William Hogarth; His Original Engrauiljp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hogarth in British North America

PRESENCE IN PRINT: WILLIAM HOGARTH IN BRITISH NORTH AMERICA by Colleen M. Terry A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Summer 2014 © 2014 Colleen Terry All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 3642363 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3642363 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 PRESENCE IN PRINT: WILLIAM HOGARTH IN BRITISH NORTH AMERICA by Colleen M. Terry Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Lawrence Nees, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Art History Approved: ___________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences Approved: ___________________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ___________________________________________________________ Bernard L. Herman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Issues) and Begin with the Summer Issue

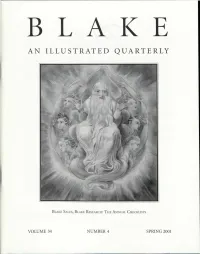

AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY BLAKE SALES, BLAKE RESEARCH: THE ANNUAL CHECKLISTS VOLUME 34 NUMBER 4 SPRING 2001 £%Uae AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY VOLUME 34 NUMBER 4 SPRING 2001 CONTENTS Articles Newsletter Blake in the Marketplace, 2000 Met Exhibition Through June, Blake Society Lectures, by Robert N. Essick 100 The Erdman Papers 159 William Blake and His Circle: A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2000 By G. E. Bentley, Jr., with the Assistance of Keiko Aoyama for Japanese Publications 129 ADVISORY BOARD G. E. Bentley, Jr., University of Toronto, retired Nelson Hilton, University of Georgia Martin Butlin, London Anne K. Mellor, University of California, Los Angeles Detlef W. Dbrrbecker, University of Trier Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Robert N. Essick, University of California, Riverside David Worrall, St. Mary's College Angela Esterhammer, University of Western Ontario CONTRIBUTORS SUBSCRIPTIONS are $60 for institutions, $30 for individuals. All subscriptions are by the volume (1 year, 4 issues) and begin with the summer issue. Subscription payments re• G. E. BENTLEY, JR. has just completed The Stranger from ceived after the summer issue will be applied to the 4 issues Paradise in the Belly of the Beast: A Biography of William of the current volume. Foreign addresses (except Canada Blake. and Mexico) require a $10 per volume postal surcharge for surface, and $25 per volume surcharge for air mail delivery. ROBERT N. ESSICK is Professor of English at the University U.S. currency or international money order necessary. Make of California, Riverside. checks payable to Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly. Address all subscription orders and related communications to Sarah Jones, Blake, Department of English, University of Roches• ter, Rochester, NY 14627. -

Catalogue of the Splendid Collection of Pictures

CATALOGUE OP THE SPLENDID COLLECTION OF PICTURES BELONGING TO PRINCE LUCIEN BUONAPARTE; WHICH WILL BE EXHIBITED FOR SALE BY PRIVATE CONTRACT, ON MONDAY THE SIXTH DAY OF FEBRUARY, 1815, AND FOLLOWING DAYS, AT THE NEW GALLERY, (MR. BUCHANAN’S) No. 60, PALL-MALL. ADJOINING THE BRITISH GALLERY". % Admittance One Shilling.— Descriptive Catalogue Eighteen-pence, .In England, where there is no National Gallery for the reception of the chefs-d’oeuvre of the Great Mas¬ ters of the various schools, where the amateur or the student might at all times have an opportunity of improving his taste, or forming his. knowledge on works of art, every thing must naturally be considered as desirable, which can in any degree tend to afford facility for such study, or acquirements. The numerous applications which have been made to view the Collection of Pictures belonging to Prince •Lucien Buonaparte have induced those under whose direction it has been placed, to open the New Gallery, in Pall-Mall, to the Public, in the manner usually adopted in this country : they have also resolved to allow the Collection itself to he separated, and sold, in the same manner as the celebrated Collection of the Duke of Orleans; being convinced that Collectors will feel more satisfied in having an opportunity afforded them of gratifying their wishes individually, by a selection of such pictures as may suit the taste of each purchaser. 2 This Collection has been formed from many of the principal Cabinets on the Continent, during a period of the last fifteen years; and not only has the greatest attention been paid to a selection of agreeable subjects of the different masters, but also to the quality and state of preservation of the pictures themselves. -

The Life, Studies, and Works of Benjamin West, Esq., by John Galt, in Extra-Illustrated Form 3239 Finding Aid Prepared by Cary Majewicz

The Life, Studies, and Works of Benjamin West, Esq., by John Galt, in extra-illustrated form 3239 Finding aid prepared by Cary Majewicz. Last updated on November 09, 2018. First edition Historical Society of Pennsylvania , 2010 The Life, Studies, and Works of Benjamin West, Esq., by John Galt, in extra-illustrated form Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Inventory of original art and large-scale engravings in Collection 3239......................................................6 Administrative Information......................................................................................................................... 11 Related Materials......................................................................................................................................... 12 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................12 Bibliography.................................................................................................................................................13 - Page 2 - -

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Prints from the Collection of the Hon. Christopher Lennox-Boyd Arts 3801 [Little Fatima.] [Painted by Frederick, Lord Leighton.] Gerald 2566 Robinson Crusoe Reading the Bible to Robinson. London Published December 15th 1898 by his Man Friday. "During the long timer Arthur Lucas the Proprietor, 31 New Bond Street, W. Mezzotint, proof signed by the engraver, ltd to 275. that Friday had now been with me, and 310 x 490mm. £420 that he began to speak to me, and 'Little Fatima' has an added interest because of its understand me. I was not wanting to lay a Orientalism. Leighton first showed an Oriental subject, foundation of religious knowledge in his a `Reminiscence of Algiers' at the Society of British mind _ He listened with great attention." Artists in 1858. Ten years later, in 1868, he made a Painted by Alexr. Fraser. Engraved by Charles G. journey to Egypt and in the autumn of 1873 he worked Lewis. London, Published Octr. 15, 1836 by Henry in Damascus where he made many studies and where Graves & Co., Printsellers to the King, 6 Pall Mall. he probably gained the inspiration for the present work. vignette of a shipwreck in margin below image. Gerald Philip Robinson (printmaker; 1858 - Mixed-method, mezzotint with remarques showing the 1942)Mostly declared pirnts PSA. wreck of his ship. 640 x 515mm. Tears in bottom Printsellers:Vol.II: margins affecting the plate mark. -

Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 a Dissertation Submitted in Part

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Sentiment and Laughter: Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Leigh-Michil George 2016 © Copyright by Leigh-Michil George 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Sentiment and Laughter: Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 by Leigh-Michil George Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Jonathan Hamilton Grossman, Co-Chair Professor Felicity A. Nussbaum, Co-Chair This dissertation examines how late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century British novelists—major authors, Laurence Sterne and Jane Austen, and lesser-known writers, Pierce Egan, Charles Jenner, and Alexander Bicknell—challenged Henry Fielding’s mid-eighteenth-century critique of caricature as unrealistic and un-novelistic. In this study, I argue that Sterne, Austen, Egan, and others translated visual tropes of caricature into literary form in order to make their comic writings appear more “realistic.” In doing so, these authors not only bridged the character-caricature divide, but a visual- verbal divide as well. As I demonstrate, the desire to connect caricature with character, and the visual with the verbal, grew out of larger ethical and aesthetic concerns regarding the relationship between laughter, sensibility, and novelistic form. ii This study begins with Fielding’s Joseph Andrews (1742) and its antagonistic stance towards caricature and the laughter it evokes, a laughter that both Fielding and William Hogarth portray as detrimental to the knowledge of character and sensibility. My second chapter looks at how, increasingly, in the late eighteenth century tears and laughter were integrated into the sentimental experience. -

Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy and the Aesthetic Theory And

LAURENCE STERNE"S TRISTRAM SHANDY AND THE AESTHETIC THEORY AND PRACTISE OF WILLIAM HOGARTH BY NANCY A. WALSH. B.A. AThesis Submitted to the School of OraduateStudies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Mester of Arts McMester University September 1986 MASTER OF ARTS ( 1986) McMASTER UNIVERSITY ( English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Laurence Sterne's Tristram ShanW and the Aesthetic Theory and Practise of William Hogarth AUTHOR: NanL)' A. Walsh, B. A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. James King NUMBER OF PAGES: vi; 77 ., II ABSTRACT Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy in many wetys follows the same aesthetic principles that English painter William Hogarth displetys in his work and discusses in his treatise The Analysis of Beauty. The affinities between Hogarth's and Sterne's aesthetic methooalogies have been noted--but not subjected to close examination--by modern scholars. This thesis explores some of the slmllarltles between the two men: their rejection of neoclassical convention, their attempts to transcend the boundaries of their respective mediums, their ultimate recognition of the intrinsic differences between literature and art and of the limitations and advantages peculiar to each, and their espousal of rococo values: Hogarth in his moral progresses and In his Analysis of Beauty, and Sterne in the narrative structure of Tristram Shandy. Sterne acquired from Hogarth illustrations to Tristram Shancty, confesses his admiration for the painter's method of characterization, and commended and borrowed freely from his Analysis. This evidence strongly suggests (but cannot conclusively prove) that Hogarth influenced Sterne's narrative methodology in Tristram Shancty. Even if Sterne did not consciously and deliberately incorporate Hogarth's aesthetic prinCiples into his novel, the many analogies between the techniques used by the two men reveal much about the general aesthetic movement taking place in the eighteenth-century; a movement in which they pletyed an important part. -

Dairy Culture: Industry, Nature and Liminality in the Eighteenth- Century English Ornamental Dairy

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-02-01 Dairy Culture: Industry, Nature and Liminality in the Eighteenth- Century English Ornamental Dairy Ashlee Whitaker Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Whitaker, Ashlee, "Dairy Culture: Industry, Nature and Liminality in the Eighteenth-Century English Ornamental Dairy" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1327. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1327 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DAIRY CULTURE: INDUSTRY, NATURE AND LIMINALITY IN THE EIGHTEENTH- CENTURY ENGLISH ORNAMENTAL DAIRY by Ashlee Whitaker A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Visual Arts Brigham Young University April 2008 Copyright © 2008 Ashlee Whitaker All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT DAIRY CULTURE: INDUSTRY, NATURE AND LIMINALITY IN THE EIGHTEENTH- CENTURY ENGLISH ORNAMENTAL DAIRY Ashlee Whitaker Department of Visual Arts Master of Arts The vogue for installing dairies, often termed “fancy” or “polite” dairies, within the gardens of wealthy English estates arose during the latter half of the eighteenth century. These polite dairies were functional spaces in which aristocratic women engaged, to varying degrees, in bucolic tasks of skimming milk, churning and molding butter, and preparing crèmes. As dairy work became a mode of genteel activity, dairies were constructed and renovated in the stylish architectural modes of the day and expanded to serve as spaces of leisure and recreation. -

William Hogarth: British Satirical Prints

Works in the Exhibition William Hogarth: British Satirical Prints 1. Hudibras Encounters the Skimmington (Plate VII) from the series 10. The Battle of the Pictures, 1745 16. The Reward of Cruelty (Plate IV) from The Four Stages of Cruelty See John the soldier, Jack the Tar, with Sword & Pistol arm'd for War, should February 7 — April 13, 2008 Large Illustrations for Samuel Butler’s Hudibras, 1725-26 Thomas Cook, After William Hogarth 1750-51 Mounsir dare come here ! - The Hungry Slaves have smelt our Food, they Thomas Cook, After William Hogarth Etching, 9 x 9 11/16 in. Thomas Cook, After William Hogarth long to taste our Flesh and Blood, Old England's Beef and Beer! - Britons to Arms! and let 'em come, Be you but Britons still, Strike Home, And Lion-like (published by George and John Robinson, 1802) Anonymous Gift, 00.212 (published by George, George and John Robinson, 1799) attack 'em; - No Power can stand the deadly Stroke, That's given from hands Engraving, 13 3/8 x 21 3/8 in. Etching and engraving, 18 7/8 x 15 3/8 in. The Bearer hereof is Entitled (if he thinks proper) to be a Bidder for Mr. & hearts of Oak, With Liberty to back em. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Leslie S. Pinsof, 00.147 Hogarth’s Pictures which are to be Sold on the Last day of this Month. Anonymous Gift, 00.138 This said, they both advanc'd and rode A Dog Trot through the bawling Behold the Villain’s dire disgrace! Not Death itself can end. -

John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Promotion of a National Aesthetic

JOHN BOYDELL'S SHAKESPEARE GALLERY AND THE PROMOTION OF A NATIONAL AESTHETIC ROSEMARIE DIAS TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2003 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Volume I Abstract 3 List of Illustrations 4 Introduction 11 I Creating a Space for English Art 30 II Reynolds, Boydell and Northcote: Negotiating the Ideology 85 of the English Aesthetic. III "The Shakespeare of the Canvas": Fuseli and the 154 Construction of English Artistic Genius IV "Another Hogarth is Known": Robert Smirke's Seven Ages 203 of Man and the Construction of the English School V Pall Mall and Beyond: The Reception and Consumption of 244 Boydell's Shakespeare after 1793 290 Conclusion Bibliography 293 Volume II Illustrations 3 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a new analysis of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, an exhibition venture operating in London between 1789 and 1805. It explores a number of trajectories embarked upon by Boydell and his artists in their collective attempt to promote an English aesthetic. It broadly argues that the Shakespeare Gallery offered an antidote to a variety of perceived problems which had emerged at the Royal Academy over the previous twenty years, defining itself against Academic theory and practice. Identifying and examining the cluster of spatial, ideological and aesthetic concerns which characterised the Shakespeare Gallery, my research suggests that the Gallery promoted a vision for a national art form which corresponded to contemporary senses of English cultural and political identity, and takes issue with current art-historical perceptions about the 'failure' of Boydell's scheme. The introduction maps out some of the existing scholarship in this area and exposes the gaps which art historians have previously left in our understanding of the Shakespeare Gallery. -

Commemorating the Anniversary Of

MUSIC & READINGS THE PERFORMERS G F Handel (1685-1759) Rosalind Knight is an actor; she is a trustee of the William Hogarth Trust and led ‘Overture’ from Judas Maccabeus the fund-raising to re-instate David Garrick’s urns on the Hogarth’s House gate-posts. Lars Tharp is Hogarth Curator of the Foundling Museum. A ceramics historian and Hogarth’s early life readings by Rosalind Knight broadcaster, he was lured into William Hogarth’s interiors by a profusion of ‘pots’. J C Pepusch (1667-1752) & John Gay (1685-1732) James Wisdom is Chairman of the Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society and ‘Over the Hills and Far Away’ from The Beggar’s Opera works with a number of local heritage organisations W Boyce (1711-1779) Ars Eloquentiae was formed in 2012; it is a versatile ensemble with a wide- Symphony No 1 in B flat major ranging repertoire in period performance. Its members are young professional Mellon British Art Collection, B1981.25.360 for Paul Centre Yale i Allegro musicians, who also individually perform with many highly-renowned early ii Moderato e dolce music ensembles. They enjoy a residency and sponsorship from St Anne’s, Kew iii Allegro Green where they have gained a loyal following over the last 3 years. During 2014 Ars Eloquentiae has been working with the University of Cambridge, Hogarth & Music readings by Rosalind Knight researching and recording Parisian street songs from the 17th Century. Forthcoming engagements in 2014 include a concert at the Wimbledon G F Handel (1685-1759) & Thomas Morell (1703-1784) International Music Festival, a Winter Season at St. -

A Review of William Hogarth's Marriage À La Mode with Particular

A Review of William Hogarth's Marriage ~ la Mode -with Particular Reference to Character and Setting by Robert L. S. Cowley VOLUME· I THE THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Dootor of Philosophy of the University of Birmingham Shakespeare Institute May, 1977 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ANY IMAGES MISSING FROM THIS DIGITAL COpy HAVE BEEN EXCLUDED AT THE REQUEST OF THE UNIVERSITY SYNOPSIS The thesis has been prepared on the assumption that Hogarth's pioture series are essentially narrative works. They are oonsidered in the Introduotion in the light of reoent definitions of the narrative strip, a medium in whioh Hogarth was a oonsiderable innovator. The first six ~hapters oonsist of an analysis of each of the pic- tures in Marriage ~ la Mode. The analysis was undertaken as a means of exploring the nature of Hogarth's imagination and to disoover how ooherent a work the series is. There is an emphasis on oharaoterization and setting because Hogarth himself chose to isolate character as a feature in the subscription ticket to Marriage ~ la Mode.