Stephen P. Marks the United Nations and Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 The first UN Infantry Battalion was deployed as part of United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF-I). UN infantry soldiers march in to Port Said, Egypt, in December 1956 to assume operational responsibility. asdf ‘The United Nations Infantry Battalion is the backbone of United Nations peacekeeping, braving danger, helping suffering civilians and restoring stability across war-torn societies. We salute your powerful contribution and wish you great success in your life-saving work.’ BAN Ki-moon United Nations Secretary-General United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual ii Preface I am very pleased to introduce the United Nations Infantry Battalion Man- ual, a practical guide for commanders and their staff in peacekeeping oper- ations, as well as for the Member States, the United Nations Headquarters military and other planners. The ever-changing nature of peacekeeping operations with their diverse and complex challenges and threats demand the development of credible response mechanisms. In this context, the military components that are deployed in peacekeeping operations play a pivotal role in maintaining safety, security and stability in the mission area and contribute meaningfully to the achievement of each mission mandate. The Infantry Battalion con- stitutes the backbone of any peacekeeping -

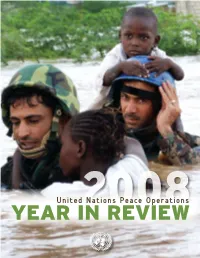

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Reputation As a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected]

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2019 Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2035 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, Organizations Law Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Daugirdas, Kristina. "Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations." Am. J. Int'l L. 113, no. 2 (2019): 221-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2019 by The American Society of International Law doi:10.1017/ajil.2018.122 REPUTATION AS A DISCIPLINARIAN OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS By Kristina Daugirdas* ABSTRACT As a disciplinarian of international organizations, reputation has serious shortcomings. Even though international organizations have strong incentives to maintain a good reputation, reputational concerns will sometimes fail to spur preventive or corrective action. Organizations have multiple audiences, so efforts to preserve a “good” reputation may pull organizations in many different directions, and steps taken to preserve a good reputation will not always be salutary. Recent incidents of sexual violence by UN peacekeepers in the Central African Republic illustrate these points. On April 29, 2015, The Guardian published an explosive story based on a leaked UN document.1 The document described allegations against French troops who had been deployed to the Central African Republic pursuant to a mandate established by the Security Council. -

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook UNITED NATIONS FORCE HEADQUARTERS HANDBOOK November 2014 United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook Foreword The United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook aims at providing information that will contribute to the understanding of the functioning of the Force HQ in a United Nations field mission to include organization, management and working of Military Component activities in the field. The information contained in this Handbook will be of particular interest to the Head of Military Component I Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander and Force Chief of Staff. The information, however, would also be of value to all military staff in the Force Headquarters as well as providing greater awareness to the Mission Leadership Team on the organization, role and responsibilities of a Force Headquarters. Furthermore, it will facilitate systematic military planning and appropriate selection of the commanders and staff by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Since the launching of the first United Nations peacekeeping operations, we have collectively and systematically gained peacekeeping expertise through lessons learnt and best practices of our peacekeepers. It is important that these experiences are harnessed for the benefit of current and future generation of peacekeepers in providing appropriate and clear guidance for effective conduct of peacekeeping operations. Peacekeeping operations have evolved to adapt and adjust to hostile environments, emergence of asymmetric threats and complex operational challenges that require a concerted multidimensional approach and credible response mechanisms to keep the peace process on track. The Military Component, as a main stay of a United Nations peacekeeping mission plays a vital and pivotal role in protecting, preserving and facilitating a safe, secure and stable environment for all other components and stakeholders to function effectively. -

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook UNITED NATIONS FORCE HEADQUARTERS HANDBOOK November 2014 United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook Foreword The United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook aims at providing information that will contribute to the understanding of the functioning of the Force HQ in a United Nations field mission to include organization, management and working of Military Component activities in the field. The information contained in this Handbook will be of particular interest to the Head of Military Component I Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander and Force Chief of Staff. The information, however, would also be of value to all military staff in the Force Headquarters as well as providing greater awareness to the Mission Leadership Team on the organization, role and responsibilities of a Force Headquarters. Furthermore, it will facilitate systematic military planning and appropriate selection of the commanders and staff by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Since the launching of the first United Nations peacekeeping operations, we have collectively and systematically gained peacekeeping expertise through lessons learnt and best practices of our peacekeepers. It is important that these experiences are harnessed for the benefit of current and future generation of peacekeepers in providing appropriate and clear guidance for effective conduct of peacekeeping operations. Peacekeeping operations have evolved to adapt and adjust to hostile environments, emergence of asymmetric threats and complex operational challenges that require a concerted multidimensional approach and credible response mechanisms to keep the peace process on track. The Military Component, as a main stay of a United Nations peacekeeping mission plays a vital and pivotal role in protecting, preserving and facilitating a safe, secure and stable environment for all other components and stakeholders to function effectively. -

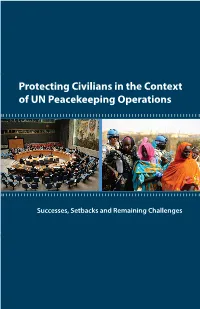

Protecting Civilians in the Context of UN Peacekeeping Operations

About this publication Since 1999, an increasing number of United Nations peacekeeping missions have been expressly mandated to protect civilians. However, they continue to struggle to turn that ambition into reality on the ground. This independent study examines the drafting, interpretation, and implementation of such mandates over the last 10 years and takes stock of the successes and setbacks faced in this endeavor. It contains insights and recommendations for the entire range of United Nations protection actors, including the Security Council, troop and police contributing countries, the Secretariat, and the peacekeeping operations implementing protection of civilians mandates. Protecting Civilians in the Context Protecting Civilians in the Context the Context in Civilians Protecting This independent study was jointly commissioned by the Department of Peace keeping Opera- Operations Peacekeeping UN of tions and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs of the United Nations. of UN Peacekeeping Operations Front cover images (left to right): Spine images (top to bottom): The UN Security Council considers the issue of the pro A member of the Indian battalion of MONUC on patrol, 2008. Successes, Setbacks and Remaining Challenges tection of civilians in armed conflict, 2009. © UN Photo/Marie Frechon. © UN Photo/Devra Berkowitz). Members of the Argentine battalion of the United Nations Two Indonesian members of the African Union–United Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) assist an elderly Nations Hybrid operation in Darfur (UNAMID) patrol as woman, 2008. © UN Photo/Logan Abassi. women queue to receive medical treatment, 2009. © UN Photo/Olivier Chassot. Back cover images (left to right): Language: ENGLISH A woman and a child in Haiti receive emergency rations Sales #: E.10.III.M.1 from the UN World Food Programme, 2008. -

United Nations Development Action Framework 2013-17

INDIA UNDAF United Nations Development Action Framework 2013-2017 Cover Photo Credit: UNICEF and UNHCR Copyright: United Nations Resident Coordinator’s Office Formulated in 2011, printed in June 2012 INDIA UNDAF United Nations Development Action Framework 2013-2017 India UNDAF UnitedIndia UNDAF Nations UnitedDevelopment Nations Action Development Framework Action 2013-2017 Framework 2013-2017 2 Photo Credit: UNICEF India UNDAF United Nations Development Action Framework 2013-2017 Contents Foreword 4 India UNDAF 2013-2017 6 Executive Summary 7 1. Context 12 1.1 The UNDAF Formulation Process 12 1.2 Country Assessment 13 1.3 Lessons Learned from UNDAF 2008-12 18 1.4 The Comparative Advantage of the UN in India 19 1.5 The Vision and Mission of the UNDAF 20 1.6 Context and Focus of the UNDAF 21 2. The UNDAF Outcomes 22 2.1 Outcome 1: Inclusive Growth 22 2.2 Outcome 2: Food and Nutrition Security 30 2.3 Outcome 3: Gender Equality 34 2.4 Outcome 4: Equitable Access to Quality Basic Services [Health; Education; HIV and AIDS; Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH)] 40 2.5 Outcome 5: Governance 50 2.6 Outcome 6: Sustainable Development 54 3. Programme Implementation and Operations Management 60 3.1 Geographical Focus 60 3.2 Partnerships 61 3.3 Programme Management 61 3.4 Monitoring 63 3.5 Evaluation 64 3.6 Operations Management 64 4. Resource Requirements 66 Annexures Annexure 1: International Covenants/Conventions/Treaties Ratified/Acceded/Signed by India 68 Annexure 2: Terms of Reference for Programme Management Team (PMT) 70 Annexure 3: Terms of -

Libya and the Danish Way Of

106 Good News: Libya and the Danish Way of War Peter Viggo Jakobsen and Karsten Jakob Møller1 DANISH FOREIGN POLICY YEARBOOK 2012 FOREIGN POLICY DANISH ‘I have good news’ – this is how a smiling Danish Minister of Foreign Af- fairs Espersen announced the decision to send F-16 fighter jets to Libya to the media.2 No one batted an eyelid. The notion that it was good news that Denmark was going to war was almost universally shared. All parties in parliament, all major news outlets and 78% of the population applauded the decision. This level of public support was the highest polled among the nations participating in the initial phase of the air campaign.3 This appetite for war should come as no surprise. It had already been evi- dent during the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO) air war over Kosovo in 1999 when the Danes also topped the polls conducted among NATO member states, and news late in the campaign that Danish F-16s had dropped bombs on Serbian targets was greeted with pride and joy.4 It is also visible in the fact that Danes remain the top supporters of NATO’s mission in Afghanistan, even though Denmark, with 42 soldiers killed, has suffered the highest number of casualties per capita.5 This was further underlined in early 2012 when Danes were the strongest supporters of launching a ground invasion in order to stop the Iranian nuclear program.6 This demonstrates Denmark’s remarkable journey from Venus to Mars, as Kagan would have put it.7 From the defeat to Prussia in 1864 till the end of the Cold War, Denmark resided on Venus with a defence and security policy that was characterized by a peacekeeping and mediation approach. -

On the Frontline: Youth, Peace and Security

Youth, Peace On the Frontline: and Security Report 14 This report is written by Kjersti Kanestrøm Lie Editor: Ingvill Breivik Design and illustration: Kristoffer Nilsen [saftogvann.com] Translation: Camilla Lorentzen The report is funded by Norad (the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation) 2 Youth is the most important weapon for peace In December 2015, the Security Council of an overarching principle. The fact that the the United Nations (UN) passed the resolu- Security Council passed this resolution is a tion 2250 on Youth, Peace and Security. This victory for young peace activists worldwide. is the first ever resolution by the UN on peace It gives clear measures to decision makers on keeping and security policy where young peo- how youth should be included in peace and ple are placed at the centre. It challenges the security work. Now the politicians need to way we think about youth in conflict, from follow up the work. being a problem, to being the main solution More than one year has passed since the in creating a more peaceful world. resolution was approved, and implementa- “The greatest strength is that it [the tion efforts have slowly started, but not as resolution] comes from young people fast as they should.With this report, LNU themselves” says Libyan Hajer Sharief in an wishes to put the resolution further up on the interview in this report. In 2017 Sharief won agenda in Norway and contribute to 2250 the Student Peace Prize, and has been one of being followed up by decision makers natio- the young people central to the efforts that nally, regionally and internationally. -

Meld. St. 33 (2011–2012) Report to the Storting (White Paper)

Meld. St. 33 (2011–2012) Report to the Storting (white paper) Published by: Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Norway and the United Nations: Common Future, Internet address: www.government.no Common Solutions Cover design: Anna Maria Pirolt/Felix Media Printed by: 07 Aurskog AS 03/2013 ER JØM KE IL T M 2 4 9 1 7 3 Trykksak Cover photo: Row 1: 1. Giacomo Pirozzi/ UNICEF, 2. Guri Dahl/ tinagent.com, 3. Victoria Hazou/ UN Photo, 4. Albert Gonzales Farran/ UN Photo, 5. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Row 3: 1. Johan Wildhagen/ Innovation Norway, 2. John Isaac/ UN Photo Row 4: 1. Bernadino Soares/ UN Poto, 2. Eskinder Debebe/ UN Photo Row 5: 1. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Row 6: 1. Jacob Silberberg/Panos Pictures /Felix Features, 2. UN Photo/Joao Araujo Row 7: 1. Sigrun Agøy Engum/ Norway UN, 2. Marco Dormino/ UN Photo Meld. St. 33 (2011–2012) Report to the Storting (white paper) Norway and the United Nations: Common Future, Common Solutions Contents Summary ......................................................... 5 3 The international legal order, human rights and gender 1 Vision and values ....................... 10 equality .......................................... 41 1.1 Norway and the United Nations .. 10 3.1 The international legal order ........ 41 1.1.1 Norway’s UN policy in a 3.1.1 The normative role of the UN ...... 41 changing world .............................. 10 3.1.2 Compliance with international 1.1.2 A well-equipped toolbox: the UN’s law .................................................... 42 many roles and functions .............. 11 3.1.3 The UN and the Law of the Sea .... 43 1.1.3 The shifting balance of power – 3.2 Human rights ................................. -

10 Things You Need to Know About NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Fact Sheet October 2016 10 things you need to know about NATO 1. An International Security Hub: The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is one of the world’s major international institutions. It is a political and military Alliance of 28 member countries from Europe and North America. The Alliance takes all its decisions by consensus. Every member country, no matter how large or small, has an equal say in discussions and decisions. Member states are committed to individual liberty, democracy, human rights and the rule of law. These values are at the heart of NATO’s transatlantic bond. 2. Collective Defence: The greatest responsibility of the Alliance is to protect and defend NATO’s territory and populations. Article 5 of NATO’s founding charter, the Washington Treaty, sets out the Alliance’s collective defence commitment. It states that an attack on one shall be considered an attack on all. Article 5 has been invoked only once in NATO’s history, on 12 September 2001, the day after the terrorist attacks on the United States. 3. NATO’s Command Structure: NATO has a permanent, integrated military command structure where military and civilian personnel from all member states work together. The Alliance has two top-level Strategic Commands (Allied Command Operations, in Mons, Belgium, and Allied Command Transformation, in Norfolk, United States). Under these Strategic Commands are two Joint Force Commands (in Brunssum, Netherlands and in Naples, Italy) that can deploy and run military operations. The Command Structure also includes one air command (Ramstein, Germany), one land command (Izmir, Turkey) and one maritime command (Northwood, United Kingdom). -

Assessing the Effectiveness of the United Nations Mission

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Thomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 The effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1.