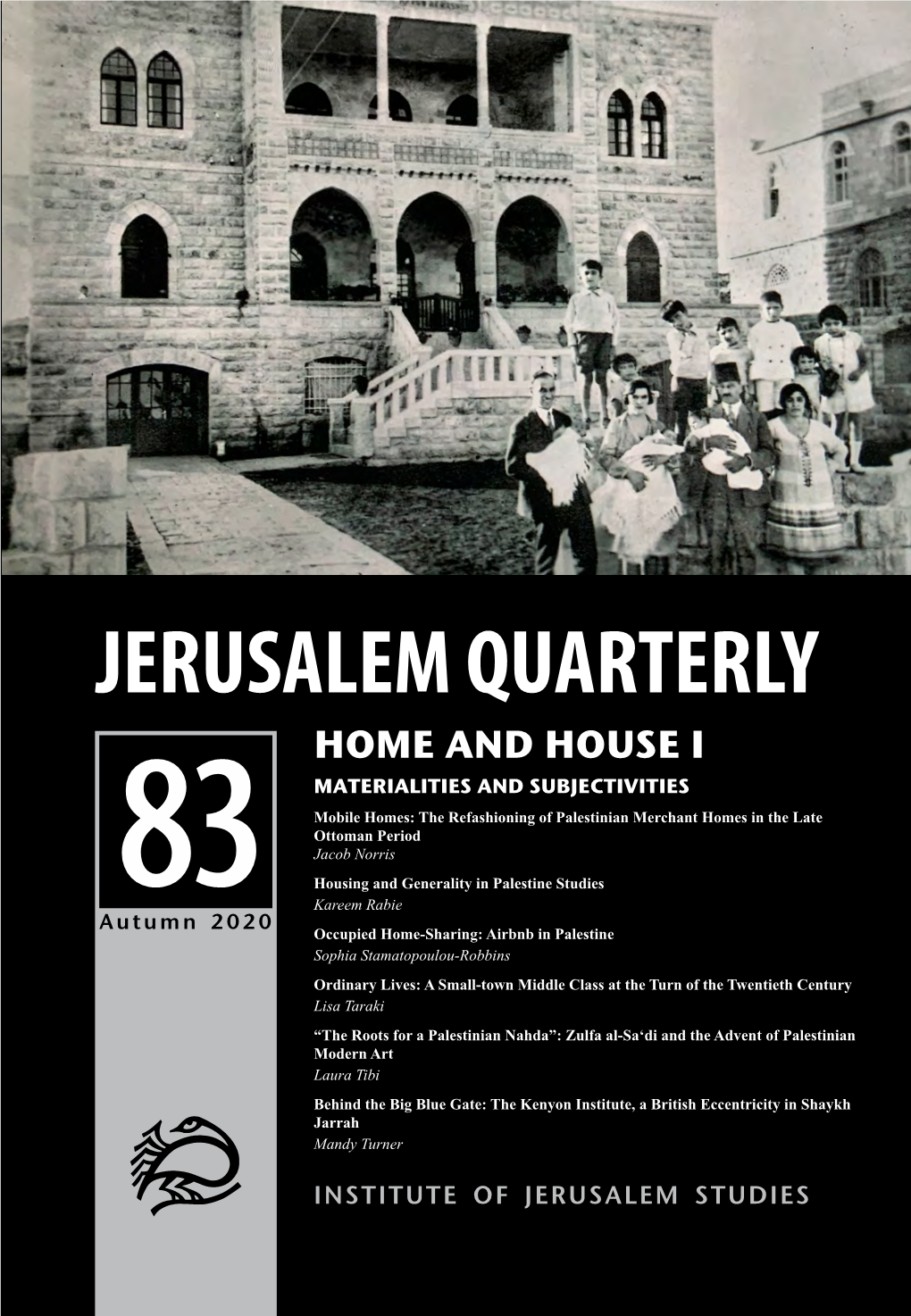

Home and House I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside Gaza: the Challenge of Clans and Families

INSIDE GAZA: THE CHALLENGE OF CLANS AND FAMILIES Middle East Report N°71 – 20 December 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION: THE DYNAMICS OF CHANGE ............................................... 1 II. THE CHANGING FORTUNES OF KINSHIP NETWORKS................................... 2 A. THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY AND CLAN POLITICS .............................................................2 B. THE 2000 UPRISING AND THE RISE OF CLAN POWER.............................................................3 C. ISRAEL’S GAZA DISENGAGEMENT AND FACTIONAL CONFLICT..............................................3 D. BETWEEN THE 2006 ELECTIONS AND HAMAS’S 2007 SEIZURE OF POWER.............................5 III. KINSHIP NETWORKS IN OPERATION .................................................................. 6 A. ECONOMIC SUPPORT .............................................................................................................6 B. FEUDS AND INFORMAL JUSTICE.............................................................................................7 C. POLITICAL AND SECURITY LEVERAGE...................................................................................9 IV. THE CLANS AND HAMAS........................................................................................ 13 A. BETWEEN GOVERNANCE AND CHAOS .................................................................................13 B. HAMAS’S SEIZURE OF POWER .............................................................................................14 -

Palestinians; from Village Peasants to Camp Refugees: Analogies and Disparities in the Social Use of Space

Palestinians; From Village Peasants to Camp Refugees: Analogies and Disparities in the Social Use of Space Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Maraqa, Hania Nabil Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 06:50:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/190208 PALESTINIANS; FROM VILLAGE PEASANTS TO CAMP REFUGEES: ANALOGIES AND DISPARITIES IN THE SOCIAL USE OF SPACE by Hania Nabil Maraqa _____________________ Copyright © Hania Nabil Maraqa 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 4 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to all those who made this research a reality. Special appreciation goes to my advisor, Dennis Doxtater, who generously showed endless support and guidance. -

Cultural Heritage for the Future

Sida Evaluation 04/30 Cultural Heritage for the Future An Evaluation Report of Nine years’ work by Riwaq for the Palestinian Heritage 1995–2004 Lennart Edlund Department for Democracy and Social Development Cultural Heritage for the Future An Evaluation Report of Nine years’ work by Riwaq for the Palestinian Heritage 1995–2004 Lennart Edlund Sida Evaluation 04/30 Department for Democracy and Social Development This report is part of Sida Evaluations, a series comprising evaluations of Swedish development assistance. Sida’s other series concerned with evaluations, Sida Studies in Evaluation, concerns methodologically oriented studies commissioned by Sida. Both series are administered by the Department for Evaluation and Internal Audit, an independent department reporting directly to Sida’s Board of Directors. This publication can be downloaded/ordered from: http://www.sida.se/publications Author: Lennart Edlund The views and interpretations expressed in this report are the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida Evaluation 04/30 Commissioned by Sida, Department for Democracy and Social Development and Department for Africa Copyright: Sida and the author Registration No.: 2003-2425 Date of Final Report: June 2004 Printed by Edita Sverige AB, 2004 Art. no. Sida4374en ISBN 91-586-8494-8 ISSN 1401—0402 SWEDISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AGENCY Address: SE-105 25 Stockholm, Sweden. Office: Sveavägen 20, Stockholm Telephone: +46 (0)8-698 50 00. Telefax: +46 (0)8-20 88 64 E-mail: [email protected]. Homepage: http://www.sida.se Table of Contents Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 1. Background ......................................................................................................... 8 1.1 The threat to cultural heritage............................................................................................ -

Cultural Heritage in Palestine RIWAQ New Experience and Approaches

Cultural Heritage in Palestine RIWAQ New Experience and Approaches Nazmi Ju’beh∗ Ramallah-Palestine June 2009 Introduction Cultural Heritage in Palestine was for more than one century a monopole of western foreign scholarship. It is just in the last two decades that Palestinians began to establish national infrastructure to deal with the different components of cultural heritage. The terminology “cultural heritage” in itself is also very recent, the locally used terminologies were “antiquities” and “heritage”. The first terminology was a legal one, meaning all kinds of movable and immovable remains of cultural heritage which existed before the year 1700, and for local Palestinian population it meant a source of income, either through working for foreign missions as cheap unskilled labor or through illicit excavations, selling the artifacts in the black market. The second terminology was nothing except ethnographic objects with a lot on nostalgia meanings. In the last two decades a tremendous development, in spite of all kinds of difficulties, took place in Palestine. The experience is in general very recent, but very rich and the number of involved institutions is growing rapidly; as well do the number of involved individuals in different components of cultural heritage. It is very important to bear in mind that cultural heritage in Palestine, unfortunately, is still a very sensitive, ideologically and politically oriented “science” and practice. Cultural heritage research in Palestine is to be understood in the context of the area’s historic developments since 1850 until today. Therefore, to process the history of the various groups, whether local or foreign, it is important to examine the historical factors that have developed in the area. -

Riwaq's Policy Document

A Policy Document Cultural heritage: a tool for development The Rehabilitation of Historic Centers and Buildings in the occupied Palestinian territories Prepared by: Suad Amiry and Farhat Muhawi Riwaq: Center for Architectural Conservation Date: April 2008 1 Cultural heritage a tool for development Introduction The main objective of this document is to explore how the Cultural Heritage Sector (CHS) in the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt) could become an important tool for social and economic development. This paper proposes a framework for structuring a national policy document that deals with the protection, rehabilitation and development of the CHS in the oPt; thus, this is a policy document that addresses cultural heritage issues and approaches. Hopefully, with the support of the UNDP, this document will stimulate much needed debate amongst all relevant stakeholders in the field of cultural heritage and such dialogue can lead to a communal understanding and vision towards placing the cultural heritage sector on the national agenda of the PNA and thereby on that of funding agencies. It is hoped that such methodical / systematic discussions will form a foundation for a shared message that would ultimately define a Palestinian program and aid in the realization of better / more effective results in the field of architectural heritage. The CHS has traditionally and continues to be viewed as an economic liability rather than as an important tool for economic and social development. Despite the huge amount of activity and the numerous governmental and non-governmental organizations working in the CHS for the last two decades, no collective effort has focused on establishing policy guidelines to outline priorities and provide an appropriate methodology for this sector. -

Tentative States of Heritage Facts-In-The Ground As Facts-On-The-Ground in the Tentative Lists of Israel and Palestine

Tentative States of Heritage Facts-in-the ground as facts-on-the-ground in the Tentative Lists of Israel and Palestine Robin Barnholdt Degree project for Master of Science (Two Year) in Conservation 60 hec Department of Conservation University of Gothenburg 2015:26 Tentative States of Heritage Facts-in-the ground as facts-on-the-ground in the Tentative Lists of Israel and Palestine Robin Barnholdt Supervisor: Valdimar Tr. Hafstein Degree project for Master of Science (Two Year) in Conservation UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG ISSN 1101-3303 Department of Conservation ISRN GU/KUV—15/26—SE UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG http://www.conservation.gu.se Department of Conservation Fax +46 31 7864703 P.O. Box 130 Tel +46 31 7864700 SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Master’s Program in Conservation, 120 hec By: Robin Barnholdt Supervisor: Valdimar Tr. Hafstein Tentative States of Heritage - Facts-in-the-ground as facts-on-the-ground in the Tentative Lists of Israel and Palestine ABSTRACT In 2011 Palestine became a member state of UNESCO and ratified the World Heritage Convention. When Palestine became a State Party of the convention a new arena, the super bowl of cultural heritage, known as the World Heritage List occurred for the heritage sector for Palestine. In this arena the conflicting states of the Holy Land, Israel and Palestine, are equals. This thesis presents the properties listed on the Tentative Lists (the list from which properties for the World Heritage List are chosen) of Israel and Palestine and it compares the two lists with focus on the presentation of history and how it is used to claim the same land. -

Mobilizing Movements, Mobilizing Contemporary Islamic Resistance

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2008 Mobilizing movements, mobilizing contemporary Islamic resistance Rachael M. Rudolph West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rudolph, Rachael M., "Mobilizing movements, mobilizing contemporary Islamic resistance" (2008). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4418. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4418 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mobilizing Movements, Mobilizing Contemporary Islamic Resistance Rachael M. Rudolph Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Scott Crichlow, Ph.D, Co-Chair Jeffrey Worsham, Ph.D Co-Chair Joe Hagan, Ph.D Robert Duval, Ph.D Abdul Karim Bangura, Ph.D Department of Political Science Morgantown, West Virginia 2008 Keywords: Social Movements, Islamic Resistance, Mobilization Copyright 2008, Rachael M. Rudolph ABSTRACT Mobilizing Movements, Mobilizing Islamic Resistance Rachael M. -

Palestinian Identity and Cultural Heritage1 Nazmi Al-Ju’Beh

Palestinian Identity and Cultural Heritage1 Nazmi Al-Ju’beh Introduction 1It is vital to differentiate between identity and identities. The difference between the terminologies is not simply that between singular and plural, it reaches far beyond, to a more philosophical approach, a way of life, and reflects the structure of a society and its political aspirations. It is therefore very difficult, perhaps impossible, to tackle the identity of a people as such, as if we were exploring one homogeneous entity, a clear-cut definition, accepted comfortably by the community/communities that formulate the society/the state/the nation. Before discussing Palestinian identity, it is important to address some basic and theoretical frameworks in a historical context. 2History is considered the main container of identity. Nations are rewriting their history/histories in order to explain and adapt contemporary developments, events, and phenomena, in order to employ them in the challenges facing the society, and also to reflect the ideology of the ruling class. It is, without hesitation, a difficult task, to trace one identity of a people through history; hence, identity, like any other component of a society, is very flexible, variable, and mobile and of course it reflects historical conditions. The formation of identity/identities commonly takes place in an intensive manner during conflicts and challenges, since it is important, in such circumstances, to clarify and to underline the common elements among certain groups of people that are adequate and can be mobilized facing the specific challenge. 3The understanding will not be exact if the process of formation of a nation is limited to conflicts and challenges only. -

Protecting Palestinian Children from Political Violence the Role of the International Community

FORCED MIGRATION POLICY BRIEFING 5 Protecting Palestinian children from political violence The role of the international community Authors Dr Jason Hart Claudia Lo Forte September 2010 Refugee Studies Centre Oxford Department of International Development University of Oxford Forced Migration Policy Briefings The Refugee Studies Centre’s (RSC) Forced Migration Policy Briefings seek to highlight the very best and latest policy-relevant research findings from the fields of forced migration and humanitarian studies. The Policy Briefings are designed to influence a wide audience of policy makers and humanitarian practitioners in a manner that is current, credible and critical. The series provides a unique forum in which academic researchers, humanitarian practitioners, international lawyers and policy makers may share evidence, experience, best practice and innovation on the broad range of critical issues that relate to forced migration and humanitarian intervention. The Refugee Studies Centre invites the submission of policy briefings on all topics of relevance to policy and practice in the fields of forced migration, refugee protection and humanitarian intervention. Further details may be found at the RSC website (www.rsc.ox.ac.uk). If you have a paper for submission, or a proposal for a Policy Brief that you would like to discuss with the editor, Héloïse Ruaudel, please contact [email protected] The series is supported by the UK Department For International Development(DFID). The opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and should not be attributed to DFID, the Refugee Studies Centre or to the University of Oxford as a whole. The research that informs this Policy Briefing was supported by the East-West Trust and the Council for British Research in the Levant. -

I the UNIVERSITY of CHICAGO BEYOND the WALLS of JERICHO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO BEYOND THE WALLS OF JERICHO: KHIRBET AL-MAFJAR AND THE SIGNATURE LANDSCAPES OF THE JERICHO PLAIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY MICHAEL DEAN JENNINGS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2015 i Copyright © 2015 by Michael Dean Jennings. All rights reserved. ii To Mom and Dad x 2 “Potrei dirti di quanti gradini sono le vie fatte a scale, di che sesto gli archi dei porticati, di quali lamine di zinco sono ricoperti i tetti; ma so già che sarebbe come non dirti nulla. Non di questo è fatta la città, ma di relazioni tra le misure del suo spazio e gli avvenimenti del suo passato.” “I could tell you how many steps make up the streets rising like stairways, and the degree of the arcades’ curves, and what kind of zinc scales cover the roofs; but I already know this would be the same as telling you nothing. The city does not consist of this, but of relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past.” Italo Calvino, Le città invisibili iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF PLATES ......................................................................................................................... ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... -

A B C Chd Dhe FG Ghhi J Kkh L M N P Q RS Sht Thu V WY Z Zh

Arabic & Fársí transcription list & glossary for Bahá’ís Revised September Contents Introduction.. ................................................. Arabic & Persian numbers.. ....................... Islamic calendar months.. ......................... What is transcription?.. .............................. ‘Ayn & hamza consonants.. ......................... Letters of the Living ().. ........................ Transcription of Bahá ’ı́ terms.. ................ Bahá ’ı́ principles.. .......................................... Meccan pilgrim meeting points.. ............ Accuracy.. ........................................................ Bahá ’u’llá h’s Apostles................................... Occultation & return of th Imám.. ..... Capitalization.. ............................................... Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ week days.. .............................. Persian solar calendar.. ............................. Information sources.. .................................. Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ months.. .................................... Qur’á n suras................................................... Hybrid words/names.. ................................ Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ years.. ........................................ Qur’anic “names” of God............................ Arabic plurals.. ............................................... Caliphs (first ).. .......................................... Shrine of the Bá b.. ........................................ List arrangement.. ........................................ Elative word -

The Adaptive Use of Historic Buildings

Annual Report 2012 A Word from RIWAQ Heritage in Palestine: new cartography and spatial justice 2012 has been a productive year for RIWAQ. architecture initiatives that rendered RIWAQ’s RIWAQ carried out numerous restoration and restoration sites into life size laboratories. Beit regeneration projects, implemented the 4th Ur Community Center, Salfit Women’s Center, RIWAQ Biennale, adventured into green archi- and Beit Iksa restoration projects served as pi- tecture initiatives, and celebrated new partner- lots for these initiatives that tried to upcycle ships and collaborations. materials and use rammed earth, dry stone and sun dried mud bricks as well as recycle grey wa- RIWAQ continued to manage, through different ter for irrigation while collecting and using rain- funds, to help communities in marginalized ar- water. eas of the West Bank by creating thousands of workdays, and transforming run down spaces RIWAQ continues to see some of its main re- into hubs of culture and production. The wom- sponsibilities as setting examples that work to en’s centers in Salfit, Tulkarem, and Deir Ghas- rationalize the limited resources, to capitalize saneh as well as the Fair Trade in Nisf Jbeil are on former experiences, and to take restoration examples of utilizing heritage to help the less to levels beyond the technical, thereby tack- Vision: a cultural and natural heritage that enjoys protection, is alive fortunate segments of the Palestinian popula- ling the socio-economic-political questions in and active in the development process in Palestine. A heritage that tes- tion, triggering new dynamics of socio-econom- everyday life. In so doing, RIWAQ engages the tifies to and strengthens the Palestinian national identity and its natural ic development.