An Activist Religiosity? Exploring Christian Support for the Occupy Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Turbulent Priests? The Archbishop of Canterbury in contemporary English politics Daniel Gover Theos Friends’ Programme Theos is a public theology think tank which seeks to influence public opinion about the role of faith and belief in society. We were launched in November 2006 with the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. We provide • high-quality research, reports and publications; • an events programme; • news, information and analysis to media companies and other opinion formers. We can only do this with your help! Theos Friends receive complimentary copies of all Theos publications, invitations to selected events and monthly email bulletins. If you would like to become a Friend, please detach or photocopy the form below, and send it with a cheque to Theos for £60. Thank you. Yes, I would like to help change public opinion! I enclose a cheque for £60 made payable to Theos. Name Address Postcode Email Tel Data Protection Theos will use your personal data to inform you of its activities. If you prefer not to receive this information please tick here By completing you are consenting to receiving communications by telephone and email. Theos will not pass on your details to any third party. Please return this form to: Theos | 77 Great Peter Street | London | SW1P 2EZ S: 97711: D: 36701: Turbulent Priests? what Theos is Theos is a public theology think tank which exists to undertake research and provide commentary on social and political arrangements. We aim to impact opinion around issues of faith and belief in The Archbishop of Canterbury society. -

Addressing Fundamentalism by Legal and Spiritual Means

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE Addressing Fundamentalism by Legal and Spiritual Means By Dan Wessner Religion and Humane Global Governance by Richard A. Falk. New York: Palgrave, 2001. 191 pp. Gender and Human Rights in Islam and International Law: Equal before Allah, Unequal before Man? by Shaheen Sardar Ali. The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 2000. 358 pp. Religious Fundamentalisms and the Human Rights of Women edited by Courtney W. Howland. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999. 326 pp. The Islamic Quest for Democracy, Pluralism, and Human Rights by Ahmad S. Moussalli. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001. 226 pp. The post-Cold War era stands at a crossroads. Some sort of new world order or disorder is under construction. Our choice to move more toward multilateralism or unilateralism is informed well by inter-religious debate and international law. Both disciplines rightly challenge the “post- Enlightenment divide between religion and politics,” and reinvigorate a spiritual-legal dialogue once thought to be “irrelevant or substandard” (Falk: 1-8, 101). These disciplines can dissemble illusory walls between spiritual/sacred and material/modernist concerns, between realpolitik interests and ethical judgment (Kung 1998: 66). They place praxis and war-peace issues firmly in the context of a suffering humanity and world. Both warn as to how fundamentalism may subjugate peace and security to a demagogic, uncompromising quest. These disciplines also nurture a community of speech that continues to find its voice even as others resort to war. The four books considered in this essay respond to the rush and risk of unnecessary conflict wrought by fundamentalists. -

A Guide to Contemporary Faith Wes Campbell, November 2011

1 A Guide to Contemporary Faith Wes Campbell, November 2011 Introduction Our time presents a crisis for Christian faith. In our situation which some describe as ‘post-Christian’ or post-Christendom, the challenge reaches into the heart of faith, challenging God in the name of ‘atheism’1. The crisis produces both pastoral and intellectual challenges, as the Christian community seeks to chart a way in our contemporary world. Often it is suggested that there are but two ways of responding, each offering an extreme position: either, a return to pre-modern (fundamentalist) ways of thinking, or, an unqualified (progressive) acceptance of modernist (or postmodernist) modes of thought. It sometimes seems as if we are being required to choose between two different fundamentalisms. However, as Christians grapple with these challenges, we are faced with an even more fundamental challenge: the challenge of God who speaks to our situation, bringing a crisis which challenges, judges and renews the world2. This paper is a brief response to our contemporary situation. Our main interest is to assist people to hear Jesus Christ’s call to discipleship in the 21st century. Here we will be reminded of the basic commitments made as the Uniting Church was formed. The discussion here will offer some pointers for the task of interpreting and understanding the Christian faith now3. Understanding Christian Faith From the beginning understanding biblical faith has been a controversial and challenging matter. The most obvious reason for this is that faith itself emerged from challenging and controversial circumstances. For example, the faith of Israel has its early origins in the escape of Hebrew slaves from Egypt, led by Moses. -

The Trinity for Unitarians 1

The Trinity for Unitarians - An Overview in 4 Parts by Rev. Tony Lorenzen pg. 1 The Trinity for Unitarians 1 – Overview and Method Method “You might say that Unitarianism has become dogmatic for us — the Trinity being something that a "good" UU simply cannot believe in because we are, by default, anti-Trinitarians. I'd suggest instead that UUs celebrate theological liberalism as a method rather than as a set of theological conclusions.” – Chris Walton, Editor UU World (in his blog “Philocrities”). “Christian Faith is the response to Jesus” not “getting back to the religion of Jesus.” The Trinity is part of that response as Jesus communities answer the question “How is God with us?” “When God is too close or too removed, humans take his place." Biblical Studies – historical critical method and the use of reason become the hallmark of anti-trinitarian theological method, yet many if not most of the Unitarian, Universalist and other “heretics” we encounter will use an “uncritical” approach to scripture in their justification for theological positions, even using “proof-texting” or citing scripture texts th uncritically to support their views, well into the 19 century. “Some of us UUs these days are just finding the Trinity a helpful metaphor and a window to God, however smudged.” – Rev. Tony Lorenzen Heresy/Hertics Heresy comes from a greek work meaning “to choose.” A heretic is someone who has not given up the right to choose what to think or what to believe. Heresy is measured in juxtaposition to orthodoxy or “right” thinking. Arianism - from Arius (256-336) north African priest (leader). -

Hymns Ancient and Modern Booksonix Records

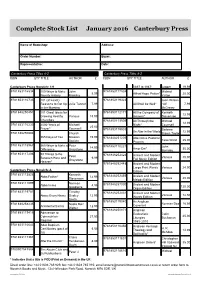

Complete Stock List January 2016 Canterbury Press Name of Bookshop: Address: Order Number: Buyer: Representative: Date: Canterbury Press Titles A-Z Canterbury Press Titles A-Z ISBN QTY TITLE AUTHOR £ ISBN QTY TITLE AUTHOR £ Canterbury Press Norwich: 1-9 1897 to 1987* Jagger 19.99 9781853116834 100 Ways to Make John 9781853117534 Michael 5.99 Alfred Hope Patten* 20.00 Poverty History Madeley Yelton 9781853116735 101 (at Least) 9781853119323 Joan Wilson Reasons to Get Up Julie Tanner 7.99 All Shall be Well* / Alf 7.99 in the Morning McCreary 9781848250451 101 Great Ideas for 9781853112171 All the Company of Kenneth 12.99 Growing Healthy Various 18.99 Heaven* Stevenson Churches 9781853113505 All Through the MIchael 12.99 9781853116230 2000 Years of Michael Night* Counsell 25.00 Prayer* Counsell 9781853119903 Barbara An Altar in the World 12.99 9781848250604 Church Brown Taylor 365 Days of Yes Mission 19.99 9781848251205 Alternative Pastoral Tess Ward 25.00 Society Prayers 9781853115967 365 Ways to Make a Peter 9781853110221 John 14.99 Amor Dei* 30.00 Difference Graystone Burnaby 9781853117206 99 Things to Do Peter 9781848252424 Ancient and Modern Between Here and 9.99 Various 30.00 Graystone Full Music Edition Heaven* 9781848252448 Ancient and Modern Large Print Words Various 24.00 Canterbury Press Norwich: A Edition 9781853113826 Kenneth 9781848252455 Ancient and Modern Abba Father* 12.99 Various 20.00 Stevenson Melody Edition 9781853111099 Norman 9781848257030 Ancient and Modern Abba Imma 4.95 120.00 Goodacre Organ Edition 9781853119781 Timothy 9781848252431 Ancient and Modern Various 12.50 Above Every Name Dudley 12.99 Words Edition Smith 9781853119040 An Anglican 9781848258235 Nadia Bolz Norman Doe 16.99 Accidental Saints 12.99 Covenant Weber 9781848250871 Anglican 9781853119415 Admission to Eucharistic Colin 45.00 Communion 27.50 Liturgies Buchanan Register 1985-2010 9781853116643 Adult Baptism 9781853110450 Anglican Heritage: H. -

The Personal Politics of Spirituality: on the Lived Relationship Between Contemporary Spirituality and Social Justice Among Canadian Millennials

THE PERSONAL POLITICS OF SPIRITUALITY: ON THE LIVED RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CONTEMPORARY SPIRITUALITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE AMONG CANADIAN MILLENNIALS by Galen Watts A thesis submitted to the Cultural Studies Graduate Program In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada April, 2016 Copyright © Galen Watts, 2016 ii Abstract In the last quarter century, a steadily increasing number of North Americans, when asked their religious affiliation, have self-identified as “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR). Resultantly, a wealth of literature on the subject of contemporary spirituality has recently emerged. Some suggest, generally, that we are seeing the emergence of a “progressive spirituality” that is potentially transformative and socially conscious. Conversely, there are scholars who have taken a more critical stance toward this recent cultural development, positing that contemporary spirituality is a byproduct of the self-obsessed culture which saturates the west, or that spirituality, at its worst, is simply a rebranding of religion in order to support consumer culture and the ideology of capitalism. One problem with the majority of this literature is that scholars have tended to offer essentialist or reductionist accounts of spirituality, which rely primarily on a combination of theoretical and textual analysis, ignoring both the lived aspect of spirituality in contemporary society and its variation across generations. This thesis is an attempt to mitigate some of this controversy whilst contributing to this burgeoning scholarly field. I do so by shedding light on contemporary spirituality, as it exists in its lived form. Espousing a lived religion framework, and using the qualitative data I collected from conducting semi-structured interviews with twenty Canadian millennials who consider themselves “spiritual but not religious,” I assess the cogency of the dominant etic accounts of contemporary spirituality in the academic literature. -

A Sociology of Progressive Religious Groups Why Liberal Religious Groups Cannot Get Together

A Sociology of Progressive Religious Groups Why Liberal Religious Groups Cannot Get Together A Talk for Sea of Faith Yorkshire, 22 September 2007, Bradford Given by Adrian Worsfold Schisms are normally carried out by traditionalists or conversionists over what is called a "presenting issue". This is not the question here but the inability of liberal groups to get together. Indeed liberals tend not to split off as groups, but they do move out as individuals. When Theophilus Lindsey rejected the 39 Articles of the Church of England and set up the first named Unitarian Church in 1774, he hoped for an exodus of Anglicans to join his new Arian based movement (he followed Samuel Clarke's Arian revision of the Book of Common Prayer). An exodus did not happen. The Arians stayed within the Church of England, and Essex Church as it was called became absorbed into the liberalising Presbyterian movement. Did not these Presbyterians split then, long before? Well, when the Presbyterians broke away from the Church of England they were fiercely Puritan and very trinitarian, with full confidence in the Bible alone to uphold Calvinist doctrine. So this too was an example of an evangelical breakaway. That they became liberal was an unintended consequence of the original Puritan intention, and they were later boosted by ideological liberals (who were also biblical literalists, reading a unitarian doctrine straight off the gospels as, indeed, the New Testament contains no doctrine of the Trinity, only its possibility). So what is this about liberal groups and then not being able to be inclusive of one another? We first need to know what groups we are talking about, what they organise for and how they function. -

Cathedral of Hope: a History of Progressive Christianity, Civil

CATHEDRAL OF HOPE: A HISTORY OF PROGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND GAY SOCIAL ACTIVISM IN DALLAS, TEXAS, 1965 -1992 Dennis Michael Mims, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2009 APPROVED: J. Todd Moye, Major Professor Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Committee Member Marilyn Morris, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Mims, Dennis Michael. Cathedral of Hope: A History of Progressive Christianity, Civil Rights, and Gay Social Activism in Dallas, Texas, 1965 - 1992. Master of Science (History), August 2009, 120 pp., 6 photos, references, 48 titles. This abstract is for the thesis on the Cathedral of Hope (CoH). The CoH is currently the largest church in the world with a predominantly gay and lesbian congregation. This work tells the history of the church which is located in Dallas, Texas. The thesis employs over 48 sources to help tell the church’s rich history which includes a progressive Christian philosophy, an important contribution to the fight for gay civil rights, and fine examples of courage through social activism. This work makes a contribution to gay history as well as civil rights history. It also adds to the cultural and social history which concentrates on the South and Southwestern regions of the United States. Copyright 2009 by Dennis Michael Mims ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. AN INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 II. GAY LIBERATION AND THE BIRTH OF A CHURCH .................. 14 III. MCC DALLAS: THE NEW CHURCH BECOMES AN ANCHOR TO THE GAY COMMUNITY.................................. -

Rev. Dr. Robert E. Shore-Goss

A division of WIPF and STOCK Publishers CASCADE Books wipfandstock.com • (541) 344-1528 GOD IS GREEN An Eco-Spirituality of Incarnate Compassion Robert E. Shore-Goss At this time of climate crisis, here is a practical Christian ecospirituality. It emerges from the pastoral and theological experience of Rev. Robert Shore-Goss, who worked with his congregation by making the earth a member of the church, by greening worship, and by helping the church building and operations attain a carbon neutral footprint. Shore-Goss explores an ecospirituality grounded in incarnational compassion. Practicing incarnational compassion means following the lived praxis of Jesus and the commission of the risen Christ as Gardener. Jesus becomes the “green face of God.” Restrictive Christian spiritualities that exclude the earth as an original blessing of God must expand. is expansion leads to the realization that the incarnation of Christ has deep roots in the earth and the fleshly or biological tissue of life. is book aims to foster ecological conversation in churches and outlines the following practices for congregations: meditating on nature, inviting sermons on green topics, covenanting with the earth, and retrieving the natural elements of the sacraments. ese practices help us recover ourselves as fleshly members of the earth and the network of life. If we fall in love with God’s creation, says Shore-Goss, we will fight against climate change. Robert E. Shore-Goss has been Senior Pastor and eologian of MCC United Church of Christ in the Valley (North Hollywood, California) since June 2004. He has made his church a green church with a carbon neutral footprint. -

Sacred Union Ceremonies: How Gnostics Mimic Marriage

Sacred Union Ceremonies: How Gnostics mimic marriage The Sacred Union Ceremony On 12 June 2010 a sacred union ceremony, organised by Uniting Network Australia, was held at Brunswick Uniting Church in Melbourne to bless same-sex couples in committed relationships. Robed clergy officiated, a sermon was preached, vows were exchanged, certificates signed and a wedding cake provided. The following day President Alistair Macrae received a copy of the liturgy used in the ceremony and advised UNA leaders that ‘if they want clarity in this matter they should consider the usual church processes for introducing it through the Councils of the Church for discussion, discernment and debate.’ 1 In the light of decisions at the 2003 and 2006 Assemblies that implicitly accepted same-sex relations among ordained ministers as a legitimate form of diversity in the UCA, it is not surprising that formal recognition of same-sex relationships is now sought. UNA is highly likely to bring a recommendation on this matter to the Thirteenth Assembly, 15-21 July 2012. As the UCA has never given theological reasons for these seismic changes to the Reformed doctrine of sexuality and marriage, it is necessary to try to understand why something so recently regarded as inimical to human flourishing is now strongly supported and promoted as a positive good and an inalienable right. From Christian Orthodoxy to Gnostic Spirituality The answer is to be found in the shift from Christian patterns of thought to those based on new forms of Gnostic spirituality – an abstract, other worldly philosophy that was parasitic on orthodox Christian belief and focussed on esoteric knowledge (gnosis ) of the spiritual world that is accessible to people when they look deep within themselves.2 Until recently considered to be a relic of a bygone age, and an escape from a robust secular faith, the resurgence of Gnostic spirituality within and beyond the churches is remarkable. -

Can Art Be Used to Both Celebrate Indian Culture and Keep It Alive?

Can art be used to both celebrate Indian culture and keep it alive? Rianne Karra ID: S17104342 Birmingham City University BA Art and Design 13/01/20 1 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………….3 Chapter 1………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter 2………………………………………………………………………5 Chapter 3.……………………………………………………………………..6 Chapter 4……………………………………………………………………….7-12 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………..13 Bibliography………………………………………………………………….14-17 Appendix………………………………………………………………………..18 2 Introduction This dissertation looks into the importance of both celebrating and keeping Indian culture alive in the UK today and how art can be used to do that. Celebrating the diversity and difference within the UK, that came as a part of immigration. Chapter one, addresses how the current situation of Britain, has left us to believe if Britain is as diverse as we imagine it to be, with issues like Brexit allowing for hate crimes and discrimination. Chapter two, reflects how Britain has become home to minority communities through post war immigration and highlights the issues of low minority participation in the arts but how art can be used to sustain Indian culture. By doing so, might prevent assimilation from occurring which chapter three looks into. By looking at the work of two British Asian artists through case studies: Chila Kumari Burman and Navi Kaur, who use their practice to display culture through community and celebrate difference. As a person of British Asian heritage, the idea of identity can be difficult to define, as it is made up of multiple aspects, and two very different components, Britishness and our ancestral culture. Our culture has been carried between generations, and continued on within Britain by us and the beliefs we uphold. -

Churchof England

THE TaTakinkingtgthehe CHURCHOF GospeGospelonlon ENGLAND tourtour Newspaper p9p9 25.05.18 £1.50 No: 6434 Established in 1828 AVAILABLE ON GooglePlay iTunes DIGEST Churches unitetoremember Youth Trust boost AYoung Leaders Award scheme runbythe Archbishop of York is to be expanded fatefulManchesterbombing nationally. CHURCHES in Manchester St Ann’s Squarewas the focal The Allchurches Trust this wereatthe centreofevents point for people’s grief when an week awarded agrant of over this weekmarking the first estimated 300,000 floral tributes £500,000 to the Archbishop of anniversaryofthe bombing and gifts wereleft in the Square. York Youth Trust to enable the in Manchester Arena. This year the flower festival expansion. The Bishop of Manchester, featured displays created by 23 Dr John Sentamu founded the theRtRev David Walker,said: groups of flower arrangers from Trust in 2009 with the aim of “At the heartofour commemo- around the country empowering anew generation rations will be those families Each of the 25 floral displays of young leaders. So far over mostaffectedbythe attack. We depicted an aspect of Manches- 63,000 young people across the will gatherwith them, first in ter.They included titles such as North of England have benefit- the cathedral and later outside ‘A City United’ sponsored by ted from the scheme. the Town Halland in St Ann’s Manchester City and Manches- Square. We will let them know ter United Football Clubs, ‘Suf- Kirkbacks same-sex theyare not forgotten, andthat fragette City’, a‘City of Prayer ourcommitment to them, and Contemplation’ and ‘Coro- marriage through word, prayer and nation Street’, complete with action, is not diminished by a pigeon and Minnie Caldwell’s year’s passing.” Bobby the cat.