UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Sorority Looks to Raise Money

UNIVERSITY ouSuunews.comrnal Cedar City, Utah J Southern Utah University Thursday, March 31, 2016 Sorority looks to raise money By MARIAH TUCKER Omega president; and Katie Berrie, Alpha Phi president, [email protected] all had jars for donations on SUU’s sorority Delta Psi the table this week. The person Omega is using its philanthropy whose name was on the jar week to raise money for the with the most money will be American Cancer Society. chosen to sing. Each Greek organization on Sam Carlin, a sophomore campus has a philanthropy theatre education major week where they raise from West Haven, was in money to help a charity charge of planning this year’s the organization chooses. philanthropy week and said Members work together to she chose the American Cancer reach their fundraising goal Society as the beneficiary throughout the week in the of the funds because of the different events. connections that she has as Delta Psi Omega set a goal well as the connections other of $1,500 it wanted to raise students may have. through tabling, where sorority “It helps bring all of us members collect donations at a together,” Carlin said. “It table set up in the main hallway also helps people to realize in the Sharwan Smith Student that we all have a connection Center and other activities to cancer.” during the week. Sorority Along with tabling, Delta Psi members have tabled in the Omega asked for donations main hallway in the Sharwan door to door, had a bake sale Smith Student Center every Wednesday, will have the lip day so far this week, and will sync battle tonight at 6:30 p.m. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Salvage Tourism in American Indian Historical Pageantry A

“We All Have a Part to Play”: Salvage Tourism in American Indian Historical Pageantry A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY KATRINA MARGARET-MARIE WILBER PHILLIPS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Adviser: JEAN O’BRIEN MAY 2015 Acknowledgements I am, like my father, often stubborn and independent. However, as I have been reminded time and time again throughout this humbling and gratifying journey, I just can’t do it alone. First and foremost, there is my adviser, Jeani O’Brien, who has read every single word I have ever written – many of them multiple times over. I am eternally grateful for the ways in which she has motivated me, encouraged me, and guided me throughout my graduate school career. I can never repay her for the time she has dedicated to me, and I thank you from the bottom of my heart. David Chang has pushed me to challenge myself and expand my horizons, which has made me a better scholar. I thank David as well as Kat Hayes for serving as my reviewers, and their feedback was instrumental in shaping this final product. Kevin Murphy and Brenda Child have also kindly served on my committees, and I truly appreciate their time and insight. Barbara Welke’s comments during my preliminary exams urged me to look beyond the scope of my initial research. Any errors in the final product, though, are mine and mine alone. The American Indian and Indigenous Studies Workshop has been my academic home since my first year of graduate school – and special thanks to Boyd Cothran, who helped me with my senior undergraduate thesis and my graduate school applications. -

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Sayaw Filipino: a Study of Contrasting Representations of Philippine Culture

SAYAW FILIPINO: A STUDY OF CONTRASTING REPRESENTATIONS OF PHILIPPINE CULTURE BY THE RAMON OBUSAN FOLKLORIC GROUP AND THE BAYANIHAN PHILIPPINE NATIONAL FOLKDANCE COMPANY KANAMI NAMIKI B.A. Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2007 Acknowledgement First of all, I would like to thank the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore, for the generous grants and the opportunity they gave me to study at the university and write this research thesis. I wish to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Reynaldo Ileto, who gave me valuable direction and insights and much-needed encouragement and inspiration. I applied to NUS because I wanted to learn and write my thesis under his supervision, and I have indeed learned a lot from him. I would like to also thank co-supervisor, Dr. Jan Mrazek, for his helpful advice and refreshing and insightful approach to the study of performing arts. It has been my great fortune to have Nikki Briones as my classmate and friend, and regular discussion-mate at NUS. She helped me articulate my thoughts and I am indebted to her for reading my draft and providing valuable suggestions, though she was also busy writing her own dissertation. I would like to also thank following individuals who gave me the support and advice over the years: Dr. Michiko Yamashita of the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies; Dr. Hiromu Shimizu of the Kyoto University; Dr. Takefumi Terada of the Sophia University; Dr. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

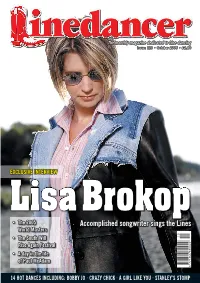

Accomplished Songwriter Sings the Lines

ThemonthlymagazinededicatedtoLinedancingThe monthly magazine dedicated to Line dancing Issue:113•October2005•£2.80Issue: 113 • October 2005 • £2.80 EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW Lisa Brokop • The 2005 Accomplished songwriter sings the Lines World Masters • The South Will 10 Rise Again Festival • AdayinthelifeA day in the life of Paul McAdam 9 771366 650024 14 HOT DANCES INCLUDING: BOBBY JO · CRAZY CHICK · A GIRL LIKE YOU · STANLEY’S STOMP 92860 OCTOBER 2005 Editorial and Advertising Clare House Dear Dancers 166 Lord Street Southport, PR9 0QA It’s a changing world and we have to move with the times. Tel: 01704 392300 Fax: 01704 501678 As our readers know, this magazine is produced by a handful Subscription Enquiries of dedicated people. We all love working on the magazine and Tel: 01704 392339 thoroughly enjoy putting it together from all the information [email protected] you send each month. It’s a joy to be a part of that process and speaking personally, I am lucky to be able to combine my Agent Enquiries career and my hobby in a way that allows me to deliver a top Michael Hegarty • Tel: 0161 281 6441 quality magazine for Line dancers. [email protected] Publisher Linedancer has been the centre of our world for nine years and Betty Drummond no doubt it will always remain so. However, it is a changing [email protected] world and the Internet has made a major change to the way The Linedancer Team we bring you information. As publishers, we must be just as committed to the standard of your website as we are to the Acting Editor standard of your magazine. -

Pamela 6 Ans Mairie De Plant Capitale De La Fraise En Floride

Pamela 6 ans Mairie de Plant capitale de la fraise en Floride Pamela Yvonne dit "Pam" Tillis est née le 24 Juillet 1957 à Plant City en Floride. Plant City est une ville du comté de Hillsborough, en Floride, située à mi-chemin entre Brandon et Lakeland. Pam est auteur compositeur interprète en country music. Elle a repoussé les limites du genre en intégrant la pop, le jazz, le blues et des influences folk y compris des touches HonkyTonk. A 4 ans elle commence à écrire des chansons et à les interpréter pour sa maitresse, lorsqu‟elle était à l‟école maternelle. Elle étudie le piano classique à 8 ans et prend des cours de guitare à 11ans. Elle écrit les textes de ses chansons à 13 ans et les interprétera dans des clubs vers 15 ans. Ainée de cinq enfants la chanteuse country Pam Tillis n'a pas eu une enfance heureuse ; ses parents se séparent et elle doit souvent s‟occuper de ses frères et sœurs. Tout d‟abord, elle ne voulait pas suivre les traces de son père artiste, même si elle avait l‟ambition de chanter et d‟écrire ses chansons. Elle grandit à Nashville et fait ses débuts au Grand Ole Opry à 8 ans, en interprétant "Tom Dooley‟‟. A 16 ans, elle est blessée dans un accident de voiture et subit plusieurs interventions chirurgicales pour une reconstruction faciale. Pam s'inscrit à l‟Université du Tennessee et joue parallèlement à ses études dans deux groupes locaux: un jug band appelé le „‟High Country Swing Band‟‟ et chante en duo avec la chanteuse „‟Ashley Cleveland‟‟.