By Michiko Uryu a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military History Anniversaries 0101 Thru 0131

Military History Anniversaries 1 thru 31 January Events in History over the next 30 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Jan 00 1944 – WW2: USS Scorpion (SS–278). Date of sinking unknown. Most likely a Japanese mine in Yellow or East China Sea. 77 killed. Jan 00 1945 – WW2: USS Swordfish (SS–193) missing. Possibly sunk by Japanese Coast Defense Vessel No. 4 on 5 January or sunk by a mine off Okinawa on 9 January. 89 killed. Jan 01 1942 – WW2: The War Production Board (WPB) ordered the temporary end of all civilian automobile sales leaving dealers with one half million unsold cars. Jan 01 1945 – WW2: In Operation Bodenplatte, German planes attack American forward air bases in Europe. This is the last major offensive of the Luftwaffe. Jan 02 1777 – American Revolution: American forces under the command of George Washington repulsed a British attack at the Battle of the Assunpink Creek near Trenton, New Jersey. Casualties and losses: US 7 to 100 - GB 55 to 365. Jan 02 1791 – Big Bottom massacre (11 killed) in the Ohio Country, marking the beginning of the Northwest Indian War. Jan 02 1904 – Latin America Interventions: U.S. Marines are sent to Santo Domingo to aid the government against rebel forces. Jan 02 1942 – The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) convicts 33 members of a German spy ring headed by Fritz Joubert Duquesne in the largest espionage case in United States history-the Duquesne Spy Ring. Jan 02 1942 – WW2: In the Philippines, the city of Manila and the U.S. -

Military History Anniversaries 1 Thru 15 January

Military History Anniversaries 1 thru 15 January Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Jan 00 1944 – WW2: USS Scorpion (SS–278). Date of sinking unknown. Most likely a Japanese mine in Yellow or East China Sea. 77 killed. Jan 00 1945 – WW2: USS Swordfish (SS–193) missing. Possibly sunk by Japanese Coast Defense Vessel No. 4 on 5 January or sunk by a mine off Okinawa on 9 January. 89 killed. Jan 01 1781 – American Revolution: Mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line – 1,500 soldiers from the Pennsylvania Line (all 11 regiments under General Anthony Wayne’s command) insist that their three-year enlistments are expired, kill three officers in a drunken rage and abandon the Continental Army’s winter camp at Morristown, New Jersey. Jan 01 1883 – Civil War: President Abraham Lincoln signs the final Emancipation Proclamation, which ends slavery in the rebelling states. The proclamation freed all slaves in states that were still in rebellion as of 1 JAN. Jan 01 1915 – WWI: The 15,000-ton British HMS class battleship Formidable is torpedoed by the German submarine U-24 and sinks in the English Channel, killing 547 men. The Formidable was part of the 5th Battle Squadron unit serving with the Channel Fleet. Jan 01 1942 – WW2: The War Production Board (WPB) ordered the temporary end of all civilian automobile sales leaving dealers with one half million unsold cars. Jan 01 1942 – WW2: United Nations – President Franklin D. -

Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War

Author’s Accepted Manuscript Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War Matthew Bradley, Matthew Nealiegh, John Oh, Philip Rothberg, Eric Elster, Norman Rich www.elsevier.com/locate/cpsurg PII: S0011-3840(16)30157-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.004 Reference: YMSG552 To appear in: Current Problems in Surgery Cite this article as: Matthew Bradley, Matthew Nealiegh, John Oh, Philip Rothberg, Eric Elster and Norman Rich, Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War, Current Problems in Surgery, http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.004 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. COMBAT CASUALTY CARE AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE LAST 100 YEARS OF WAR Matthew Bradley, M.D. 1, 2, Matthew Nealiegh, M.D. 1, John Oh, M.D. 1, Philip Rothberg, M.D. 1, Eric Elster M.D. 1, 2, Norman Rich M.D. 1 1 Department of Surgery, Uniformed Services University -Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Wisconsin Ave., Bethesda, MD 20889 2Naval Medical Research Center, 503 Robert Grant Ave., Silver Spring, MD 20910 Corresponding Author: Matthew J. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 2 Chapter 1, CI in World

CI in World War II 113 CHAPTER 1 Counterintelligence In World War II Introduction President Franklin Roosevelts confidential directive, issued on 26 June 1939, established lines of responsibility for domestic counterintelligence, but failed to clearly define areas of accountability for overseas counterintelligence operations" The pressing need for a decision in this field grew more evident in the early months of 1940" This resulted in consultations between the President, FBI Director J" Edgar Hoover, Director of Army Intelligence Sherman Miles, Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral W"S" Anderson, and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A" Berle" Following these discussions, Berle issued a report, which expressed the Presidents wish that the FBI assume the responsibility for foreign intelligence matters in the Western Hemisphere, with the existing military and naval intelligence branches covering the rest of the world as the necessity arose" With this decision of authority, the three agencies worked out the details of an agreement, which, roughly, charged the Navy with the responsibility for intelligence coverage in the Pacific" The Army was entrusted with the coverage in Europe, Africa, and the Canal Zone" The FBI was given the responsibility for the Western Hemisphere, including Canada and Central and South America, except Panama" The meetings in this formative period led to a proposal for the organization within the FBI of a Special Intelligence Service (SIS) for overseas operations" Agreement was reached that the SIS would act -

Tsetusuo Wakabayashi, Revealed

Tsetusuo Wakabayashi, Revealed By Dwight R. Rider Edited by Eric DeLaBarre Preface Most great works of art begin with an objective in mind; this is not one of them. What follows in the pages below had its genesis in a research effort to determine what, if anything the Japanese General Staff knew of the Manhattan Project and the threat of atomic weapons, in the years before the detonation of an atomic bomb over Hiroshima in August 1945. That project drew out of an intense research effort into Japan’s weapons of mass destruction programs stretching back more than two decades; a project that remains on-going. Unlike a work of art, this paper is actually the result of an epiphany; a sudden realization that allows a problem, in this case the Japanese atomic energy and weapons program of World War II, to be understood from a different perspective. There is nothing in this paper that is not readily accessible to the general public; no access to secret documents, unreported interviews or hidden diaries only recently discovered. The information used in this paper has been, for the most part, available to researchers for nearly 30 years but only rarely reviewed. The paper that follows is simply a narrative of a realization drawn from intense research into the subject. The discoveries revealed herein are the consequence of a closer reading of that information. Other papers will follow. In October of 1946, a young journalist only recently discharged from the US Army in the drawdown following World War II, wrote an article for the Atlanta Constitution, the premier newspaper of the American south. -

Rioting and Time

Rioting and time Collective violence in Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow, 1800-1939 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Matteo Tiratelli School of Social Sciences 1 Table of contents Abstract 4 Declaration & Copyright 5 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter 1 — Rioting and time 7 Chapter 2 — Don’t call it a riot 24 Chapter 3 — Finding riots and describing them 42 Chapter 4 — Riots in space, time and society 64 Chapter 5 — The changing practice of rioting 102 Chapter 6 — The career of a riot: triggers and causes 132 Chapter 7 — How do riots sustain themselves? 155 Chapter 8 — Riots: the past and the future 177 Bibliography 187 Appendix 215 Word count: 70,193 2 List of tables Table 1: The spaces where riots started 69 Table 2: The places where riots started 70 Table 3: The number of riots happening during normal working hours 73 Table 4: The number of riots which happen during particular calendrical events 73 Table 5: The proportion of non-industrial riots by day of the week 75 Table 6: The likelihood of a given non-industrial riot being on a certain day of the week 75 Table 7: The likelihood of a given riot outside of Glasgow involving prison rescues 98 Table 8: The likelihood of a given riot involving begging or factory visits 111 Table 9: The likelihood of a given riot targeting specific individuals or people in their homes 119 List of figures Figure 1: Angelus Novus (1920) by Paul Klee 16 Figure 2: Geographic spread of rioting in Liverpool 67 Figure 3: Geographic spread of rioting in Manchester 68 Figure 4: Geographic spread of rioting in Glasgow 68 Figure 5: The number of riots per year 78 Figure 6: The number of riots involving prison rescues per year 98 3 Abstract The 19th century is seen by many as a crucial turning point in the history of protest in Britain and across the global north. -

International Spy Museum

International Spy Museum Searchable Master Script, includes all sections and areas Area Location, ID, Description Labels, captions, and other explanatory text Area 1 – Museum Lobby M1.0.0.0 ΚΑΤΆΣΚΟΠΟΣ SPY SPION SPIJUN İSPİYON SZPIEG SPIA SPION ESPION ESPÍA ШПИОН Language of Espionage, printed on SCHPION MAJASUSI windows around entrance doors P1.1.0.0 Visitor Mission Statement For Your Eyes Only For Your Eyes Only Entry beyond this point is on a need-to-know basis. Who needs to know? All who would understand the world. All who would glimpse the unseen hands that touch our lives. You will learn the secrets of tradecraft – the tools and techniques that influence battles and sway governments. You will uncover extraordinary stories hidden behind the headlines. You will meet men and women living by their wits, lurking in the shadows of world affairs. More important, however, are the people you will not meet. The most successful spies are the unknown spies who remain undetected. Our task is to judge their craft, not their politics – their skill, not their loyalty. Our mission is to understand these daring professionals and their fallen comrades, to recognize their ingenuity and imagination. Our goal is to see past their maze of mirrors and deception to understand their world of intrigue. Intelligence facts written on glass How old is spying? First record of spying: 1800 BC, clay tablet from Hammurabi regarding his spies. panel on left side of lobby First manual on spy tactics written: Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. 6 video screens behind glass panel with facts and images. -

Operation Pastorius WWII

Operation Pastorius WWII Shortly after Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States, just four days after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, he was eager to prove to the United States that it was vulnerable despite its distance from Europe, Hitler ordered a sabotage operation to be mounted against targets inside America. The task fell to the Abwehr (defense) section of the German Military Intelligence Corps headed by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The job was right up the Abwehr’s alley. It already had conducted extensive sabotage operations against the Reich‘s European enemies, developing all the necessary tools and techniques and establishing an elaborate sabotage school in the wooded German countryside near Brandenburg. Lieutenant Walter Kappe, 37, a pudgy, bull-necked man, was given command of the mission against America, which he dubbed Operation Pastorius, after an early German settler in America. Kappe was a longtime member of the Nazi party, and he also knew the United States very well, having lived there for 12 years. To find men suitable for his enterprise, Lieutenant Kappe scoured the records of the Ausland Institute, which had financed thousands of German expatriates’ return from America. Kappe selected 12 whom he thought were energetic, capable and loyal to the German cause. Most were blue-collar workers, and all but two had long been members of the party. Four dropped out of the team almost immediately; the rest were organized into two teams of four. George John Dasch, the eldest at 39, was chosen to lead the first team. He was a glib talker with what Kappe thought were American mannerisms. -

Risk of Public Disclosure: Learning from Willy Wonka

Issue 20, 16 December 2014 WhiteNews Global corporate espionage news Editorial: WhiteRock Updates: All About Privacy 2 Threat: Are LinkedIn Contacts Trade Secrets? 3 News: $400 Bn Military Espionage; Code Fishing 4 News: Falcani Black List; Football Whistleblower 5 Feature: Willy Wonka’s Lessons in Espionage 6-7 Technology: Hearing Aid for Corporate Spies 8-9 Extra: FBI’s Untold Story; Spy on Your Rival 10-11 Letter From America: Spying Breakfast Club 12 Exclusive Reporting for WhiteRock’s Clients Risk of Public Disclosure: Learning from Willy Wonka Our feature story is seemingly seasonal and light-hearted, but the film ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ carries a very strong espionage message that is relevant even 50 years later. Willy Wonka was a brilliant CEO who knew that the only person who could protect his trade was himself. Wonka’s story translates superbly into today’s corporate world, and in this issue we are discussing how the contemporary big players are maintaining their edge and success over their competitors. This is equally relevant for small and medium-sized businesses, who really don’t prioritise their trade secrets, making their advantage extremely vulnerable. In the technology section we analyse the delicate matter of hearing aid systems. They’re everywhere, including in corporate meeting rooms, and nobody really considers these as a threat. We’re examining how to achieve a balance between protecting valuable corporate information without creating an embarrassing situation that in turn could lead to reputational damage! Our extra section may give you a wrong impression this time. No, we’re not teaching you how to spy, this is not our bag. -

Sojourner Adjustment : a Diary Study

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1992 Sojourner Adjustment : A Diary Study Susan Elizabeth Hemstreet Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hemstreet, Susan Elizabeth, "Sojourner Adjustment : A Diary Study" (1992). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4377. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6261 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Susan Elizabeth Hemstreet for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages presented January 21, 1992. Title: Sojourner Adjustment: A Diary Study. APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Maqone ~. Terdal, Chair Suwako Watanabe The focus of the ethnographic diary study is introduced and contextualized in the opening chapter with a site description. The thesis examines the diaries written during a sojourn of over two years in Japan . and proposes to answer the question, "How did the sojourner's initial maladjustment subsequently develop into satisfactory adjustment?" 2 The literature on diary studies, culture shock and sojourner adjustment is reviewed in order to establish standards of the diary study genre and a framework from which to analyze the diary. Using the qualitative methods of a diary study, salient themes of the adjustment are examined. The diarist's progression through the adjustment stages as proposed by the literature is supported, and the coping strategies of escapism, reaching out to people, writing, positive thinking, religious beliefs, compulsive behaviors, goal-setting and seeing the experience as finite are discussed in depth. -

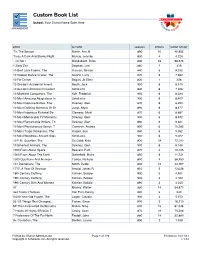

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Secret Operations of World War II. by Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 11 Number 4 Article 6 Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. Millard E. Moon U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 89-93 Recommended Citation Moon, Millard E.. "Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018.." Journal of Strategic Security 11, no. 4 (2019) : 89-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.11.4.1717 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol11/iss4/6 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol11/iss4/6 Moon: Book Review: <i>Secret Operations of World War II</i> Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. ISBN 978-1- 78274-632-4. Photographs. Bibliography. Index. Pp. 224. $21.77. The author has done an excellent job of providing an overview of the most prominent secret operations, and the exploits of some of the most heroic, but little known, agents operating for the Allied forces in World War II.