P O R O S I T Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glitz and Glam

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:17 PM Glitz and glam The biggest celebration in filmmaking tvspotlight returns with the 90th Annual Academy Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Awards, airing Sunday, March 4, on ABC. Every year, the most glamorous people • For the week of March 3 - 9, 2018 • in Hollywood stroll down the red carpet, hoping to take home that shiny Oscar for best film, director, lead actor or ac- tress and supporting actor or actress. Jimmy Kimmel returns to host again this year, in spite of last year’s Best Picture snafu. OMNI Security Team Jimmy Kimmel hosts the 90th Annual Academy Awards Omni Security SERVING OUR COMMUNITY FOR OVER 30 YEARS Put Your Trust in Our2 Familyx 3.5” to Protect Your Family Big enough to Residential & serve you Fire & Access Commercial Small enough to Systems and Video Security know you Surveillance Remote access 24/7 Alarm & Security Monitoring puts you in control Remote Access & Wireless Technology Fire, Smoke & Carbon Detection of your security Personal Emergency Response Systems system at all times. Medical Alert Systems 978-465-5000 | 1-800-698-1800 | www.securityteam.com MA Lic. 444C Old traditional Italian recipes made with natural ingredients, since 1995. Giuseppe's 2 x 3” fresh pasta • fine food ♦ 257 Low Street | Newburyport, MA 01950 978-465-2225 Mon. - Thur. 10am - 8pm | Fri. - Sat. 10am - 9pm Full Bar Open for Lunch & Dinner FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:19 PM 2 • Newburyport Daily News • March 3 - 9, 2018 the strict teachers at her Cath- olic school, her relationship with her mother (Metcalf) is Videoreleases strained, and her relationship Cream of the crop with her boyfriend, whom she Thor: Ragnarok met in her school’s theater Oscars roll out the red carpet for star quality After his father, Odin (Hop- program, ends when she walks kins), dies, Thor’s (Hems- in on him kissing another guy. -

Annual Report

ANNU2009AL REPORT S ONTENT C 2 From the President 5 Past Presidents 6 Office Bearers & Staff 8 Honour Roll Sub Committee Reports 10 Track & Field 13 Cross Country & Road Racing 17 Officials 21 Records 24 Statistics 25 Tracks Management Reports 26 From the Chief Executive 28 Programs 30 Development 36 Competition ANNUAL REPORT Competition Awards 40 XCR Awards 42 Summer Awards 44 Membership Statistics 46 Victorian Institute of Sport 48 Financial Report 2009 mission: to encourage, improve, promote and manage athletics in victoria. we will: .encourage participation in athletics by all people .provide for the development of athletes at all levels of ability from beginners to elite .increase the profile and awareness of athletics within the community .provide for the development of coaches, officials, administrators and other volunteers in athletics .provide financial ANNU2009AL REPORT viability From the President ANNE LORD, PRESIDENT, ATHLETICS VICTORIA Athletics Victoria continues to enjoy growth in Congratulations all aspects of our sport. Participation numbers continue to climb steadily. Financial growth has Not everyone can be publically applauded, but been important. AV needs to increase its surplus I would like to congratulate Pam Noden, John in order to maintain many of the programs Coleman and Martyn Kibel on their Official of previously supported by the government’s the Year awards. Moving Athletics Forward funding. Two of our members were recognized in the The continued growth of our sport over the Queen’s birthday honours. Congratulations past few years is due in part to a resurgence of to Paul Jenes and Ronda Jenkins who were athletics and running’s popularity amongst the both awarded the OAM for their contribution general public but also because of the great to athletics. -

Athletics Australia Almanac

HANDBOOK OF RECORDS & RESULTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to the following for their support and contribution to Athletics Australia and the production of this publication. Rankings Paul Jenes (Athletics Australia Statistician) Records Ronda Jenkins (Athletics Australia Records Officer) Results Peter Hamilton (Athletics Australia Track & Field Commission) Paul Jenes, David Tarbotton Official photographers of Athletics Australia Getty Images Cover Image Scott Martin, VIC Athletics Australia Suite 22, Fawkner Towers 431 St Kilda Road Melbourne Victoria 3004 Australia Telephone 61 3 9820 3511 Facsimile 61 3 9820 3544 Email [email protected] athletics.com.au ABN 35 857 196 080 athletics.com.au Athletics Australia CONTENTS 2006 Handbook of Records & Results CONTENTS Page Page Messages – Athletics Australia 8 Australian Road & Cross Country Championships 56 – Australian Sports Commission 10 Mountain Running 57 50km and 100km 57 Athletics Australia Life Members & Merit Awards 11 Marathon and Half Marathon 58 Honorary Life Members 12 Road Walking 59 Recipients of the Merit Award of Athletics Australia 13 Cross Country 61 All Schools Cross Country 63 2006 Results Australian All Schools & Youth Athletics Championships 68 Telstra Selection Trials & 84th Australian Athletics Championships 15 Women 69 Women 16 Men 80 Men 20 Schools Knockout National Final 91 Australian Interstate Youth (Under 18) Match 25 Cup Competition 92 Women 26 Plate Competition 96 Men 27 Telstra A-Series Meets (including 2007 10,000m Championships at Zatopek) 102 -

Media Kit 2020

SYDNEY MEDIA KIT 2020 www.wheretraveller.com Photo: © Hugh Stewart/Destination NSW. The tourism market in VISITORS* SPEND In2019 $34billion 41.5 million visited PER YEAR Sydney the greater Sydney region IN SYDNEY *International and domestic INTERNATIONAL The Gateway to Australia % VISITOR OVERNIGHT VISITORS NUMBERS TO AUSTRALIA SPEND Most international visitors 40 INCREASED TRIPS REPRESENT arrive in Sydney first when LEISURE TRAVEL % % they come to Australia. 11 BETWEEN 39 2018-19 OF THEIR DOLLARS IN SYDNEY 3.1 NIGHTS 37.9the million average visitors to 1 = China 2 = USA the greaterduration Sydney of stay region TOURIST 3 = New Zealand SPENDING: 4 = United Kingdom Record growth of domestic and TOP 5 5 = South Korea international visitors year on year NATIONALITIES Photo: Destination NSW. Sources: Destination NSW and Tourism Research Australia wheretraveller.com Print: a trusted and versatile media solution We can create diverse media READERS ARE products to make your campaign % effective such as advertorials, inserts, magazine covers, editorial 70 listings and much more. MORE LIKELY TO RECALL YOUR • In-r oom placement in BRAND IN PRINT (source: Forbes) 5, 4.5 and 4 star hotels for guaranteed visibility to the lucrative visitor market WHERETRAVELLER MAGAZINE • We can create custom content READERSHIP: • Diverse and current coverage across bars, restaurants, 226,000 entertainment, shopping, PER MONTH sightseeing and more WhereTraveller products are supported by Les Clefs d’Or Australia, the International Concierge Society wheretraveller.com WhereTraveller Magazine: the complete guide WhereTraveller Magazine is a monthly guidebook-style magazine that readers can easily take with them when they explore each city’s top restaurants, shops, shows, attractions, exhibits and tours. -

Table of Contents

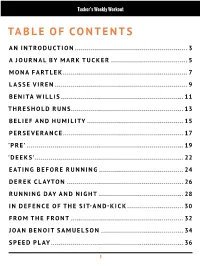

Tucker’s Weekly Workout TABLE OF CONTENTS AN INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 3 A JOURNAL BY MARK TUCKER ...................................... 5 MONA FARTLEK .............................................................. 7 LASSE VIREN .................................................................. 9 BENITA WILLIS ............................................................. 11 THRESHOLD RUNS........................................................ 13 BELIEF AND HUMILITY ................................................ 15 PERSEVERANCE ............................................................ 17 'PRE' .............................................................................. 19 'DEEKS' .......................................................................... 22 EATING BEFORE RUNNING .......................................... 24 DEREK CLAYTON .......................................................... 26 RUNNING DAY AND NIGHT .......................................... 28 IN DEFENCE OF THE SIT-AND-KICK ............................ 30 FROM THE FRONT ........................................................ 32 JOAN BENOIT SAMUELSON ......................................... 34 SPEED PLAY .................................................................. 36 2 Tucker’s Weekly Workout AN INTRODUCTION There is no one size fits all when it comes to training. We all have different biomechanics, psychology, motivations, backgrounds, personalities and general life situations that it would be foolish to think -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

Airport OLS Penetrations by Existing and Planned Structures in the Sydney and Brisbane CBD

1 Airport OLS Penetrations by Existing and Planned Structures in the Sydney and Brisbane CBD It is crucial that the safety implications arising from the recent incidents involving a Qantas airbus A380 following take-off at Singapore airport on the 4th of November, 2010 and a B747 departing the same airport two days later are fully appreciated by governments at all levels. Although the problems were serious enough, they could have been a lot worse and could well have occurred at Brisbane or Sydney airports. To further illustrate what happened to the A380, the following interim list of 18 items damaged by the exploding engine was released to the media on the 11/11/2010. 1.Massive fuel leak in the left mid fuel tank (there are 11 tanks, including in the horizontal stabiliser on the tail); 2.Massive fuel leak in the left inner fuel tank; 3. A hole on the flap fairing big enough to climb through; 4 The aft gallery in the fuel system failed, preventing many fuel transfer functions; 5 Problem jettisoning fuel; 6 Massive hole in the upper wingsurface; 7 Partial failure of leading edge slats; 8 Partial failure of speed brakes/groundspoilers; 9 Shrapnel damage to the flaps; 10 Total loss of all hydraulic fluid in one of the jet'stwo systems; 11 Manual extension of landing gear; 12 Loss of one generator and associatedsystems; 13 Loss of brake anti-skid system; 14 No.1 engine could not be shut down in theusual way after landing because of major damage to systems; 15 No.1 engine could not beshut down using the fire switch, which meant fire extinguishers would not work on thatengine; 16 ECAM (electronic centralised aircraft monitor) warnings about the major fuelimbalance (because of fuel leaks on left side) could not be fixed with cross-feeding; 17 Fuelwas trapped in the trim tank (in the tail) creating a balance problem for landing; 18 Left wingforward spar penetrated by debris With so much damage to the aircraft, it’s clear that all on board were extremely lucky. -

Men's 100M Diamond Discipline 03.09.2021

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 03.09.2021 Start list 100m Time: 20:23 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1Arthur CISSÉCIV9.939.9310.11WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Olympiastadion, Berlin 16.08.09 2Rohan BROWNINGAUS9.9310.0110.01AR 9.80 Lamont Marcell JACOBS ITA Olympic Stadium, Tokyo 01.08.21 3 Trayvon BROMELL USA 9.69 9.77 9.77 NR 10.02 Ronald DESRUELLES BEL Naimette-Xhovémont 11.05.85 WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene, OR 13.06.14 4 Akani SIMBINE RSA 9.84 9.84 9.84 MR 9.76 Usain BOLT JAM 16.09.11 5Fred KERLEYUSA9.699.849.84DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 6Ferdinand OMURWAKEN9.869.869.86SB 9.77 Trayvon BROMELL USA Miramar, FL 05.06.21 7 Michael NORMAN USA 9.69 9.86 8Mouhamadou FALLFRA9.8610.0810.08 2021 World Outdoor list 9.77 +1.5 Trayvon BROMELL USA Miramar, FL (USA) 05.06.21 9.80 +0.1 Lamont Marcell JACOBS ITA Olympic Stadium, Tokyo (JPN) 01.08.21 Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.83 +0.9 Bingtian SU CHN Olympic Stadium, Tokyo (JPN) 01.08.21 1Ronnie BAKER (USA) 22 9.83 +0.9 Ronnie BAKER USA Olympic Stadium, Tokyo (JPN) 01.08.21 2021 - The XXXII Olympic Games 2 Chijindu UJAH (GBR) 20 9.84 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Székesfehérvár (HUN) 06.07.21 1. Lamont Marcell JACOBS (ITA) 9.80 3André DE GRASSE (CAN) 18 9.84 +0.1 Fred KERLEY USA Olympic Stadium, Tokyo (JPN) 01.08.21 2. -

Achieving A-Grade Office Space in the Parramatta Cbd Economic Review

ACHIEVING A-GRADE OFFICE SPACE IN THE PARRAMATTA CBD ECONOMIC REVIEW 13 SEPTEMBER 2019 FINAL PREPARED FOR CITY OF PARRAMATTA URBIS STAFF RESPONSIBLE FOR THIS REPORT WERE: Director Clinton Ostwald Associate Director Alex Stuart Research Analyst Anthony Wan Project Code P0009416 Report Number Final © Urbis Pty Ltd ABN 50 105 256 228 All Rights Reserved. No material may be reproduced without prior permission. You must read the important disclaimer appearing within the body of this report. urbis.com.au CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................. i Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Planning Context................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. A Metropolis of Three Cities ................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Current Parramatta City Centre Planning Controls .............................................................................. 5 1.3. Draft Auto Alley Planning Framework (2014) ....................................................................................... 9 1.4. Parramatta City Centre Planning Framework Study (2014) .............................................................. -

Urban Design in Central Sydney 1945–2002: Laissez-Faire and Discretionary Traditions in the Accidental City John Punter

Progress in Planning 63 (2005) 11–160 www.elsevier.com/locate/pplann Urban design in central Sydney 1945–2002: Laissez-Faire and discretionary traditions in the accidental city John Punter School of City and Regional Planning, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3WA, UK Abstract This paper explores the laissez faire and discretionary traditions adopted for development control in Central Sydney over the last half century. It focuses upon the design dimension of control, and the transition from a largely design agnostic system up until 1988, to the serious pursuit of design excellence by 2000. Six eras of design/development control are identified, consistent with particular market conditions of boom and bust, and with particular political regimes at State and City levels. The constant tensions between State Government and City Council, and the interventions of state advisory committees and development agencies, Tribunals and Courts are explored as the pursuit of design quality moved from being a perceived barrier to economic growth to a pre-requisite for global competitiveness in the pursuit of international investment and tourism. These tensions have given rise to the description of Central Sydney as ‘the Accidental City’. By contrast, the objective of current policy is to consistently achieve ‘the well-mannered and iconic’ in architecture and urban design. Beginning with the regulation of building height by the State in 1912, the Council’s development approval powers have been severely curtailed by State committees and development agencies, by two suspensions of the Council, and more recently (1989) by the establishment of a joint State- Council committee to assess major development applications. -

Backpackers in Global Sydney: Final Report

Backpackers in Global Sydney Final Report Dr Fiona Allon, Australian Postdoctoral Industry Fellow, Centre for Cultural Research With Associate Professor Robyn Bushell and Professor Kay Anderson, Centre for Cultural Research And assistance from Dr Nathalie Apouchtine Centre for Cultural Research, University of Western Sydney, 2008 i About the Research Team Fiona Allon is Research Fellow at the Centre for Cultural Research, University of Western Sydney. She has published extensively in the field of Cultural Studies, and her work on backpacker tourism is well known and cited internationally. She also specialises in the analysis of contemporary Australian culture and politics, and is the author of Renovation Nation: Our Obsession with Home (2008). She researches and writes on a broad range of subjects including urban culture, suburbs, mobility and globalisation. Kay Anderson is Professor of Cultural Research at the Centre for Cultural Research, University of Western Sydney. She has a long history of intellectual engagement with issues of race and space, as signalled by her (award-winning books) Vancouver's Chinatown (1991, 2008) and Race and the Crisis of Humanism (2007), as well as publications on Aboriginal Redfern in Sydney. She has co- edited texts on the culture concept in Human Geography (Inventing Places 1991/1999; Handbook of Cultural Geography 2003), is an elected Academician of the Academy of Learned Societies for the Social Sciences (UK), and elected Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. Nathalie Apouchtine is a freelance journalist and academic researcher. Her production credits include numerous news and current* affairs specials for SBS Television, the documentary Reporting the Nation: 50 years of ABC Television News and Current Affairs (2006) and the educational CD-ROM series Making Multicultural Australia (1999). -

SYDNEY CBD OFFICE Market Overview

RESEARCH APRIL 2011 SYDNEY CBD OFFICE Market Overview HIGHLIGHTS • Many landlords took the opportunity to complete refurbishment programs on vacant buildings over 2010 in an effort to reposition the asset and boost market appeal. In contrast the majority of space coming online in 2011 and 2012 are new developments which have been underpinned by major tenant commitments and equity injections. Recent confidence about future take-up has also led to many developers/owners reigniting development pipelines in an effort to continue to grow their prime portfolios into the future. • Face rents in the CBD have stabilised, with some modest growth recorded in select assets over the past six months. Incentives have begun to contract, in particular for Premium assets and should retract sharply once tenant demand gains momentum and the excess vacant space is absorbed. Average prime gross effective rents are projected to grow by 10% per annum over the next three years, returning to their peak (mid 2008) levels by mid 2013. • Investor interest increased from late 2009 and continued throughout 2010 with $1.9 billion worth of transactions transpiring over the year to January 2011. The increased appetite from off-shore groups in 2009 and H1 2010 was followed by the return of the domestic players (including super funds, unlisted funds and private equity funds). This culminated in twelve major sales (above $10 mill) transacting since July 2010, with a total value of $1.05 billion. APRIL 2011 SYDNEY CBD OFFICE Market Overview Table 1 Sydney CBD Office Market Indicators as at January 2011 Grade Total Stock Vacancy Annual Net Annual Net Average Gross Average Average Core (m²) ^ Rate Absorption Additions Face Rent Incentive Market Yield (%) ^ (m²) ^ (m²) ^ ($/m²) (%) (%) Prime 2,368,687 7.7 73,034 98,025 650 - 950 (851 Avg) 26.5 6.50 - 7.50 (6.90 Avg) Secondary 2,475,853 8.8 32,359 18,540 450 - 560 (509 Avg) 29.0 7.75 - 8.75 (8.28 Avg) Total 4,844,540 8.2 105,392 116,565 Source: Knight Frank/PCA ^PCA OMR data as at January 2011 NB.