although the surviving text is problematic, ei- ther Bishop Restitutus or Adelphius at the 314 Council of Arles seems to have come from Londinium.[5] The lo- St Paul’s Cathedral, London, is an Anglican cathedral, the seat of the Bishop of London and the mother church cation of Londinium’s original cathedral is unknown. The present structure of St Peter upon Cornhill was designed of the Diocese of London. It sits at the top of Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the City of London. Its dedica- by Christopher Wren following the Great Fire in 1666 but tion to Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church it stands upon the highest point in the area of old Lon- on this site, founded in AD 604.[1] The present church, dinium and medieval legends tie it to the city’s earliest dating from the late 17th century, was designed in the Christian community. In 1999, however, a large and or- nate 5th-century building on Tower Hill was excavated, English Baroque style by Sir Christopher Wren. Its con- [8][9] struction, completed within Wren’s lifetime, was part of which might have been the city’s cathedral. a major rebuilding programme which took place in the The Elizabethan antiquarian William Camden argued city after the Great Fire of London.[2] that a temple to the goddess Diana had stood during Roman times on the site occupied by the medieval St The cathedral is one of the most famous and most recog- [10] nisable sights of London, with its dome, framed by the Paul’s cathedral. -

An Activist Religiosity? Exploring Christian Support for the Occupy Movement

An activist religiosity? Exploring Christian support for the Occupy movement Whilst Christian involvement in progressive social movements and activism is increasingly recognised, this literature has rarely gone beyond conceptualising religion as a resource to instead consider the ways in which individual activists may articulate their religious identity and how this intersects with the political. Based on ten in-depth interviews with Christian supporters of the Occupy movement, this study offers an opportunity to respond to this gap by exploring the rich meaning-making processes of these activists. The article suggests, firstly, that the location of the London Occupy camp outside St Paul’s Cathedral was of central importance in bringing the Christian Occupiers’ religio- political identities to the foreground, their Christianity being defined in opposition to that represented by St Paul’s. The article then goes on to explore the religio-political meaning-making of the Christian Occupiers, and introduces the term “activist religiosity” as a way of understanding how religion and politics were articulated, and enacted, in similar ways. Indeed, religion and politics became considerably entangled and intertwined, rendering theoretical frameworks that conceptualise religion as a resource increasingly inappropriate. The features of this activist religiosity include: post-institutional identities; a dislike of categorisation; and, centrally, the notion of “doings” – a predominant focus upon engaged, active involvement. Key words: Christianity, social movements, Occupy, activism, religious identity Setting the scene In the early hours of the morning on 28 February 2012, five people gathered to pray on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral. The eviction of the Occupy camp that had been located outside the Cathedral for over four months had begun shortly after midnight and only a few protestors remained. -

3. Political Receptions of the Bible Since 1968 10 A

SCRIPTURAL TRACES: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE RECEPTION AND INFLUENCE OF THE BIBLE 2 Editors Claudia V. Camp, Texas Christian University W. J. Lyons, University of Bristol Andrew Mein, Westcott House, Cambridge Editorial Board Michael J. Gilmour, David Gunn, James Harding, Jorunn Økland Published under LIBRARY OF NEW TESTAMENT STUDIES 506 Formerly Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series Editor Mark Goodacre Editorial Board John M. G. Barclay, Craig Blomberg, R. Alan Culpepper, James D. G Dunn, Craig A. Evans, Stephen Fowl, Robert Fowler, Simon J. Gathercole, John S. Kloppenborg, Michael Labahn, Robert Wall, Steve Walton, Robert L. Webb, Catrin H. Williams HARNESSING CHAOS The Bible in English Political Discourse Since 1968 James G. Crossley LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury is a registered trade mark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 © James G. Crossley, 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. James G. Crossley has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identi¿ed as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. -

To Fulfil the Law: Evangelism, Legal Activism, and Public Christianity in Contemporary England

The London School of Economics and Political Science To fulfil the law: evangelism, legal activism, and public Christianity in contemporary England Méadhbh McIvor A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, May 2016 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare this thesis consists of 99,997 words. 2 Abstract This thesis contributes to the ethnographic corpus by charting the contested place of ‘public’ Christianity in contemporary England, which I explore through the rise of conservative Christian political activism and Christian interest litigation in the English courts. Based on twenty-two months of dual-sited fieldwork split between a Christian lobby group and a conservative evangelical church, it is unique in putting the experiences of religious activists at the legal coalface in direct conversation with (one subsection of) the conservative Christian community they appeal to for spiritual and financial support. -

Parish Link” Magazine for the Churn Valley Benefice

“A to Z of Church Terminology” by the Revd Arthur Champion First published between May 2015 and November 2017 in “Parish Link” magazine for the Churn Valley Benefice Advent Jesus Sin Atonement Judgement Salvation Archdeacon Justification Sacrament Baptism Kingdom Theology Benefice Koinonia Thirty-Nine Articles Blessing Knights Templar Trinity Christ (ians) Lectionary Unction, extreme Church Lecto Divina Undercroft Creed Liturgy Unity Deacon Mass Vestments Devil Minister Vicar Diocese Monstrance Vocation Eternal life Nave Witness Eucharist Neighbour Wittenburg Evil Nestorianism Worship Faith Omnipotent, “X” Omnipresence and Omniscience Filioque Oblation Xerxes 1 Forgiveness Ordination Xmas God Parousia Yahweh Gospel Prayer Year’s mind Grace Protestantism Yeshua Heaven “Q” source Zephaniah Hell Quadrilateral Zionism Holy Quinquennial inspection Zurich Agreement Incarnation Rapture Immortality Repentance Incumbent Resurrection Advent Advent is a season of expectation and preparation, as the Church prepares to celebrate the coming (adventus) of Christ in his incarnation, and also looks ahead to his final advent as judge at the end of time. The readings and liturgies not only direct us towards Christ’s birth; they also challenge the modern reluctance to confront the theme of divine judgement. The lighting of candles on an Advent wreath was imported into Britain from northern Europe in the nineteenth century, and is now a common practice. The first Sunday of Advent is the first Sunday of the Christian year. This is usually the last Sunday in November or the first Sunday in December. By the way the last Sunday of the Christian year is known as “Christ the King” or “the Sunday next before Advent”. Further reading: Common Worship: Times and Seasons; “Celebrate the Christian Story” by Michael Perham Atonement The word atonement is used in Christian theology to describe what is achieved by the death of Jesus.