The Political Logic of State-Socialist Material Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Welt Der Slaven

D I E W E L T D E R S L AV E N S A M M E L B Ä N D E · С Б О Р Н И К И Herausgegeben von Peter Rehder (München) und Igor Smirnov (Konstanz) Band 54 2014 Verlag Otto Sagner München – Berlin – Washington/D.C. Sammelband_Slawistik.indd 2 07.11.14 13:29 Fashion, Consumption and Everyday Culture in the Soviet Union between 1945 and 1985 Edited by Eva Hausbacher Elena Huber Julia Hargaßner 2014 Verlag Otto Sagner München – Berlin – Washington/D.C. Sammelband_Slawistik.indd 3 07.11.14 13:29 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Vorwort ............................................................................................................................... 7 Sozialistische Mode Djurdja Bartlett ................................................................................................................ 9 Myth and Reality: Five-Year Plans and Socialist Fashion Ulrike Goldschweer ......................................................................................................... 31 Consumption / Culture / Communism: The Significance of Terminology or Some Realities and Myths of Socialist Consumption Катарина Клингсайс .................................................................................................... 49 Этот многоликий мир моды. Образец позднесоветского дискурса моды Mode und Gesellschaft Анна Иванова ................................................................................................................. 73 «Самопал по фирму»: Подпольное производство одежды в СССР в 1960–1980-е годы Irina Mukhina ................................................................................................................ -

Economic and Social Differences Across the Polish-East German Open Border, 1972-1980

UNEQUAL FRIENDSHIP: ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DIFFERENCES ACROSS THE POLISH-EAST GERMAN OPEN BORDER, 1972-1980. Michael A. Skalski A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Konrad H. Jarausch Karen Auerbach Chad Bryant © 2015 Michael A. Skalski ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MICHAEL A. SKALSKI: Unequal Friendship: Economic and Social Differences across the Polish-East German Open Border, 1972-1980 (Under the direction of Konrad H. Jarausch) In 1972, Poland and the German Democratic Republic opened their mutual border to free travel. Although this arrangement worked for some time, tensions arose quickly contributing to the closing of the border in 1980. This thesis explores the economic, political, and social reasons for the malfunctioning of the open border in order to shed light on the relationship between Poland and East Germany in particular, and between society and dictatorship in general. It reveals that differences in economic conditions and ideological engagement in both countries resulted in mass buy-outs of East German goods and transnational contacts of dissidents, which alienated segments of the population and threatened the stability of the system. Seeing open borders as an important element of the “welfare dictatorship,” this study concludes that the GDR was reluctant to close the border again. Only fear of opposition developing in Poland forced the SED to rescind the free-travel agreement. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been possible without the assistance of many people. -

Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin

Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin Boston University During the 1970s, a joke circulated in the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, that deftly paraphrases the peculiar problem of money in Soviet-style regimes. Two men, eager to enrich themselves by producing counterfeit bank notes, mistakenly print 70-mark bills. To improve their chances of unloading the fake notes without getting caught, they decide to travel to the provinces. Sure enough, they find a sleepy state-run retail outlet in a remote East German village. The first forger turns to his colleague and says, “Maybe you should try to buy a pack of cigarettes with the 70-mark bill first.” The second counterfeiter agrees, and disappears into the store. When he returns a few minutes later, the first man asks him how it went. “Great,” says the second man, “they didn’t notice anything at all. Here are the cigarettes, and here’s our change: two 30-mark bills and two 4-mark bills.”1 Like much of the black humor inspired by authoritarian rule, the joke makes use of irony to render unlike things commensurate. This particular joke acquires a subversive edge from its equation of communism with forgery. The two men successfully dupe the state-run store into accepting their phony bills, but the socialist state replies in kind by passing on equally fake money. The joke does not exhaust itself, however, in an attack on the moral integrity of communism, which responds to one crime with another, or even with the powerful suggestion that any regime that counterfeits its own currency must be a sham. -

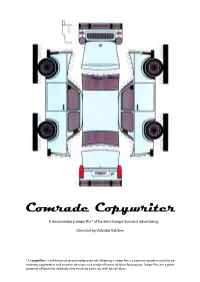

Comrade Copywriter

Comrade Copywriter A documentary swipe file* of Eastern Europe Socialist advertising. Directed by Valentin Valchev. *A swipe file is a collection of tested and proven ads. Keeping a swipe file is a common practice used by ad- vertising copywriters and creative directors as a ready reference of ideas for projects. Swipe files are a great jumping-off point for anybody who needs to come up with lots of ideas. 1 Synopsis “What is the difference between Capitalism and Socialism? Capitalism is the exploitation of humans by humans. Socialism is the opposite.” an East German joke from the times of the DDR For more than half a century a vast part of the world inhabited by millions of people lived isolated behind an ideological wall, forcedly kept within the Utopia of a social experiment. The ‘brave new world’ of state controlled bureaucratic planned economy was based on state property instead of private and restric- tions instead of initiative. Advertising, as well as Competition and Consumerism, were all derogatory words stigmatizing the world outside the Wall – the world of Capitalism, Imperialism and Coca Cola. On the borderline where the two antagonistic worlds met, a weird phenomenon occurred – the Com Ads. This was comrade copywriter’s attempt to peep from behind the wall and present the socialist utopia as a normal part of the world. Welcome to comrade copywriter’s brave new world! Marketing - in a strictly controlled and anti-market oriented society. Branding - of deficient or even non-existant products, in the situation of stagna- tion and crisis; you could watch a Trabi TV ad every day and still wait for 15 years to bye one. -

44H5r8sz.Pdf

UC Berkeley Other Recent Work Title Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/44h5r8sz Author Zatlin, Jonathan R Publication Date 2007-04-28 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin Boston University During the 1970s, a joke circulated in the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, that deftly paraphrases the peculiar problem of money in Soviet-style regimes. Two men, eager to enrich themselves by producing counterfeit bank notes, mistakenly print 70-mark bills. To improve their chances of unloading the fake notes without getting caught, they decide to travel to the provinces. Sure enough, they find a sleepy state-run retail outlet in a remote East German village. The first forger turns to his colleague and says, “Maybe you should try to buy a pack of cigarettes with the 70-mark bill first.” The second counterfeiter agrees, and disappears into the store. When he returns a few minutes later, the first man asks him how it went. “Great,” says the second man, “they didn’t notice anything at all. Here are the cigarettes, and here’s our change: two 30-mark bills and two 4-mark bills.”1 Like much of the black humor inspired by authoritarian rule, the joke makes use of irony to render unlike things commensurate. This particular joke acquires a subversive edge from its equation of communism with forgery. The two men successfully dupe the state-run store into accepting their phony bills, but the socialist state replies in kind by passing on equally fake money. -

Return of the Hanseatic League Or How the Baltic Sea Trade Washed Away the Iron Curtain, 1945-1991

Return of the Hanseatic League or How the Baltic Sea Trade Washed Away the Iron Curtain, 1945-1991 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Blusiewicz, Tomasz. 2017. Return of the Hanseatic League or How the Baltic Sea Trade Washed Away the Iron Curtain, 1945-1991. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41141532 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Return of the Hanseatic League or how the Baltic Sea Trade Washed Away the Iron Curtain, 1945-1991 A dissertation presented by Tomasz Blusiewicz to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2017 © 2017 Tomasz Blusiewicz All rights reserved. Professor Alison Frank Johnson Tomasz Blusiewicz Return of the Hanseatic League or how the Baltic Sea Trade Washed Away the Iron Curtain, 1945-1991 Abstract This dissertation develops a comparative perspective on the Baltic region, from Hamburg in the West to Leningrad in the East. Its transnational approach highlights the role played by medieval Hanseatic port cities such as Rostock (East Germany), Szczecin and Gdańsk (Poland), Kaliningrad, Klaipeda, Riga, and Tallinn (Soviet Union), as ‘windows to the world’ that helped the communist-controlled Europe to remain in touch with the West after 1945. -

Text Práce (3.363Mb)

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Diplomová práce 2014 Bc. & Bc. Julie Tomsová Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Ústav hospodářských a sociálních dějin Diplomová práce Julie Tomsová „Zdomácnění“ vědecko-technické revoluce v Československu: inovace v české kuchyni a výživě 50. a 60. let 20. století „Domesticating“ the Scientific-Technological Revolution in Czechoslovakia: innovation in the Czech Kitchen and Alimentation in the 1950s and 1960s Praha 2014 Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Michal Pullmann, PhD. PODĚKOVÁNÍ V první řadě děkuji vedoucímu své diplomové práce, doc. PhDr. Michalu Pullmannovi, Ph.D., za jeho užitečné rady a trpělivé vedení. Rovněž děkuji zaměstnancům Zemského archivu v Opavě za jejich pomoc při studiu archivního fondu státního podniku Galena. Věnováno in memoriam Sibi. PROHLÁŠENÍ „Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně, že jsem řádně citovala všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu.“ V Praze dne ……………… Podpis……………………............ ANOTACE Cílem předkládané diplomové práce je analýza „zdomácnění“ vědecko-technické revoluce a nejvýznamnější proměny alimentárního, tj. potravinového (respektive majícího vztah k výživě), chování české společnosti v 50. a 60. letech 20. století. Zmíněný proces je v této diplomové práci interpretován v kontextu změn režimu a ideologických vzorců v polovině 50. let, které měly napomoci překonat potíže stalinského utopismu – zvýšený důraz na kvalitu -

Puolalaisten Näkemys Kuluttajuudesta Neuvostoliitossa

Puolalaisten näkemys kuluttajuudesta Neuvostoliitossa M i l a O i v a kuinka nouseva kulutuskulttuuri muovasi kaupan toimintatapoja. Tarkastelemalla Neuvostoliiton kuluttajia juuri puolalaisten ulkomaankaupan toimijoiden kautta on mahdollista kartoittaa kuinka toisen sosialistisen valtion myyjät, jotka eivät olleet vastuussa ideologisten tavoitteiden saavuttamisesta vaan ennen kaikkea myynnistä, näkivät kulutuskulttuuriin kehittymisen Neuvos- toliiton markkinoilla. Tutkin tässä artikkelissa kuluttajien paino- arvon kasvua Neuvostoliitossa puolalaisten Toisin kuin kotimaassa, jossa on myyjän mark- valmisvaateviejien käsitysten kautta 1960-luvun kinat, ulkomaankaupassa joudumme tekemisiin alusta 1970-luvun alkuun. Puolan valtiollista tyypillisten ostajan markkinoiden kanssa. On vaateteollisuutta koordinoineen Vaateteolli- äärimmäisen tärkeää että kiinnitämme huomiota suusyhtymän1 ja ulkomaankauppaministeriön vientituotteiden laatuun pysyäksemme mukana alaisuudessa toimineiden ulkomaankauppa- kilpailussa. yhtiöiden2 sisäinen kirjeenvaihto ja raportit (Lainaus Puolan ulkomaankauppaministeriön kuvasivat neuvostoliittolaisten tukkuostajien ja tavaravaihto-osaston Puolan ja Neuvostoliiton kuluttajien makutottumuksia ja niiden muutok- välistä kauppaa käsitelleestä raportista 1968, osa sia. Näitä alkuperäislähteitä käyttäen selvitän, II, 2.) millaisina puolalaiset valmisvaateviejät näkivät neuvostomarkkinat: kenen mielipide – tukkuos- Puolalaiset valmisvaateviejät markkinoivat ener- tajien, vaateammattilaisten vai kuluttajien – oli gisesti tuotteitaan -

The Borders of Friendship: Transnational Travel and Tourism in the East Bloc, 1972-1989

The Borders of Friendship: Transnational Travel and Tourism in the East Bloc, 1972-1989 by Mark Aaron Keck-Szajbel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor John Connelly, Chair Professor David Frick Professor Yuri Slezkine Professor Jason Wittenberg Fall 2013 The Borders of Friendship: Transnational Travel and Tourism in the East Bloc, 1972-1989 Copyright © 2013 by Mark Aaron Keck-Szajbel Abstract The Borders of Friendship: Transnational Travel and Tourism in the East Bloc, 1972-1989 by Mark Aaron Keck-Szajbel Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor John Connelly, Chair The “borders of friendship” was an open border travel project between Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and Poland starting in 1972. The project allowed ordinary citizens to cross borders with a police-issued personal identification card, and citizens of member countries were initially allowed to exchange unlimited amounts of foreign currency. In this episode of liberalized travel – still largely unknown in the West – the number of border-crossings between member states grew from the tens of thousands to the tens of millions within a very brief period. This dissertation analyses the political, economic, social and cultural effects of this open border policy. It first clarifies what motivated authorities in Poland, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia to promote unorganized foreign tourism in the 1970s and 1980s. Then, it explores how authorities encouraged citizens to become tourists. Governments wanted the “borders of friendship” to be successful, but they were unsure how to define success. -

Institute of European Studies (University of California, Berkeley)

Institute of European Studies (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin Boston University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ies/070428 Copyright c 2007 by the author. Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Abstract This paper locates the collapse of East German communism in Marxist- Leninist monetary theory. By exploring the economic and cultural functions of money in East Germany, it argues that the communist party failed to reconcile its ideological aspirations - a society free of the social alienation represented by money and merchandise - with the practical exigencies of governing an industrial society by force. Using representative examples of market failure in production and consumption, the paper shows how the party’s deep-seated hostility to money led to economic inefficiency and waste. Under Honecker, the party sought to improve living standards by trading political liberalization for West German money. Over time, however, this policy devalued the meaning of socialism by undermining the actual currency, facilitating the communist collapse and overdetermining the pace and mode of German unification. Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin Boston University During the 1970s, a joke circulated in the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, that deftly paraphrases the peculiar problem of money in Soviet-style regimes. Two men, eager to enrich themselves by producing counterfeit bank notes, mistakenly print 70-mark bills. To improve their chances of unloading the fake notes without getting caught, they decide to travel to the provinces. -

The Black Market of Late Socialism in the Czech-G

Od pouliční šmeliny ke „strýčkům ze Západu“ Černý trh pozdního socialismu v česko-německém kontextu Adam Havlík Tento text je pokusem o badatelský průnik do dosud méně probádaných oblastí soudobé české a německé historiografi e.1 Zabývá se černým trhem v sedmdesá- tých a osmdesátých letech dvacátého století v bývalé Československé socialistické republice a Německé demokratické republice v komparativní perspektivě. Studie si neklade za cíl podat všeobjímající výklad toho, s čím vším, v jakém množství a jakými cestami se v těchto dvou zemích před rokem 1989 potají obchodova- lo. To ostatně kvůli samotnému charakteru černého trhu ani není proveditelné. Text tedy nepřináší vyčerpávající výčet hospodářských statistik, přestože se i jim na některých místech věnuje. Spíše se snaží zmapovat, kteří historičtí aktéři tvořili „motor“ černého trhu. Badatelská pozornost je přitom výrazněji zaměřena na dva důležité segmenty tehdejšího černého trhu, a to na podloudné obchodování se zahraničním spotřebním zbožím a na devizovou trestnou činnost. Snaží se také rozkrýt, jaké společné znaky v tomto ohledu obě země vykazovaly a jaká lokální specifi ka určovala jejich odlišnost. 1 V současné německé historiografi i již vznikly studie postihující některé aspekty neformál- ních ekonomických aktivit ve 20. století. Několik autorů se soustavně věnovalo např. černé- mu trhu v období bezprostředně po (a částečně během) druhé světové války (viz zejména ZIERENBERG, Malte: Stadt der Schieber: Der Berliner Schwarzmarkt 1939–1950. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2008; MÖRCHEN, Stefan: Schwarzer Markt: Kriminalität, Ord- nung und Moral in Bremen, 1939–1949. Frankfurt/M. – New York, Campus 2011). Z neně- meckých autorů viz např. STEEGE, Paul: Black Market, Cold War: Everyday life in Berlin, 1946–1949. -

Number 114 Private Foreign Exchange

I f l " l ; !' NUMBER 114 PRIVATE FOREIGN EXCHANGE ~~RKETS IN EASTE~~ EUROPE AND THE USSR Jan Vanous Conference on "THE SECOND ECONOMY OF THE USSR11 Sponsored by Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies, The Wilson Center With National Council on Soviet and East European Research January 24- , 1980 • First draft Conference use only; not to be cited or auoted RESEARCH CONFERENCE ON THE SECOND ECONOMY OF THE USSR Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies Hashington, D.C. Jan~J 24-26, 1980 Conference Paoer Private Foreign Exchanp;e l\1arkets In Eastern Europe and the USSR by Jan Vanous University of British Columbia ....") Private Foreign Exchange Markets in Eastern Europe and the USSR1 1. Introduction Recently it has become increasingly evident that in order to understand the functioning of Soviet-type economies both at the macroeconomic and microeconomic level and to find policies that could be used to improve their performance, one has to understand the role of the "second economy" and black markets that exist in these economies. One of the most important black markets in Soviet-type economies is the black market in hard currencies and in hard-currency coupons which are used in special stores that offer consumer goods of superior quality and typically not avai- lable elsewhere. On the demand side, the black market exchange rate of a u.s. dollar and other hard currencies will reflect, among other factors, the relative availability of particular consumer goods in the regular domestic market and in hard-currency stores, consumers' perception of domestic open and hidden infla- tion relative to the open inflation in the West, the degree of domestic political stability, and changes in regulations with respect to travel of domestic residents to the lvest.