William Hogarth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Hogarth; His Original Engrauiljp

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ExLiBRis EvgeneAMO^h^avann JR WITHDRAWN Cornell UnlvWstty Ubrary NE 642.H71H66 William Hogarth; his original engraUilJP 3 1924 014 301 737 \ Cornell University J Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924014301737 GREAT ENGRAVERS : EDITED BY ARTHUR M. HIND PORTRAIT PE WILLIAM HOGARTH. Engraved by himself 1749 The original painting oj 1745 is in the National Gallery BOOKS OF REFERENCE (later editions Trusler, J. Hogarth moralised. London 1768 1821, 1831, ^ 1833, and 1841) Nichols, John. Biographical Anecdotes of William Hogarth, and a Catalogue of his Works (written by Nichols the publisher, George Steevens, and others). London 178 1 (later editions 1782, 1785) Ireland, John. Hogarth Illustrated. 2 vols. London 1 79 1 (later editions .,: 1793, 1798. 1806, 1 812) ' '— Samuel. Graphic Illustrations of Hogarth. 2 vols. London 1794. Cook, Thomas. Hogarth Restored. The whole works of Hogarth as originally published. Now re-engraved by T. C. Accompanied with Anecdotes . and Explanatory Descriptions. London 1802 The Works of William Hogarth, from the Original Plates restored by James Heath, to which are prefixed a Biographical Essay . ; . and Explanations of the Subjects of the Plates, by John Nichols. Printed for Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, by John Nichols & Son. London 1822. Fol. Also a later edition, printed for Baldwin and Cradock, by G. Woodfall, n.d. (1835-37 ?) WICH01.S, John Bowyer. Anecdotes of William Hogarth, written by himself, with Essays on His Life and Genius, selected from Walpole, Phillips, Gilpin, J. -

Review of the Year 2009–2010

TH E April – March NATIONAL GALLE�Y TH E NATIONAL GALLE�Y April – March Contents Introduction 5 Director s Foreword 7 Acquisitions 10 Loans 14 Conservation 18 Framing 23 Exhibitions and Display 28 Education 42 Scientific Research 46 Research and Publications 50 Private Support of the Gallery 54 Financial Information 58 National Gallery Company Ltd 60 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 62 Marble in the National Gallery 62 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2009 and March 2010, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review – The vast majority of those who visit the National message that the Gallery is a great treasure house Gallery each year come to see the permanent which they can explore for themselves, as well as collection, which is open to all and free of charge. a collection of masterpieces that are easily found. Despite being one of the greatest collections of �oom , adjacent to the Central Hall, has this Western European Old Master paintings in the year been hung with a green textile which replaces world, it tends to attract less media interest than our a damaged and discoloured yellow damask. The temporary exhibitions, perhaps for the simple reason effect on the black and silver of Goya’s Don Andrés that it is always here. It does no harm therefore to del Peral can be seen over the page. The new wall remind ourselves and others from time to time that covering also enhances the splendid Numidian our raison d’être is to care for, add to and display the marble illustrated on page and discussed at the permanent collection, to make it as widely accessible end of this volume. -

Hogarth's London Transcript

Hogarth's London Transcript Date: Monday, 8 October 2007 - 12:00AM VISUAL IMPRESSIONS OF LONDON - Hogarth's LONDON Robin Simon FSA Whatever the virtues of this country, we are not terribly good at honouring our artists. There's Gainsborough's house, there is the Watts Gallery near Guildford, and that is about it, and so how very appropriate it is that Hogarth is most famous really as the name of a roundabout! Perhaps It is a fitting measure indeed of just how urban an artist Hogarth was. His house now nestles beside one of the worst dual carriageways in Britain. It was once in the country as it is shown by an etching he made late in his life. He rests in a churchyard, St Nicholas Chiswick, that few people, alas, seem to visit. Rather oddly, it contains Whistler as well, but perhaps that is also appropriate. Hogarth's epitaph, which you can read on the very handsome tomb, was formulated by Dr Johnson, who of course remarked that he who was tired of London was tired of life, and the terms of the epitaph were finalised by their mutual friend, David Garrick, the great, possibly the greatest actor of all time, who lived off the Strand, and collected Hogarth's works. Most of those he collected can now be seen in the Sir John Soanes' Museum in Lincoln's Inn Fields. His favourite image of course, being an actor, was of himself, Hogarth's great painting of Garrick as Richard III. But he much preferred the engraving, because like any film star, he would sign copies of it, like a photograph to give away to his fans. -

John Collet (Ca

JOHN COLLET (CA. 1725-1780) A COMMERCIAL COMIC ARTIST TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I CAITLIN BLACKWELL PhD University of York Department of History of Art December 2013 ii ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the comic work of the English painter John Collet (ca. 1725- 1780), who flourished between 1760 and 1780, producing mostly mild social satires and humorous genre subjects. In his own lifetime, Collet was a celebrated painter, who was frequently described as the ‘second Hogarth.’ His works were known to a wide audience; he regularly participated in London’s public exhibitions, and more than eighty comic prints were made after his oil paintings and watercolour designs. Despite his popularity and prolific output, however, Collet has been largely neglected by modern scholars. When he is acknowledged, it is generally in the context of broader studies on graphic satire, consequently confusing his true profession as a painter and eliding his contribution to London’s nascent exhibition culture. This study aims to rescue Collet from obscurity through in-depth analysis of his mostly unfamiliar works, while also offering some explanation for his exclusion from the British art historical canon. His work will be located within both the arena of public exhibitions and the print market, and thus, for the first time, equal attention will be paid to the extant paintings, as well as the reproductive prints. The thesis will be organised into a succession of close readings of Collet’s work, with each chapter focusing on a few representative examples of a significant strand of imagery. These images will be examined from art-historical and socio-historical perspectives, thereby demonstrating the artist’s engagement with both established pictorial traditions, and ephemeral and topical social preoccupations. -

Hogarth 2 18/05/2021 15:38 Hogarth

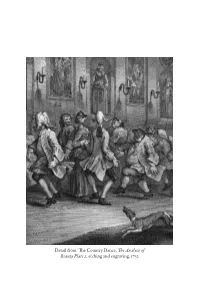

Detail from ‘The Country Dance’,The Analysis of Beauty Plate 2, etching and engraving, 1753 Hogarth 2 18/05/2021 15:38 HOGARTH Life in Progress JACQUELINE RIDING PROFILE BOOKS Hogarth 3 18/05/2021 15:38 First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Profile Books Ltd 29 Cloth Fair London ec1a 7jq www.profilebooks.co.uk Copyright © Jacqueline Riding, 2021 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 78816 347 7 eISBN 978 1 78283 611 7 Hogarth 6 18/05/2021 15:38 Contents Prologue 1 Interlude One 12 1 Good Child 31 Interlude Two 71 2 Mock King 82 Interlude Three 121 3 Moral Subject 136 Interlude Four 177 4 History Maker 188 Interlude Five 214 5 Feeling Fellow 223 Interlude Six 247 6 Nature’s Dramatist 264 Interlude Seven 304 7 True Patriot 313 Interlude Eight 363 8 Original Genius 380 Epilogue 443 Notes 447 Bibliography 484 List of Illustrations 498 Acknowledgements 504 Index 507 Hogarth 9 18/05/2021 15:38 PROLOGUE ‘Wond’ring Muse’* From deep within the infinite realm, tentative light beams pulse and flicker, hinting at unnumbered stars, of untold planets. -

Crime, Deviance, and the Social Discovery of Moral Panic In

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES History Volume 1 of 1 Crime, Deviance, and the Social Discovery of Moral Panic in Eighteenth Century London, 1712-1790 by Christopher Thomas Hamerton Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis utilises the theoretical device of Folk Devils and Moral Panics, instigated by Stanley Cohen and developed by Erich Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda, to explore the discovery of, and social response to, crime and deviance in eighteenth- century London. The thesis argues that London and its media in the eighteenth- century can be identified as the initiating historical site for what might now be termed public order moral panics. The scholarly foundation for this hypothesis is provided by two extensively researched chapters which evaluate and contextualise the historiography of public opinion and media alongside the unique character and power located within the burgeoning metropolis. This foundation is followed by a trio of supportive case studies, which examine and inform on novel historical episodes of social deviance and criminality. These episodes are selected to replicate a sequence of observable folk devils within Cohen’s original typology – youth violence, substance abuse, and predatory sex offending. Which are transposed historically as the Mohocks in 1712, Madam Geneva between 1720-1751, and the London Monster in 1790. Taken together, these three episodes provide historical lineage of moral panic which traverses much of the eighteenth-century, allowing for social change, and points of convergence and divergence, to be observed. Furthermore, these discrete episodes of moral panic are used to reveal the social problems of the eighteenth-century capital that informed the control narratives that followed. -

Catalogue of the Concluding Part of the Extensive Collection of Prints

■fcv^jVt.- I \ m r: \ i1 1 I I 1 i CATALOGUE OF THE CONCLUDING PART OF THE EXTENSIVE COLLECTION OF PRINTS, rORMED BY GENERAL DOWDESWELL ; WHICH COMPRISES INNUMERABLE SPECIMENS OF THE ENGRAVER’S ARTj, from the dawn of its exercise in 1450, to the end of the 18th Century, A CONSIDERABLE PORTION OF THE WQIIKS OF WENCESLAUS HOLLAR^ ESPECIALLY IN PORTRAITS AND VIEWS; A valuable COLLECTION OF BRITISH PORTRAITS, including many by Passe, Hogenbekg, Faithohne, &c. of extreme rarity, and of Vertue, nearly complete; AN extensive COLLECTION OF CARICATURES BY GILLRAY, SAYERS, &c. AN INTERESTING COLLECTION OF BRITISH TOPOGRAPHY, including an Extensive & Valuable Selection to Illustrate Pennant's History of London, Manning and Bray’s SuaREY, &c. &c. AND A CHOICE COLECTION OF SUPERIOR ENGRAVINGS, from the best formed Galleries of Art throughout Europe, cojpprising the Finest Productions of the most effective Engravers of recent date, in curious Proofs, &c. &c. the whole collected to Illustrate Pilkington’s Dictionary of Painters, and Dodd’s Universal History of Artists, WHICH WILL BE ^ SOLD BY AUCTION, BY MR. EVANS^ AT HIS HOUSE, No. 93, PALL MALL, On Tuesday, November 11, and Four following Days, 1828. CONDITIONS OF SALE. I. The highest Bidder to be the Buyer; and if any Dispute arises between two or more Biddersj the Lot so disputed, shall be immediately put up again and re-sold. n. No Person to advance less than Is.; above Five Pounds, •is. 6d. 5 and so in Proportion. III. The Purchasers to give in their Names and^Places of Abode, and to pay down 5s. -

Hogarth His Life and Society

• The 18th century was the great age for satire and caricature. • Hogarth • Gillray, Rowlandson, Cruikshank 1 2 Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), grotesque faces, c. 1492 Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), grotesque heads, 1590 Annibale Carracci, The Bean Eater, 1580-90, 57 × 68 cm, Galleria Colonna, Rome • Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) drew some of the earliest examples of caricature (exaggeration of the physical features of a face or body) but they do not have a satirical intent. These faces by Leonardo are exploring the limits of human physiognomy. • The Italian artist Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) was know for and was one of the first artists in Italy to explore the appearance of everyday life. Here are some heads he sketched and a well-known painting called The Bean Eater. He is in the middle of a simple meal of beans, bread, and pig's feet. He is not shown as a caricature or as a comical or lewd figure but as a working man with clean clothes. The ‘snapshot’ effect is entirely unprecedented in Western art and he shows dirt under the fingernails before Caravaggio. Food suitable for peasants was considered to be dark and to grow close to the ground. Aristocrats would only least light coloured food that grew a long way from the ground. It is assumed that this painting was not commissioned but was painted as an exercise. The painting owes much to similar genre painting in Flanders and Holland but in Italy it was unprecedented for its naturalism and careful, objective study from life. • The Carracci were a Bolognese family that helped introduce the Baroque. -

William Hogarth Images, Engraved by Riepenhausen) PF EC7.H6786.750F Finding Aid Prepared by Ellen Williams

Sammlung Hogarthischer Kupferstiche (William Hogarth images, engraved by Riepenhausen) PF EC7.H6786.750f Finding aid prepared by Ellen Williams. Last updated on July 14, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2012 Sammlung Hogarthischer Kupferstiche (William Hogarth images, engraved by Riepenhausen) Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Volume 1..................................................................................................................................................8 -

“Absalom and Achitophel” (Dryden), 170 Academy of Ancient Music, 157

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89652-8 - London: A Social and Cultural History, 1550–1750 Robert O. Bucholz and Joseph P. Ward Index More information Index “Absalom and Achitophel” (Dryden), 170 Anglican Chapel Royal, 113 Academy of Ancient Music, 157 Anglican Church, 147–148 Ackroyd, Peter, 27 Anglicans, civic government and, 125, Act against Seditious Words and Rumours 127 Uttered against the Queen’s Most Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 15 Excellent Majesty 1581, 167 Anglo-Saxons, settlement in London, Act for Keeping Children Alive 1767, 238 14–15 Act for Rebuilding the City of London Anne, Queen, 26 1667, 327 birthday celebration, fashion and, 111 Act of Settlements and Removals 1662, 229 as conversationalist, 115 Addison, Joseph, 30, 90, 180–185, 197, renovations of, 136–137 199 residence of court, 103 Advent, 211 anomie, 71 advertisements, in newspapers, 174–179 Apollo Club, 198 Aethelberht, King, 14 The Apotheosis of James I (Rubens), 138 agricultural laborers, 68 apprentices, 79–80 The Alchemist (Jonson), 142 approach, to London, aldermen, 123–125, 127, 254 from east, by water, 334–336 alehouses, 192–194 from east and south, 35–38 Alfred, King, 15 from west and north, 33–35 Ailesbury, Thomas Bruce, second Earl of, Arbuthnot, John, 197–198, 366 302 Archer, Ian, 278 All Hallows Bread Street, 286 archery, 204 All Saint’s Day, 211 architecture All Soul’s Day, 210–211 1660–1750, 148 Allen, Thomas, 112 rebuilding after Great Fire of 1666, All-Hallow’s Eve, 209, 211 328–331 Alsatia, 53, 246 Arden of Feversham (Anonymous), 243 Anchor Brewery, 193 Areopagitica (Milton), 146–147 393 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89652-8 - London: A Social and Cultural History, 1550–1750 Robert O. -

William Hogarth: the Analysis of Beauty (1753)

„To see with our own eyes“: HOGARTH BETWEEN NATIVE EMPIRICISM AND A THEORY OF ‘BEAUTY IN FORM’ WILLIAM HOGARTH: The Analysis of Beauty (London: Printed by John Reeves for the Author, 1753) edited with an Introduction by CHARLES DAVIS FONTES 52 [20 July 2010] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2010/1217/ urn:nbn:de:16-artdok-12176 1 T H E A N A L Y S I S O F B E A U T Y. Written with a view of fixing the fluctuating I D E A S of T A S T E. ___________________________________________ B Y W I L L I A M H O G A R T H. ___________________________________________ So vary’d he, and of his tortuous train Curl’d many a wanton wreath, in sight of Eve, To lure her eye. -------- Milton. ___________________________________________ VARIETY ≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡ L O N D O N : Printed by J. R E E V E S for the A U T H O R, And Sold by him at his House in LEICESTER-FIELDS. ______________________ MDCCLIII. FONTES 52 (Hogarth 1) 2 3 C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION: 4 “To see with our own eyes”: HOGARTH BETWEEN NATIVE EMPIRICISM AND A THEORY OF ‘BEAUTY IN FORM’ THE FULL TEXT OF THE ANALYSIS OF BEAUTY 18 NOTE TO THE TEXT 122 THE ANALYSIS: EDITIONS AND TRANSLATIONS 123 WILLIAM HOGARTH – BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE 129 LITERATURE ABOUT HOGARTH 131 ILLUSTRATIONS 132 4 INTRODUCTION: “To see with our own eyes”: HOGARTH BETWEEN NATIVE EMPIRICISM AND A THEORY OF ‘BEAUTY IN FORM’ by Charles Davis Although the word ‘taste’ figures in the title of Hogarth’s book, the work is centrally concerned with demonstrating the sources of beauty – why objects are beautiful. -

Freemasonry and the Civil War: a House Undivided by Justin Lowe [From

FREEMASONRY AND SOCIAL ENGLAND IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY by Wor. Bro. GILBERT W. DAYNES The subject I have selected for my Paper this evening is one concerning which little or no attention has apparently been paid by students. Many books have been written in which the social conditions existing in England in the 18th century have been passed under review, and we have also Histories of Freemasonry in England during the same period, but in neither case has any serious attempt been made to connect the widespread growth and universality of the latter with any of the improved conditions of the former. It is, I fear, quite impossible in the time at my disposal to analyse with any considerable detail the various facts concerning Freemasonry, which may have affected the social life of England as a whole ; but I will endeavour to set before you, in as brief a manner as possible, the principles and tenets inculcated in Freemasonry from the early part of the 18th century, and indicate broadly the lines upon which further investigation might be undertaken, with the view of ascertaining, if possible, the effect of these teachings of Freemasonry upon the social conditions then existing. From the 13th century, and probably even earlier, Masons, when congregated together, appear to have met in Lodges - then the workroom attached to the building in progress. At the beginning of the 18th century only a few such groups remained, such as those at Alnwick and Swalwell - then meeting in taverns - whose records survive to show that they existed for the operative purpose of regulating the Masons' trade.