Stop and Go Nodes of Transformation and Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1957 – the Year the Space Age Began Conditions in 1957

1957 – The Year the Space Age Began Roger L. Easton, retired Naval Research Laboratory Linda Hall Library Kansas City MO 6 September 2007 Conditions in 1957 z Much different from now, slower, more optimistic in some ways z Simpler, yet very frightening, time 1 1957 in Politics z January 20: Second Presidential Inauguration of Dwight Eisenhower 1957 in Toys z First “Frisbee” from Wham-O 2 1957 in Sports z Third Year of Major League Baseball in Kansas City z the “Athletics,” not the “Royals” 1957 in Sports z No pro football in Kansas City z AFL was three years in future z no Chiefs until 1963 3 1957 at Home z No microwave ovens z (TV dinners since 1954) z Few color television sets z (first broadcasts late in 1953) z No postal Zip Codes z Circular phone diales z No cell phones z (heck, no Area Codes, no direct long-distance dialing!) z No Internet, no personal computers z Music recorded on vinyl discs, not compact or computer disks 1957 in Transportation z Gas cost 27¢ per gallon z September 4: Introduction of the Edsel by Ford Motor Company z cancelled in 1959 after loss of $250M 4 1957 in Transportation z October 28: rollout of first production Boeing 707 1957 in Science z International Geophysical Year (IGY) z (actually, “year and a half”) 5 IGY Accomplishments z South Polar Stations established z Operation Deep Freeze z Discovery of mid-ocean submarine ridges z evidence of plate tectonics z USSR and USA pledged to launch artificial satellites (“man-made moons”) z discovery of Van Allen radiation belts 1957: “First” Year of Space Age z Space Age arguably began in 1955 z President Eisenhower announced that USA would launch small unmanned earth-orbiting satellite as part of IGY z Project Vanguard 6 Our Story: z The battle to determine who would launch the first artificial satellite: z Werner von Braun of the U.S. -

NIMEINDEKS Nimeindeksi Toimetaja: Leida Lepik Korrektuur: Eva-Leena Sepp

Tallinna ühistranspordi kaardi NIMEINDEKS Nimeindeksi toimetaja: Leida Lepik korrektuur: Eva-Leena Sepp ©REGIO 1997 Tähe 118, TARTU EE2400 tel: 27 476 343 faks: 476 353 [email protected] http://www.regio.ee Müük*Sale: Kastani 16, TARTU EE2400 tel: 27 420 003, faks: 27 420199 Laki 25, TALLINN EE0006 tel: 25 651 504, faks: 26 505 581 NB! (pts) = peatus/stop/pysäki/остановка A Asfalt-betoonitehas (pts) J4 ENDLA Adamsoni E4, F4, J7, K7 ASTANGU C6 E5, F4-5, H8,18, J8, K8 A.Adamsoni (pts) F4, J7, K7 Astangu B6, C6 Endla H6 A.AIIe G4 Astangu (pts) B6, C6 Endla (pts) J8 Aarde E4,16,17 Astla tee J2 Energia E6 Aasa F5, J8 Astri E7 Energia (pts) E6 Aasnurmika tee L2 Astri (pts) E7 Erika E3,15 Aate D7, E7 Astri tee 11 Erika (pts) E3 Aaviku J1 Asula F5 Estonian Exhibitions H4 Abaja J3 Asunduse G4, H4 "Estonia" (pts) F4, L7 Aedvilja M7 Asunduse (pts) FI4 ESTONIA PST F4 Aegna pst J3 Auli E5 F Ahju F5, L8 Auna E4, H6,16 Falgi tee F4, K7 Ahtri F4, G4, M6-7 Auru F5 Farm (pts) G2 Ahvena tee A4 Auru (pts) F5 Filmi G4 Äia F4, L6, L7 Auru põik F5 Filtri tee G5, N8 Aiandi 11 Auto C8 Flower Pavilion H4 Aiandi (pts) D5 Autobussijaam G5, N8 Forelli D5 Aianduse tee J1-2 Autobussijaam (pts) G4 Forelli (pts) D5 Aianduse tee (pts) J2 Autobussikoondis (pts) Fosforiidi N3 Aiaotsa L1 C5, D5 F.R.Faehlmanni G4, N7 Aiaotsa (pts) H2, L1,K2 В F. R.Kreutzwaldi G4, M8, N7 Aiatee I2 Balti jaam F4, K6 G Äia tee (pts) I2 Balti jaam (pts) F4 Gaasi J4 Aida L6 BEKKERI D3 Gaasi (pts) I4, J4 Airport H5 Bekkeri sadam D3 Gildi G4-5, N8 AKADEEMIA TEE C6, D6 Bensiini G4 Glehn! D6, E6 Akadeemia tee (pts) C6, D6 Betooni I4-5, J5 Glehn! park C7 Alajaama E6 Betooni (pts) I5 GONSIORI G4, M7, N7 Alasi D3 Betooni põik J5 Gonsiori G4 Aiesauna L2 Betooni põik (pts) J5 G. -

Key Officers List

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 5/24/2017 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan GSO Jay Thompson RSO Jan Hiemstra AID Catherine Johnson KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, CLO Kimberly Augsburger Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: ECON Jeffrey Bowan kabul.usembassy.gov EEO Daniel Koski FMO David Hilburg Officer Name IMO Meredith Hiemstra DCM OMS vacant IPO Terrence Andrews AMB OMS Alma Pratt ISO Darrin Erwin Co-CLO Hope Williams ISSO Darrin Erwin DCM/CHG Dennis W. Hearne FM Paul Schaefer HRO Dawn Scott Algeria INL John McNamara MGT Robert Needham ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- MLO/ODC COL John Beattie 2000, Fax +213 (21) 60-7335, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, POL/MIL John C. Taylor Website: http://algiers.usembassy.gov SDO/DATT COL Christian Griggs Officer Name TREAS Tazeem Pasha DCM OMS Susan Hinton US REP OMS Jennifer Clemente AMB OMS Carolyn Murphy AMB P. Michael McKinley Co-CLO Julie Baldwin CG Jeffrey Lodinsky FCS Nathan Seifert DCM vacant FM James Alden PAO Terry Davidson HRO Carole Manley GSO William McClure ICITAP Darrel Hart RSO Carlos Matus MGT Kim D'Auria-Vazira AFSA Pending MLO/ODC MAJ Steve Alverson AID Herbie Smith OPDAT Robert Huie CLO Anita Kainth POL/ECON Junaid Jay Munir DEA Craig M. Wiles POL/MIL Eric Plues ECON Dan Froats POSHO James Alden FMO James Martin SDO/DATT COL William Rowell IMO John (Troy) Conway AMB Joan Polaschik IPO Chris Gilbertson CON Stuart Denyer ISO Wally Wallooppillai DCM Lawrence Randolph POL Kimberly Krhounek PAO Ana Escrogima GSO Dwayne McDavid Albania RSO Michael Vannett AGR Charles Rush TIRANA (E) 103 Rruga Elbasanit, 355-4-224-7285, Fax (355) (4) 223 CLO Vacant -2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm, Website: EEO Jake Nelson http://tirana.usembassy.gov/ FMO Rumman Dastgir IMO Mark R. -

Reference List for Ferries

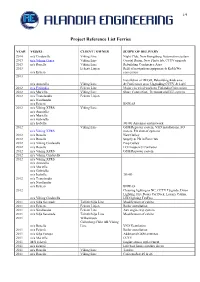

1/4 Project Reference List Ferries YEAR VESSEL CLIENT / OWNER SCOPE OF DELIVERY 2014 m/s Cinderella Viking Line Night Club, New Kongsberg Automation system 2013 m/s Viking Grace Viking Line Coastal Roam, New Photo lab, CCTV upgrade 2013 m/s Rosella Viking Line Rebuilding Conference Area 2013 Eckerö Linjen Refit of navigation equipment & KaMeWa m/s Eckerö conversion 2013 Installation of DEGO, Rebuilding Kids area m/s Amorella Viking Line & Conference area. Upgrading CCTV & LAN 2012 m/s Finlandia Eckerö Line Major electrical works to Finlandia Conversion 2012 m/s Mariella Viking Line Shore Connection, Demount old LLL system 2012 m/s Translandia Eckerö Linjen m/s Nordlandia m/s Eckerö BNWAS 2012 m/s Viking XPRS Viking Line m/s Amorella m/s Mariella m/s Gabriella m/s Isabella 3G/4G Antennas and network 2012 Viking Line GSM Repeater system, VSD installations, FO m/s Viking XPRS meters, FO shut-of systems 2012 m/s Rosella New Galley 2012 m/s Rosella Supply & PB in Fun Club 2012 m/s Viking Cinderella Prep Galley 2012 m/s Rosella LO Frequency Converter 2012 m/s Viking XPRS GSM Repeater system 2012 m/s Viking Cinderella 2012 m/s Viking XPRS m/s Amorella m/s Mariella m/s Gabriella m/s Isabella 3G/4G 2012 m/s Translandia m/s Nordlandia m/s Eckerö BNWAS 2012 Cleaning lighting in NC, CCTV Upgrade, Disco Lighting, Fire Doors Car Deck, Luxury Cabins, m/s Viking Cinderella LED lighting TaxFree 2011 m/s Silja Serenade Tallink/Silja Line Modification of cabins 2011 m/s Eckerö Eckerö Linjen Boiler installation 2011 m/s Nordlandia Eckerö Line Aux engine -

Telephone Directory

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 4/27/2015 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan CG OMS Shawn White MGT David McCrane PO Peter G. Kaestner KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, POL Matthew Lowe Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: kabul.usembassy.gov Albania Officer Name DCM OMS Roland Elliott TIRANA (E) 103 Rruga Elbasanit, 355-4-224-7285, Fax (355) (4) 223 AMB OMS Alma Pratt -2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-5:00pm, Website: Co-CLO Margaret Lorinser http://tirana.usembassy.gov/ DHS/CBP Gregory Wilbur Officer Name ECON/COM Walter Koenig DCM OMS Erne Guzman FM Keith Hanigan AMB OMS Elizabeth Soderholm HRO Rosario (Cherry) Larsen FM Paul Bottse INL Chris Sandrolini HRO Craig Kennedy MGT Gregory Stanford ICITAP Steve Bennett POL/MIL Bertram Braun MGT John K. Madden SDO/DATT COL Richard H Outzen OPDAT Jon Smibert TREAS Dan Rountree POL/ECON John Cockrell AMB Michael P. McKinley POL/MIL Stephen Lynagh CG Ian Hillman POSHO Paul Bottse DCM David E. Lindwall SDO/DATT Ralph Shield PAO Hilary Olsin-Windecker AMB Donald Lu GSO Andrew McClearn CON Christopher Beard RSO Tom Barnard DCM Henry Jardine AID William Hammink PAO Valerie O'Brien CLO Cheri Vaughan GSO Chad Pittman DEA Craig M. Wiles RSO Jorge Conrado ECON Amy Holman AID Marcus Johnson FAA Mel Cintron CLO A/Clo Tracy Voight-Athearn FMO James Paravonian ECON Don Brown IMO Wade Martin EEO Shane Child IPO Scott Ternus FMO Craig Kennedy ISO Lysa Giuliano IMO Shane Child ISSO Sekou Dembele ISSO Andu Debebe LEGATT Charles F. -

Marek Kvetan (SK)

MAREK KVETAN born: 14.4.1976 Bratislava lives and works: in Bratislava e-mail: [email protected] www.kvetan.net EDUCATION: 1999 – 2001 - Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Bratislava, Slovakia Department of Painting, Prof. D. Fischer 1999 - Technical University Brno - Faculty of Fine Arts, Czech Republic Department of Multimedia-Performance-Video, Prof. Keiko Sei 1995 - 1999 - Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Bratislava, Slovakia Department of Sculpture, Intermedia Studio of Free Creativity, Prof. J. Bartusz 1990 - 1994 - Secondary School of Applied Arts, Kremnica, Slovakia GRANTS: 2005 - Foundation - Center for Contemporary Arts, Bratislava, Slovakia 2004 - Foundation - Center for Contemporary Arts, Bratislava, Slovakia - MKSR, Bratislava, Slovakia 2002 - Foundation - Center for Contemporary Arts, Bratislava, Slovakia 2001 - Jana & Milan Jelinek - stiftung, Baar, Switzerland - FVU – graduate scholarship, Bratislava, Slovakia 2000 - Soros Center for Contemporary Arts, Bratislava, Slovakia 1998 - Jana & Milan Jelinek - stiftung, Baar, Switzerland - Soros Center for Contemporary Arts - Slovakia, Bratislava, Slovakia 1997 - Soros Center for Contemporary Arts - Slovakia, Bratislava, Slovakia AWARDS: 2007 - finalist - Prize NG 333, National Gallery Prague, Czech Republic 2003 - Grand prix - Contemporary Slovak Graphic Triennial, State Gallery in Banská Bystrica, Slovakia 2000 - finalist - TONAL - Slovak Visual Arts Prize, Bratislava, Slovakia 1998 - finalist - Slovak Young Visual Art Prize, Bratislava, Slovakia ART RESIDENCE: 2007 - FUTURA, Karlin Studios, Prague, Czech Republik 2000 - The Headlends Center for the Arts in Sausalito, California, USA REPRESENTED IN THE COLLECTIONS: - Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Bratislava, Slovakia - National Gallery Prague, Czech Republic - State Gallery, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia - Siemens, Wien, Austria - CBK, Dordrecht, Netherlands - GMB City Gallery Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovakia SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2007 - Marek Kvetan & Marko Blazo, Siemnes ArtLAB, Wien, Austria 2005 - Monosti automatickch opráv (eng. -

Newly Established Breeding Sites of the Barnacle Goose Branta Leucopsis in North-Western Europe – an Overview of Breeding Habitats and Colony Development

244 N. FEIGE et al.: New established breeding sites of the Barnacle Goose in North-western Europe Newly established breeding sites of the Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis in North-western Europe – an overview of breeding habitats and colony development Nicole Feige, Henk P. van der Jeugd, Alexandra J. van der Graaf, Kjell Larsson, Aivar Leito & Julia Stahl Feige, N., H. P. van der Jeugd, A. J. van der Graaf, K. Larsson, A. Leito, A. & J. Stahl 2008: Newly established breeding sites of the Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis in North-western Europe – an overview of breeding habitats and colony development. Vogelwelt 129: 244–252. Traditional breeding grounds of the Russian Barnacle Goose population are at the Barents Sea in the Russian Arctic. During the last decades, the population increased and expanded the breeding area by establishing new breeding colonies at lower latitudes. Breeding numbers outside arctic Russia amounted to about 12,000 pairs in 2005. By means of a questionnaire, information about breeding habitat characteristics and colony size, colony growth and goose density were collected from breeding areas outside Russia. This paper gives an overview about the new breeding sites and their development in Finland, Estonia, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands and Belgium. Statistical analyses showed significant differences in habitat characteristics and population parameters between North Sea and Baltic breeding sites. Colonies at the North Sea are growing rapidly, whereas in Sweden the growth has levelled off in recent years.I n Estonia numbers are even decreasing. On the basis of their breeding site choice, the flyway population of BarnacleG eese traditionally breeding in the Russian Arctic can be divided into three sub-populations: the Barents Sea population, the Baltic population and the North Sea population. -

Tartu Kuvand Reisisihtkohana Kohalike Ja Välismaiste Turismiekspertide Seas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library Tartu Ülikool Sotsiaalteaduskond Ajakirjanduse ja kommunikatsiooni instituut Tartu kuvand reisisihtkohana kohalike ja välismaiste turismiekspertide seas Bakalaureusetöö (4 AP) Autor: Maarja Ojamaa Juhendaja: Margit Keller, PhD Tartu 2009 Sisukord Sissejuhatus ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Töö teoreetilised ja empiirilised lähtekohad ............................................................................ 7 1.1. Turism .................................................................................................................................. 7 1.2. Reisisihtkoha maine ja selle tekkimine ............................................................................ 9 1.2.1. Võimalikud takistused positiivse maine kujunemisel ............................................. 11 1.3. Sihtkoha bränd ja brändimine ........................................................................................ 12 1.4. Teised uuringud sarnastel teemadel ............................................................................... 15 1.5. Uuringu objekt: Tartu reisisihtkohana ............................................................................ 16 1.5.1. Turismistatistika Eestis ja Tartus ............................................................................ 17 2. Uurimisküsimused ................................................................................................................ -

Preuzmi PDF 966.8 KB

Razvoj automobilske industrije u Istočnoj Europi Fuštin, Ivan Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:217:444560 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of Faculty of Science - University of Zagreb Sveučilište u Zagrebu Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Geografski odsjek Ivan Fuštin Razvoj automobilske industrije u Istočnoj Europi Prvostupnički rad Mentor: prof. dr. sc. Zoran Stiperski Ocjena: _______________________ Potpis: _______________________ Zagreb, 2020. godina. TEMELJNA DOKUMENTACIJSKA KARTICA Sveučilište u Zagrebu Prvostupnički rad Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Geografski odsjek Razvoj automobilske industrije u Istočnoj Europi Ivan Fuštin Izvadak: U ovom radu cilj je analizirati razvoj i propast automobilske industrije te njezinu revitalizaciju. Utvrditi uzroke propasti automobilskih kompanija u promatranom prostoru te navesti faktore relokacije iste. Također, usporediti čimbenike jače zastupljenosti automobilske industrije u državama u promatranom prostoru. 22 stranica, 1 grafičkih priloga, 1 tablica, 3 bibliografskih referenci; izvornik na hrvatskom jeziku Ključne riječi: automobilska industrija, socijalizam, propast, revitalizacija Voditelj: prof. dr. sc. Zoran Stiperski Tema prihvaćena: 13. 2. 2020. Datum obrane: -

ON the PATH of RECOVERY TOP 100 COMPANIES > PAGE 6

CROATIA, KOSOVO, MACEDONIA, MOLDOVA, MOLDOVA, MACEDONIA, KOSOVO, CROATIA, MONTENEGRO, ROMANIA, SERBIA, SLOVENIA ALBANIA, BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, BULGARIA, BULGARIA, ALBANIA, BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, ON THE PATH ROMANIA’S BCR SHINES NO QUICK RECOVERY FOR OF RECOVERY AGAIN IN TOP 100 BANKS SEE INSURERS IN 2011 RANKING TOP 100 COMPANIES TOP 100 BANKS TOP 100 INSURERS > PAGE 6 > PAGE 22 > PAGE 30 interviews, analyses, features and expert commentsperspective for to anthe additional SEE market real-time coverage of business and financial news from SEE investment intelligence in key industries Real-time solutions for your business in Southeastast Europe The business news and analyses of SeeNews are also available on your Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters terminals. wire.seenews.com editorial This fi fth annual edition of SeeNews TOP 100 SEE has tried to build on the previous issues by off ering even richer content, more features, analyses and a variety of views on the economy of Southeast Europe (SEE) and the region’s major companies. We have prepared an entirely new ranking called TOP 100 listed companies, part of the TOP listed companies section, giving its rationale along with a feature story on the stock exchanges in the region. For the fi rst time we have included research on Turkey and Greece, setting the scene for companies from the two countries to enter the TOP 100 rankings in the future. The scope has been broadened with a chapter dedicated to culture and the leisure industry, called SEE colours, which brings the region into the wider context of united Europe. One of the highlights of the 2012 edition is a feature writ- ten by the President of the European Bank for Reconstruc- tion and Development, Sir Suma Chakrabarti. -

Mga. Lucia Nimcová, Laborecká 7, 066 01 Humenné, Slovakia

mga. lucia nimcová, laborecká 7, 066 01 humenné, slovakia [email protected] www.luco.sk tel: ++ 421 905 899 186 born: 11/11/1977, humenné grants & awards: 2004 mio photo awards - kasahara michiko prize, osaka, japan joop swart masterclass / world press photo, amsterdam, netherlands künstlerhaus schloss wiepersdorf, germany – residency winner, fujifilm euro press photo awards, national round, bratislava, slovakia 2003 institute for public affairs, bratislava, slovakia - photo survey on state of the slovak society kulturkontakt, wien, austria - artist in residence 2002 winner, who is who, lidové noviny & who is who agency, prague, czech republic education: 1996 - 2003 institute of creative photography, silesian university, opava, czech republic 1992 - 1996 secondary school for applied arts, košice, slovakia 1984 - 1992 primary school with enhanced ukrainian language classes, humenné, slovakia books 2003 slovensko 003 / slovakia 003, fotofo / ivo, bratislava, isbn: 80 85739-36-4 catalogues: 2004 instant europe, villa manin - centro d'arte contemporanea, codroipo 2004 pride, joop swart masterclass, stichting world press photo, amsterdam, issn: 1568-6809 2004 young photographers 2004, foundation of visual education, łodz 2004 mio photo award 2004, osaka 2003 private women, fotofo, bratislava 2002 czech and slovak photography of the 1980s and 1990s, muzeum umění, olomouc, isbn: 80-85227-50-9 solo exhibitions: 2004 "slovakia 003", slovak institute, prague, czech republic "slovakia 003", gallery fiducia, ostrava, czech republic 2003 "slovakia 003", -

Eestimaa Looduse Fond Vilsandi Rahvuspargi Kaitsekorralduskava

ELF-i poolt Keskkonnaametile üle antud kinnitamata versioon Eestimaa Looduse Fond Vilsandi rahvuspargi kaitsekorralduskava aastateks 2011-2020 Liis Kuresoo ja Kaupo Kohv Tartu-Vilsandi 2010 ELF-i poolt Keskkonnaametile üle antud kinnitamata versioon SISUKORD Sissejuhatus ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Vilsandi rahvuspargi iseloomustus ......................................................................................... 8 1.1 Vilsandi rahvuspargi asend .......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Vilsandi rahvuspargi geomorfoloogiline ja bioloogiline iseloomustus ....................... 8 1.3 Vilsandi rahvuspargi kaitse-eesmärk, kaitsekord ja rahvusvaheline staatus................ 8 1.4 Maakasutus ja maaomand ............................................................................................ 9 1.5 Huvigrupid ................................................................................................................. 13 1.6 Vilsandi rahvuspargi visioon ..................................................................................... 16 2 Väärtused ja kaitse-eesmärgid .............................................................................................. 17 Elustik ........................................................................................................................................... 17 2.1 Linnustik ...................................................................................................................