Meld. St. 33 (2011–2012) Report to the Storting (White Paper)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 The first UN Infantry Battalion was deployed as part of United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF-I). UN infantry soldiers march in to Port Said, Egypt, in December 1956 to assume operational responsibility. asdf ‘The United Nations Infantry Battalion is the backbone of United Nations peacekeeping, braving danger, helping suffering civilians and restoring stability across war-torn societies. We salute your powerful contribution and wish you great success in your life-saving work.’ BAN Ki-moon United Nations Secretary-General United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual ii Preface I am very pleased to introduce the United Nations Infantry Battalion Man- ual, a practical guide for commanders and their staff in peacekeeping oper- ations, as well as for the Member States, the United Nations Headquarters military and other planners. The ever-changing nature of peacekeeping operations with their diverse and complex challenges and threats demand the development of credible response mechanisms. In this context, the military components that are deployed in peacekeeping operations play a pivotal role in maintaining safety, security and stability in the mission area and contribute meaningfully to the achievement of each mission mandate. The Infantry Battalion con- stitutes the backbone of any peacekeeping -

The Right to Peace, Which Occurred on 19 December 2016 by a Majority of Its Member States

In July 2016, the Human Rights Council (HRC) of the United Nations in Geneva recommended to the General Assembly (UNGA) to adopt a Declaration on the Right to Peace, which occurred on 19 December 2016 by a majority of its Member States. The Declaration on the Right to Peace invites all stakeholders to C. Guillermet D. Fernández M. Bosé guide themselves in their activities by recognizing the great importance of practicing tolerance, dialogue, cooperation and solidarity among all peoples and nations of the world as a means to promote peace. To reach this end, the Declaration states that present generations should ensure that both they and future generations learn to live together in peace with the highest aspiration of sparing future generations the scourge of war. Mr. Federico Mayor This book proposes the right to enjoy peace, human rights and development as a means to reinforce the linkage between the three main pillars of the United Nations. Since the right to life is massively violated in a context of war and armed conflict, the international community elaborated this fundamental right in the 2016 Declaration on the Right to Peace in connection to these latter notions in order to improve the conditions of life of humankind. Ambassador Christian Guillermet Fernandez - Dr. David The Right to Peace: Fernandez Puyana Past, Present and Future The Right to Peace: Past, Present and Future, demonstrates the advances in the debate of this topic, the challenges to delving deeper into some of its aspects, but also the great hopes of strengthening the path towards achieving Peace. -

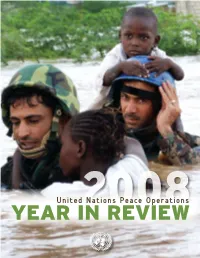

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Reputation As a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected]

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2019 Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2035 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, Organizations Law Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Daugirdas, Kristina. "Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations." Am. J. Int'l L. 113, no. 2 (2019): 221-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2019 by The American Society of International Law doi:10.1017/ajil.2018.122 REPUTATION AS A DISCIPLINARIAN OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS By Kristina Daugirdas* ABSTRACT As a disciplinarian of international organizations, reputation has serious shortcomings. Even though international organizations have strong incentives to maintain a good reputation, reputational concerns will sometimes fail to spur preventive or corrective action. Organizations have multiple audiences, so efforts to preserve a “good” reputation may pull organizations in many different directions, and steps taken to preserve a good reputation will not always be salutary. Recent incidents of sexual violence by UN peacekeepers in the Central African Republic illustrate these points. On April 29, 2015, The Guardian published an explosive story based on a leaked UN document.1 The document described allegations against French troops who had been deployed to the Central African Republic pursuant to a mandate established by the Security Council. -

Center News/Faculty and Staff Updates

Human Rights Brief Volume 17 | Issue 3 Article 13 2010 Center News/Faculty and Staff pU dates Human Rights Brief Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Human Rights Brief. "Center News/Faculty and Staff pdU ates." Human Rights Brief 17, no.3 (2010): 72-74. This Column is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Rights Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : Center News/Faculty and Staff Updates CENTER NEWS/FACULTY AND STAFF UPDATES ceNter NeWs Immigration and Customs Enforcement, of conduct that constitute customary law; U.S. Department of Homeland Security). the place of legal dualism in a mod- centeR’s progRam On Human neha Misra (Solidarity Center, AFL- ern constitutional state; intersections of tRafficking anD fORceD laBOR CIO), Ann Jordan, (Program Director, customary law and gender, particularly HOsts cOnfeRence examining OBama Center’s Program on Human Trafficking with respect to land tenure rights; and the aDministRatiOn’s approacH tO and Forced Labor), and Bama Athreya inclusion of customary law in national cOmBating tRafficking anD fORceD (International Labor Rights Forum) served and regional courts. sanele sibanda, lec- laBOR as moderators. turer at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, delivered the keynote The Center for Human Rights and speech on whether modern conceptions Humanitarian Law’s Program on Human u.s.-isRael civil liBeRties laW of democracy and human rights provide a Trafficking and Forced Labor, along with fellows progRam celeBRates 25 role for customary law in advancing human the International Labor Rights Forum yeaRs; professOR HeRman scHWaRtz rights or enriching the constitutional state. -

Report of the Regional Preparatory Conference for Africa

UNITED NATIONS A A/CONF.211/PC.3/4 Distr: General General Assembly 3 September 2008 Original: English Durban Review Conference Preparatory Committee Second substantive session Geneva, 6–17 October 2008 Item 3 of the provisional agenda Reports of preparatory meetings and activities at the international, regional and national levels Report of the Regional Preparatory Meeting for Africa for the Durban Review Conference (Abuja, 24–26 August 2008) Vice-Chair/Rapporteur: Ms. Cissy Taliwaku (Uganda) K0841735 260909 A/CONF.211/PC.3/4 Contents I. Final document of the Regional Preparatory Meeting for Africa for the Durban Review Conference......................................................................................................................................3 A. Review of progress and assessment of implementation of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action by all stakeholders at the national, regional and international levels, including the assessment of contemporary manifestations of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance............................................................5 B. Assessing, for the purpose of enhancing, the effectiveness of existing Durban Declaration and Programme of Action follow-up mechanisms and other United Nations mechanisms dealing with the issue of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance............................................................9 C. Promotion of the universal ratification and implementation of the International Convention on -

General Assembly 26 March 2010

United Nations A/RES/64/148 Distr.: General General Assembly 26 March 2010 Sixty-fourth session Agenda item 67 (b) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 18 December 2009 [on the report of the Third Committee (A/64/437)] 64/148. Global efforts for the total elimination of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance and the comprehensive implementation of and follow-up to the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action The General Assembly, Recalling its resolution 52/111 of 12 December 1997, in which it decided to convene the World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, and its resolutions 56/266 of 27 March 2002, 57/195 of 18 December 2002, 58/160 of 22 December 2003, 59/177 of 20 December 2004 and 60/144 of 16 December 2005, which guided the comprehensive follow-up to and effective implementation of the World Conference, and in this regard underlining the importance of their full and effective implementation, Welcoming the outcome of the Durban Review Conference convened in Geneva from 20 to 24 April 2009 within the framework of the General Assembly in accordance with its resolution 61/149 of 19 December 2006, Noting the approaching commemoration of the tenth anniversary of the 1 adoption of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action,0F Recalling all of the relevant resolutions and decisions of the Commission on Human Rights and of the Human Rights Council on this subject, and calling for their implementation to ensure the successful implementation of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action, 2 Noting Human Rights Council decision 3/103 of 8 December 2006,1F by which, heeding the decision and instruction of the World Conference, the Council established the Ad Hoc Committee of the Human Rights Council on the Elaboration of Complementary Standards, _______________ 1 See A/CONF.189/12 and Corr.1, chap. -

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook UNITED NATIONS FORCE HEADQUARTERS HANDBOOK November 2014 United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook Foreword The United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook aims at providing information that will contribute to the understanding of the functioning of the Force HQ in a United Nations field mission to include organization, management and working of Military Component activities in the field. The information contained in this Handbook will be of particular interest to the Head of Military Component I Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander and Force Chief of Staff. The information, however, would also be of value to all military staff in the Force Headquarters as well as providing greater awareness to the Mission Leadership Team on the organization, role and responsibilities of a Force Headquarters. Furthermore, it will facilitate systematic military planning and appropriate selection of the commanders and staff by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Since the launching of the first United Nations peacekeeping operations, we have collectively and systematically gained peacekeeping expertise through lessons learnt and best practices of our peacekeepers. It is important that these experiences are harnessed for the benefit of current and future generation of peacekeepers in providing appropriate and clear guidance for effective conduct of peacekeeping operations. Peacekeeping operations have evolved to adapt and adjust to hostile environments, emergence of asymmetric threats and complex operational challenges that require a concerted multidimensional approach and credible response mechanisms to keep the peace process on track. The Military Component, as a main stay of a United Nations peacekeeping mission plays a vital and pivotal role in protecting, preserving and facilitating a safe, secure and stable environment for all other components and stakeholders to function effectively. -

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook UNITED NATIONS FORCE HEADQUARTERS HANDBOOK November 2014 United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook Foreword The United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook aims at providing information that will contribute to the understanding of the functioning of the Force HQ in a United Nations field mission to include organization, management and working of Military Component activities in the field. The information contained in this Handbook will be of particular interest to the Head of Military Component I Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander and Force Chief of Staff. The information, however, would also be of value to all military staff in the Force Headquarters as well as providing greater awareness to the Mission Leadership Team on the organization, role and responsibilities of a Force Headquarters. Furthermore, it will facilitate systematic military planning and appropriate selection of the commanders and staff by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Since the launching of the first United Nations peacekeeping operations, we have collectively and systematically gained peacekeeping expertise through lessons learnt and best practices of our peacekeepers. It is important that these experiences are harnessed for the benefit of current and future generation of peacekeepers in providing appropriate and clear guidance for effective conduct of peacekeeping operations. Peacekeeping operations have evolved to adapt and adjust to hostile environments, emergence of asymmetric threats and complex operational challenges that require a concerted multidimensional approach and credible response mechanisms to keep the peace process on track. The Military Component, as a main stay of a United Nations peacekeeping mission plays a vital and pivotal role in protecting, preserving and facilitating a safe, secure and stable environment for all other components and stakeholders to function effectively. -

Protecting Civilians in the Context of UN Peacekeeping Operations

About this publication Since 1999, an increasing number of United Nations peacekeeping missions have been expressly mandated to protect civilians. However, they continue to struggle to turn that ambition into reality on the ground. This independent study examines the drafting, interpretation, and implementation of such mandates over the last 10 years and takes stock of the successes and setbacks faced in this endeavor. It contains insights and recommendations for the entire range of United Nations protection actors, including the Security Council, troop and police contributing countries, the Secretariat, and the peacekeeping operations implementing protection of civilians mandates. Protecting Civilians in the Context Protecting Civilians in the Context the Context in Civilians Protecting This independent study was jointly commissioned by the Department of Peace keeping Opera- Operations Peacekeeping UN of tions and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs of the United Nations. of UN Peacekeeping Operations Front cover images (left to right): Spine images (top to bottom): The UN Security Council considers the issue of the pro A member of the Indian battalion of MONUC on patrol, 2008. Successes, Setbacks and Remaining Challenges tection of civilians in armed conflict, 2009. © UN Photo/Marie Frechon. © UN Photo/Devra Berkowitz). Members of the Argentine battalion of the United Nations Two Indonesian members of the African Union–United Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) assist an elderly Nations Hybrid operation in Darfur (UNAMID) patrol as woman, 2008. © UN Photo/Logan Abassi. women queue to receive medical treatment, 2009. © UN Photo/Olivier Chassot. Back cover images (left to right): Language: ENGLISH A woman and a child in Haiti receive emergency rations Sales #: E.10.III.M.1 from the UN World Food Programme, 2008. -

MINORITY DEATH MATCH Jews, Blacks, And

September US Subs Cover Final2rev2 7/28/09 3:36 PM Page 1 SCENES FROM THE IRANIAN UPRISING HARPER’S MAGAZINE / SEPTEMBER 2009 $6.95 ◆ MINORITY DEATH MATCH Jews, Blacks, and the “Post-Racial” Presidency By Naomi Klein DEHUMANIZED When Math and Science Rule the School By Mark Slouka ADRIANA A story by J. M. Coetzee Also: Breyten Breytenbach and Richard Nixon ◆ REPORT MINORITY DEATH MATCH Jews, blacks, and the “post-racial” presidency By Naomi Klein When I arrived at the grand of- “Durban II,” this was the only United ing, why should they? And it could get fices of the United Nations High Nations gathering specifi cally focused worse, Pillay told me. “The E.U. states Commissioner for Human Rights, at on pushing governments to combat are meeting at 6:00 p.m. tonight, and the Palais Wilson, looking out at a racism inside their borders, a task that the Netherlands and Italy are likely to drizzly Lake Geneva, pull out.” She and U.N. Navanethem Pillay was Secretary-General Ban hunched over the Ki-moon had been on shoulder of her deputy, the phone with foreign Kyung-wha Kang, dic- ministers all day, trying tating a press release. “I to prevent the entire am shocked and deeply European Union from disappointed,” I heard walking out. Canada her say, pointing at the and Israel had pulled screen while Kang out months before. typed. It was 3:00 p.m., As Pillay was tally- and Pillay was having a ing up the damage, an very bad day. aide popped her head “Done,” she finally in the door: “The danc- declared, plopping down ers are here.” The high at her conference table. -

United Nations Development Action Framework 2013-17

INDIA UNDAF United Nations Development Action Framework 2013-2017 Cover Photo Credit: UNICEF and UNHCR Copyright: United Nations Resident Coordinator’s Office Formulated in 2011, printed in June 2012 INDIA UNDAF United Nations Development Action Framework 2013-2017 India UNDAF UnitedIndia UNDAF Nations UnitedDevelopment Nations Action Development Framework Action 2013-2017 Framework 2013-2017 2 Photo Credit: UNICEF India UNDAF United Nations Development Action Framework 2013-2017 Contents Foreword 4 India UNDAF 2013-2017 6 Executive Summary 7 1. Context 12 1.1 The UNDAF Formulation Process 12 1.2 Country Assessment 13 1.3 Lessons Learned from UNDAF 2008-12 18 1.4 The Comparative Advantage of the UN in India 19 1.5 The Vision and Mission of the UNDAF 20 1.6 Context and Focus of the UNDAF 21 2. The UNDAF Outcomes 22 2.1 Outcome 1: Inclusive Growth 22 2.2 Outcome 2: Food and Nutrition Security 30 2.3 Outcome 3: Gender Equality 34 2.4 Outcome 4: Equitable Access to Quality Basic Services [Health; Education; HIV and AIDS; Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH)] 40 2.5 Outcome 5: Governance 50 2.6 Outcome 6: Sustainable Development 54 3. Programme Implementation and Operations Management 60 3.1 Geographical Focus 60 3.2 Partnerships 61 3.3 Programme Management 61 3.4 Monitoring 63 3.5 Evaluation 64 3.6 Operations Management 64 4. Resource Requirements 66 Annexures Annexure 1: International Covenants/Conventions/Treaties Ratified/Acceded/Signed by India 68 Annexure 2: Terms of Reference for Programme Management Team (PMT) 70 Annexure 3: Terms of