Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: an Anglican Perspective on State Education

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1995 The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education George Sochan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sochan, George, "The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education" (1995). Dissertations. 3521. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1995 George Sochan LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CULTURAL ROLE OF CHRISTIANITY IN ENGLAND, 1918-1931: AN ANGLICAN PERSPECTIVE ON STATE EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY GEORGE SOCHAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1995 Copyright by George Sochan Sochan, 1995 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION • ••.••••••••••.•••••••..•••..•••.••.•• 1 II. THE CALL FOR REFORM AND THE ANGLICAN RESPONSE ••.• 8 III. THE FISHER ACT •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 35 IV. NO AGREEMENT: THE FAILURE OF THE AMENDING BILL •. 62 v. THE EDUCATIONAL LULL, 1924-1926 •••••••••••••••• 105 VI. THE HADOW REPORT ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 135 VII. THREE FAILED BILLS, THEN THE DEPRESSION •••••••• 168 VIII. CONCLUSION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 218 BIBLIOGRAPHY •••••••••.••••••••••.••.•••••••••••••••••.• 228 VITA ...........................................•....... 231 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since World War II, beginning especially in the 1960s, considerable work has been done on the history of the school system in England. -

Scottish Episcopal Institute Journal

Scottish Episcopal Institute Journal Summer 2021 — Volume 5.2 A quarterly journal for debate on current issues in the Anglican Communion and beyond Scottish Episcopal Institute Journal Volume 5.2 — Summer 2021 — ISSN 2399-8989 ARTICLES Introduction to the Summer Issue on Scottish Episcopal Theologians Alison Peden 7 William Montgomery Watt and Islam Hugh Goddard 11 W. H. C. Frend and Donatism Jane Merdinger 25 Liberal Values under Threat? Vigo Demant’s The Religious Prospect 80 Years On Peter Selby 33 Donald MacKinnon’s Moral Philosophy in Context Andrew Bowyer 49 Oliver O’Donovan as Evangelical Theologian Andrew Errington 63 Some Scottish Episcopal Theologians and the Arts Ann Loades 75 Scottish Episcopal Theologians of Science Jaime Wright 91 Richard Holloway: Expectant Agnostic Ian Paton 101 SCOTTISH EPISCOPAL INSTITUTE JOURNAL 3 REVIEWS Ann Loades. Grace is not Faceless: Reflections on Mary Reviewed by Alison Jasper 116 Hannah Malcolm and Contributors. Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church Reviewed by James Currall 119 David Fergusson and Mark W. Elliott, eds. The History of Scottish Theology, Volume I: Celtic Origins to Reformed Orthodoxy Reviewed by John Reuben Davies 121 Stephen Burns, Bryan Cones and James Tengatenga, eds. Twentieth Century Anglican Theologians: From Evelyn Underhill to Esther Mombo Reviewed by David Jasper 125 Nuria Calduch-Benages, Michael W. Duggan and Dalia Marx, eds. On Wings of Prayer: Sources of Jewish Worship Reviewed by Nicholas Taylor 127 Al Barrett and Ruth Harley. Being Interrupted: Reimagining the Church’s Mission from the Outside, In Reviewed by Lisa Curtice 128 AUTISM AND LITURGY A special request regarding a research project on autism and liturgy Dr Léon van Ommen needs your help for a research project on autism and liturgy. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

198J. M. Thornton Phd.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Thornton, Joanna Margaret (2015) Government Media Policy during the Falklands War. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/50411/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Government Media Policy during the Falklands War A thesis presented by Joanna Margaret Thornton to the School of History, University of Kent In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History University of Kent Canterbury, Kent January 2015 ©Joanna Thornton All rights reserved 2015 Abstract This study addresses Government media policy throughout the Falklands War of 1982. It considers the effectiveness, and charts the development of, Falklands-related public relations’ policy by departments including, but not limited to, the Ministry of Defence (MoD). -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Rene Matthew Kollar. Permanent Address: Saint Vincent Archabbey, 300 Fraser Purchase Road, Latrobe, PA 15650. E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 724-805-2343. Fax: 724-805-2812. Date of Birth: June 21, 1947. Place of Birth: Hastings, PA. Secondary Education: Saint Vincent Prep School, Latrobe, PA 15650, 1965. Collegiate Institutions Attended Dates Degree Date of Degree Saint Vincent College 1965-70 B. A. 1970 Saint Vincent Seminary 1970-73 M. Div. 1973 Institute of Historical Research, University of London 1978-80 University of Maryland, College Park 1972-81 M. A. 1975 Ph. D. 1981 Major: English History, Ecclesiastical History, Modern Ireland. Minor: Modern European History. Rene M. Kollar Page 2 Professional Experience: Teaching Assistant, University of Maryland, 1974-75. Lecturer, History Department Saint Vincent College, 1976. Instructor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1981. Assistant Professor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1982. Adjunct Professor, Church History, Saint Vincent Seminary, 1982. Member, Liberal Arts Program, Saint Vincent College, 1981-86. Campus Ministry, Saint Vincent College, 1982-86. Director, Liberal Arts Program, Saint Vincent College, 1983-84. Associate Professor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1985. Honorary Research Fellow King’s College University of London, 1987-88. Graduate Research Seminar (With Dr. J. Champ) “Christianity, Politics, and Modern Society, Department of Christian Doctrine and History, King’s College, University of London, 1987-88. Rene M. Kollar Page 3 Guest Lecturer in Modern Church History, Department of Christian Doctrine and History, King’s College, University of London, 1988. Tutor in Ecclesiastical History, Ealing Abbey, London, 1989-90. Associate Editor, The American Benedictine Review, 1990-94. -

Time for Reflection

All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group TIME FOR REFLECTION A REPORT OF THE ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY HUMANIST GROUP ON RELIGION OR BELIEF IN THE UK PARLIAMENT The All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group acts to bring together non-religious MPs and peers to discuss matters of shared interests. More details of the group can be found at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmallparty/190508/humanist.htm. This report was written by Cordelia Tucker O’Sullivan with assistance from Richy Thompson and David Pollock, both of Humanists UK. Layout and design by Laura Reid. This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the Group. © All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group, 2019-20. TIME FOR REFLECTION CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 INTRODUCTION 6 Recommendations 7 THE CHAPLAIN TO THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS 8 BISHOPS IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 10 Cost of the Lords Spiritual 12 Retired Lords Spiritual 12 Other religious leaders in the Lords 12 Influence of the bishops on the outcome of votes 13 Arguments made for retaining the Lords Spiritual 14 Arguments against retaining the Lords Spiritual 15 House of Lords reform proposals 15 PRAYERS IN PARLIAMENT 18 PARLIAMENT’S ROLE IN GOVERNING THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND 20 Parliamentary oversight of the Church Commissioners 21 ANNEX 1: FORMER LORDS SPIRITUAL IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 22 ANNEX 2: THE INFLUENCE OF LORDS SPIRITUAL ON THE OUTCOME OF VOTES IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 24 Votes decided by the Lords Spiritual 24 Votes decided by current and former bishops 28 3 All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group FOREWORD The UK is more diverse than ever before. -

Hymns Ancient and Modern Booksonix Records

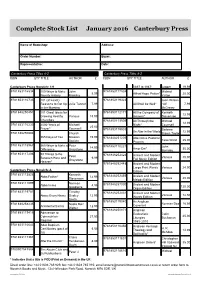

Complete Stock List January 2016 Canterbury Press Name of Bookshop: Address: Order Number: Buyer: Representative: Date: Canterbury Press Titles A-Z Canterbury Press Titles A-Z ISBN QTY TITLE AUTHOR £ ISBN QTY TITLE AUTHOR £ Canterbury Press Norwich: 1-9 1897 to 1987* Jagger 19.99 9781853116834 100 Ways to Make John 9781853117534 Michael 5.99 Alfred Hope Patten* 20.00 Poverty History Madeley Yelton 9781853116735 101 (at Least) 9781853119323 Joan Wilson Reasons to Get Up Julie Tanner 7.99 All Shall be Well* / Alf 7.99 in the Morning McCreary 9781848250451 101 Great Ideas for 9781853112171 All the Company of Kenneth 12.99 Growing Healthy Various 18.99 Heaven* Stevenson Churches 9781853113505 All Through the MIchael 12.99 9781853116230 2000 Years of Michael Night* Counsell 25.00 Prayer* Counsell 9781853119903 Barbara An Altar in the World 12.99 9781848250604 Church Brown Taylor 365 Days of Yes Mission 19.99 9781848251205 Alternative Pastoral Tess Ward 25.00 Society Prayers 9781853115967 365 Ways to Make a Peter 9781853110221 John 14.99 Amor Dei* 30.00 Difference Graystone Burnaby 9781853117206 99 Things to Do Peter 9781848252424 Ancient and Modern Between Here and 9.99 Various 30.00 Graystone Full Music Edition Heaven* 9781848252448 Ancient and Modern Large Print Words Various 24.00 Canterbury Press Norwich: A Edition 9781853113826 Kenneth 9781848252455 Ancient and Modern Abba Father* 12.99 Various 20.00 Stevenson Melody Edition 9781853111099 Norman 9781848257030 Ancient and Modern Abba Imma 4.95 120.00 Goodacre Organ Edition 9781853119781 Timothy 9781848252431 Ancient and Modern Various 12.50 Above Every Name Dudley 12.99 Words Edition Smith 9781853119040 An Anglican 9781848258235 Nadia Bolz Norman Doe 16.99 Accidental Saints 12.99 Covenant Weber 9781848250871 Anglican 9781853119415 Admission to Eucharistic Colin 45.00 Communion 27.50 Liturgies Buchanan Register 1985-2010 9781853116643 Adult Baptism 9781853110450 Anglican Heritage: H. -

Carina Trimingham -V

Neutral Citation Number: [2012] EWHC 1296 (QB) Case No: HQ10D03060 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 24/05/2012 Before: THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: Carina Trimingham Claimant - and - Associated Newspapers Limited Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Matthew Ryder QC & William Bennett (instructed by Mishcon de Reya) for the Claimant Antony White QC & Alexandra Marzec (instructed by Reynolds Porter Chamberlain LLP) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 23,24,25,26,27 April 2012 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. ............................. THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT Trimingham v. ANL Approved Judgment Mr Justice Tugendhat : 1. By claim form issued on 11 August 2010 the Claimant (“Ms Trimingham”) complained that the Defendant had wrongfully published private information concerning herself in eight articles. 2. Mr Christopher Huhne MP had been re-elected as the Member of Parliament for Eastleigh in Hampshire at the General Election held in May 2010, just over a month before the first of the articles complained of. He became Secretary of State for Energy in the Coalition Government. He was one of the leading figures in the Government and in the Liberal Democrat Party. In 2008 Ms Trimingham and Mr Huhne started an affair, unknown to both Mr Huhne’s wife, Ms Pryce, and Ms Trimingham’s civil partner. By 2008 Mr Huhne had become the Home Affairs spokesman for the Liberal Democrats. -

Anglican Church and the Development of Pentecostalism in Igboland

ISSN 2239-978X Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol. 3 No. 10 ISSN 2240-0524 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2013 Anglican Church and the Development of Pentecostalism in Igboland Benjamin C.D. Diara Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka- Nigeria Nche George Christian Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka- Nigeria Doi:10.5901/jesr.2013.v3n10p43 Abstract The Anglican mission came into Igboland in the last half of the nineteenth century being the first Christian mission to come into Igboland, precisely in 1857, with Onitsha as the first spot of missionary propagation. From Onitsha the mission spread to other parts of Igboland. The process of the spread was no doubt, marked with the demonstration of the power of the Holy Spirit; hence the early CMS missionaries saw the task of evangelizing Igboland as something that could not have been possible without the victory of the Holy Spirit over the demonic forces that occupied Igboland by then. The objective of this paper is to historically investigate the claim that the presence of the Anglican Church in Igboland marked the origin of Pentecostalism among the Igbo. The method employed in this investigation was both analytical and descriptive. It was discovered that the Anglican mission introduced Pentecostalism into Igboland through their charismatic activities long before the churches that claim exclusive Pentecostalism came, about a century later. The only difference is that the original Anglican Pentecostalism was imbued in their Evangelical tradition as opposed to the modern Pentecostalism which is characterized by seemingly excessive emotional and ecstatic tendencies without much biblical anchorage. -

Bad News for Disabled People: How the Newspapers Are Reporting Disability

Strathclyde Centre for Disability Research and Glasgow Media Unit Bad News for Disabled People: How the newspapers are reporting disability In association with: Contents PAGE 1. Acknowledgements 2 2. Author details 3 3. Main findings 4 4. Summary 6 Part 2 5. Introduction 16 6. Methodology and Design 18 6.1 Content analysis 18 6.2 Audience reception analysis 20 7. Content analysis:Results 22 7.1 Political discussion and critiques of policy 22 7.2 Changes in the profile of disability coverage and ‘sympathetic’ portrayals 32 7.3 Changes in the profile of representations of the ‘undeserving’ disability claimant 38 8. Audience reception analysis 59 8.1 How is disability reported in the media 59 8.2 Views on disabled people 62 8.3 Views on benefits and benefit claimants 64 8.4 Views on government policy 67 9. Conclusion 69 10. References 73 Appendix 1. Coding schedule 80 Appendix 2. Detailed descriptors for coding and analysis 85 1 Acknowledgements This research was commissioned by Inclusion London and their financial sponsorship and administrative backing is gratefully recognised. In particular we would like to acknowledge the help and collaborative support of Anne Kane who provided us with very valuable and helpful advice throughout the research and had a significant input in the drafting of the final report. We would also like to thank the following researchers who worked in the Glasgow Media Group and who tirelessly, carefully and painstakingly undertook the content analysis of the media: Stevie Docherty, Louise Gaw, Daniela Latina, Colin Macpherson, Hannah Millar and Sarah Watson. We are grateful to Allan Sutherland and Jo Ferrie for their contributions to the data collection. -

The Conservative Parliamentary Party the Conservative Parliamentary Party

4 Philip Cowley and Mark Stuart The Conservative parliamentary party The Conservative parliamentary party Philip Cowley and Mark Stuart 1 When the Conservative Party gathered for its first party conference since the 1997 general election, they came to bury the parliamentary party, not to praise it. The preceding five years had seen the party lose its (long-enjoyed) reputation for unity, and the blame for this was laid largely at the feet of the party’s parliamentarians.2 As Peter Riddell noted in The Times, ‘speaker after speaker was loudly cheered whenever they criticised the parliamentary party and its divisions’.3 It was an argument with which both the outgoing and incoming Prime Ministers were in agreement. Just before the 1997 general election, John Major confessed to his biographer that ‘I love my party in the country, but I do not love my parliamentary party’; he was later to claim that ‘divided views – expressed without restraint – in the parliamentary party made our position impossible’.4 And in his first address to the massed ranks of the new parliamentary Labour Party after the election Tony Blair drew attention to the state of the Conservative Party: Look at the Tory Party. Pause. Reflect. Then vow never to emulate. Day after day, when in government they had MPs out there, behaving with the indiscipline and thoughtlessness that was reminiscent of us in the early 80s. Where are they now, those great rebels? His answer was simple: not in Parliament. ‘When the walls came crashing down beneath the tidal wave of change, there was no discrimination between those Tory MPs. -

Download (2260Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/4527 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. God and Mrs Thatcher: Religion and Politics in 1980s Britain Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Liza Filby University of Warwick University ID Number: 0558769 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. ……………………………………………… Date………… 2 Abstract The core theme of this thesis explores the evolving position of religion in the British public realm in the 1980s. Recent scholarship on modern religious history has sought to relocate Britain‟s „secularization moment‟ from the industrialization of the nineteenth century to the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s. My thesis seeks to add to this debate by examining the way in which the established Church and Christian doctrine continued to play a central role in the politics of the 1980s. More specifically it analyses the conflict between the Conservative party and the once labelled „Tory party at Prayer‟, the Church of England. Both Church and state during this period were at loggerheads, projecting contrasting visions of the Christian underpinnings of the nation‟s political values. The first part of this thesis addresses the established Church.