Die Welt Der Slaven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural and Scientific Collaboration Between Czechoslovakia and Cuba in the 1960S, 70S and 80Se Words and Silences, Vol 6, No 2 December 2012 Pp

Hana Bortlova “It Was a Call from the Revolution” – Cultural and Scientific Collaboration between Czechoslovakia and Cuba in the 1960s, 70s and 80se Words and Silences, Vol 6, No 2 December 2012 Pp. 12-17 cc International Oral History Association Words and Silences is the official on-line journal of the International Oral History Association. It is an internationally peer reviewed, high quality forum for oral historians from a wide range of disciplines and a means for the professional community to share projects and current trends of oral history from around the world. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. wordsandsilences.org ISSN 1405-6410 Online ISSN 2222-4181 “IT WAS A CALL FROM THE REVOLUTION” – CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC COLLABORATION BETWEEN CZECHOSLOVAKIA AND CUBA IN THE 1960S, 70S AND 80S Hana Bortlova Oral History Center Institute for Contemporary History Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic [email protected] Although traditional relationships between Cuba Culture was established in Prague. In the scientific field, the Czechoslovak Academy of and Czechoslovakia, economic above all, go back Sciences contributed significantly to the creation further than the second half of the twentieth of the Academy of Sciences of Cuba; starting in century, the political and social changes in Cuba at 1963 there was an agreement to directly the end of the fifties and the beginning of the collaborate between the two organizations. The sixties and the rise of Fidel Castro to power and his institutes intensely collaborated above all on inclination to Marxism-Leninism were what biological science, but there was also important marked the start of the close contact between the collaboration in the fields of geography, geology, two countries that would last three decades. -

25 Years Freedom in Bulgaria

25 YEARS FREEDOM IN BULGARIA CIVIC EDUCATION | TRANSITION | BERLIN WALL | PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA | FREEDOM | 1989 | INTERPRETATIONS | OPEN LESSONS | MYTHS | LEGENDS | TOTALITARIAN PAST | DESTALINIZATION | BELENE CAMPS | GEORGI MARKOV | FUTURE | CITIZENS | EAST | WEST | SECURITY SERVICE | ECOGLASNOST | CIVIL DUTY AWARD | ANNIVERSARY | COMMUNISM | CAPITALISM | ARCHIVES | REMEMBRANCE| DISSIDENTS | ZHELYO ZHELEV | RADIO FREE EUROPE | VISEGRAD FOUR | HISTORY| POLITICAL STANDARTS | RULE OF LAW | FREE MEDIA | NOSTALGIA | REGIME| MEMORIES | RATIONALIZATION | HUMAN RIGHTS | HOPE | NOW AND THEN | DISCUSSING | VISUAL EVIDENCES | REPRESSIONS | HERITAGE | INTELLECTUAL ELITE | IRON CURTAIN | CENCORSHIP | GENERATIONS | LESSONS | TRANSFORMATION | TODOR ZHIVKOV | COLD WAR | INSTITUTIONS | BEGINNING | INFORMATION | RECONCILIATION | FACTS | EXPERIENCES | CONSENSUS | DISTORTIONS | MARKET ECONOMY | REFORM | UNEMPLOYMENT | THE BIG EXCURSION | IDEOLOGY | PUBLIC OPINION | NATIONAL INITIATIVE | TRUTH | ELECTIONS years ee B 25 years free Bulgaria is a civic initiative under the auspices of the President of Bulgaria, organized by Sofia Platform Fr ulgaria years CONTENT ee B Fr ulgaria CIVIC EDUCATION | TRANSITION | BERLIN WALL | PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA | FREEDOM | 1989 | INTERPRETATIONS | OPEN LESSONS | MYTHS | LEGENDS | TOTALITARIAN PAST | 1. 25 Years Freedom in Bulgaria 02 DESTALINIZATION | BELENE CAMPS | GEORGI MARKOV | FUTURE | CITIZENS | EAST | WEST | SECURITY 2. Remembrance and Culture 04 SERVICE | ECOGLASNOST | CIVIL DUTY AWARD -

Exporting Holidays: Bulgarian Tourism in the Scandinavian Market in the 1960S and 1970S Elitza Stanoeva

Exporting holidays: Bulgarian tourism in the Scandinavian market in the 1960s and 1970s Elitza Stanoeva In the second half of the 1950s, socialist Bulgaria sought to join the new global business of mass tourism. Although lacking a comprehensive strategy, a long-term plan, or even a coherent concept of tourism, the ambition to develop a tourist hub with international outreach and large hard-currency profits was there from the start. In pursuit of this ambition, both tourism’s infrastructure and institutional network mushroomed, and by the mid-1960s the contribution of international tourism to the Bulgarian economy was acknowledged to be indispensable. Hosting capitalist tourists who paid with hard cash was the only way to compensate, at least in part, for the trade deficits Bulgaria incurred vis-à-vis their home countries. Investment in recreational facilities first appeared on the agenda of the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) in the mid-1950s, under two different motivations. Providing holiday leisure for the masses was integral to the social reforms in the aftermath of de-Stalinization, under the new ideological slogan of “satisfying the growing material needs” of Bulgarian workers.1 Yet, the subsequent boom in resort construction was also prompted by economic pragmatism, and was geared towards meeting the demands of a foreign clientele. Reflecting these heterogeneous incentives, government strategy from the onset differentiated “economic tourism” from “social tourism.”2 While the latter was a socialist welfare service for the domestic public, economic tourism predominantly targeted foreign visitors from the socialist bloc and beyond.3 Shaped by divergent operational logics and administered by separate agencies, facilities for the two categories of holidaymakers—high-paying foreigners and state-subsidized locals— developed side by side, yet apart from one another. -

Economic and Social Differences Across the Polish-East German Open Border, 1972-1980

UNEQUAL FRIENDSHIP: ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DIFFERENCES ACROSS THE POLISH-EAST GERMAN OPEN BORDER, 1972-1980. Michael A. Skalski A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Konrad H. Jarausch Karen Auerbach Chad Bryant © 2015 Michael A. Skalski ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MICHAEL A. SKALSKI: Unequal Friendship: Economic and Social Differences across the Polish-East German Open Border, 1972-1980 (Under the direction of Konrad H. Jarausch) In 1972, Poland and the German Democratic Republic opened their mutual border to free travel. Although this arrangement worked for some time, tensions arose quickly contributing to the closing of the border in 1980. This thesis explores the economic, political, and social reasons for the malfunctioning of the open border in order to shed light on the relationship between Poland and East Germany in particular, and between society and dictatorship in general. It reveals that differences in economic conditions and ideological engagement in both countries resulted in mass buy-outs of East German goods and transnational contacts of dissidents, which alienated segments of the population and threatened the stability of the system. Seeing open borders as an important element of the “welfare dictatorship,” this study concludes that the GDR was reluctant to close the border again. Only fear of opposition developing in Poland forced the SED to rescind the free-travel agreement. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been possible without the assistance of many people. -

European Socialist Regimes' Fateful Engagement with the West

7 Balancing Between Socialist Internationalism and Economic Internationalisation Bulgaria’s economic contacts with the EEC Elitza Stanoeva During his first visit to Bonn in 1975, Todor Zhivkov, Bulgaria’s party leader and head of state for nearly two decades, met an assembly of West German entre- preneurs, and not just any, but the top management of powerful concerns such as Krupp and Daimler-Benz – ‘the monopolies and firms which control 50% of the economic potential of the country’, as argued in the lauding report on the visit afterwards submitted to the politburo of the Bulgarian Communist Party (Balgarska komunisticheska partiya [BKP]).1 Five pages later, the same report highlighted Zhivkov’s witty retort to an SPD politician: ‘Regardless of whether the elections are won by the social democrats or the Christian democrats, Beitz, the boss of Krupp, who represents capitalism in Germany, will remain in place’.2 The irony of criticising West German politicians for being in cahoots with the corporate world while trying to strike a deal with the very same corporations passed unnoticed. After all, Zhivkov went to Bonn to do business, namely to give a boost to the strained Bulgarian economy by securing a long-term loan from the West German government. In this mission, which ultimately failed, he did not shy away from reaching out to the corporate milieu with promises of high profits in the Bulgarian market. Neither did he shy away from depicting his native socialist economy as one overpowered by ‘trade unions, party organisations and the like whom even we cannot cope with’ – in order to divert West German requests for direct investment options.3 Rather than being an anecdote on political duplicity, Zhivkov’s conflicting statements, admittedly aimed at different audiences, illustrate the duality in Bul- garia’s policy of doing business with the West as a balancing act between socialist internationalism and economic internationalisation. -

The Political Logic of State-Socialist Material Culture

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2009;51(2):426–459. 0010-4175/09 $15.00 #2009 Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417509000188 Goods and States: The Political Logic of State-Socialist Material Culture KRISZTINA FEHE´ RVA´ RY University of Michigan In the two decades since the fall of state socialism, the widespread phenomenon of nostalgie in the former Soviet satellites has made clear that the everyday life of state socialism, contrary to stereotype, was experienced and is remembered in color.1 Nonetheless, popular accounts continue to depict the Soviet bloc as gray and colorless. As Paul Manning (2007) has argued, color becomes a powerful tool for legitimating not only capitalism, but democratic governance as well. An American journalist, for example, recently reflected on her own experience in the region over a number of decades: It’s hard to communicate how colorless and shockingly gray it was behind the Iron Curtain ... the only color was the red of Communist banners. Stores had nothing to sell. There wasn’t enough food.... Lines formed whenever something, anything, was for sale. The fatigue of daily life was all over their faces. Now...fur-clad women con- fidently stride across the winter ice in stiletto heels. Stores have sales... upscale cafe´s cater to cosmopolitan clients, and magazine stands, once so strictly controlled, rival Acknowledgments: This paper has been in gestation for a long time, and I am indebted to a number of people for their comments on various drafts, including Leora Auslander, John Comaroff, Nancy Munn, Paul Johnson, Webb Keane, Katherine Verdery, and Genevie`ve Zubrzycki. -

Povl Tiedemann's Meritter Og Historik

Povl Tiedemann’s meritter og historik 1 Til Anne fra Far På opfordring af Mor 2 Dahls Foto, Holstebro, 1955 3 Indholdsoversigt Side 1948 – 1955 Stenhøj 6 1955 – 1962 Grundskole 7 1962 – 1965 Realskole 9 1965 – 1968 Shippingelev 11 1968 – 1968 Shipping Volontør 16 1968 – 1970 Handelsgymnasium 21 1970 – 1975 Handelshøjskole 25 1976 – 1976 Erhv. Eksportfremme Sekr. 33 1976 – 1977 MÆRSK 34 1977 – 1981 Handelskammeret 40 1981 – 1987 LEGO 53 -Power-Play i Østeuropa -Statshandel -Modkøb og valutaforhold -Modkøbsvarer og distribution -Interessante eksempler -Østeuropæiske kontakter -Anvendelse af LEGO vareprøver -Rejse- og repræsentationsforhold -Leipzig Messen – business basis -Poznan Messen 1981 – optakt til slutspil -Nye muligheder i USSR -USSR stop og genstart i Moskva -Åbning til Kina -Diverse omkring Kina -Modkøb intensiveres og problematiseres -Finale LEGO -Et par centrale navne -Hændelser og iagttagelser under vejs 106 -Nationale forskelligheder -Kontakt / forhandling / samarbejde -Overvågning -Produktudvikling / innovation / kreativitet -Overordnede betragtninger -Efterskrift - ”Fugl Føniks” 134 1987 – 1991 Handelskammeret 136 4 -Sidste tur gennem ingenmandsland 1992 – 1996 Div. + underv. + censorakt. 143 1996 – 2009 Civiløkonomerne 147 -Hændelser under vejs 2009 – 2013 Censorsekretariaterne / censorerne.dk 170 -Diverse ”Red Tape” -Hændelser under vejs 2013 – 2018 Censor IT / 178 Censorformandskaberne -Sporskifte til formandskaberne 2014 – XXXX Ældrerådet i Vejle Kommune 182 Lidt om min Eva 183 SummaSummarum – Eftertænksomheder 185 Lidt fra ”tidsmaskinen” 191 Personal Card – CV i TACIS opstilling 195 Hovedaktiviteter for Civiløkonomerne 205 Billeder og -forklaringer 209 Kalligrafi og protokol 241 ”Kineserier” fra LEGO-personalebladet Klodshans 245 Bibliografi 256 Links 259 5 1948 – 1955: Stenhøj Opvokset som den yngste – årgang 1948 – blandt 3 søskende, på en landejendom på ”Stenhøj”, Foldingbrovej 15, Rødekro, 13 km. -

Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin

Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin Boston University During the 1970s, a joke circulated in the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, that deftly paraphrases the peculiar problem of money in Soviet-style regimes. Two men, eager to enrich themselves by producing counterfeit bank notes, mistakenly print 70-mark bills. To improve their chances of unloading the fake notes without getting caught, they decide to travel to the provinces. Sure enough, they find a sleepy state-run retail outlet in a remote East German village. The first forger turns to his colleague and says, “Maybe you should try to buy a pack of cigarettes with the 70-mark bill first.” The second counterfeiter agrees, and disappears into the store. When he returns a few minutes later, the first man asks him how it went. “Great,” says the second man, “they didn’t notice anything at all. Here are the cigarettes, and here’s our change: two 30-mark bills and two 4-mark bills.”1 Like much of the black humor inspired by authoritarian rule, the joke makes use of irony to render unlike things commensurate. This particular joke acquires a subversive edge from its equation of communism with forgery. The two men successfully dupe the state-run store into accepting their phony bills, but the socialist state replies in kind by passing on equally fake money. The joke does not exhaust itself, however, in an attack on the moral integrity of communism, which responds to one crime with another, or even with the powerful suggestion that any regime that counterfeits its own currency must be a sham. -

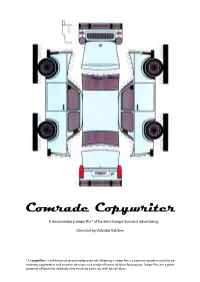

Comrade Copywriter

Comrade Copywriter A documentary swipe file* of Eastern Europe Socialist advertising. Directed by Valentin Valchev. *A swipe file is a collection of tested and proven ads. Keeping a swipe file is a common practice used by ad- vertising copywriters and creative directors as a ready reference of ideas for projects. Swipe files are a great jumping-off point for anybody who needs to come up with lots of ideas. 1 Synopsis “What is the difference between Capitalism and Socialism? Capitalism is the exploitation of humans by humans. Socialism is the opposite.” an East German joke from the times of the DDR For more than half a century a vast part of the world inhabited by millions of people lived isolated behind an ideological wall, forcedly kept within the Utopia of a social experiment. The ‘brave new world’ of state controlled bureaucratic planned economy was based on state property instead of private and restric- tions instead of initiative. Advertising, as well as Competition and Consumerism, were all derogatory words stigmatizing the world outside the Wall – the world of Capitalism, Imperialism and Coca Cola. On the borderline where the two antagonistic worlds met, a weird phenomenon occurred – the Com Ads. This was comrade copywriter’s attempt to peep from behind the wall and present the socialist utopia as a normal part of the world. Welcome to comrade copywriter’s brave new world! Marketing - in a strictly controlled and anti-market oriented society. Branding - of deficient or even non-existant products, in the situation of stagna- tion and crisis; you could watch a Trabi TV ad every day and still wait for 15 years to bye one. -

Securitas Im Perii

Ulrich Ferdinand Kinsky: A Nobleman, Aviator, Racing Driver and Sportsman in the 20th Century Michal Plavec Ulrich Ferdinand Kinsky (15 August 1893 – 19 December 1938) came from a noble Czech family but, unlike many of his relatives, sided with the Nazis and played a key role during Lord Runciman’s mission to Czechoslovakia in 1938. He embraced the Munich Agreement and was happy to see his farm near Česká Kamenice becoming part of Nazi Germany. He died in Vienna before World War II started. It is a lesser known fact that he served in the Austro‑Hungarian Air Force during the Great War, first as an observer and later as a pilot. Flying was his great passion; he owned three airplanes and often flew them all over Europe between the two wars. He had private airports built near the manors on his property – in Klešice near Heřmanův Městec and in Dolní Kamenice near Česká Kamenice. He also served as the President of Aus‑ tria Aero Club. He was even a successful race car driver in the 1920s and remained a passionate polo player until death. Although he was the progeny of the youngest son of the 7th Prince Kinsky, he became the 10th Prince Kinsky after the death of his two uncles and father. In addition to a palace in Vienna and the two aforementioned farming estates, he also owned large farms in Choceň, Rosice and Zlonice. Kinsky divorced his first wife Katalina née Szechényi likely because he believed she was guilty of the premature death of their son Ulrich at age eleven. -

Arab Students Inside the Soviet Bloc : a Case Study on Czechoslovakia During the 1950S and 60S

European Scientific Journal June 2014 /SPECIAL/ edition vol.2 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 ARAB STUDENTS INSIDE THE SOVIET BLOC : A CASE STUDY ON CZECHOSLOVAKIA DURING THE 1950S AND 60S Daniela Hannova, MA Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts, Department of World History Abstract The paper focuses on the phenomenon of students from the so-called less developed countries in communist Czechoslovakia, specifically Arab students in the 50s and 60s of the twentieth century. The first part of the paper focuses on a broader political and social context. Because it was the first wave of Arab scholarship holders supported by the Czechoslovak government to arrive at the end of the 50s, it is crucial to describe the shape of negotiations between the Czechoslovak and Arab sides. The second part of the paper emphasizes cultural agreements and types of studying in Czechoslovakia. Arriving abroad, preparatory language courses, everyday life of Arab students in Czechoslovakia and the conflicts they had faced are analyzed in the following subchapters. The problem of Arab student adaptation to the new environment and troubles caused by cultural differences are illuminated in the framework of these thematic sections. The final part of the paper outlines the Arab absolvents’ fates and their contacts with Czechoslovakia after ending their university studies and returning to their homeland. Keywords: Students, universities, Czechoslovakia after 1948, Communism, everyday life, cultural history Introduction The phenomenon of students from the so-called less developed countries in the Soviet Bloc is a part of history, where a lot of topics and possible methodological approaches meet. -

Marcheva, Il. the Policy of Economic Modernisation in Bulgaria During the Cold War

е-списание в областта на хуманитаристиката Х-ХХI в. год. IV, 2016, брой 8; ISSN 1314-9067 http://www.abcdar.com Marcheva, Il. The Policy of Economic Modernisation in Bulgaria during the Cold War. 2016, 640 p. ABSTRACT The study of the policy of economic modernisation in Bulgaria during the Cold War shows that it was a relatively successful process. During that period, Bulgaria became industrial and urbanised country with modern agriculture and a vast army of engineers and technicians. These processes were explored through historical approaches on the basis of primary sources and secondary literature. They were placed in the context of the Cold War period, from 1946 until 1989. The author shows that at a time when the world was divided into two warring camps, two simultaneous factors were at work – the internal political factor – the Bulgarian Communist Party, and its foreign policy mentor – the USSR. The resulting symbiosis between the party and the state furthered the implementation of Soviet-modelled industrialisation and modernisation imposed for economic and political reasons. After the end of the Cold War the favourable foreign political and economic conditions for economic modernisation disappeared. Under the new circumstances the country had to adjust to a new paradigm – that of the information еra, not of the industrial era, in the conditions of the victory of neoliberalism. Илияна Марчева. Политиката за стопанска модернизация в България по време на Студената война, изд. Летера, 2016, 640 с. РЕЗЮМЕ В монографията за пръв път е представена цялостно политиката за превръщане на България от аграрна в индустриална и урбанизирана страна с всички произтичащи от е-списание в областта на хуманитаристиката Х-ХХI в.