Land-Based Aircraft in Antisubmarine Role WWII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War

Author’s Accepted Manuscript Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War Matthew Bradley, Matthew Nealiegh, John Oh, Philip Rothberg, Eric Elster, Norman Rich www.elsevier.com/locate/cpsurg PII: S0011-3840(16)30157-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.004 Reference: YMSG552 To appear in: Current Problems in Surgery Cite this article as: Matthew Bradley, Matthew Nealiegh, John Oh, Philip Rothberg, Eric Elster and Norman Rich, Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War, Current Problems in Surgery, http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.004 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. COMBAT CASUALTY CARE AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE LAST 100 YEARS OF WAR Matthew Bradley, M.D. 1, 2, Matthew Nealiegh, M.D. 1, John Oh, M.D. 1, Philip Rothberg, M.D. 1, Eric Elster M.D. 1, 2, Norman Rich M.D. 1 1 Department of Surgery, Uniformed Services University -Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Wisconsin Ave., Bethesda, MD 20889 2Naval Medical Research Center, 503 Robert Grant Ave., Silver Spring, MD 20910 Corresponding Author: Matthew J. -

Tsetusuo Wakabayashi, Revealed

Tsetusuo Wakabayashi, Revealed By Dwight R. Rider Edited by Eric DeLaBarre Preface Most great works of art begin with an objective in mind; this is not one of them. What follows in the pages below had its genesis in a research effort to determine what, if anything the Japanese General Staff knew of the Manhattan Project and the threat of atomic weapons, in the years before the detonation of an atomic bomb over Hiroshima in August 1945. That project drew out of an intense research effort into Japan’s weapons of mass destruction programs stretching back more than two decades; a project that remains on-going. Unlike a work of art, this paper is actually the result of an epiphany; a sudden realization that allows a problem, in this case the Japanese atomic energy and weapons program of World War II, to be understood from a different perspective. There is nothing in this paper that is not readily accessible to the general public; no access to secret documents, unreported interviews or hidden diaries only recently discovered. The information used in this paper has been, for the most part, available to researchers for nearly 30 years but only rarely reviewed. The paper that follows is simply a narrative of a realization drawn from intense research into the subject. The discoveries revealed herein are the consequence of a closer reading of that information. Other papers will follow. In October of 1946, a young journalist only recently discharged from the US Army in the drawdown following World War II, wrote an article for the Atlanta Constitution, the premier newspaper of the American south. -

Rioting and Time

Rioting and time Collective violence in Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow, 1800-1939 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Matteo Tiratelli School of Social Sciences 1 Table of contents Abstract 4 Declaration & Copyright 5 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter 1 — Rioting and time 7 Chapter 2 — Don’t call it a riot 24 Chapter 3 — Finding riots and describing them 42 Chapter 4 — Riots in space, time and society 64 Chapter 5 — The changing practice of rioting 102 Chapter 6 — The career of a riot: triggers and causes 132 Chapter 7 — How do riots sustain themselves? 155 Chapter 8 — Riots: the past and the future 177 Bibliography 187 Appendix 215 Word count: 70,193 2 List of tables Table 1: The spaces where riots started 69 Table 2: The places where riots started 70 Table 3: The number of riots happening during normal working hours 73 Table 4: The number of riots which happen during particular calendrical events 73 Table 5: The proportion of non-industrial riots by day of the week 75 Table 6: The likelihood of a given non-industrial riot being on a certain day of the week 75 Table 7: The likelihood of a given riot outside of Glasgow involving prison rescues 98 Table 8: The likelihood of a given riot involving begging or factory visits 111 Table 9: The likelihood of a given riot targeting specific individuals or people in their homes 119 List of figures Figure 1: Angelus Novus (1920) by Paul Klee 16 Figure 2: Geographic spread of rioting in Liverpool 67 Figure 3: Geographic spread of rioting in Manchester 68 Figure 4: Geographic spread of rioting in Glasgow 68 Figure 5: The number of riots per year 78 Figure 6: The number of riots involving prison rescues per year 98 3 Abstract The 19th century is seen by many as a crucial turning point in the history of protest in Britain and across the global north. -

Operation Pastorius WWII

Operation Pastorius WWII Shortly after Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States, just four days after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, he was eager to prove to the United States that it was vulnerable despite its distance from Europe, Hitler ordered a sabotage operation to be mounted against targets inside America. The task fell to the Abwehr (defense) section of the German Military Intelligence Corps headed by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The job was right up the Abwehr’s alley. It already had conducted extensive sabotage operations against the Reich‘s European enemies, developing all the necessary tools and techniques and establishing an elaborate sabotage school in the wooded German countryside near Brandenburg. Lieutenant Walter Kappe, 37, a pudgy, bull-necked man, was given command of the mission against America, which he dubbed Operation Pastorius, after an early German settler in America. Kappe was a longtime member of the Nazi party, and he also knew the United States very well, having lived there for 12 years. To find men suitable for his enterprise, Lieutenant Kappe scoured the records of the Ausland Institute, which had financed thousands of German expatriates’ return from America. Kappe selected 12 whom he thought were energetic, capable and loyal to the German cause. Most were blue-collar workers, and all but two had long been members of the party. Four dropped out of the team almost immediately; the rest were organized into two teams of four. George John Dasch, the eldest at 39, was chosen to lead the first team. He was a glib talker with what Kappe thought were American mannerisms. -

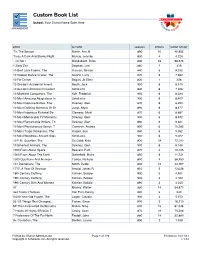

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Erich Gimpel and Colepaugh Case KV 2/564

Reference abstracts of KV 2/564 This document contains materials derived from the latter file Its purpose: to be used as a kind of reference document, containing my personal selection of report sections; considered being of relevance. My input: I have in almost every case created transcripts of the just reproduced file content. However, sometimes adding my personal opinion; always accompanied by: AOB (with- or without brackets) Please do not multiply this document Remember: that the section-copies still do obey to Crown Copyright By Arthur O. Bauer Please notice: For simplicity, I have this time not completely transcribed all genuine text contents, therefore I would like to advise you to read these passages also. This concerns a unique Story, where two spies had been brought ashore on the beach of Frenchman’s Bay in the US State Maine, on 29th November 1944. One was Erich Gimpel the second one was Colepaugh a US born ‘subject’. Erich Gimpel passed finally away in 2010, living Sao Paulo, at an age of 100 years! As to ease to understand the context I first would like to quote from Wikipedia. Quoting from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Gimpel Erich Gimpel From Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia Erich Gimpel (25 March 1910 in Merseburg – 3 September 2010 in Sao Paulo) was a German spy during World War II. Together with William Colepaugh, he traveled to the United States on an espionage mission (operation Elster) in 1944 and was subsequently captured by the FBI in New York City.[1] German secret agent Gimpel had been a radio operator for mining companies in Peru in the 1930s. -

Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 06-04-1897 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-4-1897 Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 06-04-1897 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 06-04-1897." (1897). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ sfnm_news/5635 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL. 34. SANTA FE N. Mm FRIDAY, JUNE 4, 1897. NO. 88 COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES WASHINGTON NEWS BUDGET JUDGE LYNCH'S WORK IN OHIO BONITO & URRACA DISTRICTS The Pioneers In Their Line. Fourth Annual Commencement of the DRUCS A JEWELRY Senator Mantle Asserts That the Wool A Prisoner Taken from the Urbaua, lew Mexico oneite or Agricul- Mineral Section That is Beginning ture anil mechanic Art. Growers Are Not Satisfied with Ohio, Jail and Lynched by a Mob, to Attract Widespread Attention Anions: Men. GEO. W. HICKOX & CO. the Rate? as Proposed by the Alter Having Two Men Killed The commencement exercises of the Mining; Sew Tariff Bill. and Half a Dozen Injured New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts will be held June 6 to IIS DISCOVERY AND ITS DEVELOPMENT -- MANUFACTURERS 07-- by the Militia. A NOTE OF WARNING IS SOUNDED SI lnolusive. The order of exercises will be as follows: On June 6, at A Company of Troops from Springfield Sunday The Porphyry Dikes bo Prominent in 11 o'olook a. -

DISEC Ballistic Missiles

ATSMUN 2018 Forum: Disarmament and International Security Committee Topic: The Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Student Officer: Thomas Antoniou Position: Chair ! ! Page !1 ATSMUN 2018 The Intercontinental Ballistic Missile An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a guided ballistic missile with a minimum range of 5,500 kilometres (3,400 mi) primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Similarly, conventional, chemical, and biological weapons can also be delivered with varying effectiveness, but have never been deployed on ICBMs. Most modern designs support multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), allowing a single missile to carry several warheads, each of which can strike a different target. Early ICBMs had limited precision, which made them suitable for use only against the largest targets, such as cities. They were seen as a “safe” basing option, one that would keep the deterrent force close to home where it would be difficult to attack. Attacks against military targets (especially hardened ones) still demanded the use of a more precise manned bomber. Second- and third-generation designs (such as the LGM-118 Peacekeeper) dramatically improved accuracy to the point where even the smallest point targets can be successfully attacked. ICBMs are differentiated by having greater range and speed than other ballistic missiles: intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs), medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs), short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) and tactical ballistic missiles (TBMs). Short and medium-range ballistic missiles are known collectively as theatre ballistic missiles. The history of the ICBM ! Throughout history several states have attempted to develop nuclear weapons with ballistic capabilities. After the first use of nuclear weapons in 1945 many test were conducted to significantly expand the knowledge about nuclear weapons and their capabilities, The graph above shows all the test conducted by all states with successful nuclear development programs. -

Das Gegenteil Ist Wahr

Argo-Verlag Ingrid Schlotterbeck Sternstraße 3, D-87616 Marktoberdorf Telefon: 0 83 49/92 04 40 Fax: 0 83 49/92 04 449 email: mailemagazin2000plus.de Internet: www.magazin2000plus.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Kein Teil des Werkes, auch Bilder dürfen in irgendeiner Form (Druck, Fotokopie, Mikrofilm, oder in einem anderen Verfahren) ohne schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages reproduziert oder unter Verwendung elektronischer Systeme verarbeitet, vervielfältigt oder verbreitet werden. Copyrightverletzungen jeglicher Art werden gerichtlich verfolgt. 3. Auflage 2011 Satz, Layout, grafische Gestaltung: Argo-Verlag Umschlaggestaltung: Argo-Verlag ISBN: 978-3-9808206-4-6- Copyright © by Argo 2011 Gedruckt in Deutschland auf chlor- und säurefreiem Papier. Johannes Jürgenson Das Gegenteil ist wahr Zweiter Band: Die Wahre Herkunft der Flugscheiben und die Folgen für die Weltpolitik Denkbar ist alles, möglich vieles und plausibel eine ganze Menge. Die entscheidende Frage bleibt jedoch: Was ist wahr? - Geleitwort - Dieses Buch gibt dem Leser Einblicke in Begebenheiten der letzten Jahrzehnte, die dem deutschen Volk bewußt verschwiegen wurden und noch werden. in unserem Zeitalter geschehen Dinge, die für den Verstand des Durchschnittsbürgers und das betrifft uns ja fast alle, unbegreiflich, unfaßbar erscheinen. Wissenschaft und Technik sind soweit vorangeschritten, wie einst in den Zukunftsromanen eines Jules Verne und Hans Dominik, nun die Wende des 19. zum 20. Jahrhunderts beschrieben wurden, sich längst weit darüber hinaus entwickelten. Zum Leidwesen der gesamten Menschheit hat sich eine Clique gewissenloser Menschen zusammen geschlossen, die, die Fäden nicht nur auf dem Gebiet der weltweiten Finanzen ziehen, sondern auch ihr Spinnennetz über die gesamte Wissenschaft, Technik, Medien und Militärs gezogen haben und somit versuchen sich den Rest der Menschheit zu Sklaven zu machen. -

Neoliberal Governance and the Erosion of Local Democracy in the United States and Argentina

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 2017 Lacking Legitimacy: Neoliberal Governance and the Erosion of Local Democracy in the United States and Argentina Adriane Ackerman Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ackerman, Adriane, "Lacking Legitimacy: Neoliberal Governance and the Erosion of Local Democracy in the United States and Argentina" (2017). University Honors Theses. Paper 441. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.438 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Lacking Legitimacy: Neoliberal Governance and the Erosion of Local Democracy in the United States and Argentina By Adriane Aileen Ackerman An undergraduate honors thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Political Science Thesis Advisor: Dr. Richard A. Clucas, PhD Portland State University 2017 ABSTRACT An extension of capitalism’s relentless growth, neoliberal globalization has characterized most of the policies and practices that have proliferated between nation-states since the late 1970’s, producing a “flatter” world in which spheres of influence, both economically and politically, have become inextricably interdependent. Some prominent results of this interdependence include consolidation of wealth, extreme socioeconomic stratification, greater influence of money upon politics, and deepening ideological divide within the populace. Increased sharing of the roles and responsibilities of governing with the private sector, along with increased access to information and exposure to systemic nepotism, have together undermined the sovereignty and preeminence of nation states as the most relevant governmental institutions. -

Michiko Uryu

Another Thanksgiving Dinner: Language, Identity and History in the Age of Globalization by Michiko Uryu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Claire Kramsch, Chair Professor Ingrid Seyer-Ochi Professor Daniel O’Neill Fall 2009 Another Thanksgiving Dinner: Language, Identity and History in the Age of Globalization © 2009 By Michiko Uryu Abstract Another Thanksgiving Dinner: Language, Identity and History in the Age of Globalization by Michiko Uryu Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Claire Kramsch, Chair Intercultural communication is often discussed with reference to the participants’ culturally different knowledge, its impact upon their conversational styles and the accompanying effect on success or failure in communicating across cultures. Contemporary intercultural encounters, however, are more complicated and dynamic in nature since people live in multiple and shifting spaces with accompanying identities while national, cultural, and ideological boundaries are obscured due to the rapid globalization of economy, the accompanying global migration and the recent innovations in global information/communication technologies. Re-conceptualizing the notion of context as conditions for discourse occurrences, this dissertation research aims to explore the social, cultural, ideological and historical dimensions of conversational discourse between participants with multiple and changing identities in an intercultural global context. An ethnographic research was conducted during 2006-2007 in an American non-profit organization founded 50 years ago to foster social and cultural exchanges among female foreign visitors at a prestigious American university in New England, USA. -

By Michiko Uryu a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy I

Another Thanksgiving Dinner: Language, Identity and History in the Age of Globalization by Michiko Uryu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Claire Kramsch, Chair Professor Ingrid Seyer-Ochi Professor Daniel O’Neill Fall 2009 Another Thanksgiving Dinner: Language, Identity and History in the Age of Globalization © 2009 By Michiko Uryu Abstract Another Thanksgiving Dinner: Language, Identity and History in the Age of Globalization by Michiko Uryu Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Claire Kramsch, Chair Intercultural communication is often discussed with reference to the participants’ culturally different knowledge, its impact upon their conversational styles and the accompanying effect on success or failure in communicating across cultures. Contemporary intercultural encounters, however, are more complicated and dynamic in nature since people live in multiple and shifting spaces with accompanying identities while national, cultural, and ideological boundaries are obscured due to the rapid globalization of economy, the accompanying global migration and the recent innovations in global information/communication technologies. Re-conceptualizing the notion of context as conditions for discourse occurrences, this dissertation research aims to explore the social, cultural, ideological and historical dimensions of conversational discourse between participants with multiple and changing identities in an intercultural global context. An ethnographic research was conducted during 2006-2007 in an American non-profit organization founded 50 years ago to foster social and cultural exchanges among female foreign visitors at a prestigious American university in New England, USA.