This Interview Is Part of the Southern Oral History Program Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69 An Analysis of the Political Affiliations and Professions of Sunday Talk Show Guests Between the Obama and Trump Administrations Jack Norcross Journalism Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract The Sunday morning talk shows have long been a platform for high-quality journalism and analysis of the week’s top political headlines. This research will compare guests between the first two years of Barack Obama’s presidency and the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency. A quantitative content analysis of television transcripts was used to identify changes in both the political affiliations and profession of the guests who appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” CBS’s “Face the Nation,” ABC’s “This Week” and “Fox News Sunday” between the two administrations. Findings indicated that the dominant political viewpoint of guests differed by show during the Obama administration, while all shows hosted more Republicans than Democrats during the Trump administration. Furthermore, U.S. Senators and TV/Radio journalists were cumulatively the most frequent guests on the programs. I. Introduction Sunday morning political talk shows have been around since 1947, when NBC’s “Meet the Press” brought on politicians and newsmakers to be questioned by members of the press. The show’s format would evolve over the next 70 years, and give rise to fellow Sunday morning competitors including ABC’s “This Week,” CBS’s “Face the Nation” and “Fox News Sunday.” Since the mid-twentieth century, the overall media landscape significantly changed with the rise of cable news, social media and the consumption of online content. -

Remarks and an Exchange with Reporters on North Korea June 22, 1994

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1994 / June 22 best way to prove ourselves worthy of the legacy NOTE: The President spoke at 1:25 p.m. at the handed down by those who sacrificed in the Department of Veterans Affairs. In his remarks, Second World War, those who have worn our he referred to Garnett G. Shropshire, World War uniform since, and those who have been given II veteran, who introduced the President, and their just chance at the brass ring through the Hugo Mendoza, Persian Gulf war veteran. The bill of rights for the GI's. proclamation of June 21 on the 50th anniversary Thank you very much. of the GI bill of rights is listed in Appendix D at the end of this volume. Remarks and an Exchange With Reporters on North Korea June 22, 1994 The President. Good afternoon. Today I want will lead to the resolution of all the issues that to announce an important step forward in the divide Korea from the international community. situation in North Korea. This afternoon we In close consultation with our allies, we will have received formal confirmation from North continue as we have over the past year and Korea that it will freeze the major elements more to pursue our interests and our goals with of its nuclear program while a new round of steadiness, realism, and resolve. This approach talks between our nations proceeds. is paying off, and we will continue it. This is In response, we are informing the North Ko- good news. Our task now is to transform this reans that we are ready to go forward with a news into a lasting agreement. -

Opinion | Sylvia Chase and the Boys' Club of TV News

SUNDAY REVIEW Sylvia Chase and the Boys’ Club of TV News When we started at the networks in the early ’70s, most of us tried to hide our gender. Sylvia spoke out. By Lesley Stahl Ms. Stahl is a correspondent for “60 Minutes.” Jan. 12, 2019 Back in the early 1970s, the TV network news organizations wanted to show the world that they were “equal opportunity employers.” And so, CBS, ABC and NBC scoured the country for women and minorities. In 1971, Sylvia Chase was a reporter and radio producer in Los Angeles, and I was a local TV reporter in Boston. CBS hired her for the New York bureau; I was sent to Washington. Sylvia, who died last week at age 80, and I were CBS’s affirmative action babies, along with Connie Chung and Michele Clark. To ensure we had no illusions about our lower status, we were given the title of “reporter.” We would have to earn the position of “correspondent” that our male colleagues enjoyed. We were more like apprentices, often sent out on stories with the seniors, like Roger Mudd and Daniel Schorr. While we did reports for radio, the “grown-ups” — all men — did TV, but we were allowed to watch how they developed sources, paced their days and wrote and edited their stories. Up until then, most women in broadcast journalism were researchers. At first, the four of us in our little group were grateful just to be in the door as reporters. Things began to stir when the women at Newsweek sued over gender discrimination. -

News and Documentary Emmy Winners 2020

NEWS RELEASE WINNERS IN TELEVISION NEWS PROGRAMMING FOR THE 41ST ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED Katy Tur, MSNBC Anchor & NBC News Correspondent and Tony Dokoupil, “CBS This Morning” Co-Host, Anchor the First of Two Ceremonies NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 21, 2020 – Winners in Television News Programming for the 41th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy® Awards are being presented as two individual ceremonies this year: categories honoring the Television News Programming were presented tonight. Tomorrow evening, Tuesday, September 22nd, 2020 at 8 p.m. categories honoring Documentaries will be presented. Both ceremonies are live-streamed on our dedicated platform powered by Vimeo. “Tonight, we proudly honored the outstanding professionals that make up the Television News Programming categories of the 41st Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “As we continue to rise to the challenge of presenting a ‘live’ ceremony during Covid-19 with hosts, presenters and accepters all coming from their homes via the ‘virtual technology’ of the day, we continue to honor those that provide us with the necessary tools and information we need to make the crucial decisions that these challenging and unprecedented times call for.” All programming is available on the web at Watch.TheEmmys.TV and via The Emmys® apps for iOS, tvOS, Android, FireTV, and Roku (full list at apps.theemmys.tv). Tonight’s show and many other Emmy® Award events can be watched anytime, anywhere on this new platform. In addition to MSNBC Anchor and NBC. -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

December Sunday Morning Talk Shows December 5, 2010 24 Men and 8 Women

December Sunday Morning Talk Shows December 5, 2010 24 men and 8 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 5 men and 1 woman Sen. Mitch McConnell (M) Sen. John Kerry (M) David Brooks (M) Tom Friedman (M) Katty Kay (F) Mike Murphy (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 3 men and 1 woman Sen. Dick Durbin (M) Sen. Jon Kyl (M) Nancy Cordes (F) Jim VandeHei (M) ABC's This Week with Christiane Amanpour: 6 men and 3 women General Wesley Clark (M) Bob Maginnis (M) R. Clarke Cooper (M) Elaine Donnelly (F) Tammy Schultz (F) George Will (M) Zbigniew Brzezinski (M) Zalmay Khalilzad (M) Sakena Yacoobi (F) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 5 men and 0 women Sen. Orrin Hatch (M) Sen. Ron Wyden (M) Sen. Richard Lugar (M) Rep. Charlie Rangel (M) Jon Weiner (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 5 men and 3 women Sen. Kent Conrad (M) Rep. Jeb Hensarling (M) Newt Gingrich (M) Dana Perino (F) Nina Easton (F) Liz Cheney (F) Juan Williams (M) Dr. William Gahl (M) December 12, 2010 24 men and 5 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 5 men and 1 woman Austan Goolsbee (M) Mayor Michael Bloomberg (M) Rep. Anthony Weiner (M) former Rep. Harold Ford (M) Paul Gigot (M) Savannah Guthrie (F) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 3 men and 0 women David Axelrod (M) former Gov. Howard Dean (M) Rep. Jerold Nadler (M) ABC's This Week with Christiane Amanpour: 5 men and 2 women David Axelrod (M) Prime Minister Salam Fayyad (M) Tzipi Livni (F) George Will (M) Cokie Roberts (F) Matthew Dowd (M) Paul Krugman (M) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 5 men and 0 women David Axelrod (M) Rep. -

Religious Education

RELIGIOUS EDUCATION OF MANY THINGS ore than halfway through story that simply sells is clearly evident in 106 West 56th Street New York, NY 10019-3803 the general election, Donald much of what they do. Ph: (212) 581-4640; Fax: (212) 399-3596 Trump’s presidential campaign Scott Pelley, the veteran anchor of the Subscriptions: (800) 627-9533 M www.americamedia.org is imploding. The Republican flagship “CBS Evening News,” may not be the facebook.com/americamag resembles Jonah’s boat to Tarshish: most exciting personality on television, twitter.com/americamag but he is undoubtedly the best journalist, the tempest-tossed and panic-stricken PRESIDENT AND EDITOR IN CHIEF passengers are looking for someone to a worthy heir to the legacy of Paley, Matt Malone, S.J. blame, someone they can sacrifice to Murrow and Cronkite, something EXECUTIVE EDITORS their angry god. that Mr. Pelley takes seriously. He has Robert C. Collins, S.J., Maurice Timothy Reidy MANAGING EDITOR Kerry Weber Mr. Trump’s favorite scapegoat avoided blurring the line between news LITERARY EDITOR Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. these days is the national media. "If the and entertainment, saying that “there’s SENIOR EDITOR AND CHIEF CORRESPONDENT disgusting and corrupt media covered too much of a risk for the audience to Kevin Clarke me honestly and didn't put false meaning think ‘Wait a minute—is it scripted? Is EDITOR AT LARGE James Martin, S.J. CREATIVE DIRECTOR Shawn Tripoli into the words I say, I would be beating it not? Are you telling me the truth? Is it EXECUTIVE EDITOR, AMERICA FIlmS Hillary by 20 percent," he recently acting?’ That’s a big red line for me, and I Jeremy Zipple, S.J. -

Obamacare, the News Media, and the Politics of 21St-Century Presidential Communication

International Journal of Communication 9(2015), 1275–1299 1932–8036/20150005 Obamacare, the News Media, and the Politics of 21st-Century Presidential Communication JENNIFER HOPPER1 Washington College, USA Studies of presidential framing and the media lead to contrary expectations of whether the president would be able to reframe a pejorative name for a major legislative achievement and alter its news coverage. The case of President Obama and the use of the term “Obamacare” to refer to the Affordable Care Act requires rethinking what we know about presidential communication strategies and contemporary news norms. Obama’s embrace of the Obamacare moniker spread among supporters and led to its appearance with more positive/neutral depictions of the policy in the media. The term also has become more prominent in the news over time, raising questions about loosening standards of news objectivity and the future of this contested term. Keywords: presidency, news media, Affordable Care Act, Obamacare, presidential communication U.S. presidents face formidable challenges in attempting to frame policies and shape political debates, particularly in the 21st-century media environment. Given that presidential attempts to positively frame their positions for the media and the public require substantial time and effort with no guarantee of success, working to co-opt and reframe the established language of the president’s opponents is an even more daunting project. Yet this is precisely the endeavor President Barack Obama and his surrogates embarked on in late March 2012, when they embraced the term “Obamacare” and sought to use it in service of promoting and defending the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. -

October 18, 2009 Transcript

© 2009, CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved. PLEASE CREDIT ANY QUOTES OR EXCERPTS FROM THIS CBS TELEVISION PROGRAM TO "CBS NEWS' FACE THE NATION." October 18, 2009 Transcript GUESTS: RAHM EMANUEL White House Chief of Staff SENATOR JOHN CORNYN R-Texas SENATOR JOHN KERRY D-Massachusetts MODERATOR/ PANELIST: Mr. John Dickerson CBS News Political Analyst This is a rush transcript provided for the information and convenience of the press. Accuracy is not guaranteed. In case of doubt, please check with FACE THE NATION - CBS NEWS (202) 457-4481 TRANSCRIPT JOHN DICKERSON: Today on FACE THE NATION, White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel on Afghanistan, health care, and the economy. Plus, John Kerry from Afghanistan. President Obama is only weeks away from announcing whether he'll send thousands more troops to Afghanistan--could concerns over the unstable government there delay the decision, will he change strategy, and does the President have to step up his efforts on health care reform. We'll ask his chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel. We'll get reaction from Senator John Cornyn, Republican of Texas. And we'll talk to Senator John Kerry, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, who’s in Kabul, Afghanistan. But first, White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel on FACE THE NATION. ANNOUNCER: FACE THE NATION with CBS News chief Washington correspondent Bob Schieffer. And now from Washington, substituting for Bob Schieffer, CBS News political analyst John Dickerson. JOHN DICKERSON: With us now Rahm Emanuel, White House chief of staff. Welcome. RAHM EMANUEL (White House Chief of Staff): Thanks, John. -

Newspro Cuts a Wide Swath

December 2014 Entries Go to Great Lengths Longform Awards Submissions Reach New Heights Page 10 Footing the Innovation Bill Grant Programs Out to Blaze New Trails Page 12 A Children’s Cause Is Lost The Journalism Center on Children & Families Closes Its Doors Page 14 Our Top 10 J-Schools to Watch Mizzou Takes the No. 1 Spot Once Again 12 in TV News Page 16 Page 4 Plain Speaking on Integrity Author and Educator Charles Lewis Calls for Gravitas in Local Reporting Page 23 14np0054.pdf RunDate:12/15/14 Full Page Color: 4/C FROM THE EDITOR Loss or Gain, It’s Change e subject matter of this issue of NewsPro cuts a wide swath. We feature stories about disruptive change, about loss and gain, and about tradition and innovation. In essence, the terms that best describe the chaotic world of journalism. CONTENTS Our annual “12 to Watch in TV News” feature o ers a look at the professionals who are 12 TO WATCH IN TV NEWS ................. 4 in positions to make their imprint on — and in some cases change — the TV news business. This Year’s Wrap-up of the Pivotal Players You’ll nd among this year’s choices both the expected and a few fresh surprises. in the News Business On the journalism awards front, our piece discovers that the recession-related drop-o in submissions appears to be over for good, with programs reporting a notable gain in entries, AWARDS PROGRAMS ADAPT ........... 10 particularly of the longform variety — a development that has caused a dire need for change in Longform and Multimedia Entries Change the the way those organizations judge accomplishment. -

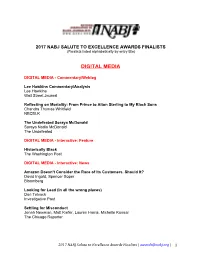

Digital Media

2017 NABJ SALUTE TO EXCELLENCE AWARDS FINALISTS (Finalists listed alphabetically by entry title) DIGITAL MEDIA DIGITAL MEDIA - Commentary/Weblog Lee Hawkins Commentary/Analysis Lee Hawkins Wall Street Journal Reflecting on Mortality: From Prince to Alton Sterling to My Black Sons Chandra Thomas Whitfield NBCBLK The Undefeated Soraya McDonald Soraya Nadia McDonald The Undefeated DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: Feature Historically Black The Washington Post DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: News Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of Its Customers. Should It? David Ingold, Spencer Soper Bloomberg Looking for Lead (in all the wrong places) Dan Telvock Investigative Post Settling for Misconduct Jonah Newman, Matt Kiefer, Lauren Harris, Michelle Kanaar The Chicago Reporter 2017 NABJ Salute to Excellence Awards Finalists | [email protected] | 1 DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: Feature The City: Prison's Grip on the Black Family Trymaine Lee NBC News Digital Under Our Skin Staff of The Seattle Times The Seattle Times Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement Eric Barrow New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: News Chicago's disappearing front porch Rosa Flores, Mallory Simon, Madeleine Stix CNN Machine Bias Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, Lauren Kirchner, Terry Parris Jr. ProPublica Nuisance Abatement Sarah Ryley, Barry Paddock, Pia Dangelmayer, Christine Lee ProPublica and The New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Single Story: Feature Congo's Secret Web of Power Michael Kavanagh, Thomas Wilson, Franz Wild Bloomberg Migration and Separation: