Lectures in Contemporary Anglicanism Credo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Group on Human Sexuality

IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page i The House of Bishops Working Group on human sexuality Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page ii Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page iii Report of the House of Bishops Working Group on human sexuality November 2013 Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page iv Church House Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this Church House publication may be reproduced or Great Smith Street stored or transmitted by any means London or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, SW1P 3AZ recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought ISBN 978 0 7151 4437 4 (Paperback) from [email protected] 978 0 7151 4438 1 (CoreSource EBook) 978 0 7151 4439 8 (Kindle EBook) Unless otherwise indicated, the Scripture quotations contained GS 1929 herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright Published 2013 for the House © 1989, by the Division of Christian of Bishops of the General Synod Education of the National Council of the Church of England by Church of the Churches of Christ in the -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 14 September 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Higton, Mike (2018) 'Rowan Williams.', in The Oxford handbook of ecclesiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 505-523. Oxford handbooks. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199645831.013.15 Publisher's copyright statement: Higton, Mike (2018). Rowan Williams. In The Oxford Handbook of Ecclesiology. Avis, Paul Oxford: Oxford University Press. 505-523, reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199645831.013.15 Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk ROWAN WILLIAMS MIKE HIGTON ABSTRACT Rowan Williams' ecclesiology is shaped by his account of the spiritual life. He examines the transformation of human beings' relationships to one another driven by their encounter with God's utterly gracious love in Jesus Christ. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

{FREE} Living Holiness Ebook

LIVING HOLINESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Helen Roseveare | 224 pages | 20 Jul 2008 | Christian Focus Publications Ltd | 9781845503529 | English | Tain, United Kingdom Christian Living: Holiness In a series of messages given at Moody Bible Institute in , Andrew Murray explained how to live a Spirit-filled life. This book, coming from those messages, is wise and timely counsel from a veteran saint and journeyman in the life of faith. In an era when discussion of the deeper life is The Way to Pentecost by Samuel Chadwick. If you enjoy the writings of Leonard Ravenhill and A. Tozer, you will love this little volume on the Holy Spirit by Samuel Chadwick. This book was written with the purpose of helping readers understand what holiness is, why we should be holy, how to remain holy, etc. Holiness and Power by A. This book grew out of a burning desire in the author's soul to tell to others what he himself so longed to know a quarter of a century ago. When the truth dawned upon him in all its preciousness, it seemed to him that he could point out the way to receive the desired blessing of the Holy The Land and Life of Rest by W. Graham Scroggie. This little book of Keswick Bible Readings is the best treatment of the Book of Joshua that we have found. The New Testament teaching of "life more abundant" is ably expounded from this Old Testament book by one who had evidently entered into an experiential knowledge of those things The Purity Principle by Randy Alcorn. -

Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Turbulent Priests? The Archbishop of Canterbury in contemporary English politics Daniel Gover Theos Friends’ Programme Theos is a public theology think tank which seeks to influence public opinion about the role of faith and belief in society. We were launched in November 2006 with the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. We provide • high-quality research, reports and publications; • an events programme; • news, information and analysis to media companies and other opinion formers. We can only do this with your help! Theos Friends receive complimentary copies of all Theos publications, invitations to selected events and monthly email bulletins. If you would like to become a Friend, please detach or photocopy the form below, and send it with a cheque to Theos for £60. Thank you. Yes, I would like to help change public opinion! I enclose a cheque for £60 made payable to Theos. Name Address Postcode Email Tel Data Protection Theos will use your personal data to inform you of its activities. If you prefer not to receive this information please tick here By completing you are consenting to receiving communications by telephone and email. Theos will not pass on your details to any third party. Please return this form to: Theos | 77 Great Peter Street | London | SW1P 2EZ S: 97711: D: 36701: Turbulent Priests? what Theos is Theos is a public theology think tank which exists to undertake research and provide commentary on social and political arrangements. We aim to impact opinion around issues of faith and belief in The Archbishop of Canterbury society. -

Canon Treasurer

Canon Treasurer 1 PROFILE OF CANTERBURY CATHEDRAL St Augustine, the first Archbishop of Canterbury, arrived on the coast of Kent as a missionary to England in 597 AD. He came from Rome, sent by Pope Gregory the Great. It is said that Gregory had been struck by the beauty of Angle slaves he saw for sale in the city market and dispatched Augustine and some monks to convert them to Christianity. Augustine was given a church at Canterbury (St Martin’s, after St Martin of Tours, still standing today) by the local King, Ethelbert whose Queen, Bertha, a French Princess, was already a Christian. This building had been a place of worship during the Roman occupation of Britain and is the oldest church in England still in use. Augustine had been consecrated a bishop in France and was later made an archbishop by the Pope. He established his seat within the Roman city walls (the word cathedral is derived from the Latin word for a chair ‘cathedra’, which is itself taken from the Greek ‘kathedra’ meaning seat.) and built the first Cathedral there, becoming the first Archbishop of Canterbury. Since that time, there has been a community around the Cathedral offering daily prayer to God; this community is arguably the oldest organisation in the English speaking world. The present Archbishop, The Most Revd Justin Welby, is 105th in the line of succession from Augustine. Augustine’s original building lies beneath the floor of the nave– it was extensively rebuilt and enlarged by the Saxons, and the Cathedral was rebuilt completely by the Normans in 1070 following a major fire. -

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania Prepared for the US Department of Defense’s Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance May 2020 Written by: Jonah Bhide Grace Frazor Charlotte Gorman Claire Huitt Christopher Zimmer Under the supervision of Dr. Joshua Busby 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 United States 8 Oceania 22 China 30 Australia 41 New Zealand 48 France 53 Japan 61 Policy Recommendations for US Government 66 3 Executive Summary Research Question The current strategic landscape in Oceania comprises a variety of complex and cross-cutting themes. The most salient of which is climate change and its impact on multilateral political networks, the security and resilience of governments, sustainable development, and geopolitical competition. These challenges pose both opportunities and threats to each regionally-invested government, including the United States — a power present in the region since the Second World War. This report sets out to answer the following questions: what are the current state of international affairs, complexities, risks, and potential opportunities regarding climate security issues and geostrategic competition in Oceania? And, what policy recommendations and approaches should the US government explore to improve its regional standing and secure its national interests? The report serves as a primer to explain and analyze the region’s state of affairs, and to discuss possible ways forward for the US government. Given that we conducted research from August 2019 through May 2020, the global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus added additional challenges like cancelling fieldwork travel. However, the pandemic has factored into some of the analysis in this report to offer a first look at what new opportunities and perils the United States will face in this space. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Toward a Constitutionalism of the Global South

1 1 CN Introduction CT Toward a Constitutionalism of the Global South Daniel Bonilla The grammar of modern constitutionalism determines the structure and limits of key components of contemporary legal and political discourse. This grammar constitutes an important part of our legal and political imagination. It determines what questions we ask about our polities, as well as the range of possible answers to these questions. This grammar consists of a series of rules and principles about the appropriate use of concepts like people, self-government, citizen, rights, equality, autonomy, nation, and popular sovereignty.1 Queries about the normative relationship among state, nation, and cultural diversity; the criteria that should be used to determine the legitimacy of the state; the individuals who can be considered members of the polity; the distinctions and limits between the private and public spheres; and the differences between autonomous and heteronomous political communities makes sense to us because they emerge from the rules and principles of modern constitutionalism. Responses to these questions are certainly diverse. Different traditions of interpretation in modern constitutionalism – liberalism, communitarianism, and nationalism, among others – compete to control the way these concepts are understood and put into practice.2 Yet these questions and answers cannot violate the conceptual borders established by modern constitutionalism. If they do, they would be considered unintelligible, irrelevant, or useless. Today, for example, it would be difficult to accept the relevancy of a question about the relationship between the 2 2 legitimacy of the state and the divine character of the king. It would also be very difficult to consider valuable the idea that the fundamental rights of citizens should be a function of race or gender. -

ND Sept 2019.Pdf

usually last Sunday, 5pm. Mass Tuesday, Friday & Saturday, 9.30am. Canon David Burrows SSC , 01422 373184, rectorofel - [email protected] parish directory www.ellandoccasionals.blogspot.co.uk FOLKESTONE Kent , St Peter on the East Cliff A Society BATH Bathwick Parishes , St.Mary’s (bottom of Bathwick Hill), Wednesday 9.30am, Holy Hour, 10am Mass Friday 9.30am, Sat - Parish under the episcopal care of the Bishop of Richborough . St.John's (opposite the fire station) Sunday - 9.00am Sung Mass at urday 9.30am Mass & Rosary. Fr.Richard Norman 0208 295 6411. Sunday: 8am Low Mass, 10.30am Solemn Mass. Evensong 6pm. St.John's, 10.30am at St.Mary's 6.00pm Evening Service - 1st, Parish website: www.stgeorgebickley.co.uk Weekdays - Low Mass: Tues 7pm, Thur 12 noon. 3rd &5th Sunday at St.Mary's and 2nd & 4th at St.John's. Con - http://stpetersfolk.church e-mail :[email protected] tact Fr.Peter Edwards 01225 460052 or www.bathwick - BURGH-LE-MARSH Ss Peter & Paul , (near Skegness) PE24 parishes.org.uk 5DY A resolution parish in the care of the Bishop of Richborough . GRIMSBY St Augustine , Legsby Avenue Lovely Grade II Sunday Services: 9.30am Sung Mass (& Junior Church in term Church by Sir Charles Nicholson. A Forward in Faith Parish under BEXHILL on SEA St Augustine’s , Cooden Drive, TN39 3AZ time) On 5th Sunday a Group Mass takes place in one of the 6 Bishop of Richborough . Sunday: Parish Mass 9.30am, Solemn Saturday: Mass at 6pm (first Mass of Sunday)Sunday: Mass at churches in the Benefice. -

Adroddiad Blynyddol 1979

ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL / ANNUAL REPORT 1978-79 J D K LLOYD 1979001 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Mr J D K Lloyd, O.B.E., D.L., M.A., LL.D., F.S.A., Garthmyl, Powys. Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1978-79 Disgrifiad / Description Two deed boxes containing papers of the late Dr. J. D. K. Lloyd (1900-78), antiquary, author of A Guide to Montgomery and of various articles on local history, formerly mayor of Montgomery and high sheriff of Montgomeryshire, and holder of several public and academic offices [see Who's Who 1978 for details]. The one box, labelled `Materials for a History of Montgomery', contains manuscript volumes comprising a copy of the glossary of the obsolete words and difficult passages contained in the charters and laws of Montgomery Borough by William Illingworth, n.d. [watermark 1820), a volume of oaths of office required to be taken by officials of Montgomery Borough, n.d., [watermark 1823], an account book of the trustees of the poor of Montgomery in respect of land called the Poors Land, 1873-96 (with map), and two volumes of notes, one containing notes on the bailiffs of Montgomery for Dr. Lloyd's article in The Montgomeryshire Collections, Vol. 44, 1936, and the other containing items of Montgomery interest extracted from Archaeologia Cambrensis and The Montgomeryshire Collections; printed material including An Authentic Statement of a Transaction alluded to by James Bland Burgess, Esq., in his late Address to the Country Gentlemen of England and Wales, 1791, relating to the regulation of the practice of county courts, Letters to John Probert, Esq., one of the devisees of the late Earl of Powis upon the Advantages and Defects of the Montgomery and Pool House of Industry, 1801, A State of Facts as pledged by Mr. -

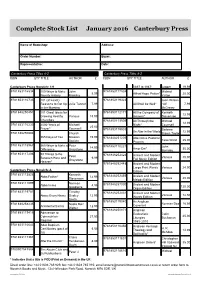

Hymns Ancient and Modern Booksonix Records

Complete Stock List January 2016 Canterbury Press Name of Bookshop: Address: Order Number: Buyer: Representative: Date: Canterbury Press Titles A-Z Canterbury Press Titles A-Z ISBN QTY TITLE AUTHOR £ ISBN QTY TITLE AUTHOR £ Canterbury Press Norwich: 1-9 1897 to 1987* Jagger 19.99 9781853116834 100 Ways to Make John 9781853117534 Michael 5.99 Alfred Hope Patten* 20.00 Poverty History Madeley Yelton 9781853116735 101 (at Least) 9781853119323 Joan Wilson Reasons to Get Up Julie Tanner 7.99 All Shall be Well* / Alf 7.99 in the Morning McCreary 9781848250451 101 Great Ideas for 9781853112171 All the Company of Kenneth 12.99 Growing Healthy Various 18.99 Heaven* Stevenson Churches 9781853113505 All Through the MIchael 12.99 9781853116230 2000 Years of Michael Night* Counsell 25.00 Prayer* Counsell 9781853119903 Barbara An Altar in the World 12.99 9781848250604 Church Brown Taylor 365 Days of Yes Mission 19.99 9781848251205 Alternative Pastoral Tess Ward 25.00 Society Prayers 9781853115967 365 Ways to Make a Peter 9781853110221 John 14.99 Amor Dei* 30.00 Difference Graystone Burnaby 9781853117206 99 Things to Do Peter 9781848252424 Ancient and Modern Between Here and 9.99 Various 30.00 Graystone Full Music Edition Heaven* 9781848252448 Ancient and Modern Large Print Words Various 24.00 Canterbury Press Norwich: A Edition 9781853113826 Kenneth 9781848252455 Ancient and Modern Abba Father* 12.99 Various 20.00 Stevenson Melody Edition 9781853111099 Norman 9781848257030 Ancient and Modern Abba Imma 4.95 120.00 Goodacre Organ Edition 9781853119781 Timothy 9781848252431 Ancient and Modern Various 12.50 Above Every Name Dudley 12.99 Words Edition Smith 9781853119040 An Anglican 9781848258235 Nadia Bolz Norman Doe 16.99 Accidental Saints 12.99 Covenant Weber 9781848250871 Anglican 9781853119415 Admission to Eucharistic Colin 45.00 Communion 27.50 Liturgies Buchanan Register 1985-2010 9781853116643 Adult Baptism 9781853110450 Anglican Heritage: H.